Wellness in residency: Addressing the neglected need in lower middle-income countries

Abstract

The concept of wellness incorporates many domains, including mental, physical, social, and integrated well-being. However, it is not well understood in most lower middle-income countries (LMIC). The significance of practicing wellness during residency, focusing on the context of LMIC, is described here. Based on the authors’ experiences of working in LMIC, the challenges faced during residency and the importance of prioritizing self-care and well-being is highlighted. Physician burnout is a global concern having a negative impact on patient care quality, patient satisfaction, and professionalism. Interventions to address wellness can be individual and organization-based. Individual interventions include mindfulness training, behavioral interventions, self-care practices, and support networks. Organizational interventions involve the establishment of wellness committees, introduction of wellness curricula, optimization of workflows, and creation of shared social spaces. There is a need for implementing wellness practices within residency programs in LMIC. By focusing on wellness, physicians can mitigate burnout, enhance their well-being, and improve patient care outcomes.

1Introduction

Wellness is not a new concept. An article titled “Health of Residents,” published in The Hospital in 1907, emphasized the importance of taking time for oneself during residency, good sleep and taking time to enjoy leisure activities [1]. The authors concluded that, “We have now outlined the house surgeon’s duty towards himself, and we would conclude by reminding him that without due attention to his own health, he will sooner or later be unable to perform his duty towards his patients” [1]. Fast forward to 2023, and residency programs in many parts of the world are still struggling to inculcate wellness during residency, resulting in increased prevalence of burnout in low and lower middle income countries (LIC/LMIC) [2].

In a survey conducted by Malik et al. among residents of public hospitals of Pakistan, 57.9% of the residents reported burnout [2]. It was alarming that only 5% of residents with burnout sought professional help to deal with this issue [2]. Moradi et al., in a systematic review, documented that 44% of residents of obstetrics and gynecology had burnout [3], and Ogboghodo et al. reported 41.7% of residents in Nigeria had burnout [4]. It is interesting to note that, while all these studies point out the prevalence of burnout, none commented on the practice of wellness to combat burnout [2–4].

MTK (the lead author), a third year resident in a Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation program in Pakistan, shared his experience of residency as follows:

“I joined the specialty of my choice three years back. I got the specialty that I love, the specialty in which I could see myself evolving and spending the rest of my life in. It was ‘Love at first sight’. I was a motivated person, with the belief that I could face all the troubles of residency with firmness and dedication towards my goal. I was soon to be proven wrong. Three years in, I have suffered through two nights where I was about to harm myself, had multiple episodes of panic attacks, several crying sessions in the hospital parking lot, lost my dream team with which I initially thought to keep forever in touch and work to advance our specialty. I was not this person before my residency.

Residency is challenging. I was well aware of the challenges that I might face during my residency, but I had not appropriately judged the value of practicing wellness while I was daily exposed to various types of physical, mental, emotional and social challenges. During residency training, we spend most of our time in hospital, struggle to get decent sleep of six hours and try to juggle time for our family and friends. It is easy to forget oneself in all this.”

While wellness is not a new concept, it is not widely implemented in residency programs in LMIC. The residency and fellowship programs in Pakistan are not bound to address wellness as part of program requirements in residency. However, in higher income countries like America, burnout is assessed and institutions are required to provide resources to address wellness as an employee benefit [5]. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education addresses wellness as part of program requirements for residency and fellowship training programs [5]. The aim of this manuscript is to define wellness, describe its domains and highlight some of the interventions that are available in the literature to implement wellness in residency programs in LMIC.

2Definition

In a recent systematic review by Brady et al., only 11 out of a total of 78 included studies explicitly defined wellness [6]. This presents a challenge. How can a concept be practiced without clearly defining its domains? Brady et al. defined physician wellness as “a multifaceted construct that includes mental, physical, social, and spiritual QOL in both physicians’ work and personal lives … physician wellness includes the absence of distress and the presence of positive well-being, including vigor and thriving behaviors, beyond mere job satisfaction” in which QOL is defined as quality of life (bolding added for emphasis) [6]. Cherak et al. defined wellness as “a general sense of personal well-being - the opportunity to be and to do what is perceived by the learner as most needed and most valued” [7].

3Importance of wellness

Lack of physician wellness is a global phenomenon [6]. According to some estimates, 20-50% of physicians report ‘burnout,’ which is a negative wellness indicator in physicians [6]. Burnout is characterized as a triad of physician exhaustion, depersonalization, and low sense of personal accomplishment [8]. Physician burnout affects patients’ quality of care, increases the risk for patient-related safety incidents, reduces patient satisfaction, and leads to low professionalism among doctors [9]. From 2010 to 2019, suicide-related deaths were reported among 105 residents and 126 physicians [10]. Female residents had a higher risk of suicide-related deaths [10]. In the United states, approximately 119 physician suicides occur annually [11]. It is important to improve physician wellness to mitigate physician burnout [9].

4Domains of wellness

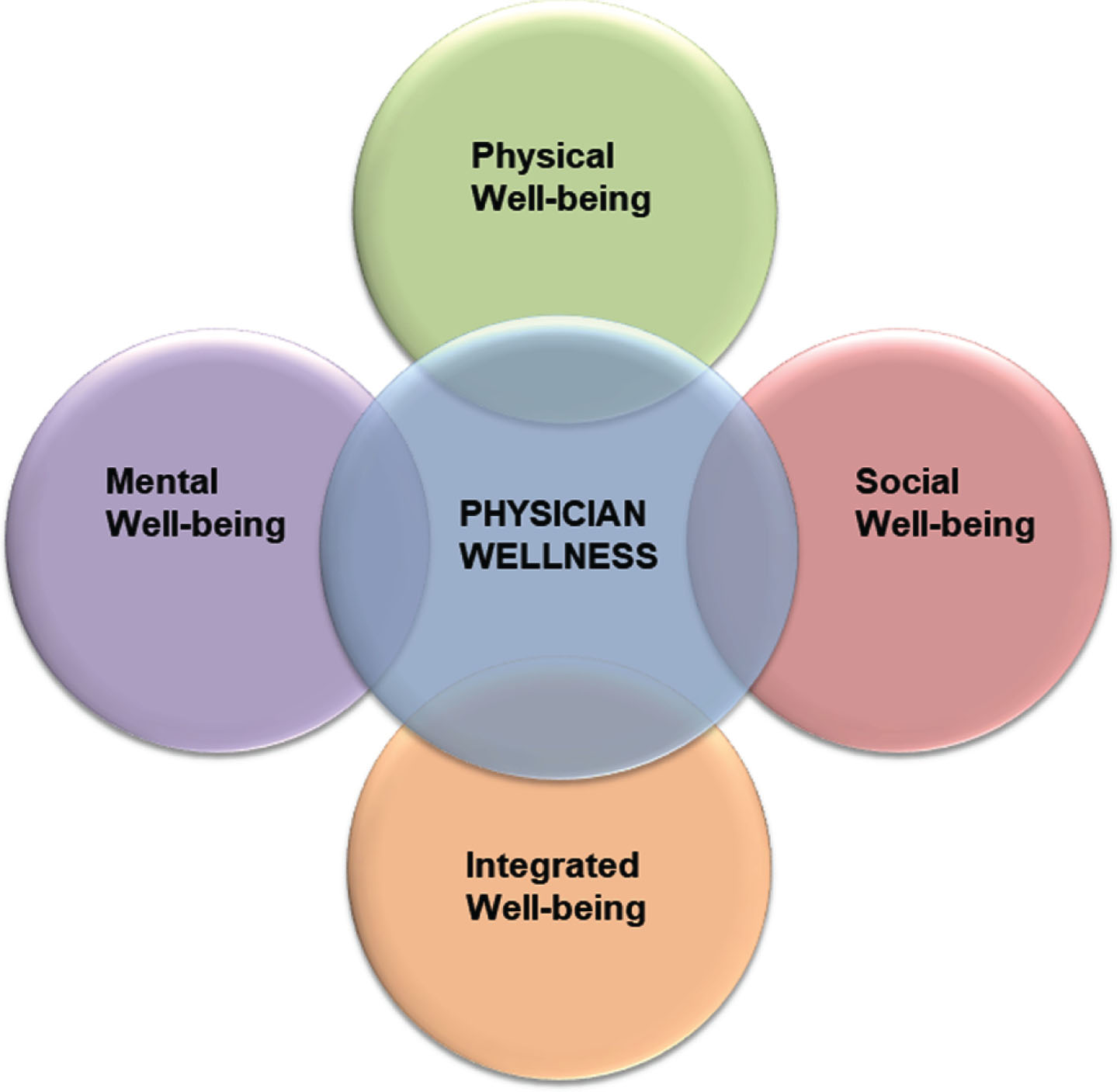

Wellness has been divided into four domains (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1

Domains of wellness.

i. Mental well-being: Mental well-being allows a physician to realize and accept their own potential, develop coping strategies to deal with stressors, develop resilience, have a healthy emotional and intellectual QOL, have a stable global affective state, have career satisfaction and remain committed to their profession [6, 7].

ii. Physical well-being: Physical well-being requires that a physician maintain a healthy work-life balance, maintain an optimal level of activity with respect to their age, practice self-care, focus on nutrition, enjoy good quality sleep, practice leisure activities that bring joy, and not be constantly fatigued [6, 7].

iii. Social well-being: This focuses on the physician as an individual who is accepted in their social circle and among colleagues, and who can express their feelings, needs, identities and opinions to their colleagues [7]. A physician with social well-being cares for their patients, enjoys rewarding patient interactions, and has healthy interpersonal relationships, peer support, and coping mechanisms [6]. Healthy coping strategies to address isolation, depersonalization and absence of equity are identified [6].

iv. Integrated well-being: This encompasses the eudemonistic well-being of an individual [6]. A physician with integrated well-being enjoys a deeper meaning from their life and work, has satisfaction with their work/life balance or integration, and has healthy spiritual and overall QOL [6].

5Interventions for wellness

Interventions for wellness can be categorized into individual and organization based interventions that are directed towards incorporating the culture of wellness among residents. The following evidence-based interventions for wellness are being implemented in higher income countries, but these can be implemented in LMIC as well, owing to their universal nature.

5.1Individual interventions

i. Mindfulness training should be included in residency to improve wellness and decrease burnout (Level 1b, Grade B). Mindfulness enables a person to become aware of the present situation by accepting their emotions, thoughts and physical sensations [12]. A session of mindfulness meditation for 10-20 minutes daily for 30 days has been shown to decrease stress and burnout [12]. Practicing mindfulness through journaling, narrative medicine, and reflective questioning also reduces burnout rates [12].

ii. Behavioral interventions like cognitive reframing as well as empathy and self-compassion improve wellness (Level 4, Grade C) [12]. The importance of self-care and self-compassion to combat burnout cannot be overemphasized.

iii. Self-care intervention results in lower rates of burnout [12]. It becomes challenging to schedule self-care activities during residency; however effective behavioral change plans can be taught to residents [12]. Self-care interventions include disciplines such as exercise, nutrition, sleep, personal hygiene, and emotional health [12].

iv. Having a strong support network either within or outside the work environment is associated with reduced burnout rates [12]. A support network can be a friend, colleague or a trained professional designated by peers or faculty [12].

5.2Organization-based interventions

i. Wellness committee: A wellness committee consisting of residents and faculty can be created at departmental and institutional levels to frequently assess resident wellness and ensure provision of opportunities and facilities for residents to practice wellness [12]. The creation of a safe culture of one-on-one meetings with residents should be promoted [12]. A wellness committee can actively identify residents/trainees at risk and provide ways to address and mitigate burnout, rather than waiting for them to ask for help, by which time it may be too late.

ii. Wellness curriculum: It is important to introduce a wellness curriculum during residency [12]. The curriculum should aim to promote activities of physical, mental and social wellness [12]. Residents should be taught stress management, the concept of integrating work and life, coping skills, and management of finances. A residency wellness program can include active and passive interventions [12]. Active interventions include providing workshops, outings, small group activities, and gym access, whereas passive interventions include provision of safe spaces, lectures, and resources for wellness [12].

iii. Workplace/Workflow interventions: Studies have shown that optimization of electronic/manual health records of patients and improving communication between staff and health care providers can optimize residents’ wellness [12]. Additional responsibilities can be offloaded from residents by delegating administrative tasks to non-clinical staff and by ensuring that all members of the medical team including the nursing and allied health care staff are performing their duties efficiently [12]. Optimization of workflows by abovementioned interventions can improve residents’ wellness and decrease burnout [12].

iv. Optimization of resident schedule: Residents working greater than 80 hours per week are at risk to develop burnout [12]. Optimization of work hours and implementation of protected sleep during night calls reduces fatigue and prevents burnout [12]. Providing some degree of control over their schedule enables residents to take some time for themselves and their family [12].

v. Shared social spaces: Shared social places like doctors’ cafeterias, residents’ lounges and libraries can promote wellness; however the ubiquity of these types of places is declining [13]. Shared social spaces foster feelings of connectedness, belonging, and teamwork among physicians [13]. These spaces provide a safe place for reflection and an opportunity to discuss informal clinical care plans of patients with colleagues [7, 13].

For a residency program in LMIC trying to implement wellness initiatives, individual interventions like self-care and mindfulness should be prioritized. These interventions are financially resource-savvy, and residents can be taught to practice these interventions via workshops or group discussions. Out of the organizational interventions mentioned, optimization of workflows, residents’ schedules, and creation of wellness committees may be prioritized. The set of interventions mentioned above may be implemented as is, or may serve as a framework for residency programs in LMIC to implement wellness interventions as per their own requirements. These interventions can serve as a starting point for residency programs in LMIC.

6Barriers for implementation of wellness programs

Addressing physician wellness in LMIC faces various challenges, and it is essential to recognize and overcome these barriers to promote a healthier work environment for residents.

i. Stigma around mental health: Mental health remains stigmatized in many LMIC, discouraging residents from seeking appropriate care and support for their well-being. Overcoming this stigma is crucial to ensuring that residents can openly discuss and address their mental health needs without fear of judgment or discrimination.

ii. Lack of support from regulatory authorities: Post-graduate regulatory authorities and government bodies in LMIC often do not prioritize physician wellness as an integral part of residency training. The lack of motivation to include physician wellness as an employee benefit hinders the development of comprehensive wellness programs.

iii. Financial constraints: The majority of hospitals in LMIC operate with limited financial resources, leading to reluctance to allocate funds for the promotion of physician wellness initiatives. However, investing in wellness programs can ultimately lead to improved patient care and enhanced job satisfaction among residents.

iv. Resistance from senior faculty members: Some senior faculty members may hold the belief that enduring a challenging and demanding residency is necessary to becoming better physicians. This perspective perpetuates a grueling atmosphere, hindering the adoption of more supportive and nurturing environments for residents.

v. Cultural expectations and prioritization of patient care: Within the healthcare culture of many LMIC, there is an ingrained notion that physicians should prioritize patient care above their own well-being. This cultural expectation can lead to a reluctance by hospital administration and policymakers to recognize the detrimental impact of unwell physicians on healthcare systems.

Overcoming these barriers requires a collaborative effort from various stakeholders, including medical institutions, regulatory bodies, government authorities, and senior faculty members. Initiatives aimed at destigmatizing mental health, advocating for the inclusion of physician wellness in residency training, and allocating adequate resources for wellness programs are crucial steps to ensure the well-being and resilience of residents in LMIC. Moreover, fostering a cultural shift that emphasizes the importance of physician well-being and acknowledges the link between healthy physicians and improved patient care will create a more supportive and thriving environment for healthcare professionals. By addressing these barriers, LMIC can move towards fostering a culture of wellness in residency, ultimately benefiting the overall health system and the communities they serve.

7Conclusion

The incorporation of wellness practices into residency programs within LMIC is of paramount importance. Implementing individual-centered interventions such as practicing self-care, mindfulness, and fostering a supportive network can significantly enhance wellness, even in resource-constrained settings. Prioritizing wellness not only helps physicians combat burnout but also uplifts their overall well-being, leading to improved patient care outcomes. Within advocacy for the advancement of medical education and training, it is imperative to underscore the integral role of wellness in nurturing resilient, compassionate, and effective healthcare professionals. By fostering a culture of wellness, LMIC can empower their resident physicians to thrive, thereby fortifying the foundation of their healthcare systems and ensuring the delivery of optimal care to their communities.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical considerations

This study, as a commentary, is exempt from Institutional Review board approval.

Funding

None.

References

[1] | Health of Residents. Hospital (Lond 1886). (1907) ;42: (1076):101–102. |

[2] | Malik AA , Bhatti S , Shafiq A , et al. Burnout among surgical residents in a lower-middle income country – Are we any different? Ann Med Surg (Lond). (2016) ;9: :28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.05.012. |

[3] | Moradi Y , Baradaran HR , Yazdandoost M , Atrak S , Kashanian M Prevalence of Burnout in residents of obstetrics and gynecology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med J Islam Repub Iran. (2015) ;29: (4):235. |

[4] | Ogboghodo EO , Edema OM Assessment of burnout amongst resident doctors in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. (2020) ;3:215–223. doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_37_20. |

[5] | Common program requirements (residency). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; (2022) [cited 2023 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_v3.pdf |

[6] | Brady KJS , Trockel MT , Khan CT , et al. What Do We Mean by Physician Wellness? A Systematic Review of Its Definition and Measurement. Acad Psychiatry. (2018) ;42: (1):94–108. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0781-6. |

[7] | Cherak SJ , Rosgen BK , Geddes A , et al. Wellness in medical education: definition and five domains for wellness among medical learners during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Med Educ Online. (2021) ;26: (1):1917488. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2021.1917488. |

[8] | Parsons M , Bailitz J , Chung AS , et al. Evidence-Based Interventions that Promote Resident Wellness from the Council of Emergency Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. (2020) ;21: (2):412–422. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.11.42961. |

[9] | Hodkinson A , Zhou A , Johnson J , et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2022) ;378: :e070442. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070442. |

[10] | Chahal S , Nadda A , Govil N , et al. Suicide deaths among medical students, residents and physicians in India spanning a decade -An exploratory study using on line news portals and Google database. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2022) ;68: (4):718–728. doi: 10.1177/00207640211011365. |

[11] | Gold KJ , Schwenk TL , Sen A Physician Suicide in the United States: Updated Estimates from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Psychol Health Med. (2022) ;27: (7):1563–1575. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1903053. |

[12] | Parsons M , Bailitz J , Chung AS , et al. Evidence-Based Interventions that Promote Resident Wellness from the Council of Emergency Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. (2020) ;21: (2):412–422. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.11.42961. |

[13] | Uys C , Carrieri D , Mattick K The impact of shared social spaces on the wellness and learning of junior doctors: A scoping review. Med Educ. (2023) ;57: (4):315–330. doi: 10.1111/medu.14946. |