Multisystem inflammatory syndrome with persistent neutropenia in neonate exposed to SARS-CoV-2 virus: A case report and review of literature

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is a postinfectious immune mediated hyperinflammatory state seen in children and adolescent below 21 year of age and develop after 4–6 weeks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus -2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, however, it is rare in neonates. We report an extremely rare and first of its kind case of MIS-C in a neonate with persistent neutropenia.

CASE DESCRIPTION:

A 19-day old boy presented with complaints of fever and loose stools for 1 day and developed rash after admission. Baby was investigated for sepsis and commenced on IV antibiotics empirically. In view of persistent fever, diarrhoea, rash and absence of obvious microbial etiology of inflammation, with elevated inflammatory marker and an epidemiologic link to SARS-CoV-2 infection, the diagnosis of MIS-C-was made. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) was administered and defervescence occurred within 24 hours. He also developed neutropenia during course of illness which persisted on follow up.

CONCLUSION:

MIS-C in neonates is uncommon and fever with elevated inflammatory markers during COVID-19 pandemic should alert the pediatrician to the possibility of MIS-C. Neutropenia may be associated with MIS-C in neonates and warrants prolonged follow up.

1Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) spread all over the word in later half of 2019 and World health organisation declared it pandemic on 11th March 2020 [1]. COVID 19 is a pandora box of clinical manifestations. It usually starts with upper respiratory tract infections and then involves various other systems like gastrointestinal system, cardiovascular system, renal system etc. [2]. Children accounts for a small proportion of SARS-CoV-2 cases, and it is even less common in neonates [3, 4]. National Neonatology Forum INDIA Covid Registry showed 8%perinatal transmission and 1.5%horizontal transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in neonates [4]. MIS is a postinfectious immune mediated hyperinflammatory state due to SARS-CoV-2 virus. There are several case reports and case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) which usually develop after SARS-CoV-2 infection but data regarding the same in neonates is scanty [5, 6]. To our knowledge, this is only third case report of MIS -C in neonates [7, 8].

2Case report

We report a case of 19 days old male neonate presented in our emergency department with complaints of fever and loose stools for 1 day. There was no history of cough, decreased oral intake, difficulty in respiration or abnormal movements. He was born to a 36-year-old second gravida mother at 39 weeks of gestation by LSCS. Mother had pregnancy induced hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus on metformin. Mother had an episode of upper respiratory tract infection 1 weeks before her delivery. Baby cried soon after birth with birth weight of 3.25 kg and discharged with his mother 3 days after his birth. Baby was on exclusive breast feeds and remain asymptomatic till day 17 of life.

On day 18 of life baby developed high grade fever with loose stools 15–16 times. At time of admission (Day 19) baby had fever (axillary temperature of 38.4 degree Celsius). He was normotensive (Mean blood pressure 58 mmHg) and did not have respiratory distress, SPO2 was 96%in room air. There was no gross congenital malformation with normal cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological examination. Baby was investigated for sepsis with complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), blood culture, urine culture and commenced on full feeds and IV antibiotics empirically for suspected sepsis. Chest x-ray showed clear lung fields. Blood gas analysis was unremarkable. Chip based RTPCR test of baby for SARS-CoV-2 was negative at the time of admission while Mother of baby tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic) and was isolated at home. Father of the baby tested negative. Mother had history of fever for 2–3 days, 1 week before delivery, however she was not tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Baby’s aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), blood urea and serum creatinine were within normal limit. C-reactive protein (CRP) was 12.13 mg/dl (reference range 0.08–1.12 mg/dl). Baby had hyponatremia (serum sodium-127 meq/L), hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin-2.92 gm/dl). Fever spike persisted for next 48hr despite being on antibiotics and round the clock paracetamol. Urine routine & microscopy was unremarkable and cerebrospinal fluid examination was normal. Blood and urine culture were sterile. Laboratory parameters of the index case are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Laboratory parameters of the neonate

| Laboratory parameters | 03/06/21 | 05/06/21 | 07/06/21 | 12/06/21 | 15/07/21 |

| Hb(gm/dl) | 15.5 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 14.0 | 12.9 |

| TLC (per cmm) | 11800 | 8600 | 8900 | 11200 | 8200 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 65 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 22 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 32 | 66 | 69 | 70 | 70 |

| Platelet Count (Per cmm) | 97000 | 443000 | 429000 | 524000 | 450000 |

| Blood culture | Sterile | ||||

| Urine routine/micro | Normal | ||||

| Urine culture | Sterile | ||||

| CSF Cells | 7 (100%Lymhocytes) | ||||

| CSF Protein (mg/dl) | 55.9 | ||||

| CSF Sugar (mg/dl) | 40 | ||||

| CSF Culture | Sterile | ||||

| Serum Sodium (meq/L) | 127 | ||||

| Serum Potassium (meq/L) | 5 | ||||

| SGOT/SGPT (U/L) | 64/36 | ||||

| Serum Albumin (gm/dl) | 2.92 |

CSF (Cerebrospinal fluid), SGOT (Serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase), SGPT (Serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase), TLC (Total leukocyte coun.

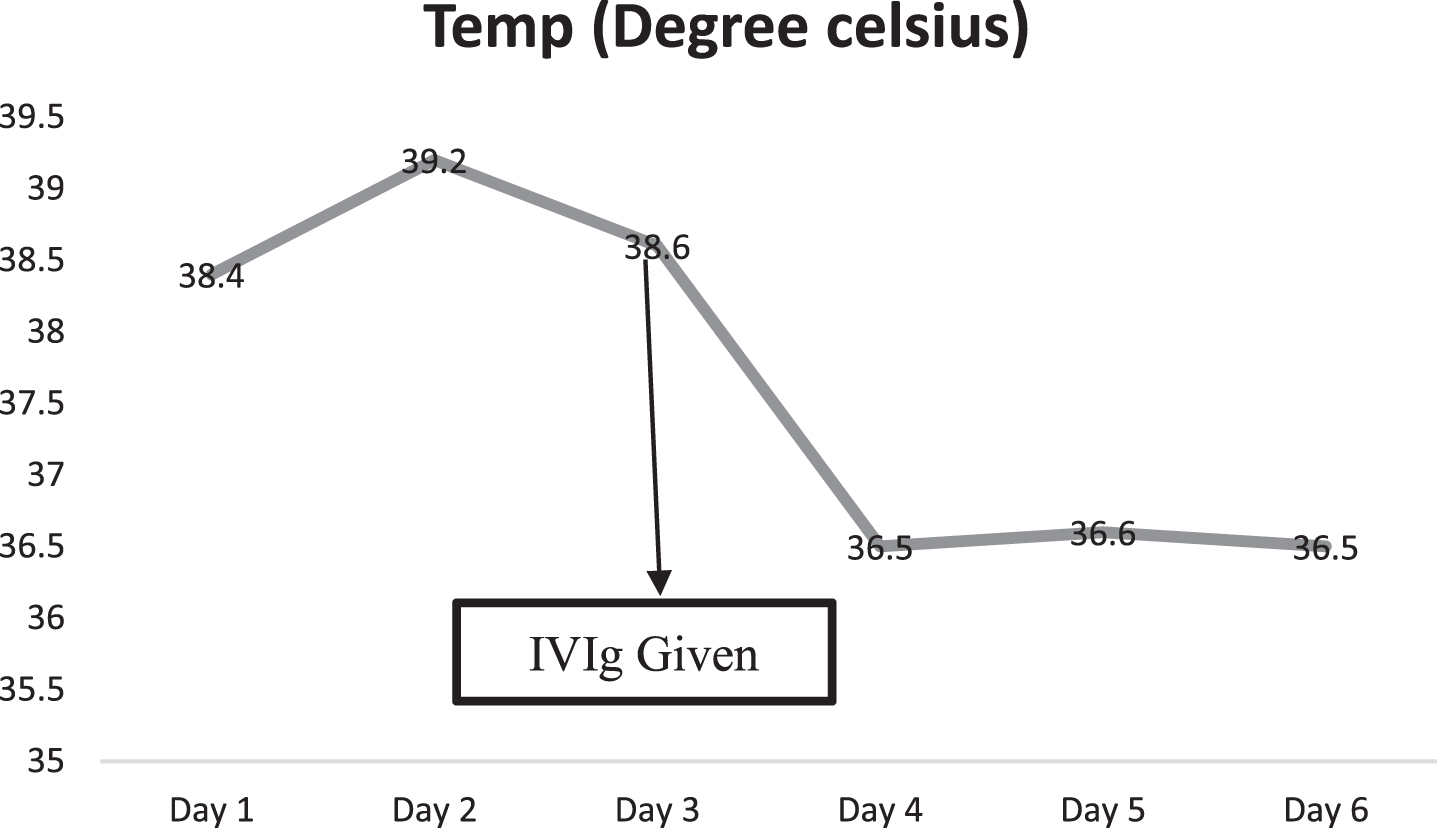

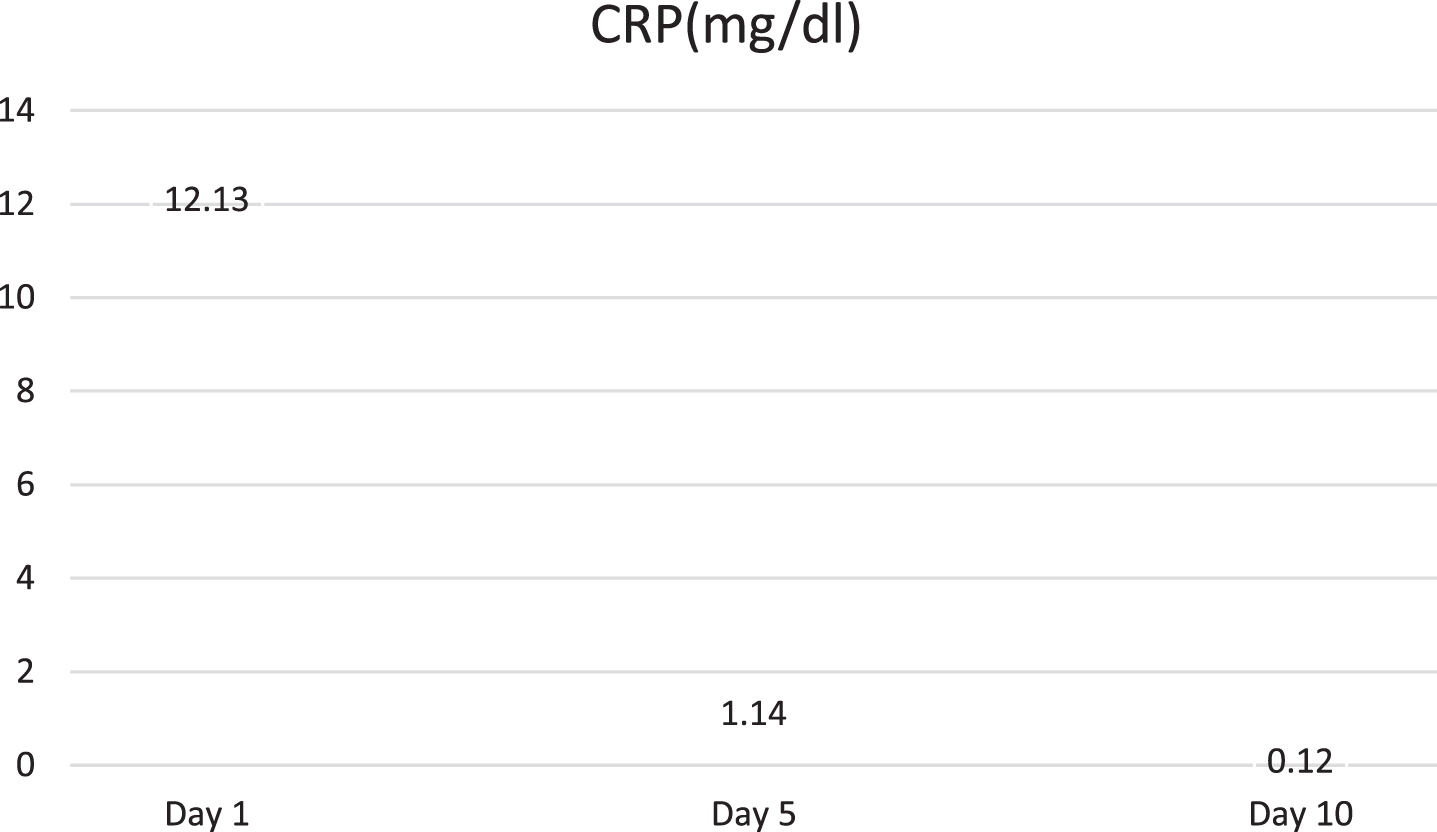

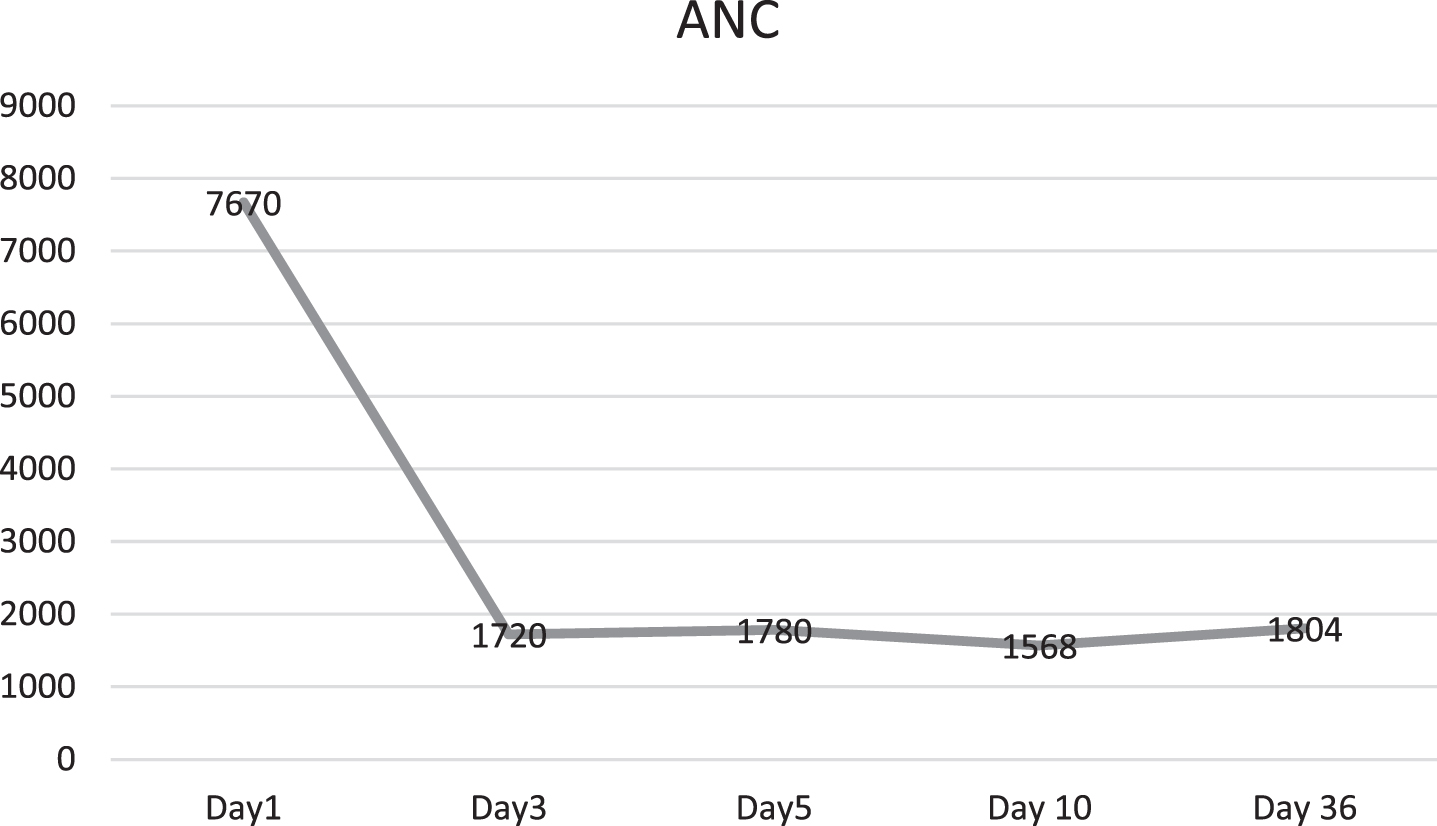

Baby developed rash over forehead and cheeks on day 2 of admission (Fig. 1). At this point, in view of persistent fever without a focus with high CRP, MIS-C-neonatal was suspected and worked up for the same. Echocardiography showed normal structure and function of heart (70%ejection fraction) with normal coronary arteries. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm. SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody titre was 1.47(reactive≥1.0 S/Co, signal to cut off ratio, SARS-CoV-2 IgG,). Serum ferritin, D-dimer and interleukin-6 were 710.30 ng/ml (reference range 25–300 ng/ml), 1620 ng/ml (reference range 0–500 ng/ml) and 1624 pg/ml (normal value 0.5–6.4 pg/ml) respectively. CBC did not show lymphopenia. Incidentally absolute neutrophil count (ANC) showed decreasing trend (7670/cmm at admission, subsequent ANC were 1720/cmm and 1768/cmm). In view of persistent fever, diarrhoea and rash and absence of obvious microbial etiology of inflammation, with elevated inflammatory marker, hyponatremia, hypoalbuminemia, and an epidemiologic link to SARS-CoV-2 infection (positive SARS-CoV-2 serology, contact with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case), the diagnosis of MIS-C-Neonate was made. Immunomodulatory therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) 2 g/kg was administered on day 3 of admission along with aspirin in antiplatelet dose. Defervescence occurred within 24 hours of IVIg administration and diarrhoea subsided, and inflammatory markers came down in next 24 hours (Figs. 2&3). Antibiotics were discontinued after 5 days.

Fig. 1

Rash over forehead and cheeks.

Fig. 2

Temperature variation of baby during NICU stay (IVIg- Intravenous immunoglobulin).

Fig. 3

Fall of C-Reactive protein (CRP) in the index case.

Baby remained hemodynamically stable throughout his stay and did not require any respiratory support and was discharged on day 6 of admission on exclusive breast feeds, and anti-platelet therapy with advice of deferment of immunisation with live vaccines due to IVIg administration. Post discharge after 5 weeks, baby remain afebrile, active, 2-D Echo was normal, and neutropenia resolved without any complications (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of the newborn.

3Discussion

MIS-C is diagnosed in children or adolescents with presence of fever > 38.0°C for≥24 hours, elevated marker of inflammation with multisystem (> 2) organ involvement (cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermatologic or neurological), absence of alternative plausible diagnoses; along with evidence of current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection or exposure to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case within the 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms [9]. In our case persistent fever with multisystem involvement (abdominal symptoms, rash) and laboratory evidence of inflammation along with the epidemiologic evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection clinched the diagnosis of MIS-C-Neonate which responded quite well to intravenous immunoglobulin. In this case, it is not clear when did our baby get exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Probably, he was exposed in utero or perinatal period though we do not have evidence of it, considering baby and his father tested negative for COVID-19 and mother tested positive but asymptomatic at the time of testing. Possibly mother’s febrile illness a week before delivery was due to COVID-19 infection and she apparently recovered before delivery without being tested. However, she tested positive probably due to persistence of virus in respiratory secretions [10]. Studies have shown passive transfer of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies through placenta as well as through breast milk [11, 12].

Kappanayil M et al. reported a MIS -C -Neonate in a 24-day old baby girl born at term gestation who presented with severe myocarditis, shock, multiorgan dysfunction, elevated inflammatory markers, and serological evidence of COVID-19 infection (IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2) [7]. However unlike our case, mother had RTPCR positive mild COVID-19 infection at 31 weeks of gestation which resolved with symptomatic and supportive treatment. Khaund Borkotoky R et al. reported a case of a term neonate who developed persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) of newborn without obvious etiology and subsequently had clinical and laboratory evidence of MIS-C between days 12 and 14 of life while being treated for PPHN [8]. Three weeks prior to delivery, mother had a mild febrile illness lasting 3–4 days with history of similar illness in family. She was tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of delivery, however, both mother and baby were positive for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies.

Usually MIS-C is seen in older children with median age at presentation varying between 8 years and 10 years [13, 14]. Precise pathogenesis of MIS-C is unknown, and a post infectious immunologically mediated pathogenesis has been hypothesized which include autoantibodies because of viral mimicry of the host, antibody, or T-cell recognition of viral antigens on virus infected cells, activation of inflammatory cascade by immune complexes and viral superantigen sequences which activate host immune cells [5, 15]. Alice et al showed hyperinflammatory response at the maternal-fetal interface, however, its role in development of MIS-C-Neonate needs further studies [16].

MIS-C is characterized by lymphopenia and up to one third of patients with COVID-19 infection is usually associated with lymphopenia and neutrophilia [17]. In our case, neutropenia developing during course of illness which persisted on follow up. Neutropenia has been reported in a neonate with COVID-19 infection [18]. Bouslama B et al., reported neutropenia in a 5-month-old boy with MIS-C who required filgrastim [19]. Possibly, hematologic-immunologic response to COVID-19 infection is somewhat different in smaller infants and further data needed to elucidate neutropenia in infants with MIS-C.

We need more data to discern the impact of passive transfer of Covid antibodies through placenta & breast milk so that proper guidelines can be laid down for management of Covid exposed pregnant women and their neonates. Neonates with MIS-C should be monitored for persistent neutropenia and associated risk of sepsis. These neonates also require long term cardiac follow up as we still do not have long-term data on impact of MIS-C on coronary arteries.

4Conclusions

In summary, we report a rare case of MIS-C-Neonate with first of its kind with persistent neutropenia. MIS-C in neonates is uncommon and can easily mimic neonatal sepsis leading to delay in diagnosis. Although overlapping clinically with sepsis, fever in neonates is uncommon and fever with elevated inflammatory markers during COVID-19 pandemic should alert the pediatrician to the possibility of MIS-C-Neonate. Also, it is important that mother may test positive concurrently with ongoing MIS-C-Neonate following uneventful undetected COVID-19 infection during last week of pregnancy due to viral persistence in respiratory secretion leading to detection by RT PCR. Neutropenia may be seen in MIS-C-N and warrants prolonged follow up.

Funding source

No external funding for this manuscript.

Financial disclosure

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interest

The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Consent

Consent from parents was obtained.

References

[1] | World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director- General’s opening remarks at the media briefing onCOVID-19:11 March 2020. |

[2] | Gupta A , Madhavan MV , Sehgal K , Nair N , Mahajan S , Sehrawat TS , et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. (2020) ;26: (7):1017–32. |

[3] | Mehta NS , Mytton OT , Mullins EWS , Fowler TA , Falconer CL , Murphy OB , et al. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): What do we know about children? A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) ;71: (9):2469–79. |

[4] | NATIONAL NEONATOLOGY FORUM (NNF) COVID-19 REGISTRY GROUP. Outcomes of neonates born to mothers with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - National Neonatology Forum (NNF) India COVID-19 Registry. Indian Pediatr. (2021) ;20: , S097475591600300. |

[5] | Jiang L , Tang K , Levin M , Irfan O , Morris SK , Wilson K , et al. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) ;20: (11):e276–e288. |

[6] | Radia T , Williams N , Agrawal P , Harman K , Weale J , Cook J , et al. Multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children & adolescents (MIS-C): A systematic review of clinical features and presentation. Paediatr Respir Rev. (2021) ;38: :51–7. |

[7] | Kappanayil M , Balan S , Alawani S , Mohanty S , Leeladharan P S , Gangadharan S , et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a neonate, temporally associated with prenatal exposure to SARS-CoV-2: A case report. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2021) ;5: (4):304–8. |

[8] | Khaund Borkotoky R , Banerjee Barua P , Paul SP , Heaton PA . COVID-19-related potential multisystem inflammatory syndrome in childhood in a neonate presenting as persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2021) ;40: (4):e162–e164. |

[9] | Vogel TP , Top KA , Karatzios C , Hilmers DC , Tapia LI , Moceri P , et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults (MIS-C/A): Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. (2021) ;39: (22):3037–49. |

[10] | Zapor AM . Persistent Detection and Infectious Potential of SARS-CoV-2 Virus in Clinical Specimens from COVID-19 Patients. Viruses. (2020) ;12: (12):1384. |

[11] | Ciobanu AM , Dumitru AE , Gica N , Botezatu R , Peltecu G , Panaitescu AM . Benefits and Risks of IgG Transplacental Transfer. Diagnostics (Basel). (2020) ;10: (8):583. |

[12] | Gao X , Wang S , Zeng W , Chen S , Wu J , Lin X , et al. Clinical and immunologic features among COVID-19-affected mother-infant pairs: antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 detected in breast milk. New Microbes New Infect. (2020) ;37: :100752. |

[13] | Pouletty M , Borocco C , Ouldali N , Caseris M , Basmaci R , Lachaume N , et al. Paediatric multisystem infammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 mimicking Kawasaki disease (Kawa-COVID-19): A multicenter cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. (2020) ;79: (8):999–1006. |

[14] | Feldstein LR , Rose EB , Horwitz SM , Collins JP , Newhams MM , Son MBF , et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in US Children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. (2020) ;383: (4):334–46. |

[15] | Kabeerdoss J , Pilania RK , Karkhele R , Kumar TS , Danda D , Singh S . Severe COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, and Kawasaki disease: Immunological mechanisms, clinical manifestations and management. Rheumatol Int. (2021) ;41: (1):19–32. |

[16] | Lu-Culligan A , Chavan AR , Vijayakumar P , Irshaid L , Courchaine EM , Milano KM , et al. Maternal respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy is associated with a robust inflammatory response at the maternal-fetal interface. Med (N Y). (2021) ;2: (5)::591–610.e10. |

[17] | Kabeerdoss J , Pilania RK , Karkhele R , Kumar TS , Danda D , Singh S . Severe COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, and Kawasaki disease: immunological mechanisms, clinical manifestations and management. Rheumatol Int. (2021) ;41: (1):19–32. |

[18] | Venturini E , Palmas G , Montagnani C , Chiappini E , Citera F , Astorino V , et al. Severe neutropenia in infants with severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by the novel coronavirus infection. J Pediatr. (2020) ;222: :259–61. |

[19] | Bouslama B , Pierret C , Khelfaoui F , Bellanné-Chantelot C , Donadieu J , Héritier S . Post-COVID-19 severe neutropenia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2021) ;68: (5):e28866. |