Factitious Disorder Presenting as the Intentional Swallowing of Foreign Objects

Abstract

Background:

Factitious disorder (FD) imposed on self is a psychiatric disorder characterized by the intentional feigning of symptoms or the self-inflicted production of symptoms in the absence of an obvious external reward.

Case:

This report describes a severe case of FD imposed on self in a 31-year-old male who frequently presented to several regional Emergency Departments with intentional ingestion of foreign objects, ultimately requiring 32 esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and 28 gastroscopy procedures over two years. Significant history of frequent suicide attempts via medication overdose and clinical suspicion of drug-seeking behavior complicated the case. Motivating factors for the patient’s behavior, suicidality in FD, and thepatient’s treatment and outcome to date will be discussed.

Conclusion:

There is no well-established treatment for FD documented in the literature. High-quality studies and additional reports of FD could help clinicians when managing such a challenging diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

The defining feature of Factitious Disorder (FD) imposed on self is the intentional feigning of symptoms or self-injurious behavior in the absence of an obvious external reward [1]. The most severe, chronic, or dramatic cases are termed “Munchausen syndrome” which is the historical name for the disorder. Although most literature suggests that females are more commonly diagnosed with FD, the most severe cases are typically observed in males [2]. Other risk factors include being unmarried, current or past employment in healthcare, previous psychiatric history, and history of family conflict or abuse [3– 7]. One retrospective study of 49 patients with FD found approximately half of subjects self-reported a history of sexual and violent/physical abuse. 43% of subjects also reported history of abuse within the household [7]. Gender differences in the clinical course of FD and correlation with other demographic factors have not been adequately studied, but gender differences in medical specialty treating patients with FD do exist. A systematic review found that the majority (77%) of FD cases involving cardiology were in male patients, while females were more commonly treated by allergy and immunology, infectious disease, and ophthalmology [8].

Current literature disagrees on the prevalence of FD with studies finding rates between 0.1 and 8% in the general population, although most studies have found the incidence to be near 1% [3, 9, 10]. Multiple theories for the pathogenesis of FD have been proposed, but most studies point to the behaviors exhibited as a coping mechanism to address emotional stress and to resolve unmet needs such as attention, care, acceptance, and belonging [3, 11, 12]. The behavior could also be related to the need for the patient to “establish an identity” as one study has suggested [13]. Notably, FD appears to commonly co-occur with additional psychiatric diagnoses. A retrospective review found 32.3% of FD patients to have other DSM diagnoses and between 8.6 to 15.1% of FD patients to have chemical dependency [4]. Depressive disorders appear to be the most common co-occurring psychiatric disorders among patients with FD [3, 8]. Differential diagnosis of FD includes somatic symptom disorder, malingering, conversion disorder, and borderline personality disorder as well as organic causes of symptomatology [13].

CASE

The patient is a 31-year-old male who presented to regional healthcare institutions in an Appalachian area over the past seven years with primary complaints of intentional foreign body ingestion as well as self-reported suicide attempts. His documented past psychiatric history included diagnoses of bipolar disorder with psychotic features, schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. The patient’s past social history was remarkable for homelessness, childhood neglect, and childhood sexual assault. Ingested foreign bodies have included (but are not limited to) batteries, mechanical nuts, bolts, screws, nails, and razor blade cartridges. Over the previous two years, the patient had undergone approximately 85 abdominal x-rays (Fig. 1) to monitor the passage of various foreign bodies throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, the patient had required approximately 32 esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) procedures and 28 gastroscopies in an effort to retrieve foreign bodies over the previous two years. Remarkably, the patient had not experienced bowel perforation from his persistent foreign body ingestion.

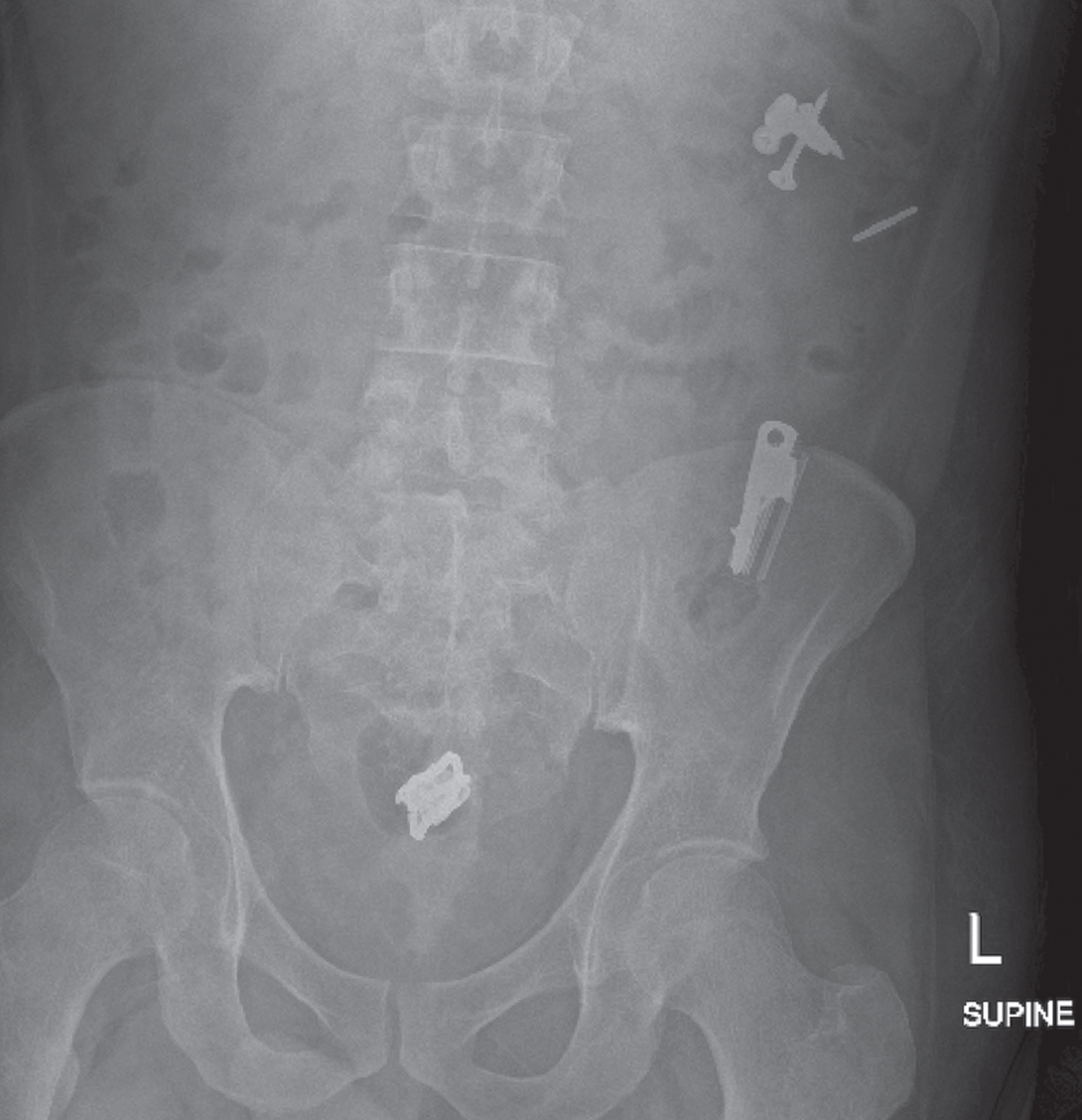

Fig. 1

Abdominal x-ray depicting screws and nails in the left upper quadrant, likely in the distal transverse colon or small bowel. There is a linear radiodense structure over the proximal descending colon as well. Multiple radiodense structures are depicted over the mid-descending colon, which are seemingly a nail, razor blade cartridge, and another irregularly shaped object. Multiple overlapping radiodense structures can also be seen projecting over the rectum.

Due the patient’s history of recurrent foreign body ingestion and suicide attempts, he had further been evaluated voluntarily at several inpatient mental health facilities. He had previously been treated with scheduled psychotherapy sessions and several trials of psychotropic medications, including sodium valproate, quetiapine, aripiprazole, sertraline, ziprasidone, citalopram, escitalopram, and gabapentin for the various aforementioned psychiatric diagnoses. No treatment modality prevented the patient’s continued foreign body ingestion and suicide attempts, although he had shown some improvement with sodium valproate based on chart review. Unfortunately, the suicide attempts by the patient most often involved overdose of prescribed medications such as sodium valproate and citalopram. Upon his most recent admission to an inpatient mental health facility, the patient was evaluated for FD. Although never documented in his medical record prior to this admission, extensive chart review was performed and ultimately revealed persistent features consistent with that of FD. Specifically, it was found that the patient met all key diagnostic criteria in the DSM-V for FD including self-induction of injury or disease, presentation to others as ill, impaired, or injured, evident deceptive behavior in the absence of obvious external rewards, and lack of behavior better explained by another mental disorder [1].

DISCUSSION

Although there are numerous case reports and case series in the literature describing FD, limited case reports of FD specifically involving theintentional swallowing of foreign objects exist. This case adds to the literature as an example of severe FD manifesting as the intentional swallowing of non-nutritional objects and additional reported suicide attempts via medication ingestion. Motivating factors for the patient’s behavior, suicidality in FD, and the patient’s treatment and outcome to date will be discussed.

Perhaps the most important criterion for FD in the DSM-V is the absence of obvious external reward and lack of motivating factor for the patient’s either reported or genuine self-inflicted symptoms. However, drug-seeking was considered as a possible motivating factor for the behavior of the patient presented here. The patient’s frequent ingestion of foreign objects inevitably resulted in multiple EGD’s which always require sedative anesthesia. It is possible that this patient had a physical and chemical dependence on opioids and other sedating medication. Perhaps as a result of his comorbid substance use disorder (SUD), he routinely swallowed objects to obtain the anesthetics required during EGDs.

However, the patient was never clinically evaluated specifically for SUD, and it was not clear from chart review if sufficient criteria were met for the diagnosis. Additionally, most individuals with SUD and/or chemical dependency on analgesia and anesthesia-providing drugs often obtain such substances illegally or by medical prescription. They do not intentionally swallow foreign objects with the goal of requiring a sedative procedure to obtain the sedative or analgesic substance. Although this patient’s presenting signs and symptoms were most consistent with FD, in recent hospitalizations the patient has exhibited more aggressive behavior such as demanding intravenous pain medication, being combative with staff, and requiring restraints during hospital stays. This behavior is a new development for this patient and could lend support to additional psychiatric diagnoses beyond SUD or FD,such as bipolar disorder with psychotic features with which he had been previously diagnosed. Metabolic or toxicologic disturbances could also contribute to this patient’s aggressive behavior, especially with the multiple intentional overdoses reported in the patient’s history.

The issue of co-occurring suicidal ideation with FD is of particular relevance to this case. The patient had endorsed a long history of major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation. He had been seen in the emergency department with multiple intentional ingestions of various substances including salicylates, acetaminophen, and his prescribed medications which the patient claimed were suicide attempts. However, for the majority of these admissions, medical evidence and clinical testing was unable to substantiate these claims. For example, shortly after discharge from an episode of inpatient mental health treatment, the patient re-presented to the ED claiming to have swallowed an entire bottle of aspirin. However, serial salicylate level testing over 48 hours revealed the patient’s blood salicylate level to never rise above 30 mg/dL (normal range: 15-30 mg/dL). At another presentation, the patient claimed to have taken 80 citalopram pills. Poison control was subsequently consulted, and due to the patient’s suspicious history and frequent presentations with similar complaints, the patient was admitted for monitoring. However, 24-hour observation revealed a lack of QTc interval prolongation, lack of serotonergic signs, and complete blood count and serum electrolytes within normal limits. Due to these findings, the patient was then discharged without further treatment.

Although many presentations of this patient with suicidal claims lacked clinical or laboratory evidence of the reported ingestion, the issue of suicidality in this patient was further complicated by the fact that some of his claims were substantial. For example, at one visit to the ED, the patient presented claiming he had swallowed 17 sodium valproate pills, and lab monitoring did reveal a sodium valproate level of > 300 mcg/mL (normal 50-100 mcg/mL) prompting an ICU stay with serial monitoring. Treating this patient at subsequent ED presentations for intentional overdose proved challenging because despite the varied history, every claim of suicidal intent in this patient had to be taken seriously.

Notably, the patient never claimed to swallow objects with the primary motivation of suicide but only attempted suicide via medication ingestion. This could suggest comorbid suicidality in this patient possibly as a manifestation of an additional psychiatric disorder such as major depressive disorder or borderline personality disorder, distinct from and in addition to the FD diagnosis. The primary question for the care provider, then, was whether the self-injurious behavior and reported suicide attempts are symptoms of true suicidal ideation or manifestations of FD. The distinction is important in determining appropriate clinical treatment and care. Unfortunately, adequate literature to aid in the management of patients with FD and suicidality does not exist. One case report with manifestations of FD similar to the one presented here described intentional ingestion of foreign objects with the patient claiming the act to be an effort of suicide [14]. The authors endorse that given the lack of guidance in the literature, careful assessment of suicidality in FD patients is necessary. However, in patients with suicidal ideation existing only as a manifestation of FD, refraining from the overtreatment of the feigned medical condition is also critical as doing so may only serve to reinforce the pathology of FD [14].

Considerations for how to best manage and treat FD is frequently discussed in the literature, but the majority of recommendations are based upon case reports. Long-term, well-designed studies proving the superiority of a specific management approach are lacking. However, some authors have suggested that pharmacologic agents are ineffective [15, 16]. Additionally, FD is clearly a psychiatric problem, and most patients with the diagnosis seem to have had at least one course of inpatient psychiatric treatment for the disorder [17]. However, there are two primary issues with inpatient treatment for FD. First, FD does not normally fulfill requirements for involuntary commitment which is generally limited to patients with risk of imminent harm to self or others or a lack of ability to care for basic needs [13]. Second, further hospitalization and care could serve to further perpetuate the disorder by giving these patients what they desire: attention and medical care. Given that long-term intensive psychotherapy is likely required for successful treatment of FD, outpatient treatment may be pursued and even superior to inpatient management. However, one systematic review found that 60% of patients with FD do not comply with outpatient treatment [18].

Some literature has suggested that early intervention and treatment of FD may lead to improved outcomes [8]. Unfortunately, this was not the case for this patient as he was only admitted to inpatient psychiatric care after the 38th ED presentation for intentionally swallowed foreign objects and/or suicide attempts over two years. Additionally, he was never given a formal diagnosis of factitious disorder, although it is unclear if this diagnosis recorded in the patient’s medical record would have altered management at subsequent ED presentations. However, the patient was made aware their behavior is not normal and that they do need treatment. He always endorsed understanding of his condition and treatment plan and an intention to get better. Specifically, at discharge from the most recent inpatient psychiatric admission, the patient was given a sodium valproate prescription for a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. This had been a prior diagnosis for this patient as well, and he had previously been treated with this medication with questionable improvement. He was also referred for outpatient psychotherapy but did not appear for any subsequent psychiatric or therapy appointments.Perhaps this was due to non-adherence or could be a result of recurrent ED presentations and subsequent hospitalizations that prevented him from appearing for scheduled appointments. To date, the patient has also not improved with the gambit of pharmaceutical agents previously prescribed for other psychiatric diagnoses including SSRIs, atypical antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers. Thus, this case provides additional evidence that pharmaceutical agents have minimal benefit in factitious disorder.

CONCLUSION

The case presented here describes factitious disorder presenting as the intentional swallowing of non-nutritious foreign objects with multiple reported suicide attempts via medication ingestion. The possibility of drug-seeking as the motivation for this patient’s behavior and the suicidal intentions of the patient remain interesting and complicating factors in this case. The unsuccessful psychiatric treatment of this patient is apparent and unfortunately aligns with the frequent treatment failures described in numerous case reports on FD. The lack of adequate research to inform treatment and management of FD remains an issue. Further research on FD would be beneficial in guiding clinicians on how to best manage these patients with a highly complex and difficult-to-treat disorder.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no acknowledgments to report.

FUNDING

The authors have no funding to report.

REFERENCES

[1] | Munro S , Thomas KL , Abu-Shaar M . American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA 2013. Nature. (1993) . |

[2] | McCullumsmith CB , Ford CV . Simulated illness: The factitious disorders and malingering. Vol.34: , Psychiatric Clinics of North America. (2011) . |

[3] | Bass C , Halligan P . Factitious disorders and malingering: Challenges for clinical assessment and management. Vol.383: , The Lancet. (2014) . |

[4] | Krahn LE , Li H , O’Connor MK . Patients who strive to be ill: Factitious disorder with physical symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. (2003) ;160: (6). |

[5] | Catalina ML , Gómez Macias V , de Cos A . Prevalence of factitious disorder with psychological symptoms in hospitalized patients. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria. (2008) ;36: (6). |

[6] | Reich P , Gottfried LA . Factitious disorders in a teaching hospital. Annals of Internal Medicine. (1983) ;99: (2). |

[7] | Jimenez XF , Nkanginieme N , Dhand N , Karafa M , Salerno K . Clinical, demographic, psychological, and behavioral features of factitious disorder: A retrospective analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. (2020) ;62: . |

[8] | Yates GP , Feldman MD . Factitious disorder: A systematic review of 455 cases in the professional literature. Vol.41: , General Hospital Psychiatry. (2016) . |

[9] | Fliege H , Grimm A , Eckhardt-Henn A , Gieler U , Martin K , Klapp BF . Frequency of ICD-10 factitious disorder: Survey of senior hospital consultants and physicians in private practice. Psychosomatics. (2007) ;48: (1). |

[10] | Poole CJM Illness deception and work: Incidence, manifestations and detection. Occupational Medicine. (2009) ;60: (2). |

[11] | Lawlor A , Kirakowski J . When the lie is the truth: Grounded theory analysis of an online support group for factitious disorder. Psychiatry Research. (2014) ;218: (1–2). |

[12] | Kozlowska K Abnormal illness behaviours: A developmental perspective. Vol.383: , The Lancet.(2014) . |

[13] | Sinha A , Smolik T . Striving to Die: Medical, Legal, and Ethical Dilemmas Behind Factitious Disorder. Cureus (2021) ; |

[14] | Blumenfeld EM , Gautam M , Akinyemi E , Mahr G . Suicidality in Factitious Disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. (2020) ;22: (3). |

[15] | Baig MR , Levin TT , Lichtenthal WG , Boland PJ , Breitbart WS . Factitious disorder (Munchausen’s syndrome) in oncology: case report and literature review. Psycho-Oncology. (2016) . |

[16] | Palese C , Al-Kawas FH . Repeat intentional foreign body ingestion: The importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Vol.8: , Gastroenterology and Hepatology. (2012) . |

[17] | Bérar A , Bouzillé G , Jego P , Allain JS . A descriptive, retrospective case series of patients with factitious disorder imposed on self. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) ;21: (1). |

[18] | Eastwood S , Bisson JI . Management of factitious disorders: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. (2008) ;77: (4). |