Prototyping narrative representation system using a Kabuki dance and legendary story for the narration function of robots

Abstract

This study focuses on two stories, Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji, which are deeply related to topics of love and sexuality. Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is a kabuki dance work that is an after-story of the legend of Dōjōji, but the performance comprises mainly dance; thus, the story is expressed only symbolically. Therefore, we attempt to develop a prototype system that associates the story of the legend of Dōjōji with the story of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Specifically, we focus on the positive and negative characteristics observed in the heroine, Shirabyoshi Hanako or Kiyohime and use them to associate the two stories. The proposed system aims to superimpose multiple stories based on a specific aspect of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the heroine’s “mind,” “action,” and “lyrics” sung or narrated on the stage.

1.Introduction

Some thinkers and philosophers state that communal and personal fiction and narratives play important roles in human societies and mentalities. For example, Takaaki Yoshimoto (1968) presented the idea of “communal illusion” to claim that various social institutions are supported by the people’s common illusion or narrative. Additionally, Yuval Noah Harari (2014) discussed the human ability to construct fiction and narratives as the background or basis of their historical progression. We also believe that humans are essentially animals who are capable of imagination and fantasy. Additionally, according to Schank (1986), Minsky (1988), and Mueller (1990), emotions and stories play an important role in human problem-solving activities. In our research framework, “narratives” are the most powerful tools for humans to organize human imagination and fantasy, as well as emotion, to imaginatively simulate diverse aspects of human life. Therefore, robots, including house companion robots (Kheng, Dag, Kerstin & Michael, 2020), which possess artificial intelligence to be able to interact with humans, must maintain a narrative ability-related imagination. In the future, storytelling robots may be required.

Computer-based narrative generation (Ogata, 2019c; 2020a) has been previously researched. Love, sex, and sexuality are often the most important topics in a story. The themes of love and sex appear as representative narratives and literary works in every age. For example, Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji) in ancient Japan and Decameron in medieval Europe treated themes deeply related to love and sex in various hierarchies.11 In the nineteenth century, Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert dealt with immorality, and many novels by Soseki Natsume of Japan frequently describe the love triangles between two men and one woman. In the twentieth century, A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway and Haru no Yuki (Spring Snow) by Yukio Mishima drew a picture of pure love between a woman and a man. Additionally, extraordinary and extreme love and sex have been endorsed, including in the works of Marquis de Sade, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Yukio Mishima, and Georges Bataille. It is necessary to include such subjects in the stories told by robots in the future.

Recognizing the importance of narrative for humans, as mentioned above, the goal of our studies, including this study, is to automate narrative generation. Specifically, we aim to present the concept of “narrative content works,” including an automated narrative generation function that did not previously exist, and develop a system based on this framework. Furthermore, in one of our future studies, we hope to incorporate the developed functions into robots. Wicke and Veale (2018a) and Meza et al. (2016) introduced technologies focused on the relationship between robots and narrative generation or storytelling. In addition to the study of storytelling Veale (2017), research on human–robot interactions Wicke and Veale (2018b), robotic gestures Ham et al. (2011), educational support for children Kory and Breazeal (2014), movie descriptions Rohrbach et al. (2015), and narrative performances Wicke and Veale (2020) has been conducted. As mentioned below, a characteristic of our narrative generation study is the emphasis on the roles of narrative knowledge, such as the cultural and regional values of narratives and human emotions and behaviors regarding love and sex. We aim to connect narrative knowledge to robot technologies in the future. In particular, we plan to combine narrative generation systems using narrative knowledge with narration and actor robots. Cultural elements are also included in this knowledge because the environmental adaptation of robots is closely related to the cultural environment in which they act. Moreover, future robot technologies can accelerate exchange and communication among diverse cultures. In particular, we deal with narrative and literary works in Japanese culture. Another focal point is love and sex. Future robots that enter diverse human life scenes will necessarily be associated to love and sex. We believe that love and sex robots can function as media for considering various topics in gender studies.

In this study, we deal with narrative generation regarding love and sexuality, aiming at the implementation and application of future narration robots based on the aforementioned concepts. In particular, we deal with kabuki work and the related legendary story as materials and a cultural approach to introduce human elements of love and sexuality into narrative generation. We survey and analyze the characteristics of narrative materials from the viewpoint of the relationships between the positive or bright sides and the negative or dark sides of the narratives. This survey and analysis aim at systematization using a computer program, and this study presents a prototyping system based on a narrative survey and analysis. The following part of this introductory section explains kabuki as an important material in this study and describes the approach to the goal of this study.

In the context of the aforementioned cultural approaches, we focused on the narratives of kabuki (Ogata, 2016; 2018; 2019b; 2020a; 2020b; 2020d) in the process of narrative generation. Kabuki is a representative cultural heritage in Japan that incorporates various types of performing arts from dance and classical performance, such as nō and kyōgen. Kabuki is not only a literary or narrative genre that is different from modern genres, such as those found in novels, but also a collection of traditional myths, legends, folktales, and other narratives, as well as a synthesized genre included in drama, narrative, and literature. Furthermore, because kabuki includes human vivid feelings and eroticism, as well as the primitive and symbolic feeling of love and sex, it can provide many hints and inspiration to approaching love and sex through narratives.

Additionally, although kabuki is a traditional cultural heritage, it is not a traditional geinō (the generic name of performing arts and entertainments) that has been preserved through national protection nor a cultural genre that has been continued as a private business. In contrast, the nation has frequently oppressed kabuki. To survive such disadvantageous conditions, kabuki has positively collected old narratives and entertainment and, simultaneously, contains the innovative energy required to introduce new technologies and ideas for reforming itself. For instance, contemporary kabuki uses new narrative genres, including manga and animation, as its materials and applies various video and computer technologies to representation. In particular, the essential feature of kabuki is the creation of new works through the fusion of tradition and modernity. While many studies have been conducted regarding its preservation and heritage, more recent studies have also investigated kabuki from the viewpoint of technology.

For example, many studies of kabuki have examined how video technology has been introduced to performance. Some researchers have analyzed the preservation of “Shosagoto” (the movements of actors) using motion capture. For example, Oda and Genda (2004) studied the characteristic movements of kabuki using a motion capture system. Omoto et al. (2004) created a model of Minamiza, a traditional kabuki theater, in Kyōto. Kobayashi (2018) focused on actors’ movements, comparing Western dance in the ballet La sylphide with the Japanese dance Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji to examine the creation of dances. The stage of ningyō jōruri Hidakagawa Iriaizakura was also reproduced remotely at the Tokyo University of Technology using a commercially available robot (desktop robot “Premade AI”). In contrast to these studies, we approached the narrative of kabuki from multiple viewpoints.

The significance of this study is that it treats kabuki as a research object and focuses on the narrative of kabuki, which has not previously been surveyed and analyzed from the viewpoint of systematization using artificial intelligence and cognitive science with respect to automated narrative generation. This is a challenge in intelligence systems research, including in artificial intelligence. Kabuki is interesting in that it is a narrative collection of many traditional Japanese narratives. Moreover, from the perspective of developing a system, the narrative of kabuki is a complex system that includes complicated diverse narratives that can be expressed in multiple forms. Similarly, the precise analysis of structures is an immensely important theme in research involving computer systems.

Kawai, Ono, and Ogata (2020a) prepared a method for approaching the theme, and the current study uses Japanese classical stories, including an old legend and the related kabuki work, to tackle the problem of story generation related to love and sexuality. We treated Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji (The Maiden at the Dōjōji Temple), which is a famous kabuki dance work created in the eighteenth century. It is one of many works based on the “legend of Dōjōji,” which has also been related to narratives and picture scrolls and is a latter-day description of the legend of Anchin and Kiyohime. Dōjōji is a temple of the Tendai sect in the Kumano area (in current Japan, Hidakachō, Hidaka, Wakayama prefecture). This temple is the subject of the legend of Dōjōji, which has been recorded for over a millennium. Although this legend has undergone many changes over its long history, it is still well known in Japan. Among the versions of this legend, we focus on the kabuki dance Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, which is considered to represent the modern form of the legend of Dōjōji. We also examined the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the storyline of the legend of Dōjōji.

As an approach to kabuki story generation research, we analyzed the stage structure of the kabuki dance work Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji Kawai and Ogata (2019) and developed a system to simulate it using a 2D animation (Kawai and Ogata, 2020; Kawai et al., 2020a). Furthermore, as the first step in generating a love story, we analyzed two tales, the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, and found that there are differences between the two (Kawai et al., 2020b). Moreover, we integrated narrative generation systems, including explanation generation, into the abovementioned simulation system (Kawai et al., 2020c). Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is based on the legend of Dōjōji, but as a symbolic kabuki work, the story of the legend is not concretely expressed. Therefore, in this study, we developed a prototype system to complement the story using the legend of the Dōjōji temple. The purpose is to present a system that supplements Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji using the background of the legend of Dōjōji and to extend the simulation system of the stage performance structure. In this study, we focused on the fact that, although the background of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is the legend of Dōjōji, the rich story of the legend of Dōjōji is not reflected in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, and forms a symbolic dance work. Although Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji was based on the ancient legend of Dōjōji, all elements of the rich storyline of the legend of Dōjōji were excluded.22 As introduced in Section 2.1, the legend of Dōjōji is dark and cruel. In contrast, Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is, if only briefly, colorized by a bright tone. However, the dark aspects from the legend of Dōjōji appear frequently in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Therefore, although the kabuki dance Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is a story of the legend of Dōjōji, it does not directly represent the story of the legend of Dōjōji. However, we found many hidden relationships between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji. From the viewpoint of love and sex that this study focuses on, although the narrative of the legend of Dōjōji directly represents the contrasting sides of a woman’s love and sexual desire toward a man, Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji symbolically abstracts them behind the bright and flowery dance scenes.

Fundamentally, this study treats Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji, which is the background for conducting an analysis combining narratives, from the perspective of the contrast between the positive and negative characteristics of the heroine. A study on kabuki by Tamotsu Watanabe (1986) inspired this study. Watanabe’s analysis method focuses on three elements of kokoro (mind) (representing human nature), furi (action (as small movements)) (meaning the genres of dances), and kashi (lyrics) (meaning the genres of songs) that continue to change through the dance of Shirabyōshi Hanako, the heroine of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. We have inherited and developed this concept from the perspective of the system. We began by considering the relationships between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji to precisely investigate various elements of the story of the legend of Dōjōji, which lurks in the symbolic narrative of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji (Kawai and Ogata, 2021; Kawai, Ono & Ogata, 2021a).

In this study, we assume that the mind and lyrics in the scene of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji are key to superimposing the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Moreover, we aim to develop a system that can express detailed stories based on legends from various parts of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji built on the correspondence of the legend of Dōjōji. For example, a bright scene in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is associated with scenes in the legend of Dōjōjis that represent or symbolize Kiyohime’s extreme love and sexual desire. Based on the analysis of the correspondence relationships between two of the narratives according to the three keys of mind, action, and lyrics, we propose a new system that combines Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji as a framework using an originally developed 2D animation system of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. This is an idea in which the scenes or events in the legend of Dōjōji are associated with Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji based on the dark atmosphere that occasionally appears in mind, lyrics, and action. This study describes the development of two prototyping systems: (1) a 2D animation system that reproduces the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and (2) a 3D animation system that complements the story of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Although the former system uses music, background, people, and dance of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the dance is limited to a simple presentation because the purpose of the system is to represent the entire stage performance structure. These two systems are related to each other. We analyze the scenes of the legend of Dōjōji and associate them with the scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. The system based on the legend of Dōjōji complements the system based on the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji to represent a complementary explanation using visual imagery.

Therefore, this study extends and integrates the previous analysis of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and its systematization and aims to present a novel concept regarding the system according to the storyline of the legend of Dōjōji to complement the former system. Although Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is a narrative work derived from the legend of Dōjōji, it does not directly describe the narrative of the legend of Dōjōji. In the proposed complementary system, the simulation system based on Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the narrative system according to the legend of Dōjōji is ultimately combined to grant users an understanding of the relationships between the two narratives and ultimately enjoy the story of Dōjōji as a Japanese traditional narrative. We stated two types of narrative analyses, namely, research that integrates previous analysis results of the stage structures of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and research that analyzes the storyline of the legend of Dōjōji, which ultimately allows the development of two types of systems. Artificial intelligence, which is pivotal to this study, is an engineering branch that has cognitive science as a basis. Because the motivation of this study is to explore the framework of human intelligence, analyses of research objects using various methods also serve as important steps in the development of artificial intelligence.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces surveys and analyses of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji. We present several tables representing the storyline of the legend of Dōjōji and the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Moreover, we discuss the relationship between the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji considering the duality of Kiyohime’s characteristic in the legend of Dōjōji. Sections 3 and 4 describe a prototype system according to the flow of the system configuration, the algorithm, and the detailed descriptions based on the above analyses and considerations that use a 2D animation system that we have previously sought. Section 3.4 is the central part of this study, which states a system in which the 3D animation system is based on combining the analysis of the storyline of the legend of Dōjōji with the above-mentioned 2D animation system to associate Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji. In Section 5, we present the system implementation, problems with the developed system, and suggestions for future directions. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

2.The legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko musume Dōjōji

Although Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is a narrative work that was derived from the legend of Dōjōji, it does not directly describe the narrative of the legend of Dōjōji. In this study, we focus on the differences between scenes in the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. In this section, we first explain the legend.

2.1.The legend of Dōjōji and its storyline

The legend of Dōjōji has been handed down in different forms through picture scrolls and narratives for over 1,000 years. It is also called the legend of “Anchin and Kiyohime.” The first form includes, for example, the 129th episode of Honchō Hokke Genki Dainihonkoku Hokekyō Genki (1977), “Kii no Kuni Muro-gouri no Akujo” (An Evil Woman in Muro, Kii Province), and “Kii no Kuni Dōjōji no Sō Hōge wo Utsushite Hebi wo Sukuu Hanashi” (A Monk of Dōjōji Temple in Kii Province Brings Salvation to Two Snakes by Copying the Lotus Sutra) in the 3rd Volume 14 of Konjaku Monogatari-shū (Japanese Tales from Times Past) (1999). There is also the Dōjōji Engi Mabuchi (1983), which is a picture scroll of the Muromachi period. A bird’s eye view of the works of the legend of Dōjōji reveals similarities in the lines of those stories. However, there are differences in scenes such as when the heroine turns into a snake and when crying because of sadness. Dōjōji Engi differs from the previous two in that a woman’s perspective is apparent, such as a woman transforming into a snake that chases after the man, the woman narrating her mental state, and the woman being definitively defined as “the wife of the husband, Kiyotsugu no Shōji’ Yasuda (1989).

We provide a rough outline of the legend of Dōjōji. Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk are headed toward the Kumano region of Japan. On the way, the two monks are asked to stay in a private house where a young woman lives (the name of Kiyohime was given in the Edo period), and she falls in love with Anchin. She approaches Anchin that night, but he lies and leaves the next day, betraying her. Feeling bitter and hateful toward Anchin, she transforms into a big snake. Knowing this, Anchin and the old monk seek assistance from Dōjōji temple where Anchin is hidden in a bell. Kiyohime, on the other hand, finds him and kills him with a bell at the stake.

Narratives and music based on the legend of Dōjōji continued to be produced. Specifically, Nō Dōjōji Nishino (1998) according to Nō Kanemaki, which is not played currently, prepared the construction of the stage for performing Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji was played by Nakamura Tomijūrō I as part III of kabuki-drama Otoko-date Hatsugai Soga in March, Hōreki 3 (1753), at Nakamura-za of Edo (current Tokyo).

Honchō Hokke Genki, Konjaku Monogatari-shū, and Dōjōji Engi have similarities and differences. Kiyohime’s love for Anchin was originally based on her pure personality. However, the love of a betrayed woman turns into jealousy, resentment, anger, and other intense emotions. Finally, she kills a monk in the bell of Dōjōji. This story is quite unusual but can be regarded as a sad love story represented by extreme love and actions derived from love.

The legend of Dōjōji has a comparatively clear storyline. In Table 1, we describe the synopsis of the legend, including six scenes and units based on Honchō Hokke Genki, Konjaku Monogatari-shū, and Dōjōji Engi. In Table 1, “events” temporarily list the main episodes in each scene, and “components” show characters, places, times, and objects in each event. The third scene has a junction structure. The left junction shows the storyline of Honchō Hokke Genki, Konjaku Monogatari-shū, and the right junction describes the storyline of the Dōjōji Engi. Additionally, with regard to symbols P+, P, N, and N+ in the last part of each event, P and N, respectively, mean “positive” and “negative,” and + is the emphasis mark. These symbols will be used to denote the correspondence between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji, as explained in the next section.

2.2.Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji

Although Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji inherits the structure of Nō Dōjōji, the story of the legend of Dōjōji is not represented, except for the scene of the “Kaneiri.” The objective of the lyrics written by Fujimoto Tobun Kineie (2018) is not to describe the story of the legend of Dōjōji, draw various images inspired by the legend, nor change the flow of the dance. In Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the legend of Dōjōji itself is not described but retains the information that forms the background of the work.

The synopsis of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is as follows: Shirabyōshi Hanako visits Dōjōji for a memorial service for the bell. Then, she performs a dance, but, in the end, reveals her true nature, climbs the bell, and glares at the monks of Dōjōji, and the performance ends. In the stage of this kabuki dance, the heroine Shirabyōshi Hanako displays a gorgeous and elegant dance, hoping for the memorial service of the bell of Dōjōji. The legend of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is the after-story of Dōjōji. Hanako has already died; therefore, she is a ghost. In the final scene of the stage, Hanako transforms into a different figure from that of the previous scene, namely an evil and frightful large snake on top of the large bell placed on the right side of the stage. The monks of Dōjōji on the left side of the stage pray for the snake, that is, Shirabyōshi Hanako, and the curtain falls. Therefore, in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the heroine Shirabyōshi Hanako shows different appearances on stage. For example, while dancing, she shows herself as a beautiful daughter and a maiden in love. However, in the final scene, Hanako transforms into a big snake and glares at the surroundings from the top of the big bell installed on the stage. Thus, her appearance differs in each scene. Next, we explain the stage composition.

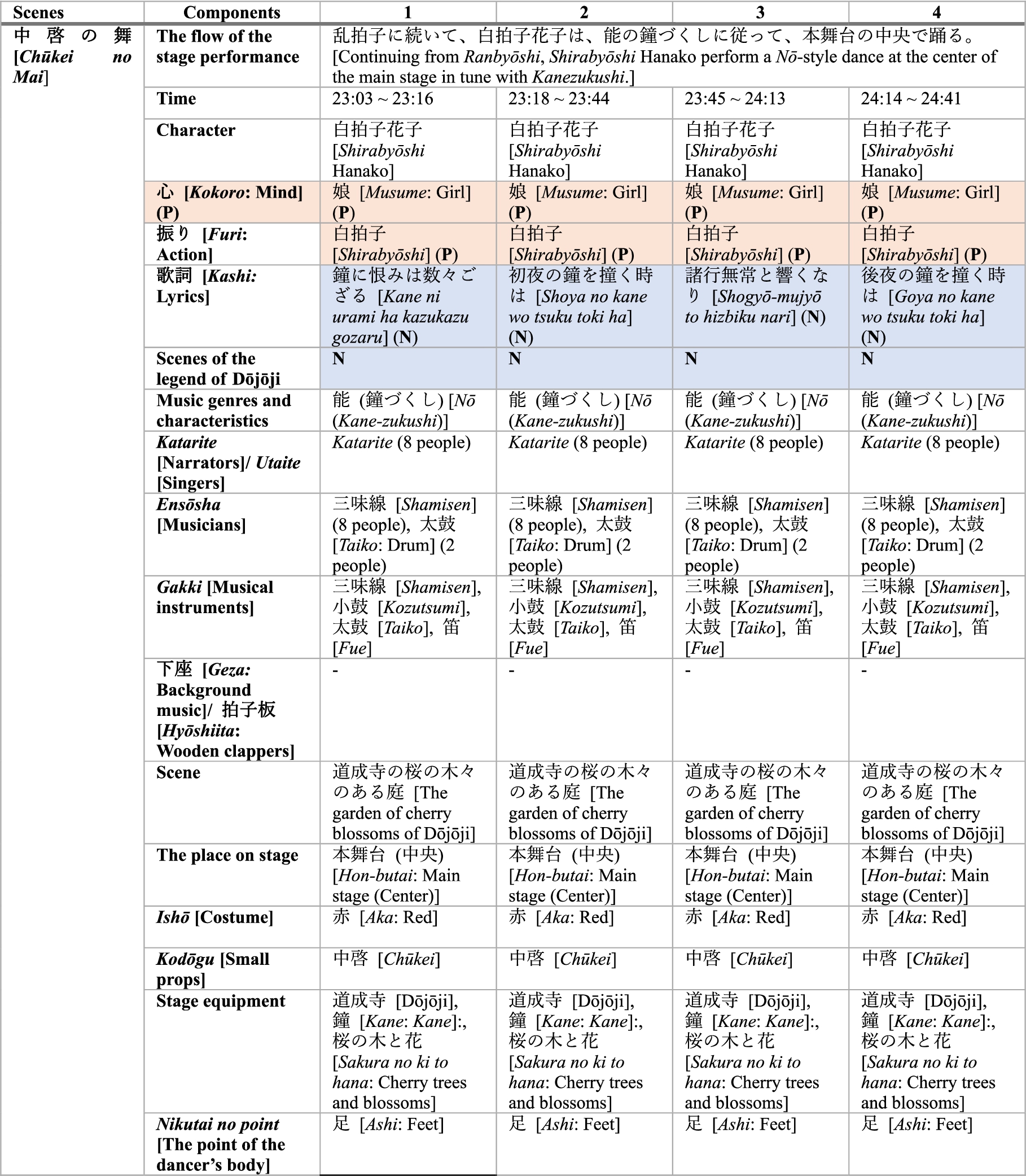

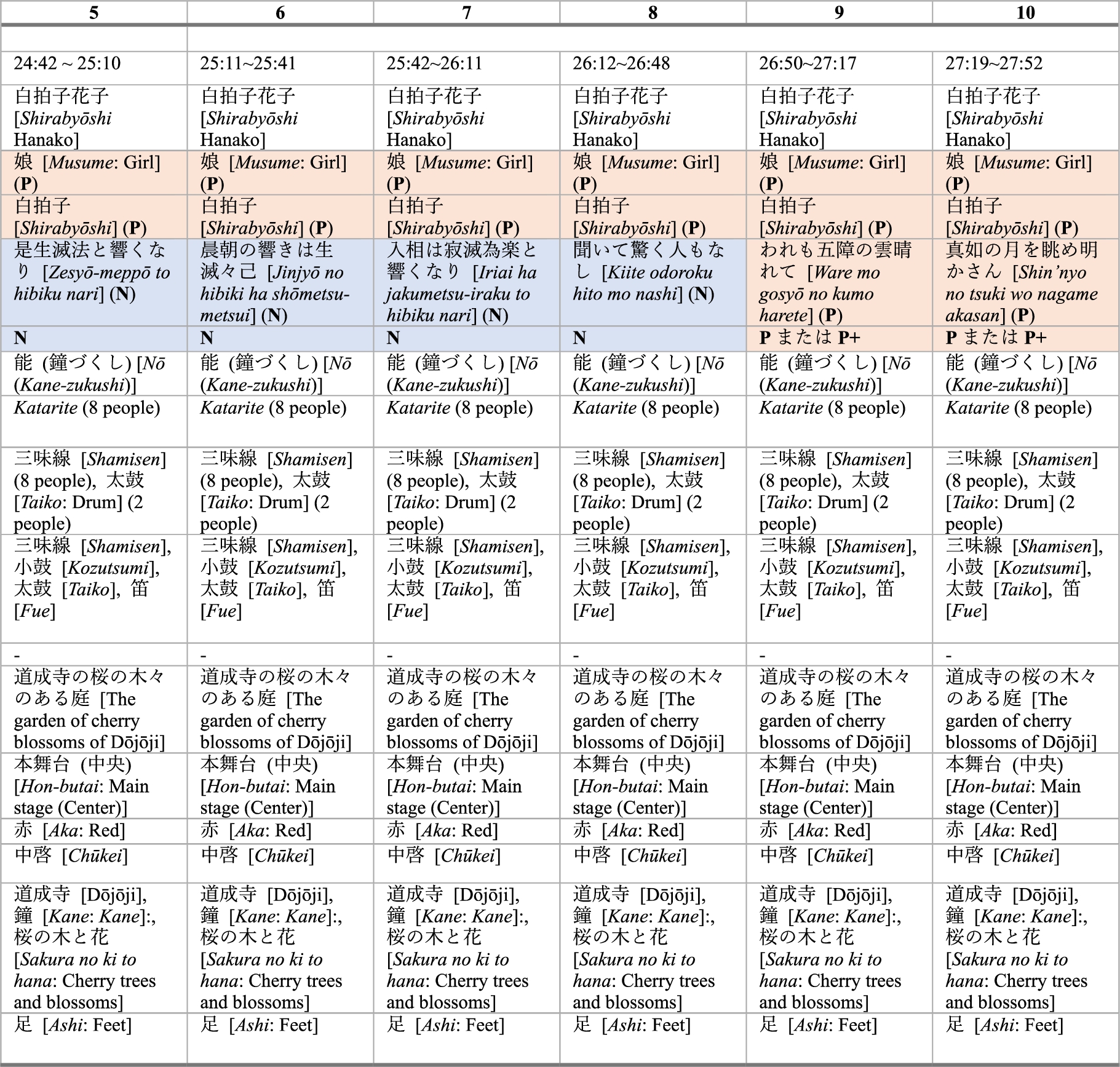

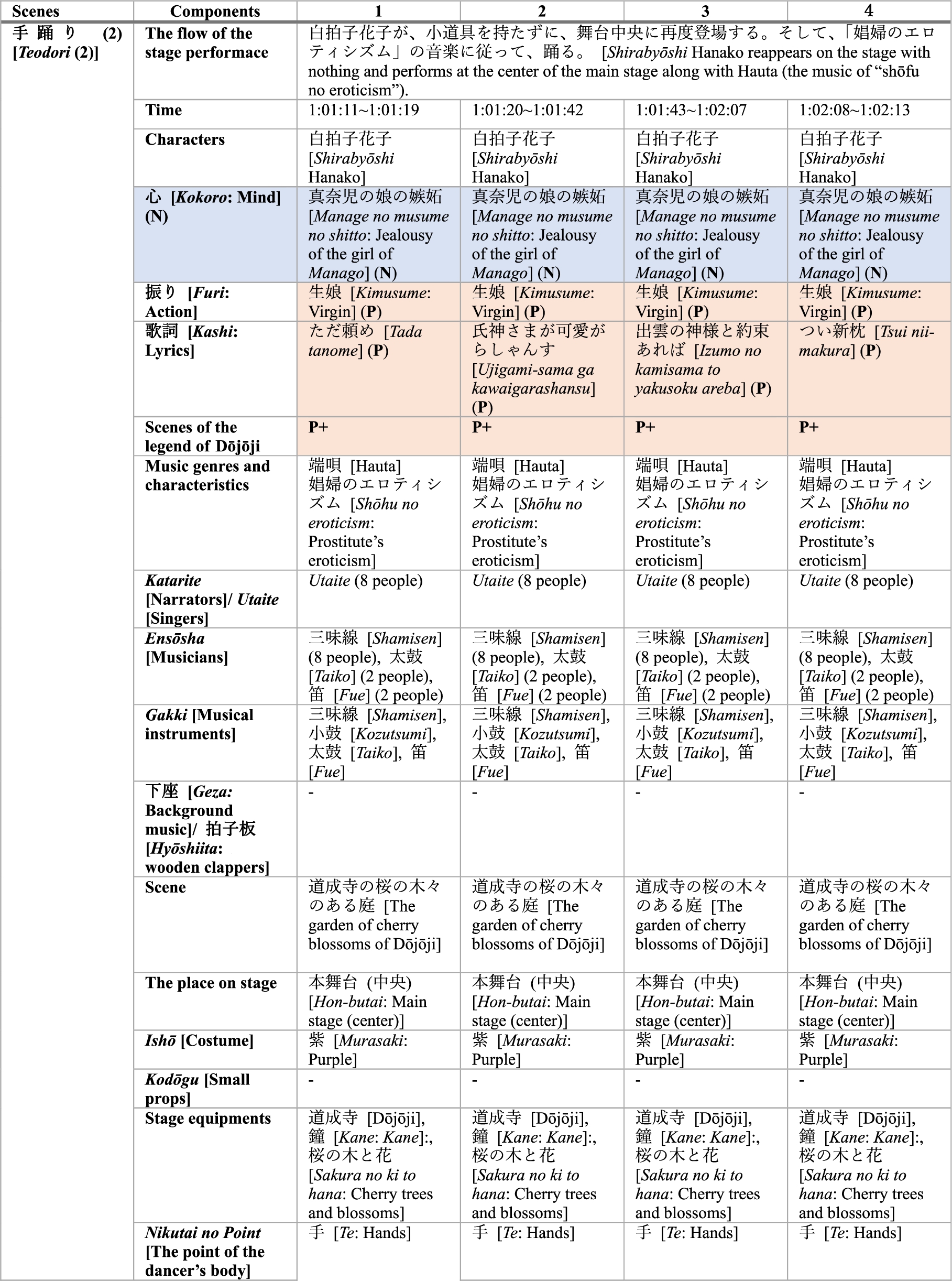

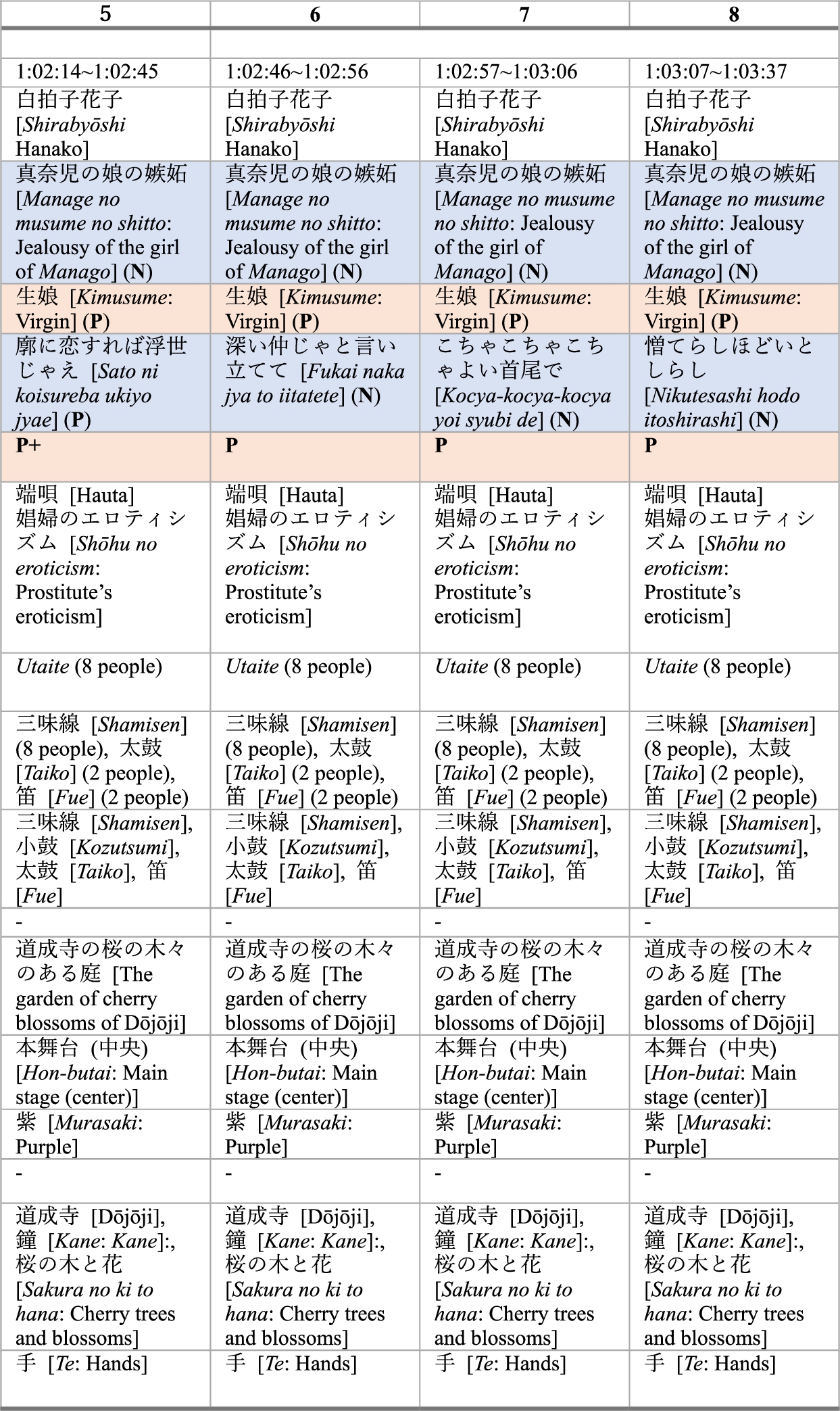

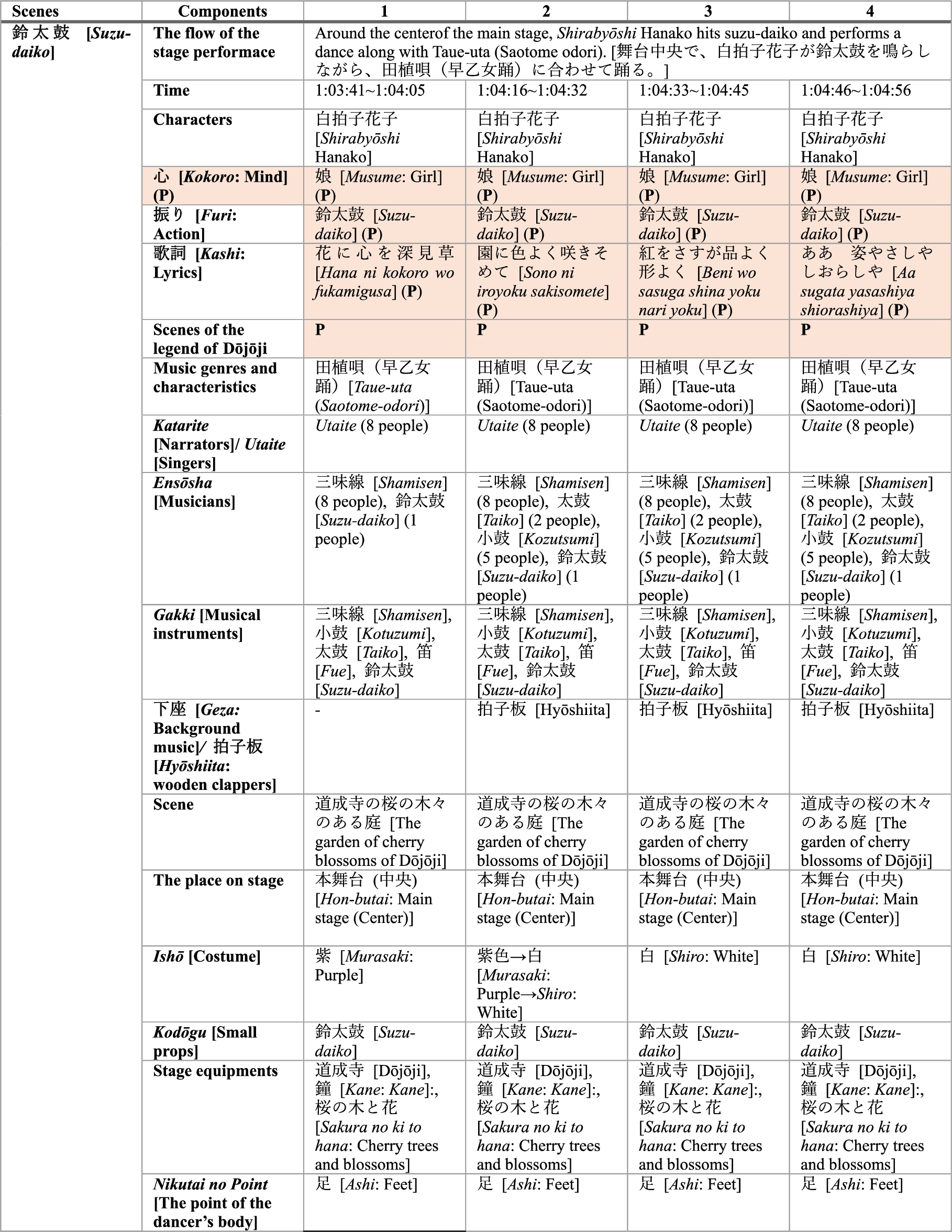

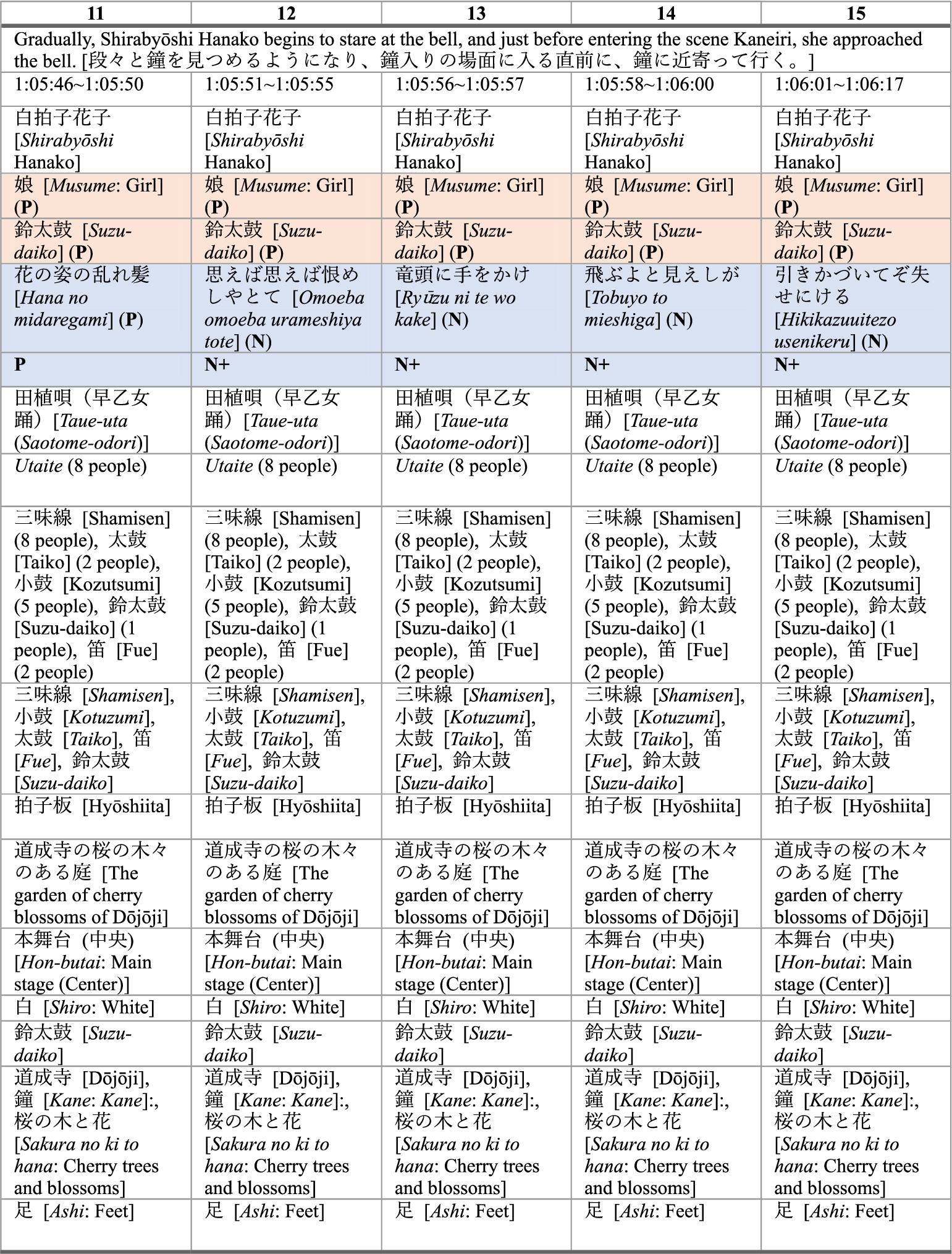

Kawai and Ogata (2019) referred to the analysis table regarding the narrative structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji presented by Watanabe (1986). Although this is a simple analysis table that describes Hanako’s mind, action, the point of her body, lyrics, etc., to show her characteristics of the dance, we added many elements to it to interpret it as the main description of the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Moreover, we created a detailed table representing the stage performance structure based on an analysis of the actual stage record (Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, 2003). Furthermore, Kawai, Ono, and Ogata (in press) created a table that included the flow, appearance image, and lyrics in each scene from the viewpoint of the simulation system of the Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji performance structure. In this study, we created a new integrated table by synthesizing and adjusting these tables. Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the stage performance structures of three scenes: “Chūkei no Mai,” “Teodori (2),” and “Suzu-daiko.” The description unit in each table is based on a unit of Japanese lyrics.

Table 1

Details of scenes in the legend of Dōjōji

| Scene | Components | Events in Each Scene | |

| [1] Kiyohime falls in love with Anchin at first sight. | Characters: Anchin, Old monk, Kiyohime Locations: Kumano, Private house (Kiyohime’s house), Road to temple visit (Kumano) Time: – Objects: – | Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk head to Kumano on a pilgrimage. [P] | |

| Anchin and the old monk stay in a private house. [P] | |||

| Kiyohime, who lives in the private house, falls in love with Anchin at first sight. [P+] | |||

| Anchin lies to Kiyohime about visiting Kiyohime’s house. [N] | |||

| [2] Anchin betrays Kiyohime. | Characters: Anchin, Old monk, Kiyohime Locations: Kumano, Monks’ temple Time: – Objects: – | Anchin and the old monk leave Kumano. [P] | |

| Anchin and the old monk make a detour and return to their temple. [N] | |||

| Kiyohime notices that Anchin lied. [N] | |||

| [3] Kiyohime’s body turns into a snake. | [3-1] Metamorphosis by grief | [3-1] | [3-2] |

| Characters: Kiyohime, Snake (Kiyohime) Locations: Kiyohime’s room Time: – Objects: – [3-2] Metamorphosis by fury Characters: Kiyohime, Snake (Kiyohime), Anchin Locations: Kirime River, On the rocks of Ueno Time: – Objects: Fire | Kiyohime is confined to her room. [N] | Kiyohime crosses the Kirime River. [N] | |

| Kiyohime cries. [N] | Kiyohime chases Anchin. [N] | ||

| Kiyohime’s body turns into a snake. [N+] | Kiyohime sits on a rock in Ueno. [N] | ||

| Kiyohime spits fire. [N+] | |||

| Kiyohime’s body turns into a snake. [N+] | |||

| [4] Anchin and the old monk run away in a hurry. | Characters: Anchin, Old monk, Passers-by, Snake (Kiyohime) Locations: Road (Kumano) Time: – Objects: – | Anchin and the old monk hear from a passers-by that a snake is chasing them. [N] | |

| Anchin and the old monk run away in a hurry. [N] | |||

| [5] Kiyohime burns Anchin to death in Dōjōji Temple. | Characters: Anchin, Old monk, Kiyohime (Snake), Monks of Dōjōji Temple Locations: Dōjōji Temple Time: – Objects: Bell of Dōjōji, Charred corpse | Anchin and the old monk flee to Dōjōji Temple. [N] | |

| The monks of Dōjōji Temple hide Anchin in the bell of Dōjōji. [N] | |||

| The snake arrives at Dōjōji Temple. [N] | |||

| The snake wraps around the bell where Anchin is hiding. [N+] | |||

| The snake spits fire on the bell. [N+] | |||

| The snake leaves. [N] | |||

| The monks of Dōjōji Temple look inside the bell. [N] | |||

| The monks of Dōjōji Temple find Anchin’s charred corpse. [N] | |||

| [6] Anchin and Kiyohime are reincarnated through the Lotus Sutra. | Characters: High-ranking old monk, Monks of Dōjōji Temple, Anchin, Kiyohime, Locations: Dōjōji Temple, In the dream of an old monk Time: Night Objects: | That night, a high-ranking old monk has a dream. [N] | |

| In that dream, Anchin and Kiyohime appear as snakes. [N] | |||

| Anchin and Kiyohime ask the old monk for salvation. [P] | |||

| The old monk and the monks of Dōjōji Temple continue to chant the Lotus Sutra at Dōjōji Temple. [P] | |||

| That night, a reincarnated Anchin and Kiyohime appear in the old monk’s dreams. [P+] | |||

| Anchin and Kiyohime thank the old monk. [P] | |||

| Anchin and Kiyohime disappear from the dream. [P] | |||

Additionally, although Watanabe (1986) deals with 14 scenes, this study considers only 12 scenes until “Kaneiri” according to the above actual performance record. In these 12 scenes, one is a conversation between a shoke (a monk at Dōjōji Temple.) In addition, it was a dance scene. This study focuses on the analysis of dance scenes.33

Notably, Hanako’s mind changes quickly—from a ghost to an innocent girl in love. Among the dance scenes, there are more than five where the mind changes. For example, there is one called Chūkei no Mai. It is a scene where a fan called a Chūkei is incorporated in the dance. Here, Hanako has the mind of a daughter. Next, there is a scene called “Kudoki,” where she is singing a poem about sadness and love. Here, the mind has changed to a daughter in love. In the final scene, with a bell, Hanako reveals her true nature and turns into a snake. She then climbs onto the bell and glares around the stage, and the performance ends. In this way, Hanako’s mind changes multiple times.

The meanings of the “components” in Tables 2, 3, and 4 are shown in Table 5.

2.3.Associating the legend of Dōjōji with Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji based on Kiyohime’s duality

In the legend of Dōjōji, the snake is sometimes treated as a negative symbol because Kiyohime is transformed into one by negative emotions (anger and jealousy).44 Kiyohime has two aspects or characteristics, and we can interpret that the legend of Dōjōji is a narrative in which the positive aspect of Kiyohime changes to a negative aspect. Kiyohime’s mind is currently polarized, but there is also a method of classifying the mind and observing changes in them. We believe that a method for expressing the gradation of the mind, which gradually changes from positive to negative, can be generated as a love story. Although Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is a kabuki dance work drawn in bright color in general, as shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4, it contains Kiyohime’s negative side. We consider this duality of this work based on mind, action, and lyrics to represent the association between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji.

Kawai, Ono, and Ogata (in press) focused on Kiyohime’s two-sided features in the story of the legend of Dōjōji, namely, the aspect of a pure girl who loves a young monk and a girl who goes berserk and betrays him. They divided the scenes of the legend of Dōjōji into P scenes corresponding to the former and the N scenes corresponding to the latter. We divided Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji into P and N scenes, as shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Additionally, Watanabe (1986) mentioned that the mind, action, and lyrics in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji individually have complex structures. Even if the “mind” of a scene is “a pure girl,” her action and lyrics are not necessarily consistent with the mind. For instance, the dance showing the “mind” of “a pure girl” can include contrasting “action” and “lyrics.” According to Watanabe (1986), such complexity is an essential characteristic of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Ogata (2019d) expounded such a narrative feature as a rich form of narrative that is different from the hierarchically organized narrative form claimed by Aristotle (1997). Such a narrative principle indicates that narrative work does not necessarily need to be constructed based on psychological reality. In Japanese literary tradition, for example, the mentalities of many characters of Genji Monogatari have the psychological traits that modern people can sympathize with. Simultaneously, the narrative works of kabuki contain many scenes, episodes, and characters’ mentalities and actions that modern people cannot sympathize with. However, when we view them from the perspective of the representation effects of narrative, kabuki, irrational, at a glance, frequently have impressive dramatic and narrative effects on the audience. Japanese narratives have many elements familiar with “realistic” norms. Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is a typical work.

Table 2

Detailed structure of the scene of “Chūkei no Mai”

Table 2

(Continued)

In this study, we consider that the mind, action, and lyrics individually represent the emotions and characteristics of Hanako to analyze them more precisely. According to Tables 2, 3, and 4, regarding the actions and lyrics in 11 scenes, we focused on the parts that have characteristics different from the mind of each scene.

Table 3

Detailed structure of the scene of “Teodori (2)”

Table 3

(Continued)

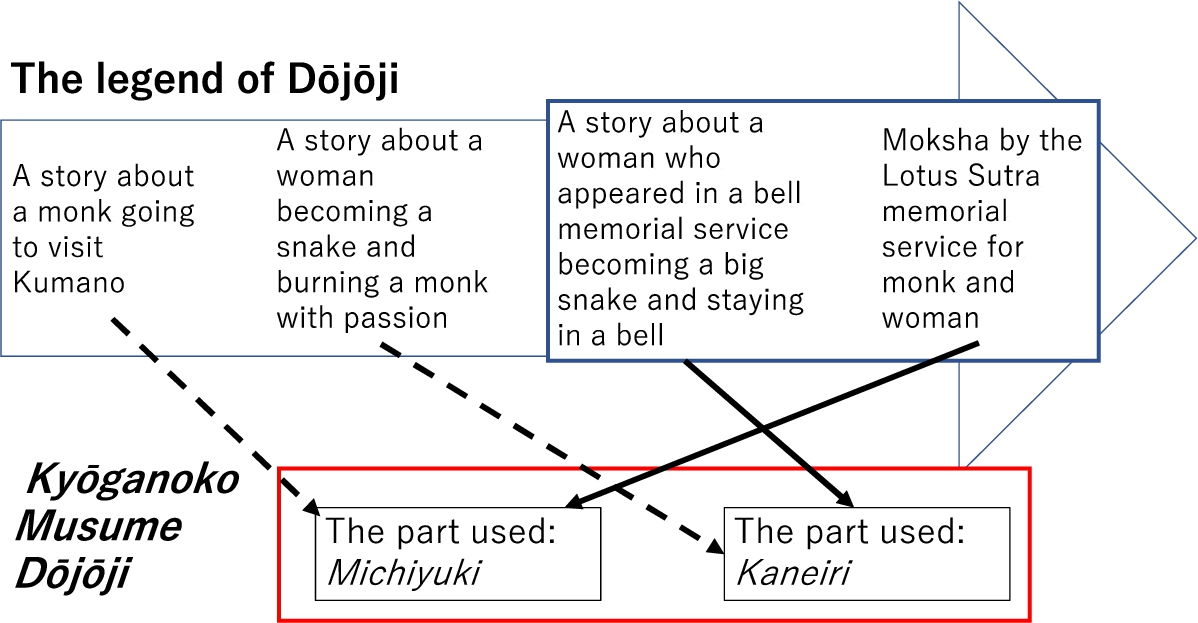

Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji has fewer scenes in common with the legend of Dōjōji than Dōjōji Engi, Hokke Genki, and Konjaku Monogatari shū. It has a thin narrative, is abstract, and does not specifically express the story of the legend of Dōjōji. However, some scenes of Shirabyōshi Hanako correspond to those in the legend of Dōjōji. Figure 1 shows the correspondence between the story of the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. As shown in the figure, the latter uses only two scenes related to the legend of Dōjōji: “Michiyuki” and “Kaneiri.” Both show the true nature of Shirabyōshi Hanako.

Table 4

Detailed structure of the scene of “Suzu-daiko”

Table 4

(Continued)

Figure 1 shows the correspondence between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji at the macrolevel. Although this figure indicates that many of the parts of the story of the legend of Dōjōji are not included in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji several scenes or images in the legend of Dōjōji are reflected in the stage of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. This study focuses on the legend of Dōjōji, which is an essentially dark narrative, being incorporated into Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, which is a bright story.

Table 5

Meaning of the components in tables of the stage performance structure of the kabuki dance

| Component | Meaning |

| The flow of the stage performance | The flow of events played on the actual stage. |

| Time | The time in which the showing of a part of the lyrics is changed to the next. |

| Characters | People appearing on the stage. Although the central character of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is Shirabyōshi Hanako, many shokes also appear in this stage. |

| 心 [Kokoro: Mind] | The word represents the most essential or symbolic mental state of Shirabyōshi Hanako who is a central character in each dramatic scene. |

| 振り [Furi: Action] | The genres of dances played by Hanako. |

| 歌詞 [Kashi: Lyrics] | The lyrics sung or narrated, written by Fujimoto Tobun. |

| The scene of the legend of Dōjōji | It indicates whether the associated scene of the legend of Dōjōji is a negative scene or positive scene. |

| Music genres and characteristics | The genre or features of the music played in each scene. |

| Katarite [Narrators]/Utaite [Singers] | Narrators or singers of the lyrics and their numbers. |

| Ensōsha [Musicians] | The musical players on the stage according to the types of instruments and their numbers. |

| Gakki [Musical instruments] | The types of instruments played on the stage. |

| 下座 [Geza: Background music]/拍子板 [Hyōshiita: Wooden clappers] | Geza is a room that is hidden from the audiences on the left side (as observed from the audience seats) of the stage and the players in the geza mainly play sound effects. On the other hand, Hyōshiita is instruction for a player on the right side of the stage, accompanied by dramatic development. |

| Scene | The background of the stage. |

| Place on stage | Each narrative place where one or more dramatic characters exist. |

| Ishō [Costume] | The costume that Shirabyōshi Hanako wears. |

| Kodōgu [Small props] | Small props that Shirabyōshi Hanako has. |

| Stage equipment | Backgrounds and objects on the stage. |

| Nikutai no point [The point of the dancer’s body] | In each scene, the part of Hanako’s body that is mostly focused on. |

For example, the scene of “Chūkei no Mai” shown in Table 2 is a P scene base on “Mind: Girl” (P). This “girl” means a loving pure girl who has a bright nuance. However, the lyrics from one to eight in this scene represent her N emotion to the bell, and we defined these scenes as N. Here, these scenes are associated with N events (scenes) of the legend of Dōjōji, as shown in Table 1. The parts of the mind, lyrics, and actions in Tables 2, 3, and 4 are described.

Next, because the “mind” which is consistently in the scene of “Teodori (2)” in Table 3, is “Manago no musume no shitto” (Jealousy of the girl of Manago), we defined this entire scene as N. However, her action is continuously colored by the bright and P atmosphere of a virgin girl, and the lyrics are hopeful in the middle of the scene (these are continuously P). In contrast, as the lyrics of the last parts (Sections 5 and 6) show her jealousy, these parts are defined as N. Hence, “Taodori (2),” which is bright, is associated with N episodes of the legend of Dōjōji in the final part.

Finally, “Suzu-daiko” of Table 4, in which the “mind” is “girl,” is entirely positioned as a P scene and the action and lyrics also have a P atmosphere in the middle of the scene. However, the lyrics from scenes 12 to 15 changed to an N atmosphere. This last part is associated with the N scene in the legend of Dōjōji.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji.

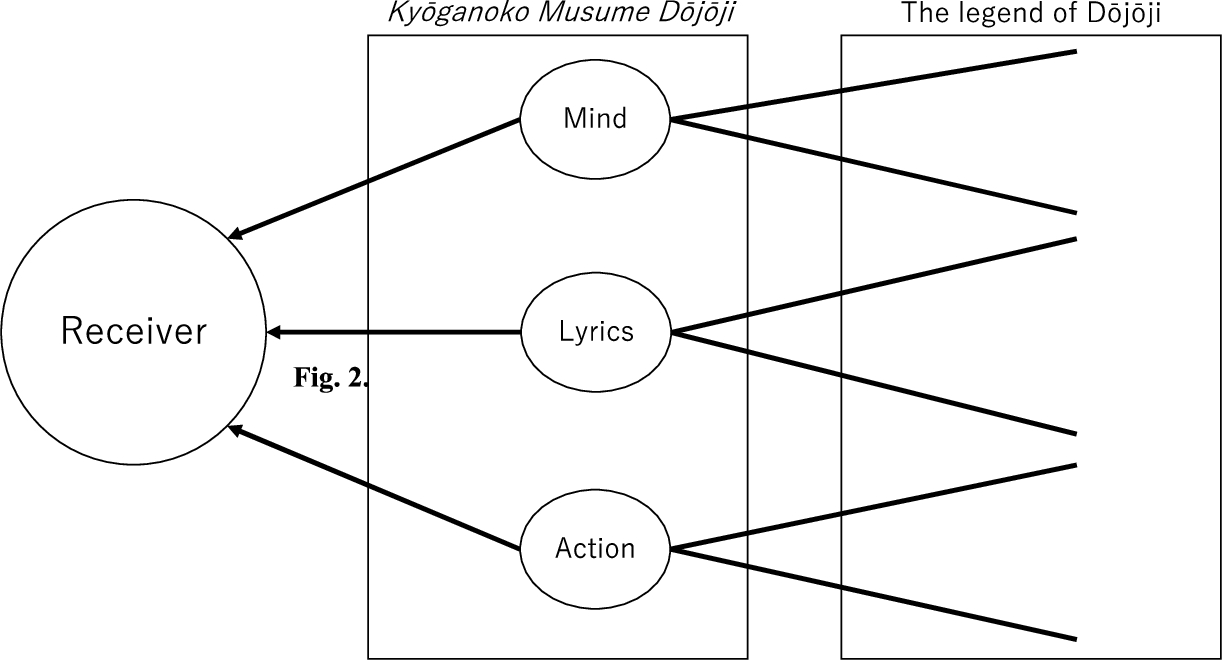

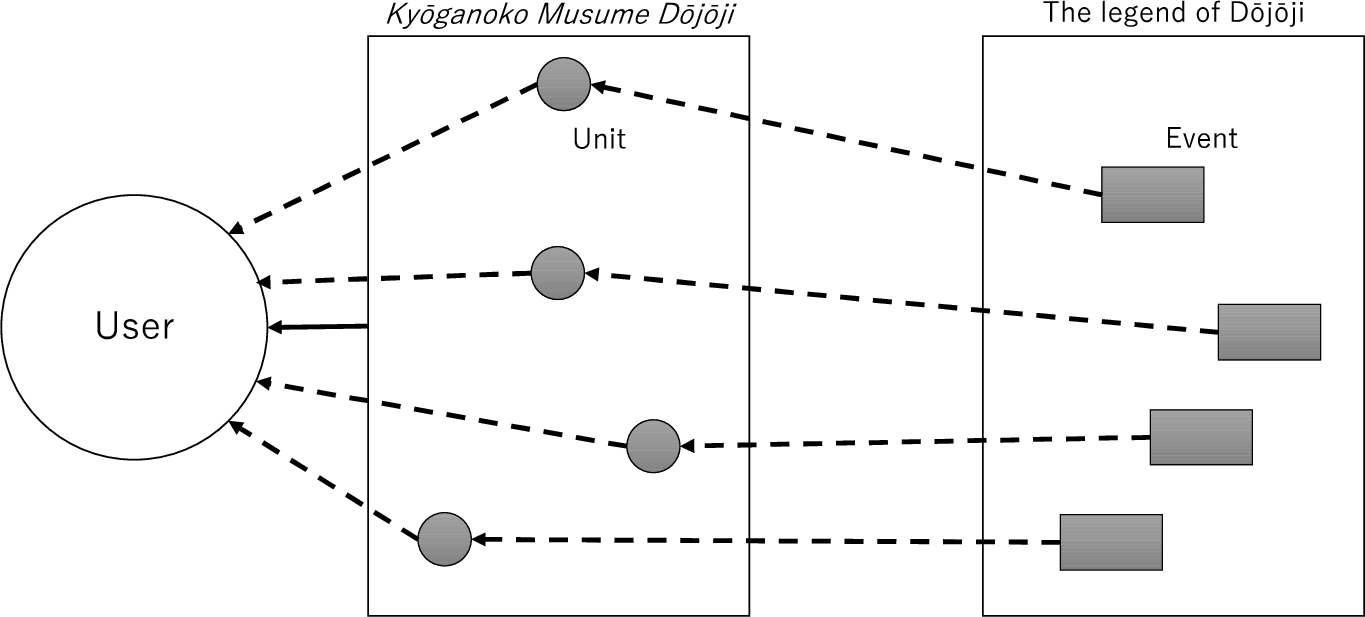

The above description shows that the episodes of the legend of Dōjōji are fragmentally reflected in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Figure 2 shows a conceptual image of the relationship between the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji.

Fig. 2.

Image of the legend of Dōjōji that is fragmentally reflected in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji.

3.Prototyping system

In this section, we propose a prototype system based on the survey and analysis of both the legend of Dōjōji and Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the analysis of their mutual relationships. It associates our simple 2D representation system for the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji with the same simple 3D representation system based on the legend of Dōjōji. In the proposed association system, the simulation system based on Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the narrative system according to the legend of Dōjōji are combined to elucidate the relationships between the two narratives and grant users the enjoyment of the story of Dōjōji as a Japanese traditional narrative. In the following subsections, we show the system configuration, macroalgorithm including two processes, and the 2D representation system.

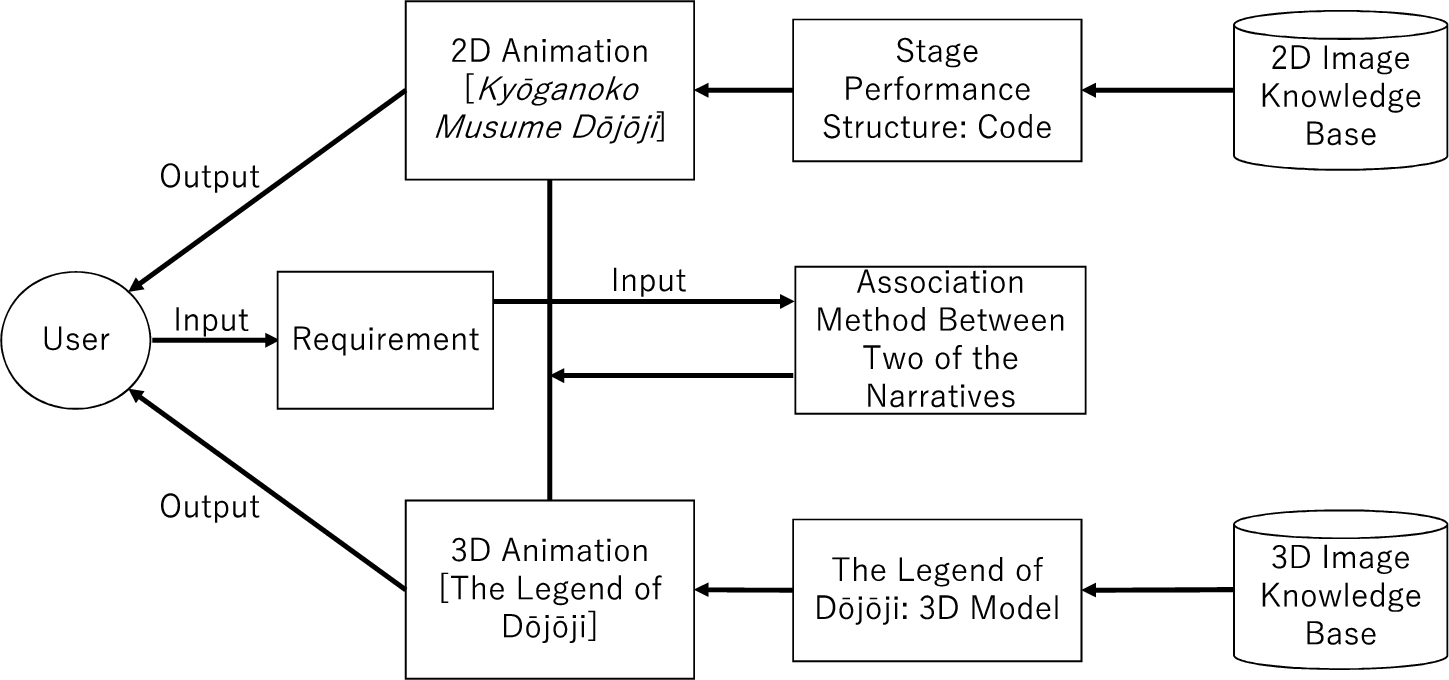

3.1.System configuration

The internal structure of the system is illustrated in Fig. 3. As the flow of the system, based on the stage structure code given to Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji by the user, the stage is reproduced by referring to the image knowledge base for 2D animation. As stated in Section 3.3, the code is a list of commands, such as moving the character and changing the background inside the system. During the 2D animation system performs, different types of systems select a 3D model from the knowledge base according to the corresponding relationship between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji analyzed in the previous sections, generate a scene of the legend of Dōjōji, and insert it into the stage reproduction of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Each scene of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is associated with a scene in the legend of Dōjōji using the correspondence method of both narratives based on the method described in the following section. As we can observe from this description, in the system, the output video is divided into two types: one frame represents the scene of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji using 2D animation and the other of the legend of Dōjōji using 3D animation. When representing, the system uses the knowledge associated with the specific scenes of the legend of Dōjōji with the “lyrics (kashi)” of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the “mind (kokoro)” and “action or movement (furi)” expressed in each scene, as mentioned in the previous sections.

From the users’ perspective, this system is used by, for instance, people who are interested in kabuki but do not know the stories of kabuki in detail. Users can see the computer simulation of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, which is bright in general and appreciates the story’s development. Simultaneously, users can also see that the original episodes of the legend of Dōjōji fragmentally appear similar to in a flashback and get explanations according to “mind,” “lyrics,” and “action” of the heroine as keys. In particular, the role of this proposed system is to change the user’s narrative experience to a more complex one and allow multiple experiences through the story of the legend of Dōjōji, which is hidden in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

System architecture.

Fig. 4.

System image from a user’s perspective.

3.2.Macro algorithm: Two processes

This system comprises two main processes. This processes terminates when all 11 scenes included in the input are processed.

(1) 2D representation system: The system receives a code showing the stage structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji from the user and generates a 2D image of the stage reproduction of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji based on the input code. In particular, the system separates the code based on each scene of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji written in the code and executes the following processing for each scene. When the reproduction of the scenes included in the input is generated, reproduction is stopped, and the result and input code are given to the next mechanism. The 3D representation system is based on the 2D representation system and the legend of Dōjōji. The 2D representation system has already been developed, and an overall explanation is provided in Section 3.3.

(2) 3D representation system and the mechanism associated with the 2D representation: The system receives the input code and the video generated in 2D and inserts the scene of the legend of Dōjōji into the stage reproduced video of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji based on the corresponding knowledge base, the legend of Dōjōji. After processing, the stage reproduction of Musume Dōjōji, whose story is complemented, is returned to the user. Section 3.4 provides a detailed description.

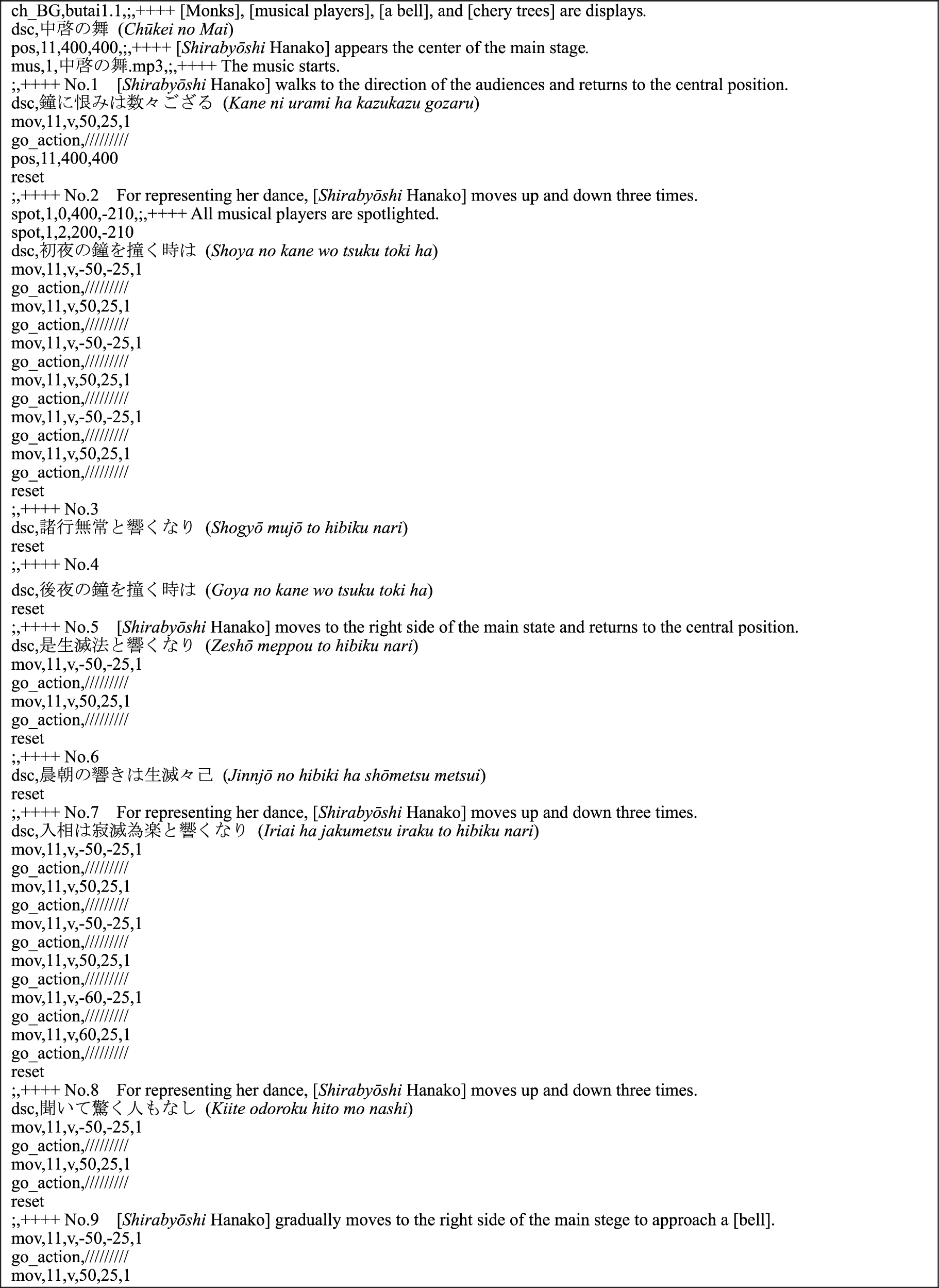

3.3.2D representation system of the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji using KOSERUBE

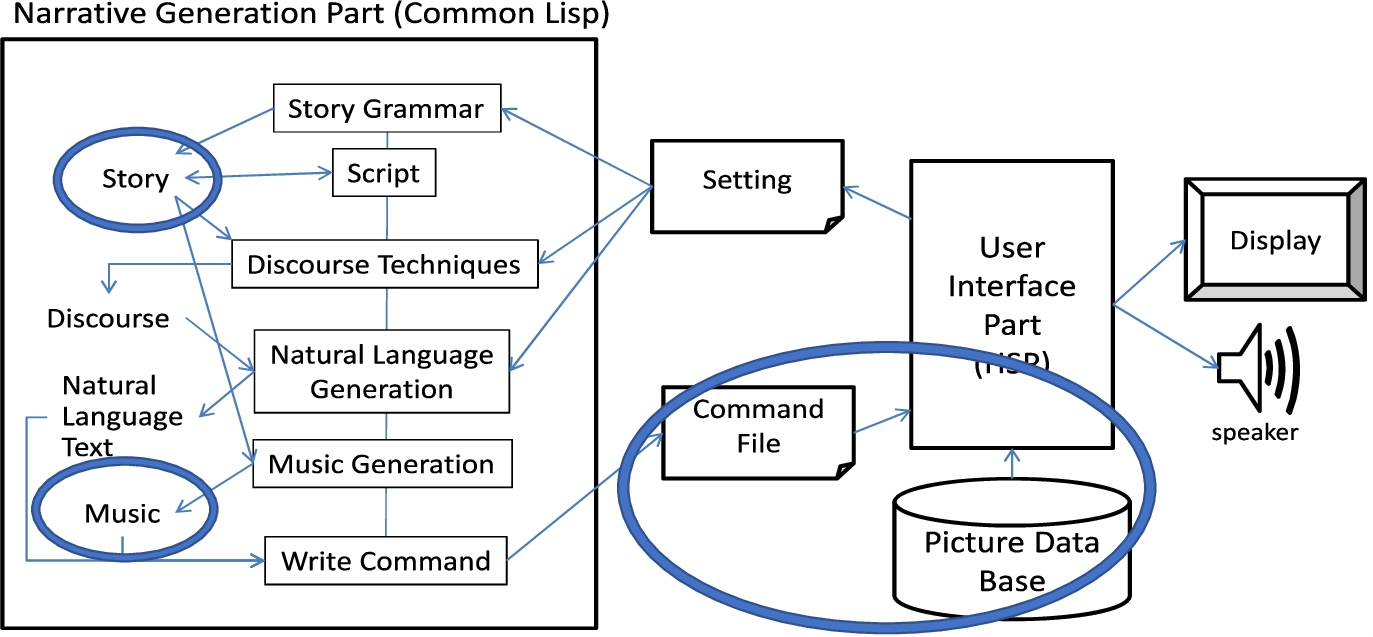

The 2D representation system uses part of the functions of the system called KOSERUBE. Figure 5 presents an overview of the KOSERUBE architecture. KOSERUBE comprises two parts: a narrative generation module and a user interface. Each part is implemented using Common Lisp and HSP and connected via input and output files.

KOSERUBE uses the narrative generation mechanism developed in this study. Narrative generation in our system architecture of narrative generation is executed as a structural operation in the story, discourse, and expression. Each process is performed by four main functional components: conceptual dictionaries, story techniques, discourse techniques, and control modules. Conceptual dictionaries provide semantic definitions of the components of an event, which is a fundamental element of the narrative. Story techniques are used to build a story structure. Discourse techniques are generative rules that transform parts of a story structure. The control modules manage the entire generation process. The conceptual dictionaries and mechanisms above comprise integrated narrative generation. A detailed description was provided by Ogata (2018; 2019a; 2020c). Additionally, KOSERUBE mainly uses the above dictionaries and mechanisms. The difference is the story technique and music mechanism. The central technique for the story-generation phase is Propp-based story grammar Ogata (2007). Although it adopts an original method, the music mechanism is fundamentally based on the music mechanism in an integrated narrative generation system.

The system proposed in this study uses images based on knowledge for each scene and expresses the stage by combining the images of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. KOSERUBE is a folktale-style story automatic generation system. The user selects a folktale story or character, automatically generates it based on the selected element in the system, and returns the generated animation to the user based on the generated story. KOSERUBE was used in the simulation system for the stage reproduction of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. Reproduction refers to the background, people, and music. The music was handwritten in some scenes using a free composition tool based on the score Kineie (2018). There are scenes in which there is no score; hence, existing music is used. We also reproduced a simple dance. Because the purpose of this system is to see the entire stage structure, it is a simple expression of dance. The marked part (Fig. 5) is modified to reproduce the stage performance structure with people, background (stage equipment), music (instrument and performer), verse, and dance.

As stated in Section 2.2, this study was based on a detailed analysis table of “stage performance structure.” As shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4, as its main components, they contain the characters, backgrounds (stage devices), music (instruments, performers, and genres), verses and lines, and the principal conceptual theme of each scene. In KOSERUBE, the words of the dance were entered into the text data and displayed, whereas the background and person were displayed as images. At the back, Nagauta singers and instrumentalists lined up in the same manner as they would on the actual stage. The person singing and performing in each scene is indicated by an arrow, and a spotlight is applied to yield a visually recognizable expression. In addition, the movement of Shirabyōshi Hanako’s dance was expressed.

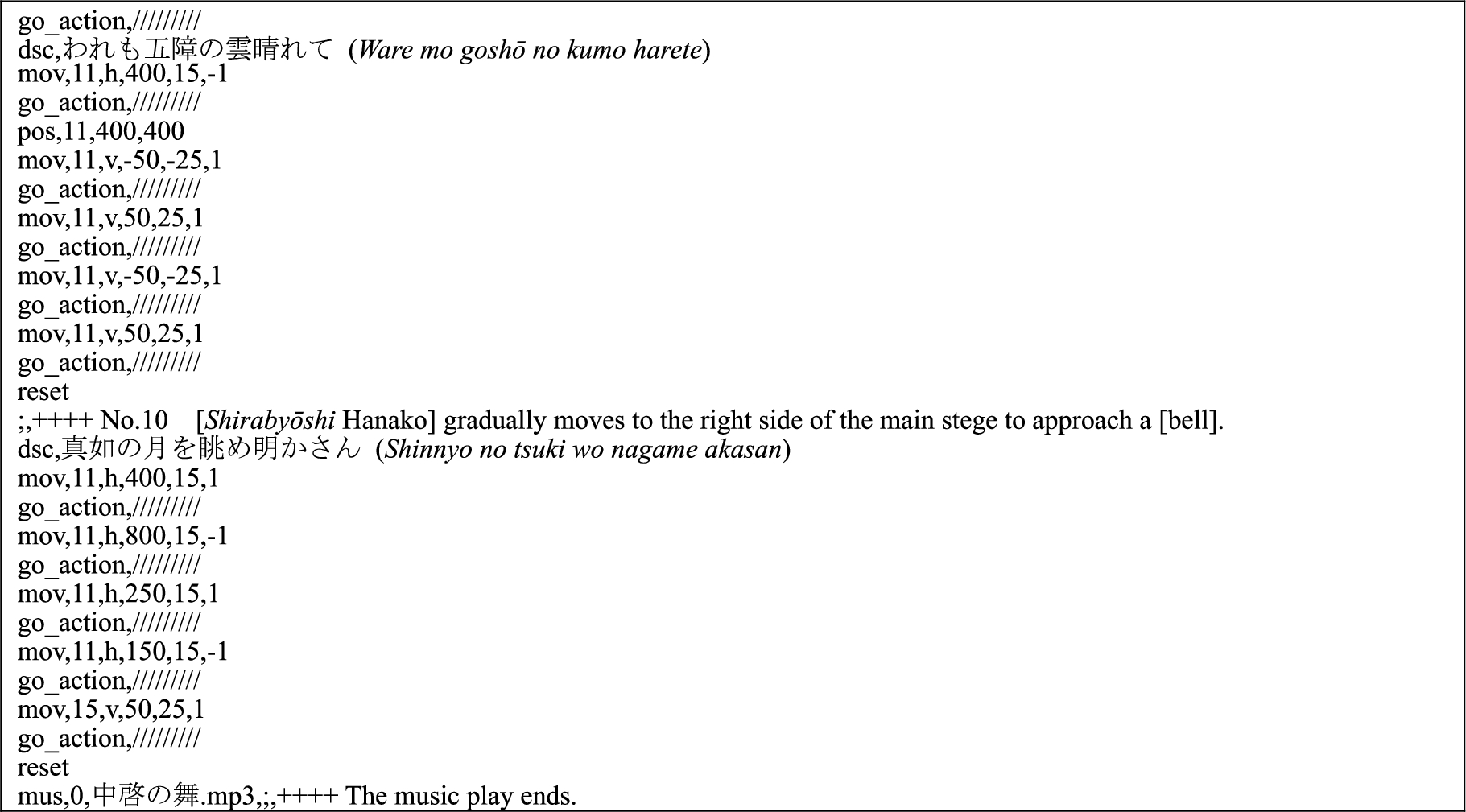

In the command file, the chapters on the dance to be displayed, reproduction timing of the music, switching of the background image enclosed with the picture database, etc., are described. Animation control is described later. In the proposed 2D representation system, the command uses limited elements of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji described in Tables 2, 3, and 4 as examples to generate the animation in each scene. This is a list of 11 scenes in the story of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and instructions that show the contents that express each scene. Figure 6 shows a part of Chūkei no Mai in Table 2, which generates a simple animation with a song “Kane ni urami ha kazukazu gozaru” [I hold a lot of grudges against the bell] based on the code. Table 6 lists the commands in the code shown in Fig. 6. The parts in [] represent the components used.

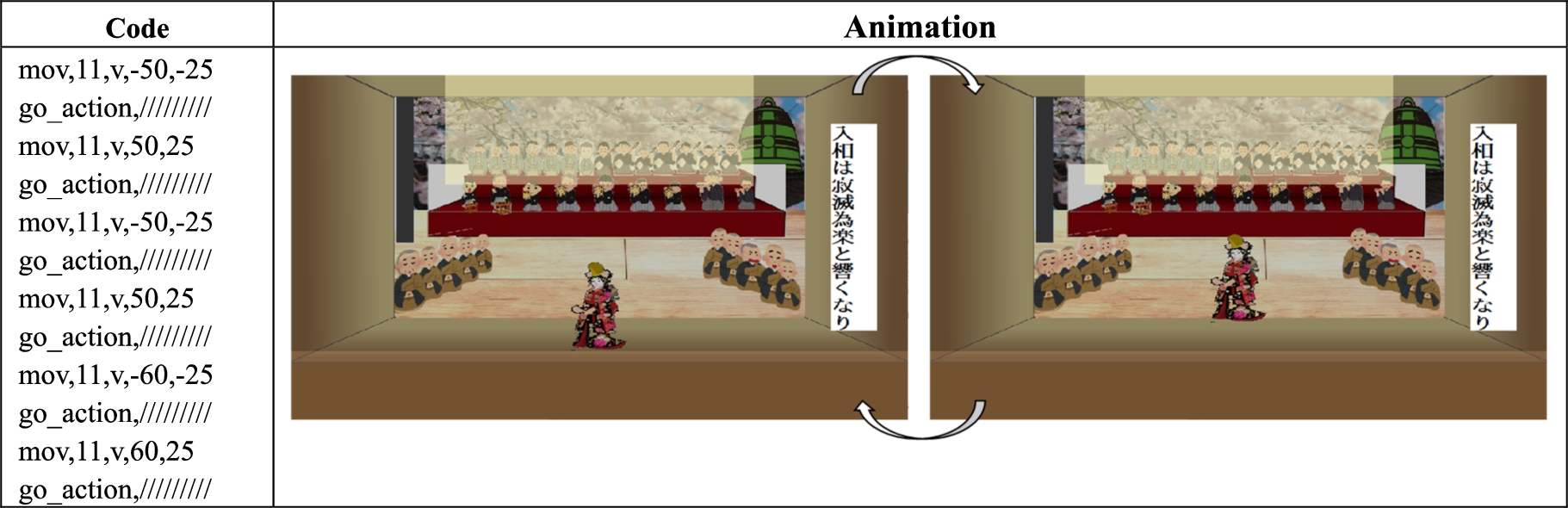

In KOSERUBE, the actual movement is simply expressed according to the code. In Fig. 7, the command “mov” is used. “mov, 11, v, −50, −25” represents move, character ID, vertical, movement distance, and speed, respectively, from the left. In the first line, the Shirabyōshi Hanako was moved vertically by a distance of 50 and a speed of 25. (The Shirabyōshi Hanako moved up from the current coordinates. Positive values move Shirabyōshi Hanako downward.) Overall, this implies bouncing Shirabyōshi Hanako three times. The right side depicts a screenshot of Chūkei no Mai’s dance (corresponding to Table 2). This illustrates the actual movement of the stage. On the actual stage, the actor moves his hand up and down on the spot. The objective of this research is not to pursue realistic human movements and express them but to visually reproduce the stage performance structure. Therefore, the dance was simplified in KOSERBE.

Additionally, KOSERUBE was expanded to include auditory elements, which were added from a musical score titled Music and Sound in Kabuki. Haikawa (2016) explains debayashi (Nagauta) and sound effects in Kabuki. This system used a music sequencer called “text music Sakura” (https://sakuramml.com/, last accessed on July 9, 2020). This tool can be used to compose and edit music by simply typing notes (C, D, E, etc.) in text form. In KOSERUBE, the auditory element is accompanied by an animation. Additionally, we created music using a free composer called “Wagakuhitosuji” by referring to the score in Shamisen Bunkafu Nagauta Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji by Kineie (2018). Unlike several composer tools, “Wagakuhitosuji” corresponds to the scale of Japanese music, rather than Western music, and allows composition on shamisen notation.

Fig. 6.

Part of the code entered.

Fig. 6.

(Continued.)

Table 6

Commands used in the code for 2D animation

| Command Name | Description Form | Meaning |

| ch_BG | ch_BG, FileName | Changes the background image on the main stage to the image defined by “FileName.” |

| Dcs | dsc, Text | Displays the character string designated by “Text” on the display. |

| Pos | pos, ID, X, Y | Displays the image by “ID” in the coordinate of “X” (width) and “Y” (height). |

| Mus | mus, 1 or 0, FileName | Plays (“1”) or stops (“0”) the musical file designated by “FileName.” |

| Mov | mov, ID, v or h, move, speed | The image of “ID,” executes the lateral movement (“h”) and vertical movement (“v”) according to the values of “speed.” |

| go_action | go_action, ///////// | Executes the movement of the image designated by the “move” command. |

| Reset | Reset | Returns the position of an image to the first state. |

| Spot | spot, lightID, X, Y | Displays the light by “lightID” in the position of “X” and “Y.” |

Fig. 7.

Example of a screenshot of the dance of “Chūkei no Mai”.

3.4.Associating between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji using 3D representation system

We have developed an experimental system that complements the 2D representation system of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji using the 3D representation system of the legend of Dōjōji (Kawai, Ono & Ogata, 2021a), representing the fragmented images of the legend of Dōjōji, which does not appear directly in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. We also considered various application systems for generating explanations as well as for education. Although the system can insert the animation of the legend of Dōjōji into the animation of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, our consideration of their association or correspondence was still insufficient. This study corresponds to the development of research on these associations. Additionally, the system proposed in this study is not only a complementation system but also a prototype toward more advanced goals, including more academic investigation and education systems of cultural heritage. Through the development of the survey and analysis of the association, we will view the possibilities of various systems beyond the complement system of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji.

3.4.1.3D representation system of the legend of Dōjōji

The system inserts the scene using the 3D representation system of the legend of Dōjōji shown in Table 1 into the given code and the stage reproduction of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji using a 2D animation system based on the knowledge base corresponding to its legend. For all 11 scenes that are reproduced on the stage, the results are returned to the user after scene insertion is completed.

An overview of the 3D representation system was prepared by changing the combination of images from KOSERUBE to a combination of 3D models. In particular, the input information into the 3D representation system is the list of modes to be used and the commands for the positioning and movement of the models. The system reads the list of models, interprets each command according to a sequential order, and outputs the results as a 3D animation. The commands listed in Table 7 are prepared.

The 3D model used was the one used in the “Miku Miku Dance” developed by Yu Higuchi (release date: February 24, 2008). Because this video is also intended to express the structure of the legendary scene of Dōjōji, the detailed movements are not reproduced, and they are symbolically expressed by combining 3D models. The final output video is explained in the next section.

Table 7

Commands and the definitions

| Command Name | Definition |

| Move | Described execution time, object, and the number of changes in x, y, and z for moving the object according to the values. |

| Setang | Describes execution time, object, and the number of changes in x, y, and z for turning the object according to the values. |

| Pose | Stops the object according to the inputted time. |

| Fire | Describes execution time, object, and switch for firing red light from the object’s mouth. |

| Sitdown | Describes the execution time and object for changing the object to a different model. |

| Setpos | Describes execution time, object, and the coordinates of x, y, and z for moving the object to the designated position. |

| End | Finishes the animation. |

3.4.2.Associating method between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji

The way the two stories come and go is expressed using two images, a 2D and a 3D one, with the mind change being key. The correspondence relationships that trigger the return are based on the method described in the following section. Specifically, we state the method of the association between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji.

As mentioned in Tables 2, 3, and 4 for Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the key terms for associating it with the events in the legend of Dōjōji shown in Table 1 are the “mind” and “action” of Shirabyōshi Hanako and lyrics. This time, the action includes Hanako’s facial expressions and gestures. The “mind” takes the values of P or N as the entire level and the value of “mind” in each scene is the same. Meanwhile, the “lyrics” and “action” action’ take the value P or N in each scene. In this study, we aim to emphasize and represent a scene that has a value different from the value of “mind” for emphasizing their contrast. In the “lyrics” and “action,” we aim to focus on the contrasting parts from the “mind.” However, when the values of “mind,” “lyrics,” and “action” in a scene are the same, one or more events of the legend of Dōjōji having the same value are selected.

From this description, the cases in which “mind” is P and N, and four types of combinations are produced. If “mind” is P [mind/P]:

mind/P, lyrics/N, action/N (2)

mind/P, lyrics/N, action/P (1)

mind/P, lyrics/P, action/N (1)

mind/P, lyrics/P, action/P (0)

mind/N, lyrics/P, action/P (2)

mind/N, lyrics/P, action/N (1)

mind/N, lyrics/N, action/P (1)

mind/N, lyrics/N, action/N (0)

The association with the scenes of the legend of Dōjōji is based on the above numbers (points). First, in the case of mind/P, the following association is conducted based on the following points:

2-point: The N+ scene of the legend of Dōjōji.

1-point: The N scene of the legend of Dōjōji.

0-point: The P+ or P scene of the legend of Dōjōji.

2-point: The P+ scene of the legend of Dōjōji.

1-point: The P scene of the legend of Dōjōji.

0-point: The N+ or N scene of the legend of Dōjōji.

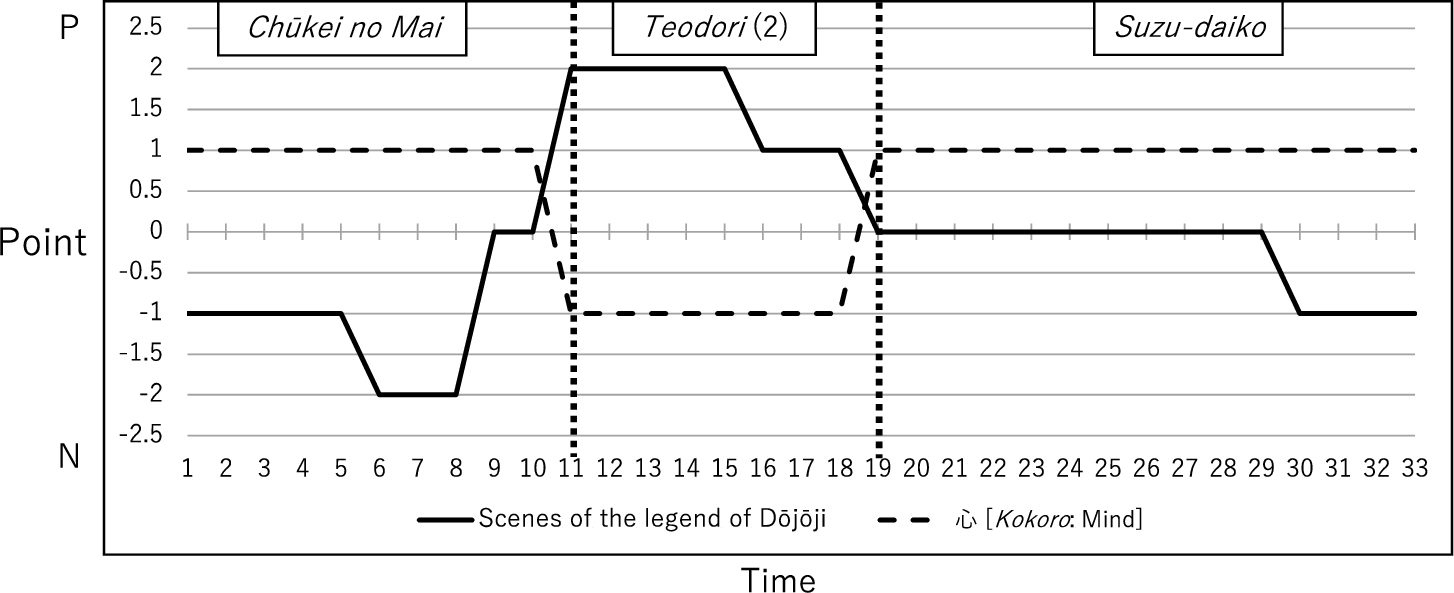

In this study, we associate Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji with the legend of Dōjōji. This method can be implemented in a system that contains the mechanism for moving to the legend of Dōjōji from the simulation system of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. A tentative idea of system implementation based on the above description is shown in Fig. 8: points of the events in the legend of Dōjōji associated when the “mind” is consistently 1(P) or −1(N) in “Chūkei no Mai,” “Teodori (2),” and “Suzu-daiko.” In many cases, contrasting events and scenes are mutually associated.

First, the timing of representing a scene of the legend of Dōjōji in the representation system of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji is determined by the user (experimentally, the system can execute the transition at any time without any user inputs). In cases of mind/P and mind/N, common processing was conducted. A corresponding scene is freely selected and displayed without managing, for example, the amount of display based on this point.

Fig. 8.

Associative patterns between the scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the events of the legend of Dōjōji.

4.Implementation and experiments

Based on the algorithm described in Section 3.4, we implemented a prototype system using Common Lisp, which associates the 2D representation system of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the 3D representation system of the legend of Dōjōji. When the user pushes the * key on the 2D system, the following algorithm is executed to represent 3D animation (while the 3D representation is executed, the 2D system stops):

(1) The system acquires the values of the P/N of mind, action, and lyrics from Tables 2, 3, and 4.

(2) The system calculates the point based on the value of P/N.

(3) The system refers to the 3D animation according to the calculation results in the order of the knowledge base. In addition, animations that were referred to once were not used.

(4) The system represents the selected 3D animation.

Table 9 shows the scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the scenes of the legend of Dōjōji that are associated with the experimental execution of the proposed system. (The underlined events of the legend of Dōjōji correspond to Figs 9, 10, and 11).

Table 8

Event list of the legend of Dōjōji by the values of P and N

| Values | Events in the legend of Dōjōji |

| P+ | Kiyohime, who lives in a private house, falls in love with Anchin at first sight. /That night, a reincarnated Anchin and Kiyohime appear in the old monk’s dreams. /Anchin and Kiyohime thank the old monk. |

| P | Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk head to Kumano on a pilgrimage. /Anchin and the old monk stay in a private house. /Anchin and the old monk leave Kumano. /The old monk and the monks of Dōjōji temple continue to chant the Lotus Sutra at Dōjōji temple. /Anchin and Kiyohime disappear from the dream. |

| N | Anchin lies to Kiyohime about visiting Kiyohime’s house. /Anchin and the old monk make a detour and return to their temple. /Kiyohime notices that Anchin lied. /Kiyohime is confined to her room. /Kiyohime cries. /Kiyohime crosses the Kirime River. /Kiyohime chases Anchin. /Kiyohime sits on a rock in Ueno. /Anchin and the old monk hear from a passerby that a snake is chasing them. /Anchin and the old monk run away. /Anchin and the old monk flee to Dōjōji temple. /The monks of Dōjōji temple hide Anchin in the bell of Dōjōji. /The snake arrives at Dōjōji temple. /The snake leaves. /The monks of Dōjōji temple look inside the bell. /That night, a high-ranking old monk has a dream. /In that dream, Anchin and Kiyohime appear as snakes. /Anchin and Kiyohime ask the old monk for salvation. |

| N+ | Kiyohime’s body turns into a snake. /Kiyohime spits fire. /Kiyohime’s body turns into a snake. /The snake spits fire on the bell. /The snake wraps around the bell where Anchin is hiding. /The monks of Dōjōji Temple find Anchin’s charred corpse. |

Table 9

Correspondence between Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji

| Scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji | Mind | Lyrics | Action | Events of the legend of Dōjōji |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Kane ni urami ha kazukazu gozaru (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Kiyohime crosses the Kirime River. (N) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Shoya no kane wo tsuku toki ha (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Kiyohime notices that Anchin lied. (N) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Shogyō-mujyō to hizbiku nari (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | The monks of Dōjōji Temple look inside the bell. (N) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Goya no kane wo tsuku toki ha (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Anchin and the old monk flee to Dōjōji Temple. (N) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Zesyō-meppō to hibiku nari (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Kiyohime is confined to her room. (N) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Jinjyō no hibiki ha shōmetsu-metsui (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Kiyohime spits fire. (N+) (Fig. 9) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Iriai ha jakumetsu-iraku to hibiku nari (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Anchin and the old monk make a detour and return to their temple. (N+) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Kiite odoroku hito mo nashi (N) | Shirabyōshi (P) | The monks of Dōjōji Temple find Anchin’s charred corpse. (N+) |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Ware mo gosyō no kumo harete (P) | Shirabyōshi (P) | That night, a reincarnated Anchin and Kiyohime appear in the old monk’s dreams. (P+) |

Table 9

(Continued)

| Scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji | Mind | Lyrics | Action | Events of the legend of Dōjōji |

| Chūkei no Mai | Girl (P) | Shin’nyo no tsuki wo nagame akasan (P) | Shirabyōshi (P) | Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk head to Kumano on a pilgrimage. (P) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Tada tanome (P) | Virgin (P) | That night, a reincarnated Anchin and Kiyohime appear in the old monk’s dreams. (P+) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Ujigami-sama ga kawaigarashansu (P) | Virgin (P) | Kiyohime, who lives in the private house, falls in love with Anchin at first sight. (P+) (Fig. 10) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Izumo no kamisama to yakusoku areba (P) | Virgin (P) | Anchin and Kiyohime thank the old monk. (P+) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Tsui nii-makura (P) | Virgin (P) | Kiyohime, who lives in the private house, falls in love with Anchin at first sight. (P+) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Sato ni koisureba ukiyo jyae (P) | Virgin (P) | Anchin and Kiyohime thank the old monk. (P+) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Fukai naka jya to iitatete (N) | Virgin (P) | Anchin and the old monk leave Kumano. (P) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Kocya-kocya-kocya yoi syubi de (N) | Virgin (P) | Anchin and Kiyohime disappear from the dream. (P) |

| Teodori (2) | Jealousy of the girl of Manago (N) | Nikutesashi hodo itoshirashi (N) | Virgin (P) | The old monk and the monks of Dōjōji Temple continue to chant the Lotus Sutra at Dojoji Temple. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Hana ni kokoro wo fukamigusa (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | The old monk and the monks of Dōjōji Temple continue to chant the Lotus Sutra at Dojoji Temple. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Sono ni iroyoku sakisomete (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk head to Kumano on a pilgrimage. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Beni wo sasuga shina yoku nari yoku (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk head to Kumano on a pilgrimage. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Aa sugata yasashiya shiorashiya (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin and the old monk stay in a private house. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Sassa soujaina (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Kiyohime, who lives in the private house, falls in love with Anchin at first sight. (P+) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Sassa soujaina (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin and the old monk stay in a private house. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Satsuki samidare (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | That night, a reincarnated Anchin and Kiyohime appear in the old monk’s dreams. (P+) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Saotome saotome taueuta (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin and Kiyohime thank the old monk. (P+) |

Table 9

(Continued)

| Scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji | Mind | Lyrics | Action | Events of the legend of Dōjōji |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Saotome saotome taueuta (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | The old monk and the monks of Dōjōji Temple continue to chant the Lotus Sutra at Dojoji Temple. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Suso ya tamoto wo nurashita sassa (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin, a young monk, and an old monk head to Kumano on a pilgrimage. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Hana no midaregami (P) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin and the old monk leave Kumano. (P) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Omoeba omoeba urameshiya tote (N) | Suzu-daiko (P) | The monks of Dōjōji Temple hide Anchin in the bell of Dōjōji. (N) (Fig. 11) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Ryūzu ni te wo kake (N) | Suzu-daiko (P) | The snake arrives at Dōjōji Temple. (N) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Tobuyo to mieshiga (N) | Suzu-daiko (P) | Anchin and the old monk flee to Dōjōji Temple. (N) |

| Suzu-daiko | Girl (P) | Hikikazuuitezo usenikeru (N) | Suzu-daiko (P) | That night, a high-ranking old monk has a dream. (N) |

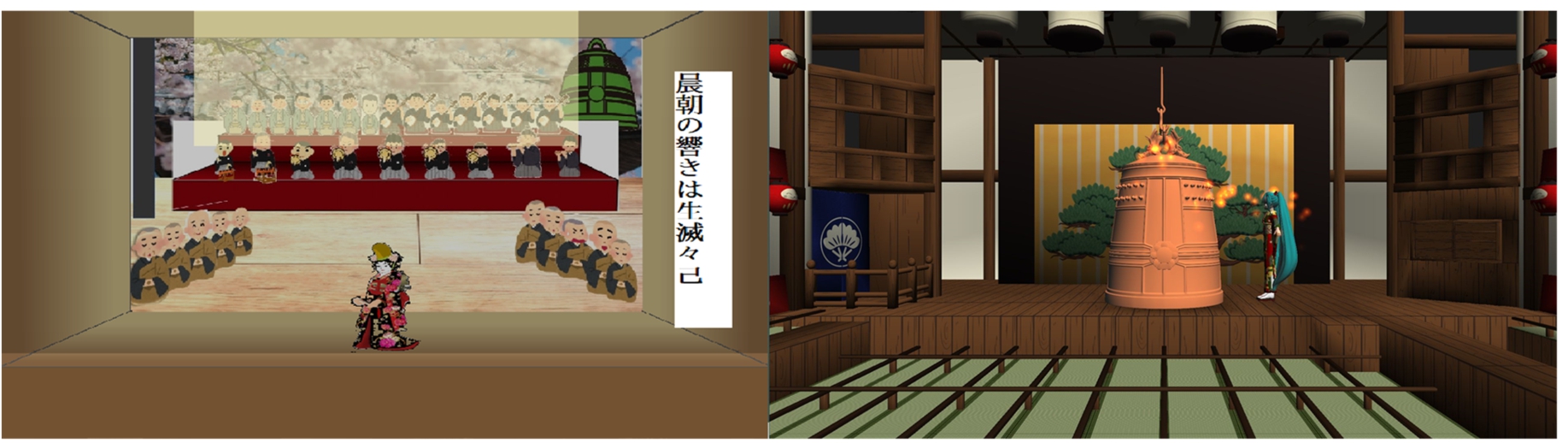

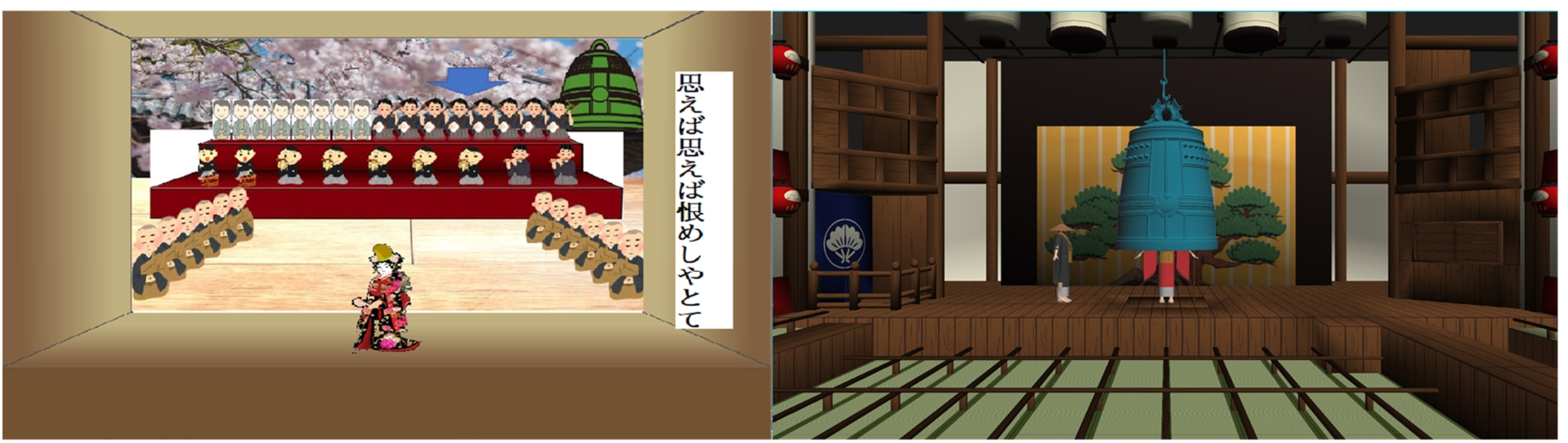

As examples of representation, Figs 9, 10, and 11 show a scene of the legend of Dōjōji that corresponds to a scene on the stage of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji.

In Fig. 9, the left shows a scene “Jinjō no hibiki ha shōmetsu metsui” (N) (the “lyrics”) in “Chūkei no Mai” Chukei no Mai’ of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. The “mind” is “girl” (P) and the “action” is “Shirabyōshi” (N). The right associated part of the legend of Dōjōji is the event of “Kiyohime spits fire” (N+). Next, the left scene of Fig. 10 is a scene of

Fig. 9.

Part of output video (1).

“Teodori (2)” of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji. The “lyrics” is “Ujigami-sama ga kawaigarashansu” (P), the “mind” is “virgin” (P), and the “action” is “Jealousy of the girl of Manago” (N). On the other hand, the right image shows the event of “Kiyohime, who lives in the private house, falls in love with Anchin at first sight” (P+) of the legend of Dōjōji. Finally, in Fig. 11, the left scene is the image of the “lyrics” “Omoeba urameshiya tote” (N), the “mind” is “girl” (P), and the “action” is “Suzu-daiko” (P). The right part shows the event of “The monks of Dōjōji Temple hide Anchin in the bell of Dōjōji” (N) of the legend of Dōjōji.

Fig. 10.

Part of output video (2).

Fig. 11.

Part of output video (3).

5.Problems and future works

There are five main problems to be addressed. We would like to examine these five points and connect them to promote further development of the system.

(1) In this study, we made Tables 2, 3, and 4 based only on the three scenes of “Chukei no Mai,” “Teodori (2),” and “Suzu-daiko” of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji to associate them with scenes of the legend of Dōjōji. In the future, we would like to make the tables of all the scenes of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji for the association with scenes of the legend of Dōjōji. Simultaneously, we will create 3D animations of all the scenes in the legend of Dōjōji. Moreover, we aim to improve the quality of animation using computer graphics (CG) technologies.

(2) The proposed prototype system does not consider the user interface, the role of an application system, etc. In the future, we aim to consider profitability as an application system from the user’s perspective to develop application systems based on the proposed system.

(3) Although Kawai, Ono, and Ogata (2020c) have developed a complementary system that adds various levels of explanations regarding Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the objective is to combine the proposed mechanism with the system described in this study. Additionally, for the complementary system, we presented the idea of a mechanism that can adjust the amount of explanation and its contents according to the user’s interests and concerns. We would like to introduce these ideas in future extensions of the proposed system.

(4) We consider how to use Kiyohime’s duality. Hanako, who appears in Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, has both negative and positive personalities related to love and sex, and her mind changes from scene to scene, presenting two appearances.

(5) We would like to develop an approach from a psychoanalytic perspective. As mentioned in Section 2.3, we extracted the concepts of nouns and verbs from the concept dictionary we developed Ogata (2015) and classified her two personalities. Hanako’s two-sided personality were mainly classified with dark scenes, represented by a glaring bell being negative, whereas beautiful and bright scenes being positive. These two personality changes are expressed by changing the overall color tone when expressing an image. For example, a negative scene is expressed by changing the color tone to bluish. We also believe that using duality, we can generate a story with the theme of extraordinary love.

Therefore, in the future, we would like to express a wider story by incorporating CGs and robots. This research explores a method that alternates between the scene of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and the legend of Dōjōji. The goal is to combine the generation of stories with CG and seamless expressions using robots. Based on the branching of the scenes, we consider a method in which many story scenes are generated in parallel using the story unit of the legend of Dōjōji.

Fig. 12.

Scene from Hanakurabe Senbonzakura (photographed by Takashi Ogata: August 1, 2019).

As mentioned in Section 1, storytelling robots can be a new form of narrative expression. For example, we propose a kamishibai (paper-play) robot. A kamishibai is a method of storytelling in which the narrator tells a story using pieces of paper with pictures representing the content of each scene. The narrator uses various gestures to draw the listener into the story. The storytelling by a kamishibai robot opens new possibilities. We also believe that the kamishibai robot can be applied to care and nursing care (e.g., Médecins Sans Frontières used the Kamishibai for AIDS prevention Campaign Enjelvin (2018)).

Additionally, Carillon Theatrical Society (https://www.ctsbathurst.com.au/) conducted musical theater productions and other performances, including animation.

6.Conclusion

We have investigated kabuki in the context of narrative generation based on information technologies, including artificial intelligence and cognitive science, as well as literary studies, such as narratology and literary theories. Moreover, kabuki dance work, Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, is pivotal to our narrative generation study of kabuki. Although we developed a novel 2D representation system that simulates the stage performance structure of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji based on its survey and analysis, this system was only a starting point for expanding the narrative generation study of kabuki and application systems using kabuki materials. As stated in INTRODUCTION, this study, aiming at diverse forms of narrative generation robots, develops a system that reflects the problems of love and sex through a cultural approach toward kabuki and related narrative works. In particular, we focused on the legend of Dōjōji as the background of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji and surveyed and analyzed both narratives and their relationships in detail. We concentrated on the positive and negative characteristics of the heroines common to these narratives, called Kiyohime or Shirabyōshi Hanako, to mutually associate these two narratives. These correspond to the contents of the first half of this study. The second half of this study describes the structure, design, implementation, and simulation results of a prototype system based on the above survey and analysis. This system aims to superimpose multiple stories utilizing Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, the heroine’s mind and action, and the lyrics sung or narrated on the stage.

In the future, by adding and extending the current deficient knowledge and CG animation, we will expand this prototype system to a completed system and explore various usages of the proposed mechanism and related surveys and analyses as application systems. Furthermore, we believe that it will become necessary for robots to tell stories for human entertainment, nursing, and long-term care. Therefore, we propose not only CG but also robots and to use the works of kabuki and Jōruri rather than Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji.

Notes

1 In medieval ages from ancient times of Japan, women wrote many narrative works. One of the most important topics was human love and sex or sexuality. Works depicting homosexuality in both women and men also exist. Japanese literary tradition includes the works of narrative, drama, and poetry that draw diverse types of loves and sexualities as a material trend.

2 Rather, it is the reason that Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji has been evaluated as one of the greatest works in all kabuki dance.

3 Although many recent stage performances of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji end at the scene of “Kaneiri,” the scene of “Oshimodoshi” after “Kaneiri” is rarely played.

4 However, snakes also have different symbolic meanings in Japan. Kondo (2012) shows that, while snakes have a nature that people dread, they are also a symbol of God and pacifists. For example, they may represent not only fear but also men and women and of peace. Thus, snakes do not always have a negative image. Additionally, Takano and Nishi (2007) explain the factors that make individual creatures anthropomorphic as written in a picture scroll, whereas the animals (mainly foxes, dogs, and rabbits) that appear in Chōjū-giga have anthropomorphic characteristics. It aims to clarify the characteristics of living things and their relationship with humans. For the details of the contents, please refer to the actual paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI, Grant No. 18K18509).

References

1 | Aristotle ((1997) ). Poetics (M. Heath, Trans.). London: Penguin Classics. |

2 | Dainihonkoku Hokekyō Genki ((1977) ). In M. Inoue and S. Ōsone (Collation Eds.), Ōjōden Hokegenki (pp. 43–219). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. |

3 | Dong, R., Chen, Y., Cai, D., Nakagawa, S., Higaki, T. & Asai, N. ((2020) ). Robot motion design using bunraku emotional expressions: Focusing on Jo-Ha-Kyū in sounds and movement. Advanced Robotics, 34: (5), 299–312. doi:10.1080/01691864.2019.1703811. |

4 | Enjelvin, G.D. (2018). Kamishibai: How the magical art of Japanese storytelling is being revived and promoting bilingualism. Published June 28, 2018, 10.47pm (AEST). Melbourne: The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/kamishibai-how-the-magical-art-of-japanese-storytelling-is-being-revived-and-promoting-bilingualism-97041. |

5 | Haikawa, M. ((2016) ). Music and Sound in Kabuki. Tokyo: Ongaku-no-tomo-sha. |

6 | Ham, J., Bokhorst, R., Cuijpers, R., van der Pol, D. & Cabibihan, J.-J. ((2011) ). Making robots persuasive: The influence of combining persuasive strategies (gazing and gestures) by a storytelling robot on its persuasive power. In B. Mutlu, C. Bartneck, J. Ham, V. Evers and T. Kanda (Eds.), Social Robotics (LNCS 7072) (pp. 71–83). Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-25504-5_8. |

7 | Harari, Y.N. ((2014) ). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. London: Harvill Secker. |

8 | Kawai, M. & Ogata, T. ((2019) ). An analysis of Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji for the generation of the staging structures of kabuki from narrative plots. In Proceedings of the 64th Special Interest Group on Language Sense Processing Engineering (pp. 25–61). Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. |

9 | Kawai, M. & Ogata, T. ((2020) ). Analyzing the stage performance structure of kabuki-dance “Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji”. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence (3D1-OS-22a-04). Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. |

10 | Kawai, M. & Ogata, T. ((2021) ). Towards a system that combines “Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji” and the legend of Dōjōji. In Proceedings of the 65th Special Interest Group on Language Sense Processing Engineering (pp. 13–24). Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. |

11 | Kawai, M., Ono, J. & Ogata, T. ((2020) a). Analyzing the stage performance structure of a kabuki-dance, Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, using an animation system. In E. Ishita, N.L.S. Pang and L. Zhou (Eds.), Digital Libraries at Times of Massive Societal Transition (LNCS 12504) (pp. 248–254). Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-64452-9_22. |

12 | Kawai, M., Ono, J. & Ogata, T. ((2020) b). Dual Story Generation Based on Love and Extreme Emotions. Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Love & Sex with Robots. Online, Dec. 8. |

13 | Kawai, M., Ono, J. & Ogata, T. ((2020) c). Explanation generation in a kabuki dance stage performing structure simulation system. In The 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (pp. 690–693). IEEE. doi:10.1109/CSCI51800.2020.00126. |

14 | Kawai, M., Ono, J. & Ogata, T. ((2021) a). Associating the mind, lyrics, and action in “Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji” with the Legend of Dōjōji. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of Japanese Congnitive Science Society (pp. 711–719). Japanese Congnitive Science Society. |

15 | Kawai, M., Ono, J. & Ogata, T. (in press). Analyzing the relationship between the Legend of Dōjōji and the Kabuki-dance Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji to develop prototyping systems. Journal of Artificial Life, Networks and Robotics., 8: (3), (in December, 2021). |

16 | Kheng, K., Dag, S., Kerstin, D. & Michael, W. ((2020) ). A narrative approach to human-robot interaction prototyping for companion robots. Journal of Behavioural Robotics, 11: (1), 66–85. doi:10.1515/pjbr-2020-0003. |

17 | Kineie, Y.I.V. ((2018) ). Nagauta Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji: Shamisen Bunkafu (75th ed.). Tokyo: Hōgakusha. (Original book published 1952). |

18 | Kobayashi, S. (2018). Approach to choreography “Kiyohime”: A comparative study of japanese traditional dance and western ballet for female. (No. 500001080615) [Doctoral dissertation, Osaka University of Arts. National Diet Library. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11101035. |

19 | Kondo, Y. ((2012) ). The role of the snakes in old tales and myths: A snake that symbolizes wisdom, life, and the opposite sex. HABITUS, 16: , 1–25. doi:10.15027/33769. |

20 | Konjaku Monogatari-shū ((1999) ). In K. Mabuchi, F. Kunisaki and T. Konno (Eds.), Konjaku Monogatari-shū, Tokyo: Shōgakukan (Vol. 1: ). |