Designing an Alternative, Community Integrated Model of Residential Aged Care for People Living with Dementia: Nominal Group Technique and Thematic Analysis

Abstract

Background:

Small-scale models of dementia care are a potential solution to deinstitutionalize residential aged care and have been associated with improved resident outcomes, including quality of life and reduced hospitalizations for people living with dementia.

Objective:

This study aimed to generate strategies and ideas on how homes for people living with dementia in a village setting within a suburban community, could be designed and function without external boundaries. In particular, how could residents of the village and members of the surrounding community access and engage safely and equitably so that interpersonal connections might be fostered?

Methods:

Twenty-one participants provided an idea for discussion at three Nominal Group Technique workshops, including people living with dementia, carers or former carers, academics, researchers, and clinicians. Discussion and ranking of ideas were facilitated in each workshop, and qualitative data were analyzed thematically.

Results:

All three workshops highlighted the importance of a surrounding community invested in the village; education and dementia awareness training for staff, families, services, and the community; and the necessity for adequately and appropriately trained staff. An appropriate mission, vision, and values of the organization providing care were deemed essential to facilitate an inclusive culture that promotes dignity of risk and meaningful activities.

Conclusion:

These principles can be used to develop an improved model of residential aged care for people living with dementia. In particular, inclusivity, enablement, and dignity of risk are essential principles for residents to live meaningful lives free from stigma in a village without external boundaries.

INTRODUCTION

Nationally and internationally, there are strong social pressures to deinstitutionalize residential care for people living with dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease [1]. Therefore, there is a focus on having people who have cause to draw on this high level of care residing in homes in the community [1]. These may be single dwellings or a cluster of homes in a village setting. In Australia, small-scale models of residential aged care have received greater attention in light of findings by the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. The Royal Commission was established in 2018 in response to increased public awareness of abuse and neglect of residents in aged care homes. The Commission identified multiple serious failures in the Australian aged care system, with the final Report, released in 2021, making 148 recommendations for reform including that the Australian Government support residential aged care providers to redesign the built environment and modify care models to enable them to “provide small-scale congregate living which facilitates the small household model of care” [2]. This has the potential to improve quality of life and health outcomes for people living with dementia who require more personalized care and support [1, 3–5]. These small-scale dementia care models often sit within community settings and aim to integrate residents with, rather than segregate them from, the surrounding neighborhood.

Small-scale dementia care homes typically accommodate six to fifteen people, consider residents’ personal preferences and privacy, recruit staff willing to get to know residents and engage in typical home activities such as preparing meals together, all attributes that may not be achievable in other environments [1]. Small-scale environments can increase meaningful engagement in everyday activities, access to the outdoors, quality of life, social interaction, staff satisfaction, and resident-rated quality of care while also lowering hospitalization and emergency department presentations [1, 3–6]. Types of small-scale environments vary, from clustered homes within larger organizations to stand-alone houses in the community. Currently, small-scale care models in Australia focus on social engagement, relationship-building, and person-centered care, concepts that aim to maintain the dignity and respect of residents [5, 7, 8]. Small-scale dementia care can contribute to physical, cognitive, psychological, and social well-being and are often described as ‘enabling’ [4, 9]. ‘Enabling’ care environments aim to minimize disability, be flexible in care, and support the individual to engage in meaningful activities. There may also be reduced use of psychotropic medications [4, 7, 10].

The underlying principle is to enable people living with dementia to maximize their ability to live an autonomous lifestyle that supports their strengths, unique needs and preferences, and provides support from their family, friends, the care team and the wider community [7, 10]. The home and village environment are designed to be familiar to residents, supporting them to function optimally and maintain their capabilities. Residents are, therefore, less likely to feel trapped, imprisoned, or lost [10]. The homes are typically surrounded by gardens and accessible services such as a grocery store, a hairdresser, a café, and an early learning center. Typical design elements include appropriate orientation aids, gardens, water features, picnic areas, and environmental safety features both within homes and in the external setting. Safety features may include no steps and inconspicuous gates, doors, or fences that allow for some autonomy but reduce risk of harm.

This embraces the principle of ‘dignity of risk’, whereby people (of any level of cognitive impairment) can make choices and accept risks of potential consequences [11]. This challenges current paradigms where safety is often paramount but to the potential detriment of people living meaningful lives with self-expression of identity and choice. However, because most of these villages are ‘gated’, seeking a balance between freedom of choice and protection from harm, they have been challenged as still being restrictive, segregating people living with dementia from the rest of the community [12].

There is not yet enough evidence to convince many organizations to completely shift to small-scale models, with a Cochrane review finding only six studies of low quality [1]. There are few examples of genuine integration of residential aged care homes for people living with dementia that are truly embedded into the community. Similarly, public involvement in developing and implementing these homes is not commonplace [12]. In particular, how to manage the levels of ‘openness’ and accessibility to services and other facilities in terms of locked doors, gates, and external boundaries in such care homes remains unclear [12]. In Australia, there are no villages designed to enable people living with dementia and located in a community without external boundaries, which would allow residents to be more integrated into the surrounding community as part of their daily lives.

The current study aims to assist in the proposed development of a purpose-built village named ‘The Neighbourhood, Canberra’ (TNC), which will be designed for people living with dementia in the greater Australian Capital Territory (ACT) region. The study aims to generate strategies and ideas on how a village could be co-designed to function without external boundaries, so that residents and community members can engage safely and equitably in all aspects of the open village.

METHODS

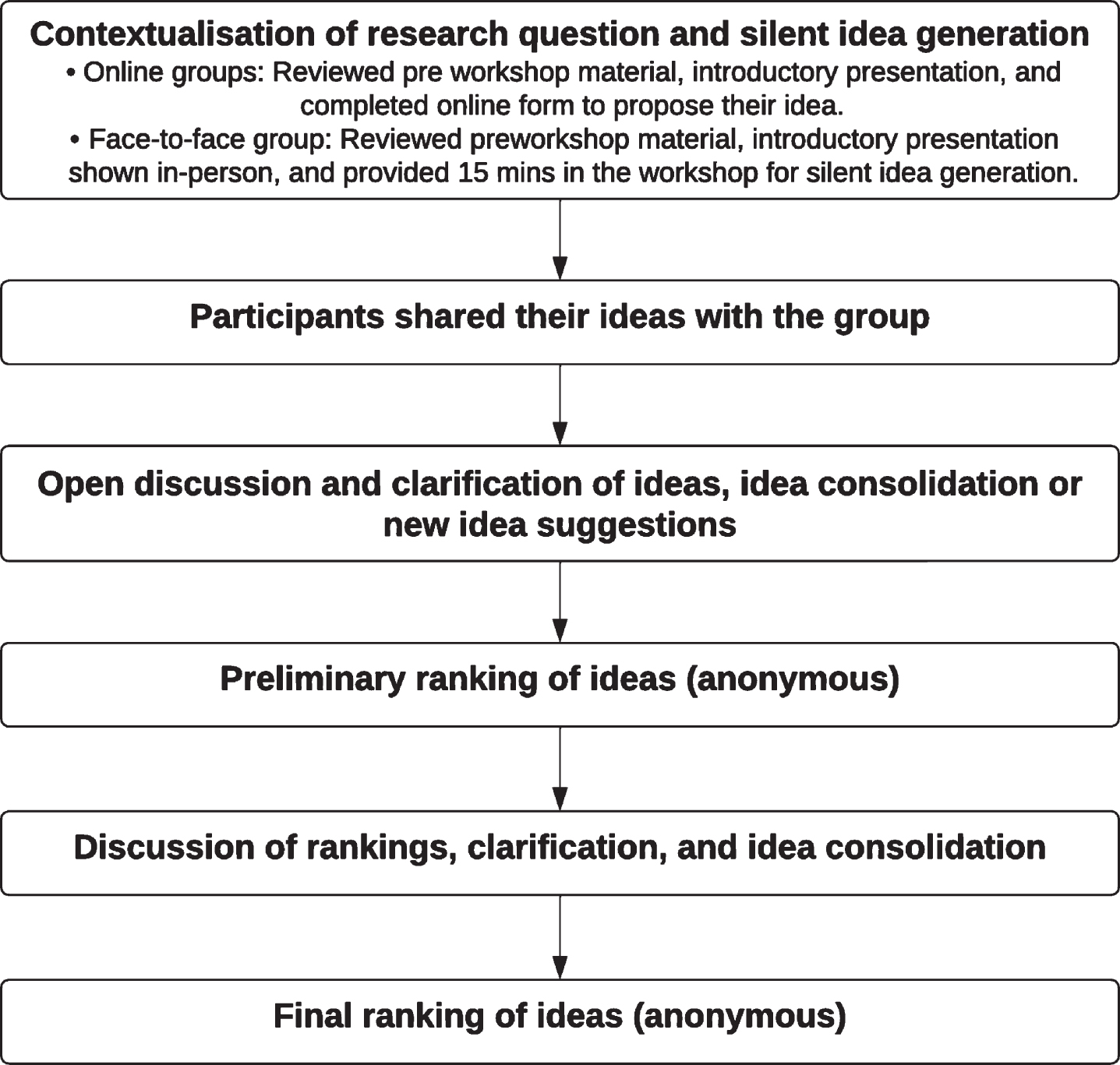

This study used a collaborative process named Nominal Group Technique (NGT) [13, 14]. This technique is commonly used to explore healthcare priorities and strategic problems to generate and develop appropriate and innovative ideas. NGT generates stakeholder perspectives in group discussions where participants have a common interest and the knowledge and experience to contribute. Each participant is given an equal opportunity to present their idea independently, and other group members are encouraged to respectfully ask questions if their idea requires clarification (Fig. 1). This process aims to prevent the domination of the discussion by one group member and encourages all members to participate and thus is constructive for use with members of the public alongside professional experts [14]. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Canberra Human Ethics Research Committee (HREC 2022.11728).

Fig. 1

Nominal Group Technique process.

Study context

The current study aims to assist in the proposed development of a purpose-built village designed for people living with dementia in the greater Australian Capital Territory (ACT) region (https://www.theneighbourhoodcanberra.com.au/). TNC is a not-for-profit association consisting of local volunteers interested in dementia care and with experience caring for people living with dementia. A unique aspect of TNC is that it aims to foster genuine human connection with the community in which it is located. By having an authentic connection to the community and encouraging intergenerational connections, TNC has a goal of setting a foundation for a nurturing, loving and meaningful life for residents. TNC is proposed to have 15 small-scale residential homes of six people per home in a village setting, with services for residents and the local community, including a café, shops, childcare center, health facilities, and other on-site services. An aspiration of TNC is to be an open village, without external boundaries, and a built environment designed to maximize permeability between the homes, services, and local community. Collaborating with an innovative and forward-thinking aged care provider is essential for TNC to realize their vision. It is anticipated that the outcomes of the current study will support the establishment and co-design of a village for people living with dementia who have cause to draw on a high level of care embedded in the local community.

Participants

An expert panel was convened, including people living with dementia, carers or former carers of people living with dementia, people working in aged care, and academics with expertise in gerontology and clinical experience. A purposive sample was identified, and individuals were contacted and invited to participate by email. The sampling aimed to recruit people who would be familiar with, or able to understand the concept of, small-scale and village-style dementia care and who would have well-informed ideas and suggestions to guide the principles, practice, and design. All participants provided written consent.

Procedure

NGT recommends no more than 9 people per group, therefore, multiple workshops were planned to ensure a range of viewpoints across and between stakeholders. Two online and one face-to-face workshop were offered to participants. The allocation to groups was conducted based on the preferences and availability of participants. Conducting NGT workshops online has become more common during the COVID-19 pandemic [15], and enabled people living outside the ACT region to participate. This was also useful for people in the ACT region who had scheduling conflicts with the face-to-face workshop.

Participants were provided with an information guide prior to the scheduled workshops, which presented background information with a two-page summary of currently available evidence, the aim of the workshops, a brief description of the NGT process, and recommended additional reading. The information guide was designed to be accessible to all participants and was written in plain language. A visual summary was also provided in the form of a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation, which included orientation to the project, examples of villages for people with dementia, an introduction to TNC, and an explanation and contextualization of the research question and NGT process.

Each group was facilitated by an experienced occupational therapy clinician and two academics familiar with the NGT process and with experience working in and researching dementia care. The facilitators had met most of the group members prior to the interview in a professional capacity, and the participants were aware of the facilitators’ roles in the research project. The question proposed to all groups was:

What needs to be in place to ensure that people living with dementia can engage safely and equitably in all aspects of the Neighbourhood?

Participants were asked to consider their idea further using prompts as displayed in Table 1. There were slight differences between the face-to-face and online groups, with the online groups being asked to do additional preparation in the form of watching the Microsoft PowerPoint presentation to reduce the time spent online (Fig. 1). During each workshop, additional time, rephrasing of questions, and direct time for quieter members were used to support the diversity of experience of group members and their communication needs. The NGT methodology was used to minimize the impact of power imbalances by giving equal time opportunity to express their views. Moreover, each participant was introduced by a researcher without reference to qualifications. All researchers, clinicians, and service providers who participated were experienced in working with people living with dementia and accustomed to creating equitable and relaxed forums for human-to-human interaction. Each workshop was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy by a facilitator. Each online workshop lasted 90 min, and the face-to-face workshop lasted three hours. Participants living with dementia received support from their carer or other participants when needed. The facilitators took notes during each workshop.

Table 1

Guide for silent idea generation [39]

| What needs to be in place to ensure that people living with dementia can engage safely and equitably in all aspects of the Neighbourhood? *For example, café, shops, library, restaurant, fitness center, childcare center, classrooms, hairdresser | |

| Name your idea | My idea is called... |

| Explain your idea | My idea is... |

| Summarize the benefits | My idea would be good because... |

| Identify the obstacles | The main obstacles to be overcome before the idea would work would be... |

Data analysis (NGT)

Each participant, in turn, presented their preliminary ideas to their group, and a record of these was captured. Discussion ensued, and the group collated, debated, and refined the ideas with assistance from facilitators. Common or similar ideas were formed into combined suggestions based on consensus. Preliminary voting was used to rank the original ideas and to facilitate further discussion before final voting within each workshop group. Subsequently, a final list of three ranked ideas were agreed upon in each workshop. There are no agreed-upon levels of acceptable consensus for NGTs, and pragmatically, a consensus level of two-thirds (or 66%) was considered appropriate [16, 17].

Data analysis (thematic analysis)

The ideas from each participant, final ideas, and transcripts were analyzed using a reflexive thematic approach. The analysis used the six-phase process for data engagement, coding, and theme development, as Braun and Clarke (2020) described. This included three researchers (ND, HH, and SI) undertaking data familiarization, systematic data coding, generation of initial themes from coded data, developing and reviewing themes, refining, defining and naming themes, and writing the report [18]. Each participant was sent a summary of the results of the workshops and a preliminary thematic analysis for member checking. Comments were invited on whether the participants felt that the representation of the ideas from their workshop were accurate. To ensure best practice for qualitative research, we adhered to the “Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)” reporting guidelines [19].

RESULTS

The purposive sampling process included 30 people. In total, 22 people agreed to participate. Five people did not participate due to non-response, and two were not available/declined. One person agreed to participate but withdrew due to unforeseen circumstances, leaving 21 participants (70%). Three NGT groups were scheduled. Participants located in the ACT region were invited to attend the face-to-face NGT workshop, while those in other cities or unable to attend the face-to-face NGT workshop participated via Zoom. Some ACT participants chose to participate via Zoom. All participants are involved in either aged care and/or dementia research, providing care and support services for people living with dementia, or having lived experience or caring for a person with dementia. Consensus from each group is presented prior to presenting the themes from the qualitative analysis of statements and workshop transcripts. Participant roles and codes for the quotes featured in the thematic analysis are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Participants of NGT Workshops

| Workshop 1 (Online) | Workshop 2 (Face-to-face) | Workshop 3 (Online) | ||||||

| Code | Role | Location | Code | Role | Location | Code | Role | Location |

| R1 | Researcher/Psychologist | NSW | S1 | Service Provider/Nurse | ACT | R6 | Researcher | TAS |

| C1 | Carer | TAS | P1 | Person with Dementia | ACT | R7 | Researcher/Occupational Therapist | NSW |

| R2 | Researcher/Geriatrician | NSW | S2 | Service Provider | ACT | R8 | Researcher | NSW |

| R3 | Researcher/Aged Care | NSW | C2 | Carer | ACT | C4 | Carer | QLD |

| R4 | Researcher | ACT | P2 | Person with Dementia | ACT | P3 | Person with Dementia | QLD |

| R5 | Researcher | UK | C3 | Carer | ACT | S4 | Service Provider | ACT |

| S3 | Service Provider | ACT | R9 | Researcher/Nurse | ACT | |||

| L1 | Local Politician | ACT | ||||||

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; NSW, New South Wales; QLD, Queensland; TAS, Tasmania; UK, United Kingdom.

Consensus from the NGT workshop

The original ideas generated by participants were about increasing dementia awareness and education in the local community (n = 6); an inclusive and flexible culture that is deinstitutionalized (n = 4); staffing and care that encourages meaningful activities and engagement (n = 3); a support and training framework for all people associated with the village (n = 1); placemaking/creating inclusive public spaces valued by the people who use them (n = 1); using technology to make shared memories with family (n = 1); a focus on intergenerational relationships (n = 1); freedom and safety with help from technology (n = 1); balancing safety and a human rights-based approach (n = 1); a safe and navigable physical environment (n = 1), and community gardens (n = 1).

Following discussion and preliminary and final voting, all three groups highlighted the importance of the community surrounding the village as critical to its success. Education, culture, and staffing were also common ideas considered and discussed by each group, with some similarities and differences. The top three ideas from each group are presented in Table 3. The similarity between the final ideas was noted by several participants in their email responses to the preliminary report indicating resonance. In particular, this related to the need for the right number of staff with an appropriate level of education to support the culture needed for a village for people living with dementia without an external boundary. This was raised in different ways but with similar meanings and words used across workshops by participants. Many participants were adamant that without appropriate staffing, targeted education, and the right culture, the vision could not be achieved.

Table 3

Top three consensus ideas

| Idea | Description | |

| Top three ideas – NGT 1 | ||

| 1 | Train the community | Community members and businesses need to be trained on how to engage with people living with dementia and understand their complexities. Genuine care and empathy from the community needs to be fostered – not only from staff and families. This will require an embedded communication strategy within the local community. |

| 2 | Inclusive culture and environment | Set norms for inclusivity, respect, and tolerance for everyone within the community. There should be communal spaces for everyone, and potential environmental triggers should be considered (e.g., music, lighting, ambiance) to create a safe, respectful and peaceful vibe. The physical environment should enable intergenerational relationships and stimulate memories and learning through different mediums including art, music, and technology. |

| 3 | Staff and the context of care | Staff should be supported to create and enable a relaxed environment and model of care, and to enable dignity of risk. It is essential this is supported by technology and the physical environment. |

| Top three ideas – NGT 2 | ||

| 1 | The culture | The culture of care needs to be enabling for staff. There should be flexible and appropriate staffing ratios (depending on the needs of the person). It is essential to find the right staff, who want to be part of a family, while providing person-centered care. |

| 2 | Support &training framework | A framework of support should be in place for all stakeholders to ensure residents have dignity of risk and choice. Hubs of support should be in place to engage with internal and external stakeholders to foster a collaborative, inclusive culture, with education at various levels. |

| 3 | Whole community culture | All people in the community (staff, people working at facilities, surrounding communities) should be educated on dementia so that the village can meet the needs of all – no need for fear. The built environment must be safe and accessible to all users and appeal to people in the community. The design of the grounds should promote good health, social interaction, and good nutrition [community gardens – the harvest can be used by on-site facilities] and address the needs of culturally diverse groups. |

| Top three ideas – NGT 3 | ||

| 1 | Dementia friends in the community | Integration with the community will only be achieved with acceptance of the idea by the community. This will require a long-term systematic approach that includes 1) information and engagement with the community, 2) education and resources on dementia and person-centered care, and 3) Community education about the model of care and potential triggers for behavior. Along with safety features built into the environment, having a dementia friendly community will help balance safety along with human rights and legal responsibilities. |

| 2 | Staffing for meaningful and accessible engagement | Workforce must be resourced to “go with the flow” of the person with dementia and to facilitate choices and tailored experiences that suit their skills, interests, communication styles, and mood. This requires a skilled and nuanced approach. More than “dementia aware” or “dementia friendly”, it should be “dementia enabling”. This approach should include jobs within the facilities for people living with dementia to provide a sense of purpose and reduce social isolation. |

| 3 | Deinstitutionalize staff and family | Education, guidelines, and policies need to be in place to support deinstitutionalization – with an overarching goal of promoting dignity of risk and a person-centered care approach that can overcome behavioral and safety concerns of staff and families. |

Thematic analysis

To provide a more nuanced analysis of the discourse when deciding consensus statements, a thematic analysis of the three workshop transcripts was performed to provide insights into the thoughts, opinions, and experiences of participants. The main themes were 1) A surrounding community that is invested in the village; 2) Education of all people at all levels of the village community; 3) Care staff who promote an enabling person-centered care environment; 4) The organizational mission, vision and values promote an inclusive culture; 5) The village should allow residents to engage in meaningful activities, and 6) The built environment is designed to enable maximum engagement.

Theme 1: A surrounding community that is invested in the village

This theme had strong support during the discussion across all three groups and is aligned with the top-ranked idea in two NGT groups: “Train the community” and “Dementia friends in the community”. One participant summarized this theme:

“I think the local community is going to require some preparation, and I think this will require quite a lot of investment of time and resources. ...But, what we have not yet done anywhere, to the best of my knowledge, is really get the surrounding community to fully embrace and accept and almost rejoice in the fact that within the community, there are a group of people who happen to have dementia” (R8).

Participants expressed that early and ongoing communication and consultation with the local community was essential to maximize their engagement and acceptance of the village. It is “essential to do the groundwork to ensure that we do get buy-in from everyone” (R2). Communication should occur before establishment, which would allow the local community members to have their concerns addressed. One participant suggested to “set up some forums so that the neighborhood can be fully informed about the nature of the facility itself and the actual size of it and what is going to be the concrete details” (R8).

Another participant (R5) stated that communicating with the surrounding local community also provided an opportunity to “talk about the values and purpose of the [village]”. Participants raised the need to market the village and its facilities (shops and garden areas) to the local community: “it is all about marketing what we’ve got on-site as well and how well we can integrate that” (S2) to foster their engagement.

Defining the local community and understanding their needs was also seen as an important consideration of successful marketing (R1).

Theme 2: Education of all people at every level of the village and community

Several different groups of people will engage in the proposed open village for people living with dementia, including the residents, families, staff, businesses, and the surrounding community. The level of knowledge of dementia and the subsequent learning needs of the different groups of people will be divergent and need to be considered: “It’s not a given that all people think the same...I think basic training would be central to all stakeholders” (S3).

Education was seen as an essential way to address all the needs of the different groups and a way to: “emphasize that people with dementia can still have choice about what they want to do...and to promote basically that idea of dignity of risk” (R6).

“There is big training and little training and you’ve got to kind of like, understand the motivators of people using those spaces, all the different groups and ... understand the concerns and how much training they want to do...all different types of training” (R1).

While directing people towards existing formal educational resources was considered valuable, this could also be about general media or posters within the community, for example, guides to communication aids, environmental cues, and vignettes about the people living in the village.

Subtheme 1: The local community

Participants thought that education and training in the local community could promote the benefits of a dementia-enabling village and contribute to the de-stigmatization of aging and dementia. In that way, the village is an opportunity to educate the population. For example:

“...people still have a very narrow mind of what [dementia] is and [they think] that it’s just forgetting things and repeating things. They don’t seem to understand, a lot of the complexities, change of personalities, just even...the way to communicate with somebody [with dementia], in a language that they can relate to” (C1).

This education would need to be an ongoing open dialogue between the aged care provider and the local community for “disseminating information...about what that experience is like, what dementia is like” (R3). One participant stated that using the lived experience of a person with dementia in the form of vignettes may help educate the local community and “alleviate or tackle” (R5) stigma.

Participants discussed utilizing established programs, such as the Dementia Australia ‘Dementia Friendly Communities’ initiative, whereby community members, alliances, and organizations can sign up online and commit themselves to the campaign. “If we could set the goal of every third person in the immediate neighborhood, being an active dementia friend, I think it’d be a very high success” (R8). “Everybody has to do the University of Tasmania Dementia courses” (S1). “Let’s try to use the resources and skills which we have” (R8). However, education in the local community may be challenging: “...some of the obstacles might be time or cost of implementing training and whether the people are willing to participate” (C1).

The participants thought that many community members would want to contribute in these ways, as well as recognition that many will not be interested, ambivalent, or actively hostile – ‘not in my backyard’.

Subtheme 2: Care and support staff

Unsurprisingly, education about dementia for care and support staff was considered necessary, but of particular interest was the focus on aspects such as dignity of risk, enabling and empowering people living with dementia to make choices, well-developed communication skills, and a person-centered model of care.

“In terms of you hearing words like dignity and genuine connection, there’s a need for training around that and...I think attracting the right people” (S3).

“[S]killed staff in having the abilities and communication skills and rapport development, and knowing the people to be able to support that engagement, whether that’s...employment and the remuneration or working with the childcare workers, because all of all of it needs to be actually staffed” (R9).

Staff who may be used to providing task-driven, time-based care may have difficulty adapting to a new way of doing things where residents are provided choices around personal hygiene, meals, activities, and going out into the community. Therefore, selecting the ‘right’ staff, who have a willingness to learn and be adaptable to ongoing training will be critical to retaining staff.

Subtheme 3: Families

Educating the family of residents about dementia and dignity of risk was also discussed, recognizing that family members could be worried about the safety for residents living in a village without external boundaries.

“Train families about what it’s like to live with a dementia...so that they won’t be worried about that, they will know. I would hope that the staff and the family are dementia friendly as well” (P3).

When discussing the open village concept, one participant stated that “obstacles would be possibly family and I’d be concerned that this was a reckless thing to do, unless there were safeguards” (C2). Participant R6 suggested that many family members would be expecting the ‘safety’ of a traditional aged care setting and may need education about the principles of ‘dignity of risk’ and awareness of consequences.

Subtheme 4: Business stakeholders and services

Along with the other groups in the village, it was felt important to “not just talk[ing] about support and training staff and the model of care, but also support and training to the other stakeholders” (S3), including those that decide to set up a business in the village. This is because they will have regular interaction with the people living with dementia utilizing the different facilities and will be making decisions that affect the ‘dementia-friendliness’ of the space.

“Who’s going to be using this communal space...think about all the needs of those groups of people separately in terms of how much education and support they need” (R1).

“If this community [village] is going to have small businesses around, then they need to understand what might happen if people with dementia come in and they get confused” (C1).

Providing knowledge about dementia, how to communicate with a person with dementia, and how to manage any issues of concern would be necessary for successful engagement between services accessible to the community and residents.

Theme 3: The organizational mission, vision and values promote an inclusive culture

Important to the operation of this village is a culture based on inclusivity and enablement of choices for people living with dementia that acknowledges dignity of risk, respect, and tolerance, and embraces an intergenerational philosophy (S1, S2).

Subtheme 1: Culture of the organization

The culture of the organization operating the village should enable the vision and purpose of the village to be realized. This culture needs to be embedded in the organization at establishment of the village and requires a radical change in thinking from pre-existing cultures that may be present in other aged care contexts.

“There’s a tremendous amount of work that’s been done in disability in this area, you know, the great deinstitutionalization and normalization of disability in the community. So, I guess it is...a piece of work around education to get both staff and family...more attuned to not working like an institutional all the time.” (R6)

This organizational culture can be developed through the organizational mission, vision and values, policies, and procedures.

“At the risk of it ending up like any other residential aged care home, if we don’t set the mission and vision and philosophy now, and then do 360 feedback and constant monitoring...like you know, not to say, ‘here’s the culture, let’s go!’. You’re going to have to monitor that for the rest of the time.” (S1)

“We need to set an inclusive culture in The Neighbourhood and have ways to actively nudge people towards the culture. That is, we need to set norms for inclusivity and respect and helpfulness and tolerance for everyone who was part of the community” (R1).

One participant thought, “it’s important for everyone to feel a sense of place, a sense of ownership.” (R5). This included the residents, the family, the care and support staff, the local community, and the business stakeholders:

“So not just the staff of the homes, but also your hairdresser, your supermarket, your bar. So, they’ve all got it, but we’ve all got to be on the same page.” (S1)

However, one participant believed a major challenge is “to get organizations to become dementia friendly” (C4). Another thought it was important for management to listen to what is happening on the ground by considering feedback from family members, residents, and staff as a process of establishing and maintaining the culture (C1).

Subtheme 2: Policies and procedures that enable dignity of risk

The village structures, policies, and processes need to allow practices that enable residents to engage in the village and to make choices in all aspects of their lives. The organization’s policies will be important to promote dignity of risk. One participant who manages a local group home described her approach to enabling dignity of risk by having the family sign a waiver:

“[W]e just decided that we would support exactly what she did the day before she moved in, which was go[ing] for long bike rides every day, multiple times. I got the family to sign a risk form to say that if she gets hit by traffic and gets lost, that’s the risk that they’re willing to take on behalf of [name] and she whizzes off every day. She can’t read stop signs. She drives into Woolworths on her trike even during COVID” (S1).

However, participants suggested this would be a delicate balancing act requiring strong relationships with family members who accept that the consequences are better than the alternative of “a lack of freedom of movement” (R9).

“[T]here is...the yin and the yang, to what degree are we going to be putting up the rights of people with dementia to do what they want to do daily, even though that might put them at risk? Versus what are...the moral and probably legal responsibilities of the organization to protect them from that risk” (R6).

“I think we probably agree with (R6) in the sense that, you know, people should be able to do what they want to do within their safety and...the idea is not to say ‘no, you can’t do it’, but it’s about yes and how we can do it to make it as safe as possible” (S4).

This balancing of dignity of risk versus safety was an important topic in the workshops. A participant living with dementia (P1) and a carer (C4), as well as a researcher with knowledge of Australia’s first village for people living with dementia in Tasmania (R6), felt there is a point where the risks of not having an external boundary could become too great and the care providers will have a duty to ensure they are safe.

Theme 4: Care staff who promote an enabling person-centered care environment

The funding and staffing models and the number of staff were considered important to achieving an open village without external boundaries. The funding model was considered critical to whether staff can sustain the model of care:

“[It is] absolutely about the resourcing of care. And yes, it’s about training people in person-centered [care] and is about having enough staff that they can...walk with that person they enable...[t]hat’s about deinstitutionalization, but it is also about resourcing” (R9).

Staffing resources should be sufficient to allow staff to be flexible and responsive, and available to support the level of dementia that the person is experiencing. For example: “You’d have a care plan around every person. They [go] one-on-one to the café. The person goes in a group in [this] setting” (S1). Staff who actively promote the organization’s mission, vision and values were deemed necessary and having “the right people involved, who are committed, really fostering that engagement and collaboration and the culture” (S3). Staff need to be “supported to enable and create a relaxed environment in the care contexts” with strategies to “make staff comfortable with the more open environment.” (R4).

Knowing the individual will also be a key strategy of person-centered care, enablement and developing meaningful activities and “is the foundation of everything” (S1). As presented in Theme 2, Subtheme 2 by R9, an appropriate staffing model and knowledge of person-centered care can also help the resident to engage in a broad range of activities meaningfully.

The new model of care was recognized to present some challenges for staff “on a day-to-day potentially, sometimes hour-by-hour basis” (R4). This will be a challenge for staff who have experience working in traditional residential aged care facilities. However, one participant suggested employing only “switched-on dynamic team members that understand the modelling concept from the very beginning and removing those that don’t very quickly” (S1). However, it was recognized that if “this [model of care] gets bigger, Australia-wide, I just wonder where all those people are going to come from” (P2).

Theme 5. Meaningful activities should meet the needs of all individuals living in the village

Meaningful engaging activities that offered individuals choices were important to the functioning of the village and a way of maintaining a person’s dignity.

“[O]ne of the key ways of maintaining dignity for everyone in this situation is to be able to retain as much of your previous life – your life when you were completely well – as possible. And that’s been the most difficult thing about residential care because everything goes, right down to the clothes you wear” (C2).

A participant said “the right environment and culture can give the person with dementia a sense of self-esteem and purpose again” (P1).

An important consideration was for meaningful activities at an appropriate level for all people to be able to engage, with inclusive and engaging communication, ensuring that the instructions are simplified and an environment conducive to inclusivity.

“[O]ne of the beauties of this kind of open community...is that all of your everyday activities are there and available. But, just having them available doesn’t mean they’re accessible to all people at their different stages of dementia...Something that the community would need is how you look at tailoring an activity throughout the community.” (R7).

One former carer elaborated on the need to tailor the activities as “People [with dementia] can so easily get lost, even with the carer. But, you know, they’ve only got to turn their back to the carer. Oh, where did they go?” (C2). Another former carer agreed, stating that if their partner with dementia “wanted to go off for a walk somewhere, I think I would rather somebody went with him.” (C3).

The need to enable people to continue doing the things they did before moving into the village, to maintain their sense of dignity, independence and self-worth was discussed (C2). The importance of residents being able to leave the community was also discussed, such as with trips to the National Gallery of Australia, walking groups, and attending daycare centers (S1, S4). However, “if a person is not able to go out anymore, then there should be something happening in the village or community center or whatever in the village to accommodate those people” (P3).

Paid employment within the village and volunteering within the community were discussed (P2, S4, R7) to address the needs of people living in the village, as these roles may promote better mental health.

“Offer positions in those cafes and stores to the residents...guess that would keep the cost down, but it would give them some purpose as well as something to do and keep their brains engaged” (P2).

“My idea was, people living with dementia still got a lot to offer the society and community around them. So, to take that knowledge that they want to be part of something better, but feel valued for what they [are] doing, was to give them some paid roles...So, for example...childcare or gardening” (S4).

Enabling people from the community, particularly across generations, to engage with residents on-site was seen as an important meaningful activity. One participant said “people [with dementia] are inherently lonely, and they’ve lost the village” (S1). While there is planned to be a childcare center on-site, intergenerational engagement was seen to be important to change “the culture forever about being with our elders who are living with dementia.” (S1). Participants also suggested that residents may be able to assist other community members with babysitting (S4, R7) or shopping (R7).

Several participants in the face-to-face group discussed the importance of the outdoors and gardens and having a community garden in the village to bring people together (S1, S2, C3, L1).

“Gardening, ensuring that [people living with dementia are involved] at every point along the spectrum from purchasing plants, choosing and purchasing plants in a...nursery type environment, to planting and nurturing plants. Harvesting, whether it’s flowers and fruit or vegetables, whatever and then potentially cooking and nutrition classes. It could be multigenerational involving the childcare center or nearby primary schools” (L1).

Theme 6. The built environment is designed to enable maximum engagement and safety

Subtheme 1: Built environment

Developing an enabling, relaxed environment that supports an inclusive culture, was recognized as important across each workshop. Use of spatial, environmental and wayfinding information in the village may help individuals easily navigate the space.

“[T]he environment needs to be easy to get around, visible from all parts of the village, signposted, attractive with places of interest resting spots, greenery and perhaps animals, that sort of thing. And the benefits would be that it would encourage people to move around the village, exercise, enjoy the outdoor environment and reap the benefits of being in the outdoors, and they could easily find their way to shop services and things like that.” (C3).

Spaces for interaction were considered essential:“[I]t has to be accessible and safe for all people, but it also has to be accessible and safe for people with dementia and without dementia” (S2), and should be designed appropriately:“[I]f children are also using the walking paths, you might have scooters or bicycles, scooting around the village at the same time if someone was trying to go for a bit of a stroll” (C3).

It was thought that the gardens and green spaces would be part of a central space, with buildings (including residential, businesses, and organizational facilities) located around the peripheries.

“In my mind, there’s going to be a central core to it, where the people actually live and it’s clear there’s going to be a lot of staff around. It’s going to be very familiar to the residents there. And that’s where they will spend, I suspect most of their time. And then there’s sort of more outer core where you’ve got the shared facilities, where people from a community come in, but again, there’s going to be staff and a lot of knowledgeable people in that sort of band” (R8).

Participants (S1, R6, R8) expressed some uncertainty due to not knowing specific information about the space where the village will be built and about what recommendations may need to be made to address specific contextual issues:

“[H]ighlighting how important the choice of the site is going to be. If you can, if you can find the right site where it is essentially a residential site. It’s not surrounded by motorways or roads with heavy lorries...It hasn’t got any railway lines or rivers to fall in. Then, you know, I think there is a much better chance of success” (R8).

The inclusion of people other than those living with dementia was also raised:

“[I]f there were other apartments available to rent that were not for people with dementia, and then it doesn’t become a dementia village, it becomes a dementia inclusive village and people with dementia happen to live in residential care” (R7).

The internal village space design was also considered important. Internal buildings need to be designed with an understanding of what the space is for, and how the space is used, including the music and lighting (S3). One participant suggested the internal environment should be inspired by the Dutch who “have this beautiful word, ‘gezellig’, which is sort of comfortable, relaxed, homely. And it makes you want to be there” (R2). This includes spaces where the community would be encouraged to visit and spend time: “We need to design for a relaxed environment. We’re making a space where we want people to come and stay and interact with each other.” (R1).

Subtheme 2: Safety

Safety was an underlying concern across workshops. Upskilling staff and the local community were seen necessary to manage safety. “It does take a village to look after people with dementia” (C1) and people in the community would “have to be attentive to be there, and that’s a big one” (S1).

A dementia-enabling community was seen to help keep the residents safe.

“That is the cushioning ground...to support those individuals to return or to continue exploring or to contact a staff member that can then continue to go for that walk with that person obviously wants to go on...it’s about risk management and risk minimization and harm minimization, not risk removal. And I think that that can be really hard to communicate. I think we’re a very risk-averse society.” (R9)

One participant was particularly concerned about safety, citing poor statistics for people living with dementia who get lost, but also said: “I think if you can plan some of those things with the protocols with the staffing, with the education, as well as the actual environment itself, that contributes to some of the safety concerns” (C4).

“I think there’s a huge amount of fear around the idea of people getting lost and wandering out of the place, but I think that – isn’t there also some evidence...that if you actually... unlock the doors...people don’t go, because there’s plenty to do within the village, it’s home. And why would you want to go?” (C3).

Subtheme 3: Technology

Technology should also be embedded into the village in the initial build and utilized to support staff to enable a relaxed environment. It may also have the added benefit of reassuring families about the care and safety of their family members. For example, tracking devices were seen by some to have benefits “A person could wear a watch or and [sic] if it had a location type device that would enable families to feel confident about their loved one leaving the facility” (C2), and “Technology that supports identifying falls, for example, means that the particular staff member didn’t have to feel anxious about it” (R4).

However, others expressed concerns about relying on technology to help achieve the open village concept “We’re not sure because we get into areas where it becomes human rights issues if we put monitors on them and things like that” (C4).

“I get concerned when we use more cameras for surveillance to try and maintain safety because, that’s still not [being] able to actually intervene, if there is a threat if somebody else is coming into that room or that building” (R9).

DISCUSSION

The concept of an open village designed for people living with dementia with cause to draw on a high level of care was supported by participants. The NGT method was used as a form of idea generation to assist in planning a proposed village in the ACT region. There was no opposition to the concept. However, some participants were apprehensive about how the safety of residents with dementia can be maintained. The priorities of ranked ideas across the three groups were similar, focused on the community surrounding the village, education, and the development of an empowering organizational culture focused on inclusivity, person-centered care, and enabling people living with dementia the dignity of risk. Further analysis of the ideas and transcripts of discussions from each workshop revealed nuances of potential barriers to achieving the vision of a safe and equitable village.

One of the primary conclusions was the importance of the support of the community surrounding the village. This support could be gathered by engaging the community before the first sod is turned over through communication about the development, values of the organization (e.g., inclusion, enablement, and dignity of risk), and the potential benefits to local community members. Education of the local community about dementia was also deemed important, and using already established programs could address this need. Education may not only contribute to the destigmatization of dementia but also create ‘zones of safety’. This is important because while awareness and acceptance of dementia are increasing, stigma remains, and people in the surrounding community may not want the village near their homes [12]. Education and communication may not only foster interest in the village but counteract the phenomenon of NIMBYism (‘Not In My Back Yard’), a pejorative term used to describe opposition to the construction or development of something in one’s local area because of the perception it would reduce the quality of life of residents or be otherwise undesirable. Several participants raised the likelihood of NIMBYism occurring and the need for strategies to offset objections. NIMBYism is not new in Australia and was experienced during the deinstitutionalization and setting up of community care and group home initiatives in the 1990 s for people with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities [20]. Therefore, anticipating local opposition has been described as just as important as the project concept, finding a site, and funding [21]. Other key strategies for engaging and educating the community may include using positive print, visual or social media where stories are used to put a face to the people who will live there. This may generate empathy with the audience by getting them to reflect on their thoughts and connections to their own home and lives [22, 23], aligning with a suggestion by two participants to use vignettes to tell the stories of people living with dementia.

Another key finding concerned strategies to engage with and educate potential on-site businesses and partners. Negative attitudes and lack of knowledge of dementia may affect the ability of the village to attract partners on-site and subsequently affect the viability of businesses and services. The staff of businesses choosing to operate in the village will require education and training. This will be even more pertinent if businesses engage people living with dementia in the workforce, as suggested by workshop participants. Another strategy that may foster engagement in the village is involving potential businesses and services in the design. Previous initiatives for housing for people experiencing homelessness have designed the physical environment to add value to the local area through beautification and strategic building in underinvested areas [24]. The vision for the village to include a cafe, grocery store, hairdresser, childcare, community gardens, and attractive landscaping may serve this purpose. Further considerations for engaging with the local community include appealing to higher-order beliefs and values by emphasizing facts, anticipating and countering misinformation, and working with proponents for high-quality dementia care [22].

Following the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, there has been a greater acceptance of the need to address the issues associated with the built environment for people needing care, the models of care, and the organizational cultures within those environments [2]. Equipping staff and families of people living with dementia with knowledge about the benefits of appropriately built environments, person-centered care, and the fostering of interpersonal relationships were also highly valued by participants. The best way to build strong interpersonal relationships and meet individual needs and preferences is by having specific knowledge about each person [25, 26]. This can have many positive effects, including greater engagement in meaningful activities according to the preferences of the person living with dementia [25–27]. Staff can also enable each individual to engage in the built environment as appropriate to their cognitive and physical abilities [10, 26, 28]. However, changing established organizational cultures within typically risk-averse organizations can be difficult. Despite the acceptance of the principles of dignity of risk, there remains limited success in overcoming the preference for aged care providers to avoid financial and legal risk, leaving an imbalance between theory and practice [29]. Workshop participants discussed mechanisms to mitigate risk, including waivers. However, aged care providers cannot avoid all risks, including reputational risks [29]. This has led to a defensive approach where the default is to be cautious and avoid potential harm while prioritizing compliance and reporting standards.

Certain participants in this study repeatedly returned to the issue of balancing safety and individual choice. However, across workshops, there was not a clear distinction between the role or experience of participants and the concerns expressed. Several participants raised the risks of people living with dementia being free to move outside of the village into the local community and the requirement for adequate supervision by the staff. As such, other participants responded by highlighting the need for dignity of risk to be woven into all aspects of operations, management, staffing and community education for residents to be safe. In each workshop, the relatively small number of participants with concerns about safety were persuaded to a degree by other participants, that the vision could be achieved. Generally, issues raised about the community being able to access the village and overall safety, were outweighed by opinions emphasizing the role of education, staffing, and culture to minimize the risks. Participants also had concerns about known barriers to enabling dignity of risk including lack of staff training and knowledge; inadequate staff ratios; poor communication between staff and family; a risk-averse physical environment; legal concerns; non-individualized care; and lack of accountability on respecting the rights of people living with dementia [29, 30]. Therefore, an open village without external boundaries would require community management and responsiveness to dignity of risk principles [31].

Small-scale residential care models are associated with fewer physical demands, lower workload, and job autonomy among staff [32]. Staff autonomy and satisfaction, in turn, affect retention and recruitment [33]. Some participants viewed the number of staff as secondary to the quality of staff, their knowledge and beliefs about dementia, and person-centered care. However, person-centered care requires flexibility and consistency in implementation, which relies on motivated staff, sufficient time, and sufficient staff numbers [27]. Currently, aged care staff in Australia are already experiencing high stress and cognitive burden due to multitasking and a range of workforce factors that prevent them from delivering truly person-centered care [34]. Small-scale residential dementia care is proposed as a way to potentially offset some of these challenges. However, known limitations of this in Australia include lack of availability and putative cost, even though in some instances, running costs may in fact be lower [35], and staff retention may be improved [8]. Additionally, small-scale care models such as the Green House and Green Care Farm models provide higher quality care than traditional aged care models [9, 36]. In addition, infection control may be better in these homes, as evidenced in the current COVID-19 pandemic [37]. There is a need for more research into psychosocial models of providing best practice dementia care which underpins the ability to provide small-scale homes that have a community focus.

To our knowledge, there is no research on village designs for people living with dementia where there are no external boundaries, nor are we aware of documented examples of clustered dementia care where residents have free access to the outdoors within a non-gated community. The present study included views from a range of stakeholders pertaining to how a vision for an open village without external boundaries could potentially be achieved. To maximize the quality of life of people living with dementia, and to reduce stigma within local communities, innovative models of dementia care, supported by research, are urgently needed.

Limitations

It is important to note several limitations of this study. The expertise within each group was different and may have influenced the results in each group, and the size of each group was different. While this was a purposive sample, not all invited participants agreed to participate, meaning the full scope of perspectives may not have been considered. For example, an architect declined to participate. However, this was offset by one participant being a global expert on the built environment for people living with dementia. In addition, while most of the researchers who participated were also clinicians, there may have been an over-representation of expertise from academia. There was also an underrepresentation of people familiar with aged care policy and regulatory requirements. While not being representative of all of the stakeholders who would be involved in the development of a new village, the study was novel and included a wide range of stakeholders, including people with dementia and carers, to work towards problem solving to improve the quality of dementia care [38]. Interestingly, the top ideas from each workshop were similar despite the variety of experiences and expertise of participants across each group. A strength of our study was including people with knowledge of Australia’s first village for people living with dementia in Tasmania. Our findings overlap with Tierney et al. (2022), who researched Korongee village for people living with dementia in Hobart, Tasmania [7]. Tierney et al. (2022) also recognized the need for education in the community, a safe and enabling physical environment, and meaningful activities, as expressed by 12 community members in online focus groups. However, due to COVID-19, none of the participants in this study had visited the village.

Conclusion

Stakeholders and experts supported the concept of a future village for people living with dementia with minimal or no external boundaries, balancing opportunity and risk. Critical to its success will be educating the surrounding community and having an organizational culture that can balance staffing requirements and residents’ safety by maximizing the dignity of risk and opportunity for meaningful activities for people living with dementia. A cohesive and well-planned strategy incorporating all stakeholders of the new village will be required for the type of village being proposed to prove successful in advancing the quality of residential care for people living with dementia in Australia and worldwide. Given the challenging environment, significant work and investment will be required to achieve the vision. However, this study demonstrates that it is a worthy pursuit with potential to transform residential care for people living with dementia and truly integrate it within a neighborhood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for their time, expertise and enthusiasm for this project.

FUNDING

We also sincerely thank the Snow Foundation for supporting this research project and The Neighbourhood Canberra.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nathan M D’Cunha, Jane Thompson, Susan Kurrle, and Nicole Smith are volunteer members of the Board of The Neighbourhood, Canberra. There are no other conflicts of interest to report.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Raw qualitative data is not available due to ethical requirements.

REFERENCES

[1] | Harrison SL , Dyer SM , Laver KE , Milte RK , Fleming R , Crotty M ((2022) ) Physical environmental designs in residential care to improve quality of life of older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: , CD012892. |

[2] | Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety ((2021) ) Final Report: Care, Dignity and Respect – Volume 1. https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report, Last updated March 1, 2021, Accessed on October 6, 2022. |

[3] | Brennan S , Doan T ((2022) ) Small-scale living environments’ impact on positive behaviors and quality of life for residents with dementia. J Aging Environ 37: , 181–201. |

[4] | de Boer B , Beerens HC , Katterbach MA , Viduka M , Willemse BM , Verbeek H ((2018) ) The physical environment of nursing homes for people with dementia: Traditional nursing homes, small-scale living facilities, and green care farms. Healthcare (Basel) 6: , 137. |

[5] | Gibson D , D’Cunha NM , Bail K , Isbel S ((2022) ) Small scale dementia care in Australia: An implementation study of innovation in funding, technology and resident-led care. British Society of Gerontology 51st Annual Conference: Better Futures for Older People-Towards Resilient and Inclusive Communities’. |

[6] | D’CunhaNM, IsbelS, BailK, GibsonD ((2023) ). ‘It’s like home’ – A small-scale dementia care home and the use of technology: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15728. |

[7] | Tierney L , Doherty K , Breen J , Courtney-Pratt H ((2022) ) Community expectations of a village for people living with dementia. Health Soc Care Community 30: , e5875–e5884. |

[8] | Jilek R ((2022) ) The Community Home Model – small scale community embedded residential aged care for people living with younger onset dementia. Glob J Aging Geriatr Res 2: , doi: 10.33552/GJAGR.2023.02.000527. |

[9] | de Boer B , Hamers JPH , Zwakhalen SMG , Tan FES , Verbeek H ((2017) ) Quality of care and quality of life of people with dementia living at green care farms: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 17: , 155. |

[10] | Zeisel J , Bennett K , Fleming R ((2020) ) World Alzheimer Report 2020: Design, dignity, dementia: Dementia-related design and the built environment. https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2020/ Last updated September 21, 2020, Accessed on October 29, 2022. |

[11] | Ibrahim JE , Davis MC ((2013) ) Impediments to applying the ‘dignity of risk’ principle in residential aged care services. Australas J Ageing 32: , 188–193. |

[12] | Steele L , Swaffer K , Phillipson L , Fleming R ((2019) ) Questioning segregation of people living with dementia in Australia: An international human rights approach to care homes. Laws 8: , 18. |

[13] | Harvey N , Holmes CA ((2012) ) Nominal group technique: An effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int J Nurs Pract 18: , 188–194. |

[14] | McMillan SS , Kelly F , Sav A , Kendall E , King MA , Whitty JA , Wheeler AJ ((2014) ) Using the Nominal Group Technique: How to analyse across multiple groups. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 14: , 92–108. |

[15] | MasonS, LingJ, MosoiuD, ArantzamendiM, TserkezoglouAJ, PredoiuO, PayneS ((2021) ) Undertaking research using online nominal group technique: Lessons from an international study (RESPACC). J Palliat Med 24: , 1867–1871. |

[16] | McMillan SS , King M , Tully MP ((2016) ) How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm 38: , 655–662. |

[17] | Newham R , Weir N , Ferguson A , Bennie M ((2022) ) Identifying the important outcomes to measure for pharmacy-led, clinical services within primary care: A nominal group technique approach. Res Social Adm Pharm 19: , 468–476. |

[18] | Braun V , Clarke V ((2021) ) One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 18: , 328–352. |

[19] | Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J ((2007) ) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Quality Health Care 19: , 349–357. |

[20] | Wiesel I , Whitzman C , Gleeson B , Bigby C ((2019) ) The National Disability Insurance scheme in an urban context: Opportunities and challenges for Australian cities. Urban Policy Res 37: , 1–12. |

[21] | Iglesias T ((2002) ) Managing local opposition to affordable housing: A new approach to NIMBY. J Affordable Housing Commun Dev Law 12: , 78–122. |

[22] | Rockne A ((2018) ) Not in my backyard: Using communications to shift “NIMBY” attitudes about affordable housing. University of Minnesota. |

[23] | Mingoya C ((2015) ) Building together: Tiny house villages for the homeless: A comparative case study. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. |

[24] | Evans K ((2021) ) It takes a tiny house village: A comparative case study of barriers and strategies for the integration of tiny house villages for homeless persons in Missouri. J Plan Educ Res, doi: 10.1177/0739456X211041392. |

[25] | Ericsson I , Kjellström S , Hellström I ((2013) ) Creating relationships with persons with moderate to severe dementia. Dementia (London) 12: , 63–79. |

[26] | Kim SK , Park M ((2017) ) Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging 12: , 381–397. |

[27] | Lee JY , Yang E , Lee KH ((2022) ) Experiences of implementing person-centered care for individuals living with dementia among nursing staff within collaborative practices: A meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud 138: , 104426. |

[28] | de Witt L , Fortune D ((2019) ) Relationship-centered dementia care: Insights from a community-based culture change coalition. Dementia (London) 18: , 1146–1165. |

[29] | Courtney A , Iredale F , Heaven J , Tang E ((2022) ) Dignity of risk in aged care. Aust Health Law Bull 30: , 111–114. |

[30] | Woolford MH , de Lacy-Vawdon C , Bugeja L , Weller C , Ibrahim JE ((2020) ) Applying dignity of risk principles to improve quality of life for vulnerable persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 35: , 122–130. |

[31] | Marsh P , Kelly L ((2018) ) Dignity of risk in the community: A review of and reflections on the literature. Health Risk Soc 20: , 297–311. |

[32] | Zwakhalen SM , Hamers JP , van Rossum E , Ambergen T , Kempen GI , Verbeek H ((2018) ) Working in small-scale, homelike dementia care: Effects on staff burnout symptoms and job characteristics. A quasi-experimental, longitudinal study. J Res Nurs 23: , 109–122. |

[33] | Hodgkin S , Warburton J , Savy P , Moore M ((2017) ) Workforce crisis in residential aged care: Insights from rural, older workers. Aust J Public Adm 76: , 93–105. |

[34] | Gibson D , Willis E , Merrick E , Redley B , Bail K ((2022) ) High demand, high commitment work: What residential aged care staff actually do minute by minute: A participatory action study. Nurs Inq. e12545. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12545 |

[35] | Dyer S , van den Berg M , Barnett K , Brown A , Johnstone G , Laver K , Lowthian J , Maeder AJ , Meyer C , Moores C , Ogrin R , Parrella A , Ross T , Shulver W , Winsall M , Crotty M ((2020) ) Review of innovative models of aged care, Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Flinders University. https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/research-paper-3-review-innovative-models-aged-care. Last updated January 24, 2020, Accessed on November 14, 2022. |

[36] | Afendulis CC , Caudry DJ , O’Malley AJ , Kemper P , Grabowski DC , THRIVE Research Collaborative ((2016) ) Green house adoption and nursing home quality. Health Serv Res 51: , 454–474. |

[37] | Zimmerman S , Dumond-Stryker C , Tandan M , Preisser JS , Wretman CJ , Howell A , Ryan S ((2021) ) Nontraditional small house nursing homes have fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22: , 489–493. |

[38] | Reeve E , Chenoweth L , Sawan M , Nguyen TA , Kalisch Ellett L , Gilmartin-Thomas J , Tan E , Sluggett JK , Quirke LS , Tran K , Ailabouni N , Cowan K , Sinclair R , de la Perrelle L , Deimel J , To J , Daly S , Whitehead C , Hilmer SN ((2023) ) Consumer and healthcare professional led priority setting for quality use of medicines in people with dementia: Gathering unanswered research questions. J Alzheimers Dis 91: , 933–960. |

[39] | Bunn F , Burn AM , Goodman C , Robinson L , Rait G , Norton S , Bennett H , Poole M , Schoeman J , Brayne C ((2016) ) Health services and delivery research. In Comorbidity and dementia: A mixed-method study on improving health care for people with dementia (CoDem), Southampton (UK). |