COVID-19 Case Fatality and Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

Previous studies have identified dementia as a risk factor for death from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, it is unclear whether Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an independent risk factor for COVID-19 case fatality rate. In a retrospective cohort study, we identified 387,841 COVID-19 patients through TriNetX. After adjusting for demographics and comorbidities, we found that AD patients had higher odds of dying from COVID-19 compared to patients without AD (Odds Ratio: 1.20, 95%confidence interval: 1.09–1.32, p < 0.001). Interestingly, we did not observe increased mortality from COVID-19 among patients with vascular dementia. These data are relevant to the evolving COVID-19 pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

Dementia has consistently been identified as a risk factor for death from the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1–8]. However, mixed results have been reported regarding whether Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an independent risk factor for COVID-19 mortality, likely due to the relatively small sample size studied [9, 10]. The goal of our study was to determine whether AD patients had a higher COVID-19 case fatality rate (CFR) compared to a large demographically matched cohort of COVID-19 patients without AD. Critically, we included 30 comorbidities from the Elixhauser comorbidity index in our analysis, controlling for known non-AD contributions to the COVID-19 CFR [11, 12].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We compared COVID-19 CFR in patients with and without AD from the TriNetX research network, as we did previously with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [13]. TriNetX is a health research database with deidentified medical records of over 50 million patients, mostly from the United States. We extracted data on April 14, 2021, but only used data through February 17, 2021, in order to allow time for mortality outcomes to be resolved. Thus, these data likely are prior to major variant spread and vaccination [14].

Patients were identified if they had one or more International Classification of Diseases (ICD; Ninth revision: ICD-9-CM, Tenth revision: ICD-10-CM) codes in their medical records for COVID-19: U07.1 (2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease (WHO)); B97.29 (Other coronavirus as the cause of diseases classified elsewhere); B34.2 (Coronavirus infection, unspecified); or J12.81 (Pneumonia due to SARS-associated coronavirus) between January 20, 2020 and February 17, 2021. Patients with ICD-9 code 079.89 (Other specified viral infection) were excluded to reduce the likelihood of including patients without COVID-19. The study included all patients with COVID-19 recorded in their medical records from participating healthcare organizations in both inpatient and outpatient care settings. We used the Elixhauser comorbidity index to account for comorbidities; this index accounts for major factors contributing to hospital mortality [15]. History of comorbidities listed in the Elixhauser comorbidity index were identified if the patient had a corresponding ICD code for the condition in their medical records captured in TriNetX. Deaths documented at the participating healthcare organizations were recorded. Patients were identified as having AD if at least one of the following ICD codes were listed in their medical records: 331.0, G30, G30.0, G30.1, G30.8, or G30.9. For vascular dementia, the following ICD codes were used: 290.40, 290.41, 290.42, 290.43, F01, F01.5, F01.50, F01.51. For dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), the following ICD codes were used: 331.82 and G31.83. For frontotemporal dementia (FTD), the following ICD codes were used: 331.1, 331.11, G31.0, G31.01, G31.09. Descriptive statistics included proportions for categorical variables and medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. For demographic and counts of comorbidities information, see Supplementary Table 1. Of note, our hypotheses pertained to AD and COVID-19, and Supplementary Table 1 is included for completeness.

We used three approaches to account for differences between patients with AD and patients without AD. First, we performed multivariable logistic regressions to explore associations between AD, vascular dementia, DLB, FTD, age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities (all comorbidities included in the Elixhauser comorbidity index, except other neurological disorders), and mortality. Any deaths during the study period captured in the medical records of the participating health-care organizations were included in the analysis. All variables were inserted into the multivariable logistic regression model, and the odds ratio was estimated for each fixed effect. In this context, the odds ratio estimates the ratio of dying of COVID-19 with and without AD.

Second, we matched each AD COVID-19 case to 5 control COVID-19 cases with the same age, sex, race and Elixhauser comorbidity index, and performed a conditional logistic regression analysis to account for potential residual confounding. As a third convergent analysis, we performed propensity score matching and matched each AD COVID-19 case to 5 control COVID-19 cases with the same propensity score that were calculated from age, sex, race, ethnicity, and comorbidities from the Elixhauser comorbidity index, and then performed conditional logistic regression.

Data were requested from TriNetX and all analyses were conducted with R. TriNetX access is provided at no cost to University of Iowa researchers through the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, part of the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award program [16]. The results were considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05. No imputations were made for missing data. Adult patients 18 years and older were included in the dataset; of note, AD tends to affect older patients, and the median age of our patient population was 50. We obtained a dataset of 388,029 patients with COVID-19 initially but removed 188 patients with unknown gender. We did not impose any further exclusion criteria to limit selection bias. Our research is approved by the IRB of University of Iowa, under IRB protocol: 202005138.

RESULTS

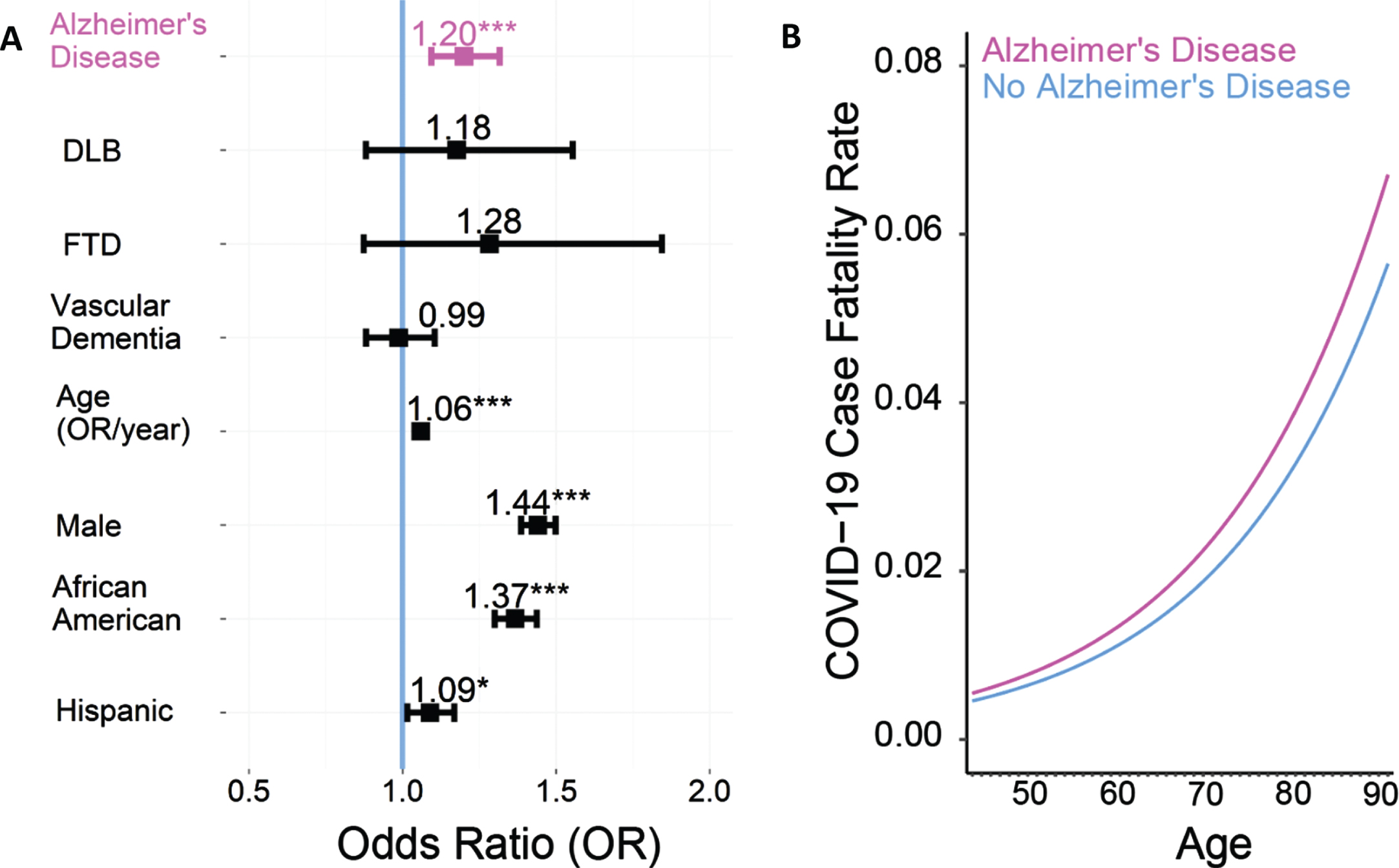

We identified 387,841 patients with COVID-19, of whom, 4,174 had AD, 2,765 had vascular dementia, 375 had DLB, and 235 had FTD. Prior research has shown higher CFRs in males versus females [1, 17], African Americans versus Caucasians [1, 18], and elderly versus younger patients [1, 17]. We performed logistic regression with age, sex, race, ethnicity, and 30 comorbidities included in the Elixhauser Comorbidity index as covariables. This analysis revealed that the odds of mortality from COVID-19 were significantly elevated in the AD group (Odds Ratio (OR): 1.20, 95%confidence interval (CI): 1.09–1.32, p < 0.001; Fig. 1A, B). In addition, the OR of COVID-19 mortality from patients with AD versus patients without AD was similar for men (Odds Ratio (OR): 1.21, 95%confidence interval (CI): 1.05–1.39) as well as women (OR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.05–1.35). For the full results of logistic regression, see Table 1.

Fig. 1

COVID-19 patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have an increased case fatality rate (CFR). A) Odds ratio (OR) of COVID-19-induced case-fatality rate; an OR of greater than 1 means a greater risk of dying of COVID-19. COVID-19 patients with AD (n = 4174) have an increased CFR compared to those without AD (n = 383,667, odds ratio: 1.20, 95%confidence interval: 1.09–1.32, p < 0.001; this would mean that all other factors being equal, a patient with AD would have a ∼20%increased chance of COVID-19 mortality). Logistic regression was performed with age, sex, race, ethnicity and 30 comorbidities from the Elixhauser comorbidity index included as covariables. Data from 387,841 COVID-19 patients in the TriNetX research network. B) COVID-19 CFR was higher across age groups > 50 years. Lines represent the model fit of each year (with age as a fixed effect) for AD patients (pink) and those without AD (blue).

Table 1

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with mortality in adults with COVID-19 coded in the TriNetX research network as of February 17, 2021 (n = 387,841)

| Multivariable logistic regression results | ||

| Characteristics | Death with | P |

| COVID-19, OR (95%CI) | ||

| Age (per year) | 1.059 (1.057–1.060) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.44 (1.39–1.50) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Black or African American | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.23 (1.16–1.29) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 0.017 |

| Unknown | 1.21 (1.15–1.26) | <0.001 |

| Dementia disorders | ||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | <0.001 |

| Vascular dementia | 0.99 (0.88–1.10) | 0.83 |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 1.18 (0.88–1.55) | 0.26 |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 1.28 (0.87–1.84) | 0.19 |

| Comorbidities within the Elixhauser comorbidity index | ||

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 2.98 (2.85–3.13) | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 2.25 (2.14–2.36) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1.88 (1.80–1.96) | <0.001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 1.72 (1.56–1.89) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 1.52 (1.44–1.60) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 1.39 (1.31–1.1.47) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 1.39 (1.32–1.46) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.37 (1.30–1.45) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 1.28 (1.21–1.35) | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 1.20 (1.10–1.31) | <0.001 |

| Psychoses | 1.11 (1.00–1.24) | 0.053 |

| Lymphoma | 1.08 (0.96–1.21) | 0.22 |

| Obesity | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0.003 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 0.82 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.19 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 0.92 (0.88–0.97) | 0.001 |

| Drug abuse | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.087 |

| Blood loss anemia | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.10 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.89 (0.85–0.94) | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, excluding bleeding | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.03 |

| Valvular disease | 0.88 (0.83–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease | 0.86 (0.80–0.93) | <0.001 |

| Solid tumor, without metastasis | 0.81 (0.76–0.86) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 0.81 (0.77–0.86) | <0.001 |

| AIDS/HIV | 0.81 (0.63–1.03) | 0.10 |

| Depression | 0.80 (0.77–0.84) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 0.78 (0.73–0.83) | <0.001 |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 0.75 (0.71–0.79) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 0.70 (0.67–0.74) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio.

To further assess for residual confounding by age, sex, race, and comorbidities, we exactly matched each AD COVID-19 case to 5 control COVID-19 cases with the same age within 1 year, sex, race, and Elixhauser comorbidity index. We then performed a conditional logistic regression and again found an elevated odds of death in patients with AD compared to age, sex, race, and Elixhauser comorbidity index matched controls (OR = 1.38, 95%CI:1.29–1.47, p < 0.001). We replicated this analysis with 1,000 random matchings with the effect being statistically significant in all replicates. Finally, we performed propensity score matching of each AD COVID-19 patient to 5 control COVID-19 patients with propensity scores calculated from age, sex, race, ethnicity, and comorbidities from the Elixhauser index. This was followed by conditional logistic regression, and, for a third time, we found an increased OR of dying from COVID-19 among AD patients (OR = 1.14, 95%CI:1.04–1.24, p = 0.004).

Interestingly, for vascular dementia, we used a similar approach with logistic regression with age, sex, race, ethnicity, and 30 comorbidities included in the Elixhauser Comorbidity index as covariables and found that the odds of dying from COVID-19 was not consistently increased among patients with vascular dementia compared to patients without vascular dementia (OR: 0.99, 95%CI: 0.88–1.10, p = 0.83). Similarly, the ORs of COVID-19 mortality were not reliably increased among patients with DLB (OR:1.18, 95%CI: 0.88–1.55, p = 0.26) or FTD (OR: 1.28, 95%CI:0.87–1.84, p = 0.19) (Fig. 1A).

DISCUSSION

In summary, we performed a retrospective analysis of the TriNetX database and found that COVID-19-related CFR was increased in AD patients, independent of age, sex, race, ethnicity, and comorbidities from the Elixhauser comorbidity index. Vascular dementia, on the other hand, did not increase the COVID-19 CFR after accounting for the demographics and comorbidities. We also did not see a significant increase in COVID-19 CFR among patients with DLB or FTD, although these two diseases can be challenging to diagnose, only a few hundred patients of these were included in our sample, and are difficult to compare to other studies because of our sample size and timing during the pandemic [9]. However, our results are convergent in finding that AD is an independent risk factor for COVID-19 mortality [9].

There are several possibilities for the association between AD, COVID-19, and mortality in the present study. Indeed, SARS-CoV2 can invade the central nervous system [19], and COVID-19 patients frequently have neurological impairments [20], which may be compounded in neurodegenerative conditions like PD and AD.

These results have several limitations. First, the TriNetX research network includes de-identified data from over 40 healthcare organizations primarily in the US. While this allowed us to analyze patient data from across the country, we were unable to account for confounding regional data that could increase mortality, such as low access to high-level health care (i.e., intensive care units, ventilators, etc.) and varying treatment strategies by region. Second, this dataset does not have information on severity of AD, cognitive function, functional status, if patients are bedridden, or patients’ goals of care wishes, including DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) status, and there may be residual imbalances despite matching or a latent covariate that contributes to our observed effects. Third, this study only reports an association between COVID-19-related mortality and a diagnosis of AD; however, in this context, designs that are better suited to causal inference are challenging. Fourth, we do not have information on medications taken before or during the infection. Some medications may reduce the COVID-19 related mortality (e.g., monoclonal antibodies, dexamethasone) while others—or the conditions they treat—may be associated with increased risk of death (e.g., ACE inhibitors, DPP4 inhibitors) [21, 22]. Furthermore, the TriNetX database lacks explicit information on recovery. Fifth, it is possible that patients with AD are treated differently by the healthcare system or are more likely to have advanced directives. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved with vaccination, viral mutation, and treatments which may be highly relevant to mortality [23].

Our results provide evidence that caution may be required when providing care for patients with AD to prevent COVID-19, and consideration of this patient population when determining the ethics of vaccination priority, including in younger patients diagnosed with AD [24]. Despite progress on vaccination in the developed world, much of the global at-risk population remains unvaccinated. Furthermore, coronaviruses will likely remain a major threat in the coming years [25]. These data may have relevance for AD and other respiratory illnesses, which may involve similar risk factors and mechanisms [26]. Our work could also help guide health-care decisions on global COVID-19 policy as well as for caring for AD patients through future pandemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Q.Z. is supported by NIH/NINDS R25 NS079173, the NIH/NINDS NeuroNext Fellowship, and the physician scientist training program at University of Iowa. N.N. is supported by NIH R01 NS100849-A1. G.M.A. is supported by NIH K08 NS109287 and the Iowa Neuroscience Institute. J.L.S. is supported by NIH K23-NS117736.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/21-5161r2).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-215161.

REFERENCES

[1] | Williamson EJ , Walker AJ , Bhaskaran K , Bacon S , Bates C , Morton CE , Curtis HJ , Mehrkar A , Evans D , Inglesby P , Cockburn J , McDonald HI , MacKenna B , Tomlinson L , Douglas IJ , Rentsch CT , Mathur R , Wong AYS , Grieve R , Harrison D , Forbes H , Schultze A , Croker R , Parry J , Hester F , Harper S , Perera R , Evans SJW , Smeeth L , Goldacre B ((2020) ) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584: , 430–436. |

[2] | Docherty AB , Harrison EM , Green CA , Hardwick HE , Pius R , Norman L , Holden KA , Read JM , Dondelinger F , Carson G , Merson L , Lee J , Plotkin D , Sigfrid L , Halpin S , Jackson C , Gamble C , Horby PW , Nguyen-Van-Tam JS , Ho A , Russell CD , Dunning J , Openshaw PJ , Baillie JK , Semple MG , investigators IC ((2020) ) Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 369: , m1985. |

[3] | Zuin M , Guasti P , Roncon L , Cervellati C , Zuliani G ((2020) ) Dementia and the risk of death in elderly patients with COVID-19 infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 36: , 697–703. |

[4] | Harrison SL , Fazio-Eynullayeva E , Lane DA , Underhill P , Lip GYH ((2020) ) Comorbidities associated with mortality in 31,461 adults with COVID-19 in the United States: A federated electronic medical record analysis. PLoS Med 17: , e1003321. |

[5] | Wang Q , Davis PB , Gurney ME , Xu R ((2021) ) COVID-19 and dementia: Analyses of risk, disparity, and outcomes from electronic health records in the US. Alzheimers Dement 17: , 1297–1306. |

[6] | Tahira AC , Verjovski-Almeida S , Ferreira ST (2021) Dementia is an age-independent risk factor for severity and death in COVID-19 inpatients. Alzheimers Dement, doi: 10.1002/alz.12352. |

[7] | Vrillon A , Mhanna E , Aveneau C , Lebozec M , Grosset L , Nankam D , Albuquerque F , Razou Feroldi R , Maakaroun B , Pissareva I , Cherni Gherissi D , Azuar J , Francois V , Hourregue C , Dumurgier J , Volpe-Gillot L , Paquet C ((2021) ) COVID-19 in adults with dementia: clinical features and risk factors of mortality-a clinical cohort study on 125 patients. Alzheimers Res Ther 13: , 77. |

[8] | Numbers K , Brodaty H ((2021) ) The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 17: , 69–70. |

[9] | Matias-Guiu JA , Pytel V , Matias-Guiu J ((2020) ) Death rate due to COVID-19 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 78: , 537–541. |

[10] | Li J , Long X , Huang H , Tang J , Zhu C , Hu S , Wu J , Li J , Lin Z , Xiong N ((2020) ) Resilience of Alzheimer’s disease to COVID-19. J Alzheimers Dis 77: , 67–73. |

[11] | Sharabiani MT , Aylin P , Bottle A ((2012) ) Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care 50: , 1109–1118. |

[12] | Moore BJ , White S , Washington R , Coenen N , Elixhauser A ((2017) ) Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care 55: , 698–705. |

[13] | Zhang Q , Schultz JL , Aldridge GM , Simmering JE , Narayanan NS ((2020) ) Coronavirus Disease 2019 case fatality and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 35: , 1914–1915. |

[14] | Aleem A , Akbar Samad AB , Slenker AK ((2021) ) Emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 and novel therapeutics against Coronavirus (COVID-19). In StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL). |

[15] | Menendez ME , Neuhaus V , van Dijk CN , Ring D ((2014) ) The Elixhauser comorbidity method outperforms the Charlson index in predicting inpatient death after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472: , 2878–2886. |

[16] | TriNetX University of Iowa ICTS, https://icts.uiowa.edu/investigators/biomedical-informatics-core/trinetx |

[17] | Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention ((2020) ) [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 41: , 145–151. |

[18] | Ferdinand KC , Nasser SA ((2020) ) African-American COVID-19 mortality: a sentinel event. J Am Coll Cardiol 75: , 2746–2748. |

[19] | Solomon IH , Normandin E , Bhattacharyya S , Mukerji SS , Keller K , Ali AS , Adams G , Hornick JL , Padera RF Jr. , Sabeti P ((2020) ) Neuropathological features of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 383: , 989–992. |

[20] | Chen X , Laurent S , Onur OA , Kleineberg NN , Fink GR , Schweitzer F , Warnke C ((2021) ) A systematic review of neurological symptoms and complications of COVID-19. J Neurol 268: , 392–402. |

[21] | Rossi GP , Sanga V , Barton M ((2020) ) Potential harmful effects of discontinuing ACE-inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19 patients. Elife 9: , e57278. |

[22] | Iacobellis G ((2020) ) COVID-19 and diabetes: Can DPP4 inhibition play a role? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 162: , 108125. |

[23] | Abu-Raddad LJ , Chemaitelly H , Butt AA , National Study Group for C-V ((2021) ) Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants. N Engl J Med 385: , 187–189. |

[24] | Clift AK , Coupland CAC , Keogh RH , Hemingway H , Hippisley-Cox J ((2020) ) COVID-19 mortality risk in Down syndrome: results from a cohort study of 8 million adults. Ann Intern Med 174: , 572–576. |

[25] | Perlman S ((2020) ) Another decade, another coronavirus. N Engl J Med 382: , 760–762. |

[26] | Ganguli M , Dodge HH , Shen C , Pandav RS , DeKosky ST ((2005) ) Alzheimer disease and mortality: a 15-year epidemiological study. Arch Neurol 62: , 779–784. |