Effect of Learning to Use a Mobility Aid on Gait and Cognitive Demands in People with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease: Part II – 4-Wheeled Walker

Abstract

Background:

Cognitive deficits and gait problems are common and progressive in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Prescription of a 4-wheeled walker is a common intervention to improve stability and independence, yet can be associated with an increased falls risk.

Objectives:

1) To examine changes in spatial-temporal gait parameters while using a 4-wheeled walker under different walking conditions, and 2) to determine the cognitive and gait task costs of walking with the aid in adults with AD and healthy older adults.

Methods:

Twenty participants with AD (age 79.1±7.1 years) and 22 controls (age 68.5±10.7 years) walked using a 4-wheeled walker in a straight (6 m) and Figure of 8 path under three task conditions: single-task (no aid), dual-task (walking with aid), and multi-task (walking with aid while counting backwards by ones).

Results:

Gait velocity was statistically slower in adults with AD than the controls across all conditions (all p values <0.025). Stride time variability was significantly different between groups for straight path single task (p = 0.045), straight path multi-task (p = 0.031), and Figure of 8 multi-task (0.036). Gait and cognitive task costs increased while multi-tasking, with performance decrement greater for people with AD. None of the people with AD self-prioritized gait over the cognitive task while walking in a straight path, yet 75% were able to shift prioritization to gait in the complex walking path.

Conclusion:

Learning to use a 4-wheeled walker is cognitively demanding and any additional tasks increases the demands, further adversely affecting gait. The increased cognitive demands result in a decrease in gait velocity that is greatest in adults with AD. Future research needs to investigate the effects of mobility aid training on gait performance.

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive deficits, balance problems, and gait disorders are common and progressive in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 2], leading to impaired mobility, falls, and fall-related injuries [3]. Importantly, people with dementia have an annual fall risk of 60–80%, twice that of the cognitively normal [4], and have a higher risk of major fall-related injuries, such as hip fractures [5]. Current fall prevention guidelines have not been successful in reducing falls in people with dementia [6]. A first-line rehabilitation intervention strategy for balance and gait problems is provision of a mobility aid (e.g., cane or walker); yet, paradoxically, use of a mobility aid in people with dementia has been shown to be associated with a three-fold increased odds of falling independent of other factors [7].

Mobility requires significant cognitive resources for balance and adapting walking to negotiate obstacles, and planning a path [8]. Executive function is essential for mobility [9]; deficits in executive function happen early in AD and lead to an increased fall risk [10]. Observing people during a gait task while they simultaneously perform another task—the dual-task paradigm—is an accepted way to assess the relationship between cognition and mobility, and reflects circumstances that lead to falls in real-life [11, 12]. If the demands of doing multiple tasks simultaneously exceed the cognitive capacity of an individual, then the performance on one or both tasks will deteriorate [11]. The cognitive load, or difference between the single and combined tasks, quantifies the demands on executive function resources.

The increased falls risk with mobility aid use could be the result of increased cognitive demands related to attentional processing and neuromotor control that leads to an unstable gait [13]. Cognitive demands will vary with task novelty and task complexity, an increased cognitive demand is associated with an increased falls risk [14, 15]. Task complexity can include the configuration of the walking path executed. People with AD experience a significant deterioration in gait quality compared to age and sex matched controls when walking in a Figure of 8 pattern than walking in a straight line [16]. In this study, lower executive function scores were associated with a longer time to walk in a Figure of 8 pattern while maneuvering around obstacles [16]. Ambulation with a mobility aid is also a complex motor activity and results in increased cognitive demands in healthy younger adults when using a standard walker and wheeled walker [17, 18]. Cognitive demands while walking with a 4-wheeled walker were greater in adults with AD compared with cognitively healthy older adults, particularly when maneuvering around obstacles [19]. This study by Hunter et al. did not assess spatial or temporal gait parameters, but quantified cognitive load as the difference in time (which is directly related to velocity) and the number of steps (which is a temporal marker) to complete a gait task with and without use of a 4-wheeled walker.

While research has demonstrated an increased cognitive load in people with AD while learning to use a 4-wheeled walker [19], it is unknown whether changes in temporal and spatial gait characteristics that are markers of instability occur as well. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to evaluate in cognitively-healthy adults and people with mild to moderate AD: 1) the changes in gait parameters of velocity and stride time variability, and 2) the gait and cognitive task cost of newly learning to use a 4-wheeled walker using a dual-task paradigm. It was hypothesized that using a 4-wheeled walker would result in gait instability that was more pronounced with complex walking paths and in conjunction with the performance of cognitive tasks while walking in the AD group than the cognitively healthy older adults.

METHODS

Participants

Adults without cognitive impairment and adults with a diagnosis of AD were included in the study. The AD group was recruited from a local day program and had a geriatrician confirmed diagnosis of AD based on the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-AD and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ARDRA) criteria [20]. Controls were recruited from a local fitness program. Approval of the protocol by the Heath Sciences Ethics Review Board of the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada was obtained prior to the study commencement. Informed consent was provided by either the participant or their substitute decision maker. For participants with AD, if the substitute decision maker provided informed consent then the participant provided assent to participate in the study.

For people with AD, the inclusion criteria were 1) confirmed diagnosed of AD within the mild to moderate stage as indicated by a Mini-Mental State Examination [21] score of 11–24 [22], 2) be at least 50 years of age, and 3) be able to walk for 30 meters without assistance from another person and do not depend on a mobility device for independence. Adult controls met inclusion criteria by 1) being at least 50 years of age, 2) being able to walk independently without the need of support from another person or a mobility device, 3) no subjective cognitive complaints, and 4) a score on the MMSE greater than 24. Exclusion criteria for both groups were: 1) inability to understand verbal instructions given in English, 2) having a concurrent neurological disorder that affected motor control, or 3) having a walking impairment due to musculoskeletal disorders. All data were collected over 15 months from March 2017 to May 2018.

Outcome measures

Participant information for socio-demographics (e.g., age, sex, years of education), detailed medical information (e.g., number of comorbidities, number of prescription medications), and physical activity levels (assessed by self-report: vigorous, engages in structured exercise program for 30 min three times a week; moderate, engages in physical activity at least three times a week; sedentary physical activity less than three times a week) were obtained from either the participant or their substitution decision maker. The Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Basic Activities of Daily Living scales were used to record independence status during activities of daily living [23]. The Iconographical-Falls Efficacy Scale, a validated tool for older adults with and without cognitive impairment was used to assess fear of falling [24, 25]. Vision was assessed for contrast sensitivity using the Mars Contrast Sensitivity Test (Perceptrix®) and spatial relations with the Stereo Fly Test (Stereo Optical Company®). All participants completed the same study procedures.

Single-task cognitive assessment

A seated baseline measure for the time to complete the cognitive task of performing 10 serial subtractions by ones from 100 was completed by all participants prior to the gait assessment. Time to the nearest 100th of a second with a stop watch, total responses and number of correct responses were recorded.

Gait assessment

Two tri-axial accelerometers (Locomotion Evaluation and Gait System, LEGSys™, BioSensics, Cambridge, MA) were attached to the frontal plane of each of the participant’s lower limbs to obtain spatial-temporal gait characteristics. The gait parameters of interest were velocity and stride time variability [26]. Stride time variability was quantified using the coefficient of variation:

There were a total of 6 test conditions - two walking path configurations: a straight path (SP) of 6 meters and the Figure of Eight Walking Test (F8) [27] each with three task conditions. The task conditions were: single-task (ST) conditions in which participants walked each path configuration without use of the 4-wheeled walker (SP_ST, F8_ST), dual-task (DT) conditions in each path was completed using a 4-wheeled walker (SP_DT, F8_DT), and multi-task (MT) condition of walking each path configuration while using a 4-wheeled walker and counting backwards from 100 by 1s (SP_MT, F8_MT). Cognitive performance during the multi-task testing was measured with the recording of the number of responses and the accuracy of the responses. Participants were not instructed to prioritize the gait or the cognitive task during the multi-task testing. The order of testing was straight path single-task, straight path walking with 4-wheeled walker, straight path multi-task counting backwards by 1 s while using 4-wheeled walker, Figure of 8 single-task, Figure of 8 walking with 4-wheeled walker, and Figure of 8 multi-task counting backwards by 1 s while using 4-wheeled walker.

Participants were provided with a 4-wheeled walker that was sized to each person by the research assistant (i.e., height of the handles for the walker were adjusted to be level with wrist crease with the arm hanging by the participant’s side when standing erect). Each person was given instructions on how to appropriately use the 4-wheeled walker while walking, repeating instructions as required for people in both groups. Participants were allotted 5 min to practice walking around the room with the gait aid before gait testing commenced. In order to get accustomed to the study protocol, participants performed a practice trial for each walking task at a self-selected usual walking speed. Testing consisted of two trials at a self-selected usual walking speed per condition that were averaged for analysis.

Data analysis

Gait velocity and stride time variability data were tested for meeting assumptions of normality Shapiro-Wilks test, kurtosis and skewness index, and Levine’s Test of constant variance. Stride time variability deviated from normality and statistical analysis was performed using log10 transformation of the data. The comparison of velocity and stride time variability across walking conditions and between groups was completed using a 2-way repeated measures ANOVA, adjusted for age. The test condition (i.e., the 6 walking tasks) comprised the within-group variable and group (i.e., controls and AD) was the between-groups variable. Where appropriate for control of multiple comparison bias, per-comparison was undertaken using a Bonferroni correction. Cohen’s d effect size (ES) was calculated to quantify the magnitude of the difference between the two groups. Benchmark values for ES to estimate the magnitude of the effect were classified as: trivial (<0.20), small (0.20 to <0.50), moderate (0.50 to <0.80), or large (>0.80) [28].

To address the second objective, two new outcome measures were derived from the data (gait cost and cognitive cost associated with the multitasking). A negative multiplier was used in the calculation of both gait and cognitive cost so that negative values indicate a decay in performance and positive values indicate an improvement in performance. Gait cost for velocity was calculated as the percentage change in velocity for the single-task of usual walking to each of the DT and MT conditions for straight path and figure of 8:

Task cost for cognitive performance was determined by first calculating the correct response rate (CRR) for the single-task cognitive test and multi-task tests as: (Response rate per second X percent correct). CRR accounts for speed and accuracy of responses given [29]. Cognitive task cost was calculated as:

The interpretation of the task cost value is the same for both gait and cognition. A negative value indicates poorer performance under the dual-task or multi-task conditions (e.g., slower velocity under the dual-task condition). A positive value indicates better performance under dual-task or multi-task conditions (e.g., faster velocity or greater number of responses or greater accuracy of responses). A comparison of gait task cost for velocity between the groups was again done, using a split-plot repeated measures ANOVA with group and walking condition as factors.

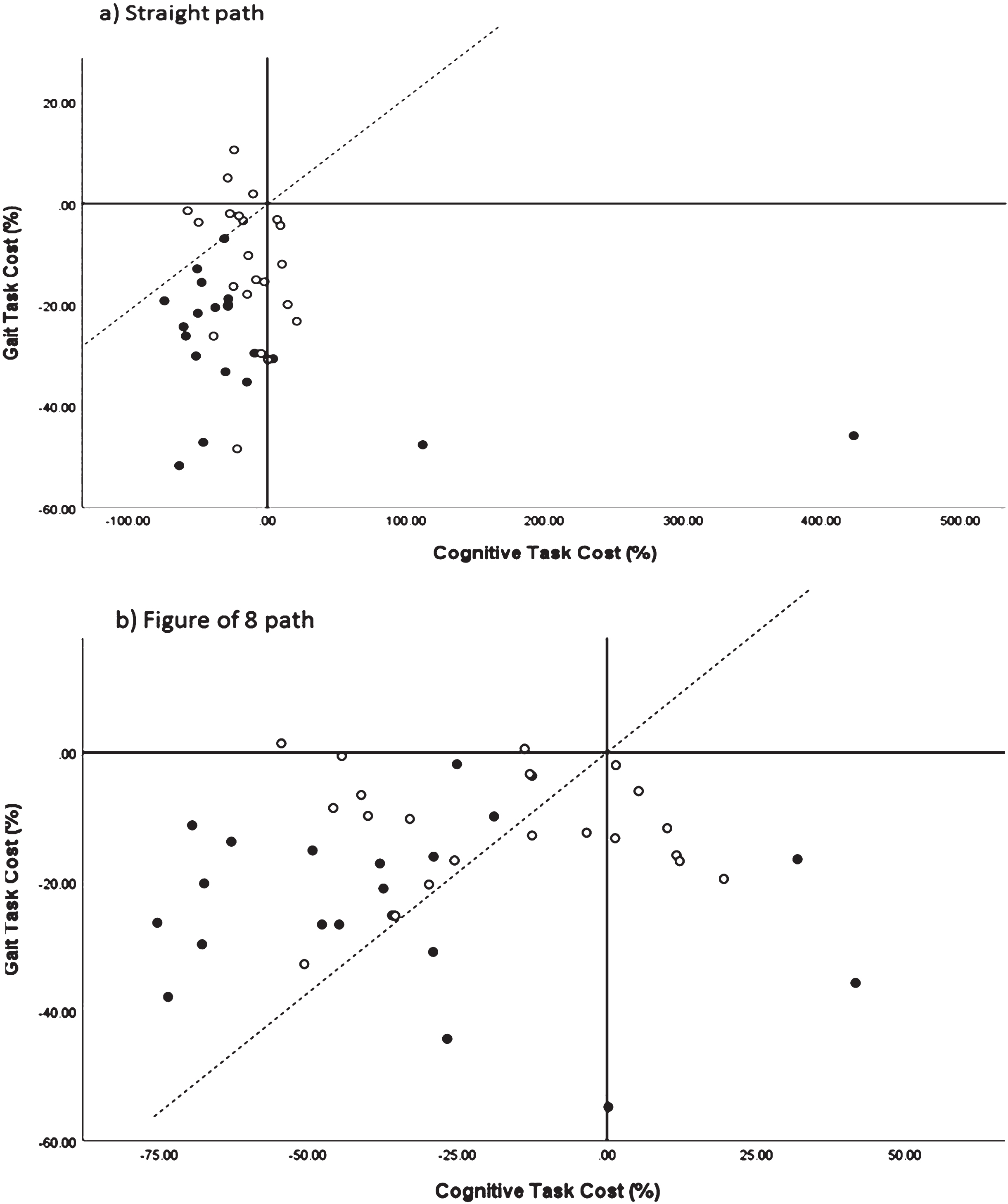

A performance-resource operating characteristic (POC) graph was created by plotting cognitive task cost (x-axis) versus gait task cost (y-axis) for the multi-task conditions to demonstrate the trade-off between the gait and cognitive tasks when performed simultaneously [15]. Performance could fall into one of four quadrants: 1) upper left – improvement of gait with worsening of cognitive task, 2) upper right – improvement of gait with improvement of cognitive task, 3) lower left – worsening of gait with worsening of cognitive task, and 4) lower right – worsening of gait with improvement of cognitive task. Performance that falls on the axes at 0% task cost for gait and cognition indicates no change in performance between single- and dual-task conditions. A diagonal line cuts through quadrants 2 and 3, this line indicates a 1 : 1 trade-off during dual-task performance; to the left of this line gait is prioritized and the cognitive task is prioritized to the right of the line [15].

A priori, sample size calculation was based on our previous research in people with dementia [19], and suggested that a sample size of 25 participants per group is needed for a power of 80% with α= 0.05 to detect a 10% difference in dual-task cost.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven participants with AD were recruited, but four were unable to subtract by 1 s and there were technical issues with the accelerometers for another three participants. Twenty-four controls were recruited, but two had incomplete data for the gait testing. Therefore, twenty participants with AD (age = 79.1±7.1 years) and 22 adult controls (age = 68.5±10.7 years) were included in the analysis for this study. Participants with AD were older, had less formal education, were less able to complete instrumental activities of daily living and scored lower on cognitive measures than the older adult controls (see Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample of cognitively-healthy adult controls and adults with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

| Characteristic | Mean±SD or frequency and percentage (Min–Max) | ||

| Adult Controls (n = 22) | AD (n = 20) | p | |

| Age (y) | 68.5±10.7 | 79.1±7.1 | 0.001 |

| (54.0–90.0) | (61.0–88.0) | ||

| Sex (n, % female) | 17 (74) | 10 (50) | 0.147 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/cm2) | 29.4±5.8 | 26.1±3.6 | 0.027 |

| (20.1–40.7) | (18.4–33.2) | ||

| Education (y) | 16.0±3.9 | 12.4±2.8 | 0.004 |

| (12.0–26.0) | (8.0–17.0) | ||

| Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale | 12.4±2.5 | 13.2±4.5 | 0.445 |

| (10.0–18.0) | (10.0–25.0) | ||

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | 8.0±.0 | 2.4±1.5 | <0.001 |

| (8.0 –8.0) | (.0–8.0) | ||

| Basic Activities of Daily Living | 6.0±.0 | 5.4±2.4 | |

| (6.0–6.0) | (.0–6.0) | ||

| History of falls in past 12 months (n, %) | 5 (22) | 3 (15) | 0.586 |

| High Contrast Sensitivity (logCS units) | 0.14±0.12 | 0.33±0.23 | 0.002 |

| (–0.01–0.40) | (.00–1.10) | ||

| Low Contrast Sensitivity (logCS units) | 0.35±0.20 | 0.50±0.25 | 0.031 |

| (0.10–0.70) | (0.10–1.00) | ||

| Stereo Fly Test (circles, seconds of arc) | 71.36±81.61 | 254.67±254.95 | 0.016 |

| (40.00–400.00) | (60.00–800.00) | ||

| Stereo Fly Test (animals, seconds of arc) | 100.00±0.00 | 176.92±130.09 | 0.054 |

| (100.00–100.00) | (100.00–400.00) | ||

| Physical Activity Level (n, %) | <0.001 | ||

| Sedentary | 0 (0) | 5 (25) | |

| Moderate | 4 (17) | 11 (55) | |

| Vigorous | 19 (83) | 4 (20) | |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | 29.6±0.73 | 21.2±4.2 | <0.001 |

| (27.0–30.0) | (13.0–28.0) | ||

p-value for statistical significance adjusted for multiple comparisons, p < 0.005.

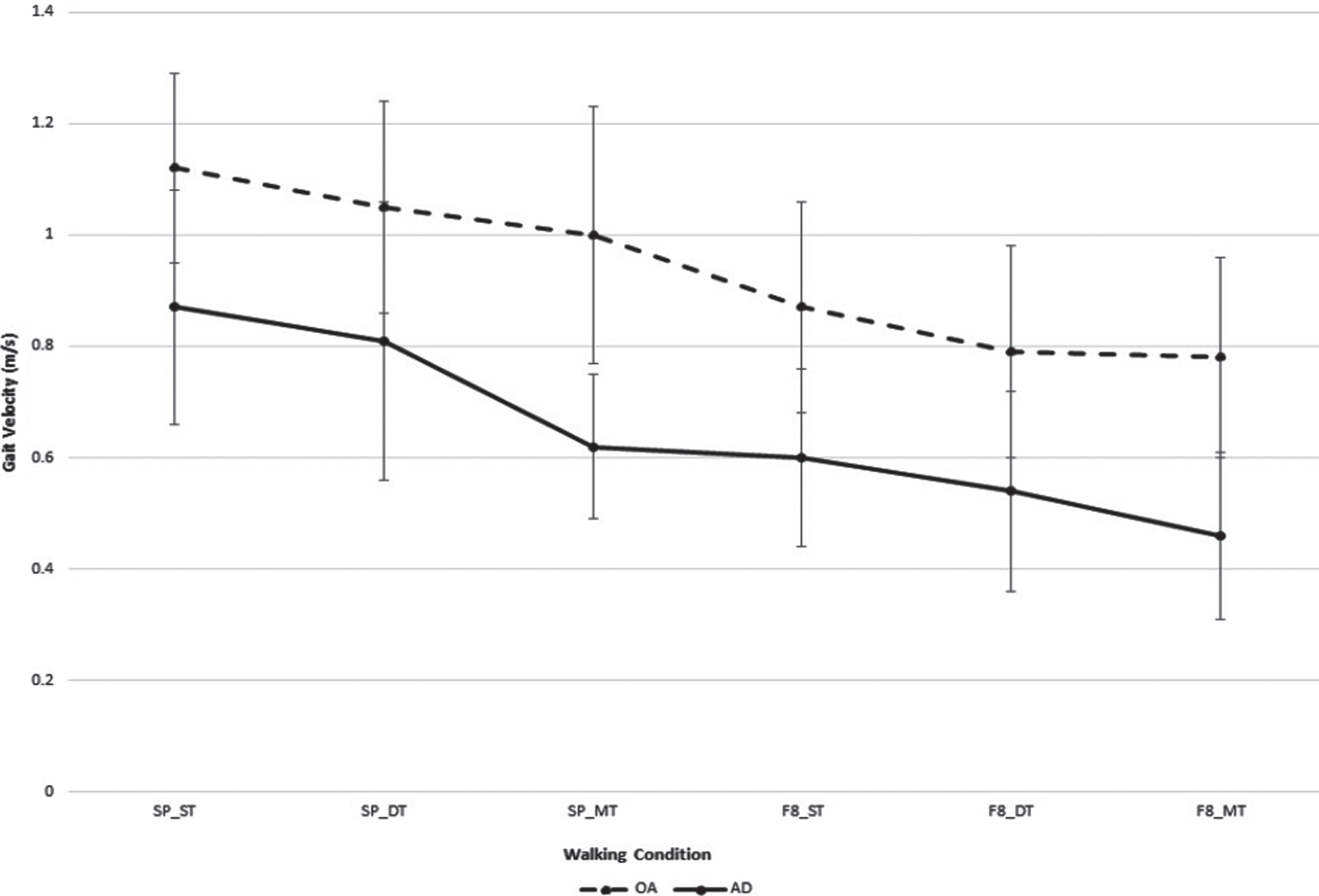

Gait velocity results suggested a non-significant interaction between group and test (p = 0.552), but statistically significant main effects for group (p = 0.001). This is graphically depicted in (Fig. 1) (data presented in Supplementary Table 1). Gait velocity was statistically significantly different between the groups for each of the test conditions (p values < 0.025).

Fig.1

Gait velocity (mean±standard deviation) for older adults and adults with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease while learning to use a 4-wheeled walker under straight and Figure of 8 path configuration. *analysis adjusted for age; SP_ST, straight path and walking without the walker; SP_DT, straight path and walking with 4-wheeled walker; SP_MT, straight path and walking with a 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones; F8_ST, figure of 8 path and walking without the walker; F8_DT, figure of 8 path and walking with a 4-wheeled walker; F8_MT, figure of 8 path and walking with 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones.

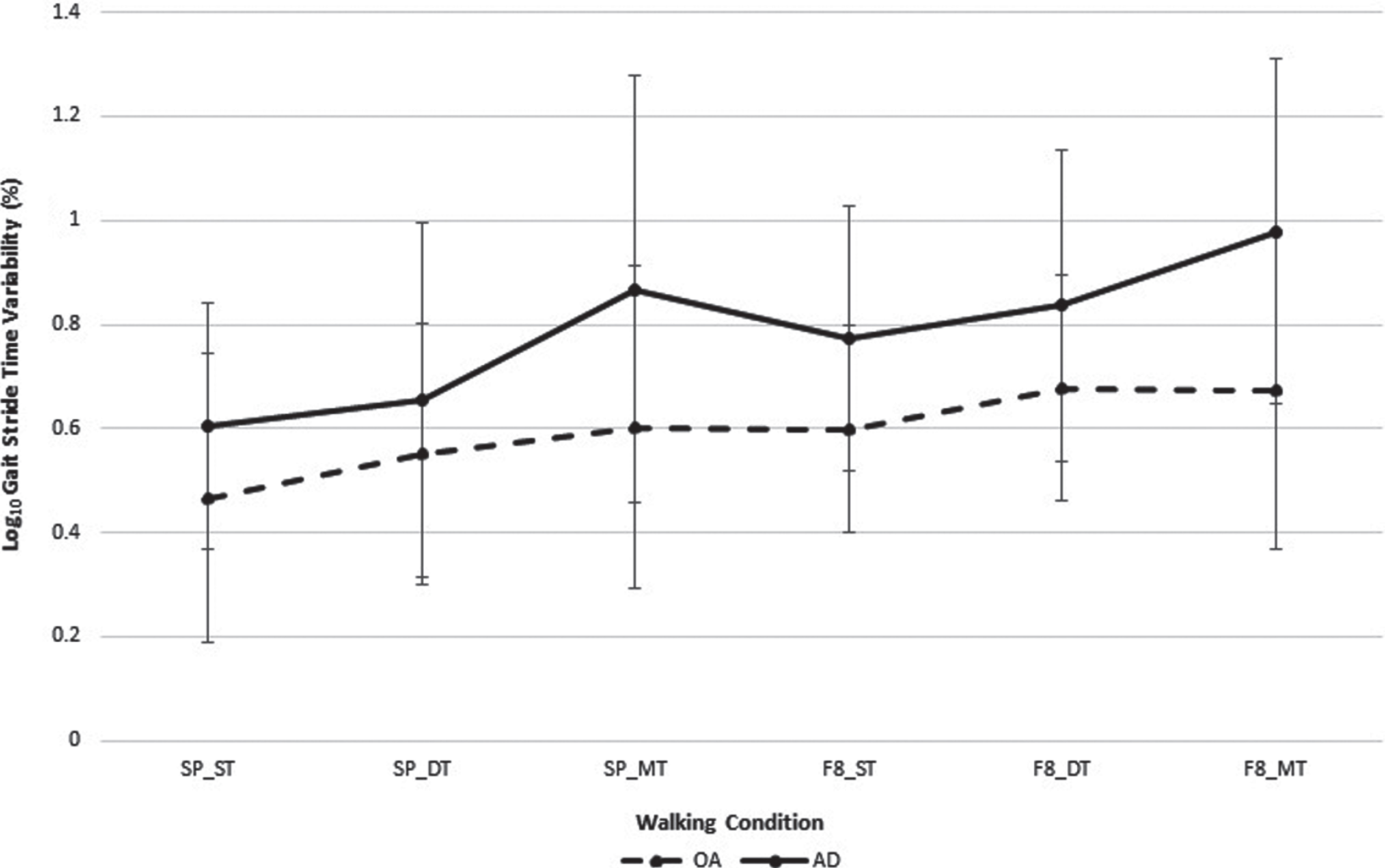

Stride time variability demonstrated no statistically significant interaction (p = 0.685) or main effects for test condition (p = 0.378). This is graphically depicted in (Fig. 2) (data presented in Supplementary Table 2). There were statistically significant differences between groups for the straight path single task (p = 0.045, Cohen’s d = 0.54), straight path multi-task (p = 0.031, Cohen’s d = 0.73), and Figure of 8 multitask (p = 0.036, Cohen’s d = 0.96) conditions, the effect sizes ranged from moderate to large.

Fig.2

Stride time variability (mean±standard deviation) for older adults and adults with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease while learning to use a 4-wheeled walker under straight and Figure of 8 path configuration. *analysis adjusted for age; SP_ST, straight path and walking without the walker; SP_DT, straight path and walking with 4-wheeled walker; SP_MT, straight path and walking with a 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones; F8_ST, figure of 8 path and walking without the walker; F8_DT, figure of 8 path and walking with a 4-wheeled walker; F8_MT, figure of 8 path and walking with a 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones.

Task costs for gait velocity and cognition are presented in Table 2. The interaction for condition x group was not statistically significant (p = 0.135), but only gait velocity task cost demonstrated a significant effect for group (p = 0.022). Pairwise comparisons demonstrated a statistically significant difference between groups for simple path multitasking (p = 0.010, Cohen’s d = 1.19) and Figure of 8 multitasking (p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 1.21) There were no statistically significant interaction or main effects for cognitive task cost. The POC graph (Fig. 3) demonstrates that in the straight path and Figure of 8 path, performance on cognition and gait deteriorated in the multi-task test condition for both groups. In the straight path multi-task condition, 0% of people with AD self-prioritized gait over cognitive performance compared to 36.4% in the adult controls. In the Figure of 8 multi-tasking condition, 75% (15/20) people with AD and 59% (13/22) adult controls self-prioritized gait over cognitive performance.

Table 2

Task costs for gait and cognition for cognitively-healthy adults and adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) while walking with a 4-wheeled walker and walking with a 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones

| Mean±SD | 2-way repeated measures ANOVA* (p) | ||||

| SP_DT | SP_MT | F8_DT | F8_MT | ||

| A. Task cost for gait (%) | |||||

| AD | –8.03 (12.76) | –27.82 (12.47) | –10.15 (12.09) | –24.04 (12.59) | Condition: p = 0.316 |

| Adults | –6.88 (10.36) | –12.15 (13.86) | –9.21 (6.82) | –11.19 (8.68) | Group: p = 0.022 |

| Condition x Group: p = 0.135 | |||||

| p = 0.972 | p = 0.010 | p = 0.491 | p = 0.003 | Post hoc pairwise-comparisons | |

| d = 0.10 | d = 1.19 | d = 0.10 | d = 1.21 | (p and Cohen’s d effect size) | |

| B. Task cost for cognition (%) | |||||

| AD | –31.25 (39.94) | –36.75 (33.02) | Condition: p = 0.237 | ||

| Adults | –13.57 (20.26) | –17.92 (23.11) | Group: p = 0.162 | ||

| Condition x Group: p = 0.595 | |||||

SP_DT, straight path and walking with 4-wheeled walker; SP_MT, straight path and walking with 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones; F8_DT, figure of 8 path and walking with 4-wheeled walker; F8_MT, figure of 8 path and walking with 4-wheeled walker while counting backwards by ones; *analysis adjusted for age.

Fig.3

Performance-resource operating characteristic graph for demonstration of between task trade-offs of gait and cognitive tasks during multi-task gait testing (walking while using a 4-wheeled walker and counting backwards by ones) in cognitively healthy older adults (o) and people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (o).

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that people learning to use a 4-wheeled walker will have an increase in cognitive demands compared to usual unassisted walking. Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated differences between groups were only detected for the multitasking condition and the demands were greater for people with AD. Gait velocity was slower in people with AD for all the test conditions. Interestingly, people with AD had greater stride time variability compared to the adult controls for walking in a straight path alone and in the straight path and Figure of 8 with the walker while multitasking. Learning to walk with the 4-wheeled walker resulted in mutual interference for the gait and cognitive tasks in the multi-task test condition. Importantly, all of the people with AD prioritized the cognitive task when walking in a straight path and then shifted to the majority prioritizing gait in the complex walking path. This is the first study the authors are aware of to present the effects of learning to walk with a 4-wheeled walker on gait parameters and cognitive demands.

Wright et al. [17] were the first to evaluate the cognitive demands of people learning to use a walker. In their sample of healthy young adults, verbal response time to an auditory stimulus slowed while walking with a standard and 4-wheeled walker. Hunter et al. [19] found people with mild to moderate AD learning to use a 4-wheeled walker demonstrated increased cognitive demands when walking in a complex path maneuvering around obstacles, but not in a straight path compared to age and sex-matched controls. Consistent with the study by Hunter et al. [19], our study found cognitive demands were not increased in straight path walking with use of the 4-wheeled walker only; it was when the more complex activity of multi-tasking was performed that cognitive demands increased when walking in a straight path. Our results are consistent with the existing literature that learning to use a 4-wheeled walker is cognitively demanding for both cognitively-healthy adults and adults with AD, those demands are greatest for those with AD while multi-tasking.

It is understood that the concurrent performance of multiple tasks competes for attentional resources, but there is also an unconscious prioritization of the tasks in the absence of explicit instructions [12]. It is believed that older adults give priority to the gait task over the cognitive task to ensure stability and prevent falls while walking, what is called a posture-first strategy [11]. In our study, we found the gait and cognitive task costs during multi-task testing showed a deterioration in performance when using the 4-wheeled walker and counting backwards by ones. In the absence of explicit instructions for task prioritization in the combined test conditions, none of the adults with AD prioritized gait in the straight path which is consistent to findings in other patient populations where the cognitive task is found to be prioritized over gait, increasing the risk of falling [12]. In contrast, the majority of the older adults and adults with AD prioritized the gait task over the cognitive task in the complex path, adopting a posture-first strategy. Our finding that people with AD were able to shift task prioritization to gait in the more difficult test path configuration to achieve a posture-first strategy is a novel finding.

An increase in stride time variability has been demonstrated in people with AD in dual-task gait testing with a secondary cognitive task [30]. Stride time variability quantifies the automaticity of gait from one stride to the next during steady-state walking, with greater variability indicating an unstable gait pattern and an association with mobility decline and falls [31]. Our study found no relationship of increasing variability with increasing task complexity across the testing conditions for stride time variability. One explanation for the lack of an expected increasing stride time variability in the multi-tasking condition is that the serial subtraction by ones may have entrained and enhanced performance due to the rhythmicity of the counting. Beauchet et al. [32] found that some cognitively-healthy older adults were able to significantly improve their gait variability when performing a dual-task gait test through the rhythmicity of the gait and cognitive activity leading to an improvement in cognitive capacity for the combined activities. Yet, counting backwards has been found to increase stride time variability in older adults with dementia and frontal lobe dysfunction walking without aids [33]. Another explanation for our results is that the 4-wheeled walker could have provided increased stability from bilateral upper limb support thus offsetting the effects of the cognitive task. We did find some difference between groups for the people with AD having greater variability than the controls. The potential mechanism by which mobility aid use increases falls risk in people with dementia could be mediated by an increase in instability quantified as stride time variability caused by an increased cognitive load. The dementia process is associated with greater gait impairments than expected by the aging process alone, so the increased fall risk in people using a mobility aid is likely a proxy for advanced disease pathology associated with greater gait impairments [34].

The results from this study provide an interesting contrast to those seen in participants learning to use a single-point cane (See Part I [35]). Although the use of mobility aids led to impaired walking parameters in both study samples, changes in spatial-temporal gait parameter were more pronounced in the groups learning to use a single-point cane. However, it does highlight that even though single-point canes are considered an introductory mobility aid, our findings suggest they are most disruptive on walking abilities due to their unique motor sequencing demands. In the present study, the gait stride time variability appeared to increase with increasing task complexity, particularly in the AD group. Clinically, this finding may suggest that the response to increasing task complexity is also more varied in people with AD.

This study has several limitations to review and consider in the interpretation of the findings. Our sample is not generalizable as our participants were all recruited from a specialty day hospital program for people with dementia and therefore are not representative of all people with AD. We also did not recruit people with severe disease who were ambulatory, but 15% of enrolled people were unable to complete the counting task highlighting the variability even within the mild to moderate disease severity. There were also differences between the samples on age and reported levels of physical activity, though adjustment was done statistically future studies may benefit from age and sex matching of the sample. There are several strengths of this study including the assessment of gait parameters in order to detail the relationship between cognitive demands and gait performance. Though our secondary cognitive task used in the multi-tasking was serials subtraction by ones, a low complexity activity, it challenged the people with AD close to their performance limits which is important in evaluating the magnitude of effects in the cognitive-motor relationship. We also assessed task costs related to both gait and cognition, allowing the evaluation of task prioritization in the absence of explicit instructions.

Conclusion

Learning to use a 4-wheeled walker is cognitively demanding in both cognitively-healthy adults and people with mild to moderate AD. The adverse changes in gait were greatest in the people with AD. Importantly, any additional demands to the walking task and maneuvering around obstacles further adversely affects gait. The increased cognitive demands results in a decrease in gait velocity that is greatest in adults with AD, yet there was not a statistically significant increase in stride time variability across the tasks. Future research needs to investigate the effects of mobility aid training on gait performance and falls reduction in people with AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Karen Johnson, Director of Alzheimer Outreach Services of McCormick Home; Steve Crawford, CEO, McCormick Care Group and the staff and clients at the Alzheimer Outreach Services day program for their hospitality, assistance in organizing this project and participation in the data collection process. This study was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association (AARG-16-440671) and had no involvement in the conduct of the study.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-1170r3).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-181170.

REFERENCES

[1] | Wittwer JE , Webster KE , Menz HB ((2010) ) A longitudinal study of measures of walking in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Gait Posture 32: , 113–117. |

[2] | Suttanon P , Hill KD , Said CM , Dodd KJ ((2013) ) A longitudinal study of change in falls risk and balance and mobility in healthy older people and people with Alzheimer disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 92: , 676–685. |

[3] | Taylor ME , Delbaere K , Lord SR , Mikolaizak AS , Close JCT ((2013) ) Physical impairments in cognitively impaired older people: Implications for risk of falls. Int Psychogeriatr 25: , 148–56. |

[4] | Tinetti ME , Speechley M , Ginter SF ((1988) ) Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 319: , 1701–1707. |

[5] | Asada T , Kariya T , Kinoshita T , Asaka A , Morikawa S , Yoshioka M , Kakuma T ((1996) ) Predictors of fall-related injuries among community-dwelling elderly people with dementia. Age Ageing 25: , 22–28. |

[6] | Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society ((2011) ) Summary of the updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 59: , 148–157. |

[7] | Pellfolk T , Gustafsson T , Gustafson Y , Karlsson S ((2009) ) Risk factors for falls among residents with dementia living in group dwellings. Int. Psychogeriatrics 21: , 187. |

[8] | Lowry KA , Brach JS , Nebes RD , Studenski SA , VanSwearingen JM ((2012) ) Contributions of cognitive function to straight- and curved-path walking in older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93: , 802–807. |

[9] | Frank JS , Patla AE ((2003) ) Balance and mobility challenges in older adults: Implications for preserving community mobility. Am J Prev Med 25: , 157–163. |

[10] | Muir S , Gopaul K , Montero Odasso MM ((2012) ) The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 41: , 299–308. |

[11] | Woollacott M , Shumway-Cook A ((2002) ) Attention and the control of posture and gait: A review of an emerging area of research. Gait Posture 16: , 1–14. |

[12] | Yogev-Seligmann G , Hausdorff JM , Giladi N ((2008) ) The role of executive function and attention in gait. Mov Disord 23: , 329–342. |

[13] | Bateni H , Maki BE ((2005) ) Assistive devices for balance and mobility: Benefits, demands, and adverse consequences. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86: , 134–145. |

[14] | Muir-Hunter SW , Wittwer JE ((2015) ) Dual-task testing to predict falls in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Physiotherapy 102: , 29–40. |

[15] | McIsaac TL , Lamberg EM , Muratori LM ((2015) ) Building a framework for a dual task taxonomy. Biomed Res Int 2015: , 591475. |

[16] | Hunter SW , Divine A ((2018) ) The effect of walking path configuration on gait in adults with Alzheimer’s dementia. Gait Posture 64: , 226–229. |

[17] | Wright DL , Kemp TL ((1992) ) The dual-task methodology and assessing the attentional demands of ambulation with walking devices. Phys Ther 72: , 306–312; discussion 313-315. |

[18] | Wellmon R , Pezzillo K , Eichhorn G , Lockhart W , Morris J ((2006) ) Changes in dual-task voice reaction time among elders who use assistive devices. J Geriatr Phys Ther 29: , 74–80. |

[19] | Muir-Hunter S , Montero-Odasso M , Montero Odasso M ((2017) ) The attentional demands of ambulating with an assistive device in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Gait Posture 54: , 202–208. |

[20] | Albert MS , DeKosky ST , Dickson D , Dubois B , Feldman HH , Fox NC , Gamst A , Holtzman DM , Jagust WJ , Petersen RC , Snyder PJ , Carrillo MC , Thies B , Phelps CH , McKhann GM , Knopman DS , Chertkow H , Hyman BT , Jack CR , Kawas CH , Klunk WE , Koroshetz WJ , Manly JJ , Mayeux R , Mohs RC , Morris JC , Rossor MN , Scheltens P , Carrillo MC , Thies B , Weintraub S , Phelps CH ((2011) ) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7: , 270–279. |

[21] | Folstein MF , Folstein SE , McHugh PR ((1975) ) Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: , 189–198. |

[22] | Perneczky R , Wagenpfeil S , Komossa K , Grimmer T , Diehl J , Kurz A ((2006) ) Mapping scores onto stages: Mini-mental state examination and clinical dementia rating. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14: , 139–144. |

[23] | Lawton MP , Brody EM ((1969) ) Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9: , 179–186. |

[24] | Delbaere K , Close JCT , Taylor M , Wesson J , Lord SR ((2013) ) Validation of the iconographical falls efficacy scale in cognitively impaired older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68: , 1098–1102. |

[25] | Delbaere K , T. Smith S , Lord SR ((2011) ) Development and initial validation of the iconographical falls efficacy scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66A: , 674–680. |

[26] | Hollman JH , Kovash FM , Kubik JJ , Linbo RA ((2007) ) Age-related differences in spatiotemporal markers of gait stability during dual task walking. Gait Posture 26: , 113–119. |

[27] | Hess RJ , Brach JS , Piva SR , VanSwearingen JM ((2010) ) Walking skill can be assessed in older adults: Validity of the Figure-of-8 Walk Test. Phys Ther 90: , 89–99. |

[28] | Cohen J ((1988) ) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. |

[29] | Hall CD , Echt KV , Wolf SL , Rogers WA ((2011) ) Cognitive and motor mechanisms underlying older adults’ ability to divide attention while walking. Phys Ther 91: , 1039–1050. |

[30] | Muir SW , Speechley M , Wells J , Borrie M , Gopaul K , Montero-Odasso M ((2012) ) Gait assessment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: The effect of dual-task challenges across the cognitive spectrum. Gait Posture 35: , 96–100. |

[31] | Brach JS , Studenski S a , Perera S , VanSwearingen JM , Newman AB ((2007) ) Gait variability and the risk of incident mobility disability in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62: , 983–988. |

[32] | Beauchet O , Allali G , Poujol L , Barthelemy JC , Roche F , Annweiler C ((2010) ) Decrease in gait variability while counting backward: A marker of “magnet effect”? J Neural Transm 117: , 1171–1176. |

[33] | Allali G , Kressig RW , Assal F , Herrmann FR , Dubost V , Beauchet O ((2007) ) Changes in gait while backward counting in demented older adults with frontal lobe dysfunction. Gait Posture 26: , 572–576. |

[34] | Beauchet O , Allali G , Berrut G , Hommet C , Dubost VV , Assal FF ((2008) ) Gait analysis in demented subjects: Interests and perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 4: , 155–160. |

[35] | Hunter SW , Divine A , Omana H , Wittich W , Hill KD , Johnson AM , Holmes JD ((2019) ) Effect of learning to use a mobility aid on gait and cognitive demands in people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: Part I - cane. J Alzheimers Dis 71: , S105–S114. |