Predicting Adolescents’ Intentions to Support Victims of Bullying from Expected Reactions of Friends versus Peers

Abstract

Given the crucial role of bystanders in combating bullying in schools, there is a need to understand the reasons why children may or may not intervene on behalf of a victimised peer. The aim of the present study was to explore the association between children’s expectations of general peer reactions versus the reactions of their friends on three subtypes of victim support: consoling the victim, addressing the bully, and getting adult help. A sample of 630 students (297 girls; 333 boys, Mage = 12.5) from three public secondary schools in Germany completed a 30-item questionnaire measuring expected peer reactions, expected friend reactions, past victim support experiences, and intentions to support victims. Results revealed the more influential role of expected reactions of friends over general peers in predicting victim support with expected negative consequences from friends reducing children’s willingness to engage in victim helping, irrespective of the three sub-types of support studied. Expected negative outcomes from peers were also found to significantly affect students’ intentions to approach a teacher for help. Boys were found to be more concerned about their friends’ and peers’ reactions to victim support than girls. The findings are discussed in relation to bystanders’ willingness to offer victim support and associated practical implications for addressing the widespread problem of bullying in schools.

Introduction

Bullying is a form of aggression that is made up of hostile acts that are intentional, repeated over time, and involve a power imbalance between the victim and bully (Olweus, 1978). It can manifest in many ways, often through physical, verbal, relational and cyber sub-types (Macaulay et al., 2022; Smith, 2016). School bullying is now recognised as a global problem that occurs in most classrooms and is a common experience among school students (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Olweus et al., 2019). Bullying victimisation has a negative impact on students’ wellbeing and has been associated with internalising problems including depression, anxiety, withdrawal, loneliness, and externalising issues (e.g., Hawker &; Boulton, 2000; Perren et al., 2013; Reijntjes et al., 2010). Research in this area often categorises distinct roles based on theoretical assumptions and arbitrary cut-off scores. For example, one study based on a large sample with students from six different European countries identified four classes: non-involved, mild bully-victims, bully-victims, and mainly perpetrators (Schultze-Krumbholz et al., 2015). Since school bullying has been recognised as a group phenomenon, and largely due to the participant role approach of Salmivalli et al. (1996), further attention has been placed on the role of bystanders.

Even though most children attest their anti-bullying attitudes and report that they would defend the victim in a bullying situation (Boulton et al., 2002; Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004), they intervene only in a minority of cases. A focus on bystander processes is warranted not least because peer support can help alleviate victims’ suffering (Sainio et al., 2011), so it is important to identify the factors that facilitate or prevent children from doing so. Researchers have examined the role of students’ perceived barriers and identified fear of social reputational damage (e.g., Thornberg, 2007, 2010), relationship status among students (e.g., Bellmore et al., 2012), perceived pressure from significant others (e.g., Boulton et al., 2017; Pozzoli et al., 2012; Pozzoli & Gini, 2013), and gender (e.g., Macaulay et al., 2019; Pozzoli & Gini, 2010; Pozzoli et al., 2012; Thornberg & Jungert, 2014) as being salient. Thornberg (2010) suggested that children’s considerations of social consequences from victims’ help should not be regarded as an isolated process but rather as being influenced by members within the social environment. For example, bystanders are more likely to step in when the victim is regarded as being a friend compared to an acquaintance, a classmate or an unknown student (Bellmore et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2016; Forsberg et al., 2014; Tisak & Tisak, 1996). Thus, it seems worthwhile to further investigate the impact of friends versus neutral peers/classmates on pupils’ victim support behaviours.

Impact of Friends versus Peers on Victim Support Behaviours

Links between bystanders’ expected reactions from others and victim support have been implicated in the literature. Students are skilled enough to recognize that there is a discrepancy between peers’ expected behaviour (i.e., what the peer/s would do) and their prescribed behaviour (i.e., what peer/s should do (Tisak & Turiel, 1988). While seeking to explain the oft-found discrepancy between attitudes and behaviour, Ajzen (1991) proposed the Theory of Planned Behaviour which is the modified version of an earlier model, the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The theory has been employed by researchers largely to investigate the impact of motivational factors on intentions to act as well as on behaviour per se. Theorists believe that actors’ behavioural intentions are the most immediate predictors of behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) and that attitude towards the behaviour, perceived subjective norm, and perceived control over the behaviour also play a role (Ajzen, 1991). Of most relevance to the present study, perceived subjective norm is a social-cognitive element that represents an individual’s perception of how significant other people expect he/she should act in a specific situation. To relate the psychological theory to empirical research, Rigby and Johnson (2006) assessed the role of students’ perceived expectations from parents, friends, and teachers on their willingness to support a victimised peer. The authors found that parental and friend expectations significantly predicted intentions to victim support. More importantly, expected friends’ reactions turned out to be a greater predictor than expected parents’ reactions. Thus, bystanders’ expected reactions from others can influence victim support.

In addition, Pozzoli and Gini (2012) showed that expectations about peer and parental responses significantly predicted children’s’ intervening behaviours in a bullying conflict. Studies have also shown that expectations about peer responses can influence diverse bullying related behaviour; Boulton et al. (2017) found that expected peer disapproval was the main reason why victimised students refrain from seeking teacher help, and Boulton (2013) reported that early adolescents believed that associating with victims leads bullies to consider them as targets. This suggests that children’s anticipated costs of peer disapproval may override the positive effects of putting an end to peer victimisation. These findings highlight not only how salient such fears can be, but also how prevalent these beliefs are among the student population. While Pozzoli and Gini (2012) addressed only generic peers in their research, they recommended their findings be extended by exploring peer pressure at a more fine-grained level. They suggested that researchers should test for friend and non-friend (generic peer) pressures; thus, the present study will investigate specific bystander influence by distinguishing between participants’ expected friend reactions and their expected peer reactions in the prediction of provictim behaviours.

While much of the past literature has explored victim defending as a generic construct (e.g., Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004; Pöyhönen et al., 2010), some studies have acknowledged the theoretically and practically meaningful subdivision of the ‘overall defending’ construct. For instance, Reijntjes et al. (2016) assessed ‘bully-oriented’ (focussed on getting the bully to stop) and ‘victim-oriented’ support (focussed on supporting the victim) separately. However, in their study victim-oriented defending comprised two types of support: support directly addressed to the victim (e.g., consoling, saying not to worry about the incident) and support via asking an adult to help. Similarly, van der Ploeg et al. (2017) evaluated different types of victim-oriented (comfort the victim, encourage the victim to disclose bullying) and bully-oriented (tells others to stop the bullying) support behaviours which were amalgamated into one composite ‘defending variable’. Even though their findings indicated that affective empathy and self-efficacy predicted defending behaviour over time, it remained obscured which factor is more (or less) required in the prediction of a particular sub-type of helping behaviour. As such, van der Ploeg et al. (2017) suggested that employing separate measures for distinct types of victim support would aid a deeper understanding. Furthermore, Kanetsuna et al. (2006) found that bystanders themselves differentiate between multiple victim support strategies, including to take direct action against bullies, seeking help (from teachers, parents, and others), and supporting the victim. Based on this body of work and the recommendation of its authors, the present study subdivided generic victim defending to aid understanding of the processes involved in bystanders’ decision making and advance knowledge of the unique links between prominent factors in the victim support context.

Another key reason for subdividing general victim support into more specific types of help can be attributed to potential gender differences in this context. Overall, studies tend to show that girls are more inclined to help victims and they also intervene more frequently in bullying situations than boys (Macaulay et al., 2019; Pozzoli et al., 2012; Reijntjes et al., 2016; Salmivalli et al., 1996; Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004; Thornberg, 2010; Thornberg & Jungert, 2014). Yet, the question about why girls and boys behave differently in a bullying event is still not answered. Archer and Parker (1994) attempted to explain the gender heterogeneity by suggesting that such differences, observed in response to aggression, may stem from the different reproductive strategies of the two genders. That is, girls tend to exhibit more expressive responses to bullying and report being more upset and more emotionally affected, and this manifests in more sympathetic attitudes towards victims. For instance, compared to boys, girls experience more anger, sadness and empathy in response to same-sex bullying (Hektner & Swenson, 2011; Sokol et al., 2015). Boys, on the other hand, seem more inclined to instrumental responses (addressing the bully/ies directly) and report a higher willingness to action, which may stem from their greater aspiration to be in control (Menesini et al., 1997; Reijntjes et al., 2016).

The Role of Gender and Victim Support Behaviours

The literature reveals some inconsistencies regarding the two genders’ involvement in victim defending behaviours. For example, some researchers report, in situations involving physical harassment, it was usually boys who intervened physically to oppose the aggressor in order to protect the victim (Reijntjes et al., 2016; Thornberg, 2010). This is in line with the gender stereotype of boys being strong and showing a preference for fighting that is supported by observational data (Boulton, 1993). Furthermore, in contrast to Thornberg (2010), Trach et al. (2010) found that girls were more likely than boys to address the bully directly. Moreover, some evidence has shown that girls, compared to boys, are more influenced by contextual factors but not particularly by classroom norms (Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004). Further research is required to generate more precise indications in terms of the heterogeneity among genders and its effect on specific helping behaviours. Hence, when summarising the evidence on gender effects across existing studies it becomes apparent that girls are generally more inclined to engage in generic victim support than their male counterparts. However, the present study will explore if this trend holds across specific support behaviours.

The Present Study

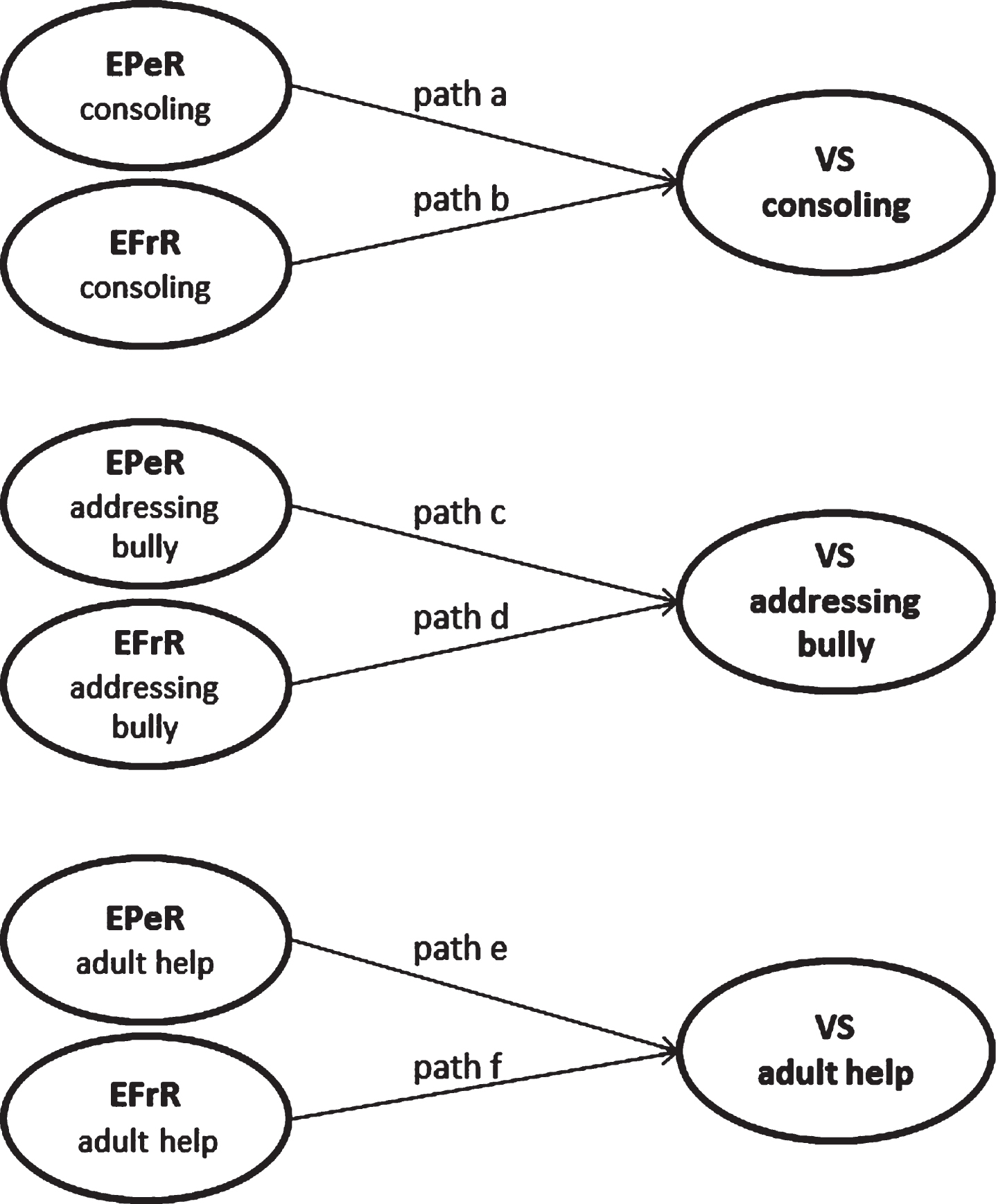

Studying specific sub-types of victim support behaviours in relation to expected negative outcomes from defending and include them as separate constructs in one structural model would also help advance understanding on victim defending. Hence, the theoretical model we propose here (Figure 1) illustrates the pathways that could link the predictors i) expected peer reactions, and ii) expected friend reactions to three specific helping behaviours: consoling the victim, addressing the bully, and getting adult help. In addition, to address the heterogeneity among boys and girls, we tested the original model separately for girls and boys. Table 1 provides a description of the constructs included in the model, and their operationalisation is explained in the Method section.

Figure 1

The Theoretical Model Illustrating the Pathways from Expected Peer and Expected Friend Reactions to Predict three Types of Victim Support

Note. EPeR = Expected Peer Reactions; EFrR = Expected Friend Reactions; VS = Victim Support

Table 1

Describing the Factors Illustrated in the Theoretical Model

| Factor label | Description |

| EPeR consoling | Expected peer reactions if supporting a victim by consoling him/her |

| EFrR consoling | Expected friend reactions if supporting a victim by consoling him/her |

| EPeR addressing bully | Expected peer reactions if supporting a victim by addressing the bully/ies |

| EFrR addressing bully | Expected friend reactions if supporting a victim by addressing the bully/ies |

| EPeR adult help | Expected peer reactions if supporting a victim by getting adult/teacher help |

| EFrR adult help | Expected friend reactions if supporting a victim by getting adult/teacher help |

| VS consoling | Intentions to victim support by consoling |

| VS addressing bully | Intentions to victim support by addressing the bully/ies |

| VS adult help | Intentions to victim support by getting adult/teacher help |

The main aim of the present study, then, was to test the unique contribution of i) expected peer reactions and ii) expected friend reactions in predicting intentions to victim support by (a) consoling, (b) addressing the bully, and (c) getting adult help. A subordinate aim of the current study was to test whether the findings generated by the original model (for the overall participant sample) would differ from gender specific results.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data were collected from 630 students (297 girls and 333 boys, Mage = 12.5, SDage = 1.5) from three public secondary schools in Germany. Ethnicity data were not gathered at the request of the schools. Data were collected on a whole class basis, after informed consent was obtained from headteachers, parents/guardians, and the students completing the questionnaire. Participants were given a questionnaire and were seated to ensure privacy. To encourage honest and considered responses, the researcher reiterated it was not a test, and the students could take their time to complete the questionnaire. The confidentiality of the responses and right to withdraw were highlighted to students before completing the questionnaire. Approval for the study was received from the local Ethics Committee.

Participants were provided with a definition of bullying (Olweus, 1993) and were then invited to complete the questionnaire. Although present at all times, teachers took no active role in data collection.

Measures

A 30-item questionnaire was developed by the lead author; an experienced German teacher screened the wording of the items to assure the adequacy of the language in order to cater for students’ diverse education standards. To measure participants’ expected peer and friend reactions, scales were developed to tap students anticipated general peers’ reactions if they would support a victimised peer: expected peer reactions and expected friend reactions. The three outcome variables (consoling the victim, addressing the bully, getting adult help) in the hypothesised model were operationalised as participants’ intentions to support a victimised peer in one of the three ways specified. In order to do this, two new measures were designed, the past victim support experiences scale and the intentions to victim support scale which together generated the data that ultimately constituted the outcome variables employed in the model. The outcome variables were operationalised by combining the score from the past victim support experiences scale and the intentions to victim support scale for each outcome variable.

Expected Peer Reactions (EPeR). The scale consisted of three sub-scales: consoling the victim, addressing the bully, and getting adult help. Each sub-scale consisted of four items to supplement the lead sentence. The EPeR consoling sub-scale read: “If I helped someone who was being bullied to feel better about themselves, other pupils would. . . ”. In the EPeR addressing the bully sub-scale and the EPeR getting adult help sub-scale the lead sentence would read, “If I helped someone who was being bullied by trying to stop the bullies doing it, other pupils would. . . ”, and “If I helped someone who was being bullied by getting an adult to help, other pupils would. . . ”, respectively. The four items that followed each sub-scale had five response options: two graded negative statements (1 = like me a lot less; 2 = like me less), one neutral statement (3 = no change) and two graded positive statements (4 = like me more; 5 = like me a lot more). Table 2 provides a full list of the response items, which were identical for all three sub-scales. Scores were calculated by averaging participant’s responses across the four items pertaining to each type of support. High scores represented more socially approving (positive) reactions for providing support to a victim. Cronbach’s alpha was high for each EPeR sub-scale: consoling (0.87), addressing the bully (0.88), and getting adult help (0.91).

Table 2

Response Items to Supplement the Lead Sentence in each of the Three Sub-Scales1 Pertaining to the Expected Peer Reactions and Expected Friend Reactions Scale

| Response items |

| 1. liked me a lot less, liked me a bit less –NO CHANGE - liked me a bit more, liked me a lot more |

| 2. thought a lot I was a silly person, thought a bit I was a silly person –NO CHANGE - thought a bit I was a sensible person, thought a lot I was a sensible person |

| 3. thought a lot I was a weak person, thought a bit I was a weak person –NO CHANGE - thought a bit I was a strong person, thought a lot I was a strong person |

| 4. would want to spend a lot less time with me, would want to spend a bit less time with me –NO CHANGE - would want to spend a bit more time with me, would want to spend a lot more time with me |

Note. 1consoling, addressing the bully, getting adult help.

Expected Friend Reactions (EFrR). Expected friend reactions was measured in the same way as described above for expected peer reactions, with four items measuring each of the three sub-scales: consoling the bully, addressing the bully, and getting adult help. That is, the content of the items was identical as reported above but the ‘other pupils’ was substituted with ‘friends’. The response options were identical with those utilised for expected peer reactions, reported in Table 2. Higher scores indicated more socially approving (positive) reactions for providing support to a victim. Cronbach’s alpha was high for each EFrR sub-scale: consoling (0.87), addressing the bully (0.89), and getting adult help (0.89).

Past Victim Support Experiences Scale. This was assessed with a 3-item measure whereby each item pertained to one of the three types of help. Consoling the victim was measured with, “In the past, how often did you help someone who was being bullied to feel better about themselves?”, addressing the bully with “In the past, how often did you help someone who was being bullied by trying to stop bullies doing it?”, and seeking adult help with “In the past, how often did you help someone who was being bullied by getting an adult to help?”. Items were scored on a 4-point scale from 1 (never) to 4 (all of the time), with higher scores indicating a higher frequency of past victim support. Cronbach’s alpha revealed good reliability 0.75.

Intentions to Victim Support Scale. This was assessed with a 3-item measure whereby each item pertained to one of the three types of help. Intentions to console the victim was measured with “In future, when I witness a peer who is being bullied, I will comfort him/her”, addressing the bully with “In future, when I witness a peer who is being bullied, I will try to stop the bullies doing it” and seeking adult help with “In future, when I witness a peer who is being bullied, I will get an adult to help him/her”. Items were scored on a 4-point scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 4 (very likely), with higher scores indicating a higher willingness to support a victimised peer in the future. Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable for short scale 0.63.

Statistical Analyses

To identify the relative predictive contribution of expected friend reaction and expected peer reactions on three victim support behaviours, the present study employed structural equation modelling (SEM) to test the proposed theoretical model. Prior to specifying these models, we computed the unconditional intraclass correlations (ICC), one for each of our dependent variables. This is a necessary step in determining if the hierarchical nature of our data (i.e., children were nested into schools) would or would not need to be accounted for in our models. If there was proportionally ‘a lot’ of similarity in the scores in a dependent variable within each school relative to between-school similarity, then a multi-level models would be appropriate for that dependent variable because the scores within each school would not be independent of each other, as they should be in all regression-based analysis. The ICCs were 0.01 for addressing the bully, 0.03 for getting adult help and 0.02 for consoling the victim. As these were all low and below the usually accepted criterion of 0.05, this indicated that multi-level models were not needed. Three models were scrutinised: one for the overall participant sample, one for female participants only, and another one for male participants only. The construct validity and dimensionality of the models was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with multiple likelihood robust estimation in Mplus version 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010).

Model fit CFA and SEM were determined by assessing consistency on a range of goodness-of-fit indices (Boduszek & Debowska, 2016). Five fit indices are reported for all models: the Chi-Square test (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990) with 90%confidence intervals (90%CI), and the standardised root-mean-square residual (SRMR; Bentler, 1995). Good model fit is assessed through a non-significant χ2 test. However, this method is sensitive to sample size, and so the CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR are also considered as more reliable fit indices for the model. Fit indices range from 0 to 1. Recommended good fit cut-off values should be above 0.95 for CFI and TLI (or >0.90 for acceptable fit: Bentler, 1990), and less than 0.05 for RMSEA and SRMR (with values below 0.08 as reasonable: Browne & Cudeck, 1989).

Results

The study sought to test the unique effect of participants’ i) expected peer reactions, and ii) expected friend reactions in predicting their intentions to three types of support: consoling the victim, address the bully/ies, and get adult help. Table 3 displays the means and standard deviations for all measures and the correlations between the two predictors (EPeR, EFrR) and the three sub-types of victim support, separately (consoling the victim, stopping the bully and getting adult help). The positive zero order correlations between the two factors expected friend reactions and expected peer reactions varied by type of support. They were for consoling 0.38, for addressing the bully 0.52, and for getting adult help 0.54, all p < 0.01. Overall, these moderate to large associations indicate a significant overlap between the predictors which is not surprising as both friends and general peers belong (beside the family) to children’s closest environment where they play a pivotal role. The correlations between each of the factors (friend and peer) and each subtype of victim support revealed noteworthy differences. This was most evident for consoling where the association between friend expectations and this type of support was statistically significant (0.21 at p < 0.01) whereas the correlation between peer expectations and consoling was not (0.07).

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics and Inter-Correlations between all Variables by Type of Support

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1. Gender | 1 | |||||||||

| Consoling the victim | ||||||||||

| 2. EPeR | –0.06 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. EFrR | 0.09* | 0.38** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. VS | 0.17** | 0.07 | 0.21** | 1 | ||||||

| Addressing the bully | ||||||||||

| 5. EPeR | –0.07 | 0.66** | 0.40** | 0.08* | 1 | |||||

| 6. EFrR | 0.05 | 0.43** | 0.72** | 0.21** | 0.52** | 1 | ||||

| 7. VS | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.18** | 0.65** | 0.15** | 0.23** | 1 | |||

| Getting adult help | ||||||||||

| 8. EPeR | –0.04 | 0.50** | 0.30** | 0.04 | 0.51** | 0.27** | 0.01 | 1 | ||

| 9. EFrR | 0.10** | 0.40** | 0.50** | 0.12** | 0.34** | 0.53** | 0.02 | 0.54** | 1 | |

| 10. VS | 0.04 | 0.11** | 0.14** | 0.42** | 0.07 | 0.13** | 0.26** | 0.29** | 0.32** | 1 |

| Mean | 10.01 | 10.96 | 2.49 | 9.97 | 11.01 | 3.03 | 8.85 | 9.67 | 2.79 | |

| SD | 2.25 | 2.15 | 0.70 | 2.43 | 2.37 | 1.16 | 2.51 | 2.11 | 1.03 |

Note. EPeR = Expected Peer Reactions; EFrR = Expected Friend Reactions; VS = Victim Support. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Results for Overall Sample Model

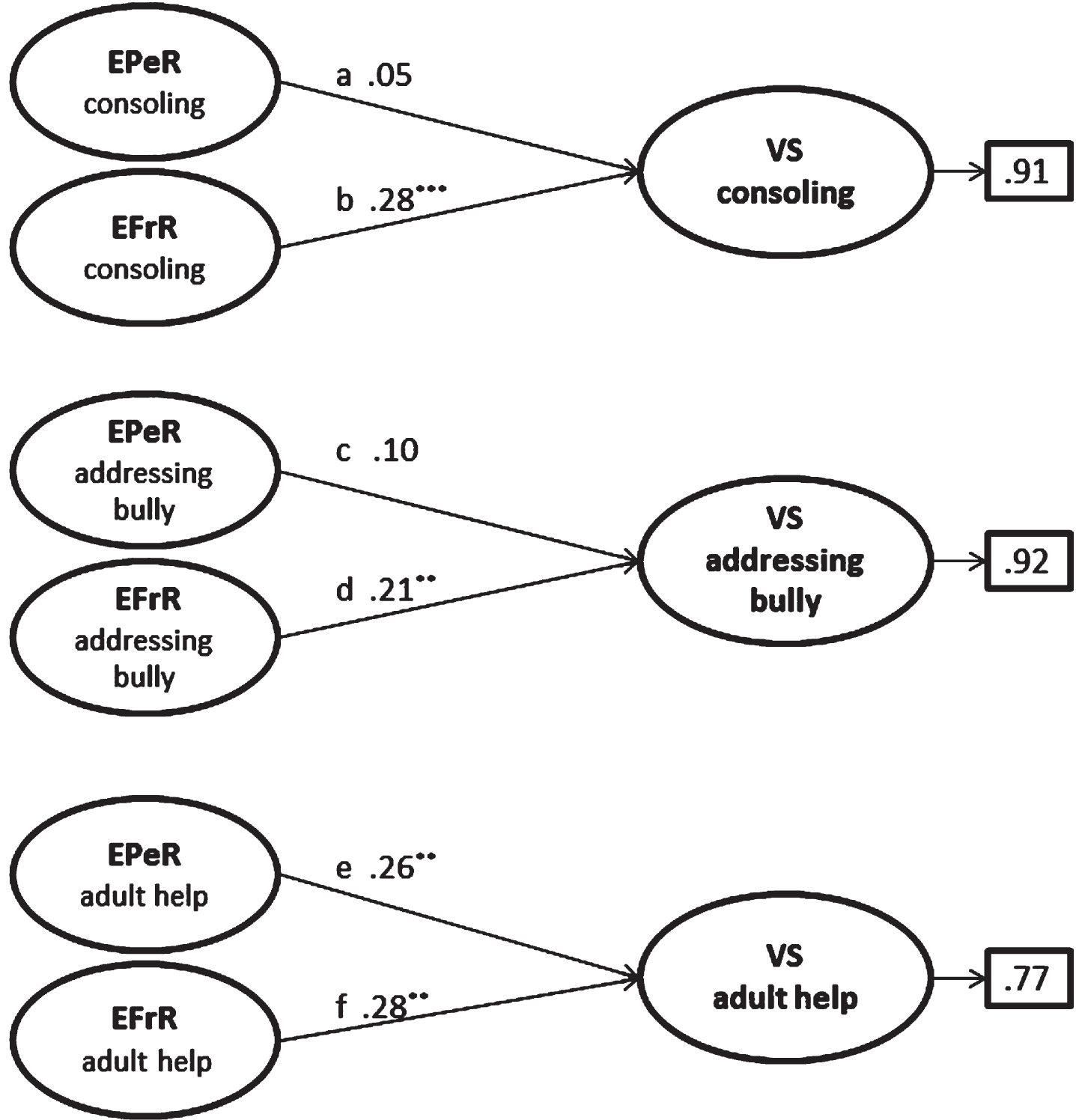

Expected peer reactions (EPeR) and expected friend reactions (EFrR) scores were included as exogenous latent variables (predictors) for each type of help separately. Victim support represented the endogenous latent variable (outcome variable) specified, again, in correspondence which each sub-type of help tested. The assessment of the overall fit of the model yielded the following SEM statistics χ2 (381) = 1355.87, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06 [90%CI = 0.06/0.07], and SRMR = 0.05 indicating an acceptable fit of the model with the data. The standardized path coefficients for the six predictions tested in the model are presented in Figure 2

Figure 2

Structural Equation Model of Expected Peer/Friend Reactions Predicting three Types of Victim Support. Path Coefficients Represent Standardised Values

Note. EPeR = Expected Peer Reactions; EFrR = Expected Friend Reactions; VS = Victim Support. a –f = pathways; **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

For getting adult help support, results showed (path e) that EPeR to this type of help uniquely predicted a student’s intention to enact this behaviour (p < 0.01). For the peer related pathway (path c), results revealed that EPeR did not emerge as a significant predictor of students’ intentions to support a victimised peer by addressing the perpetrator/s. However, a closer inspection of the zero-order correlation between EPeR and addressing the bully suggested a significant (albeit small) association between these two variables (r = 0.15 at p < 0.01). With regard to consoling the victim EPeR did not predict students’ future intentions to provide emotional support to victims of bullying.

SEM results show that irrespective of the subtypes of victim support tested, EFrR emerged as a significant predictor of the three help behaviours (see Figure 2). Findings revealed that path b emerged as the strongest association among the friend related links in the model (p < 0.001), indicating that perceptions of reactions from friends to consoling a victim play a major role in predicting children’s willingness to engage in emotional helping behaviours. With regard to support via addressing the bully (path d) model results showed that EFrR uniquely contributed to students’ intentions of this victim support strategy (p < 0.01). As for the third sub-type of support investigated, which was getting adult help, a significant relationship emerged between the corresponding latent variables (path f) indicating that students’ expected friend consequences significantly predicted their intentions to ask a teacher (or other trusted adult) for help (p < 0.01). Taken together, this suggests that students’ provictim behaviours are substantially influenced by the expected reactions of significant other people, specifically by their friends. Results showed that irrespective of type of support, the associations between EFrR and victim support were stronger than those between EPeR and victim support. In terms of getting adult help both EFrR and EPeR significantly contributed to the model. EFrR, however, was a slightly better predictor than EPeR.

As for the amount of variance accounted for by each predictor in the outcome variable, R2 values indicated that the model explains 9%of the variance for consoling, 8%for stopping the bully, and 23%for getting adult help. So far, consistent across all three types of help, the model showed that students’ EFrR were positively associated with victim support behaviours. This indicates that expected negative friend reactions predicted weaker intentions in students to support a victimised peer.

Results for Gender Specific Models

To investigate gender differences, the author followed Thornberg and Jungert (2013) and tested the original model for boys and girls separately (see Figures 3 and 4, respectively). Model-fit statistics for the boys’ sample (n = 333) χ2 (381) = 853.91, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06 [90%CI = 0.06/0.07], SRMR = 0.06 and the girls’ sample (n = 297) χ2 (381) = 1038.33, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.08 [90%CI = 0.07/0.08], SRMR = 0.07 dropped slightly, but they still indicated an acceptable fit with the current data set.

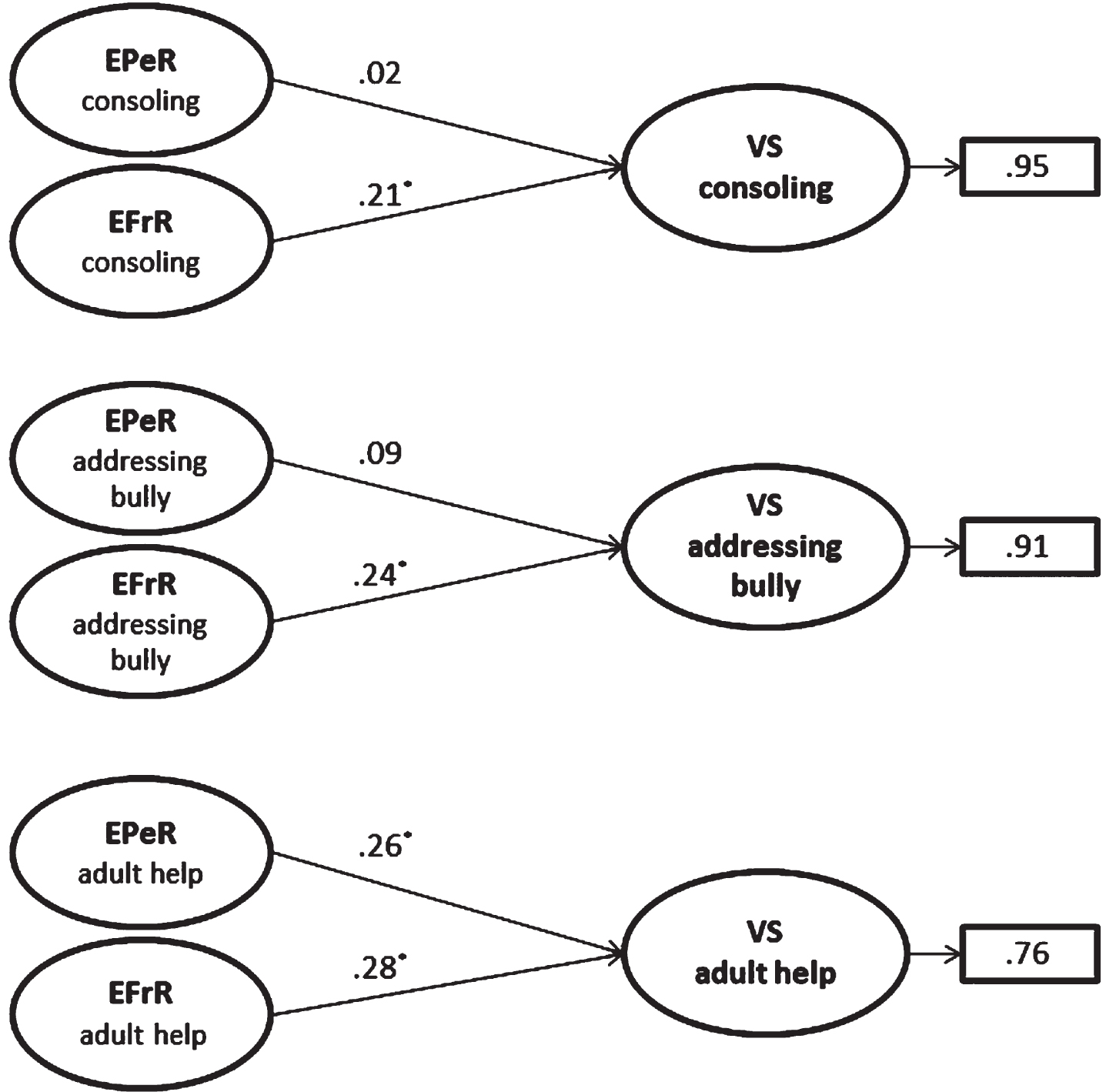

Figure 3

(Boys) Structural Equation Model of Expected Peer/Friend Reactions Predicting three Types of Victim Support. Path Coefficients Represent Standardised Values

Note. EPeR = Expected Peer Reactions; EFrR = Expected Friend Reactions; VS = Victim Support; *p < 0.05.

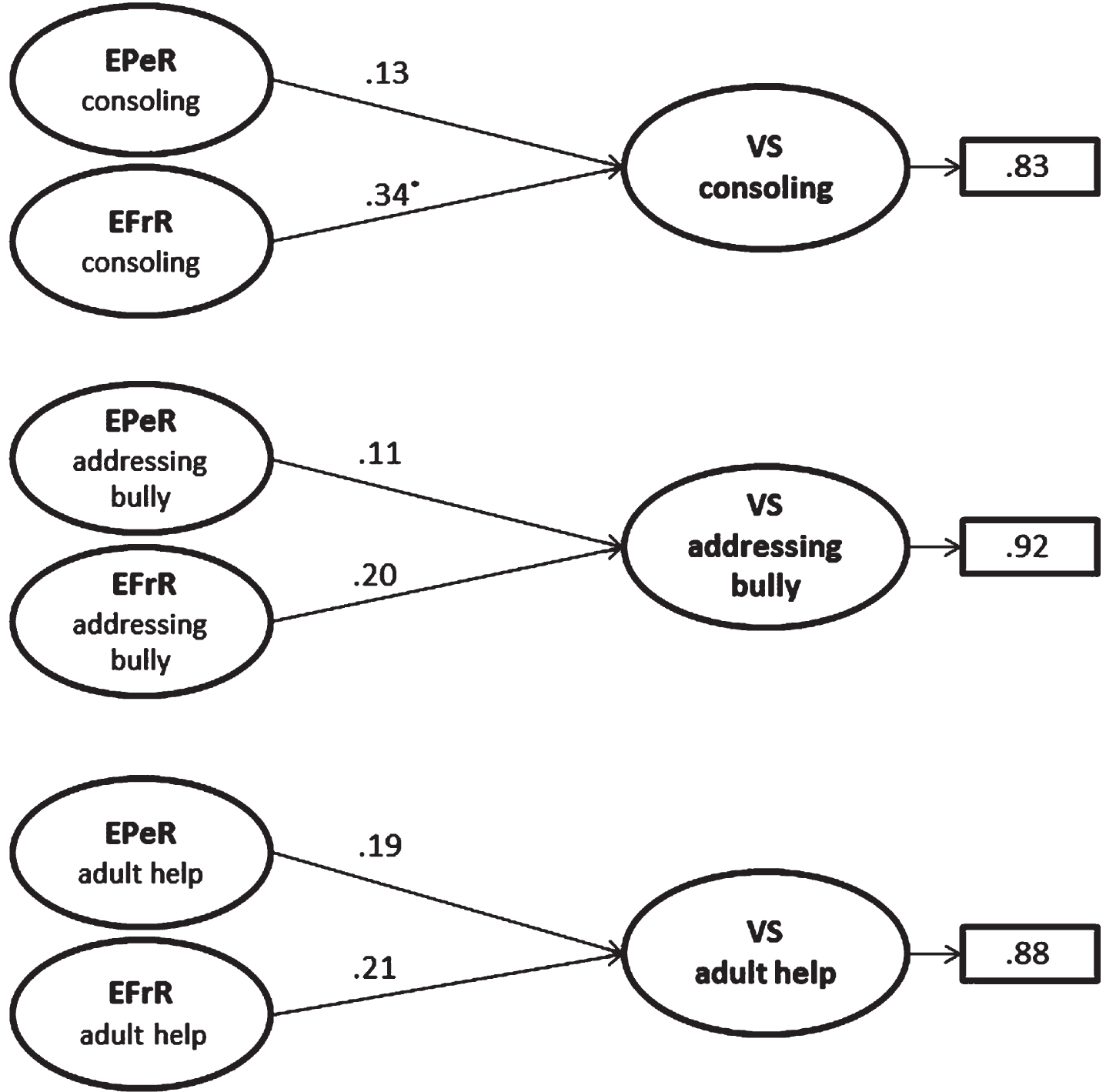

Figure 4

(Girls) Structural Equation Model of Expected Peer/Friend Reactions Predicting three Types of Victim Support. Path Coefficients Represent Standardised Values

Note. EPeR = Expected Peer Reactions; EFrR = Expected Friend Reactions; VS = Victim Support; *p < 0.05.

The standardised path coefficients for the boys’ sample are illustrated in Figure 3 and findings revealed that the pattern of significant positive relationships, which was found in the overall model, was precisely replicated. That is, irrespective of the three subtypes of victim support tested, for boys, expected friend reactions significantly predicted the corresponding help behaviours. In terms of the associations pertaining to general peers’ reactions, only the prediction concerning adult help support reached statistical significance. Expected friend reactions was (again) a slightly better predictor of intentions to get adult support than expected peer reactions. Overall, this indicates that for boys their friends’ responses to victim defending appear to matter more in this context than potential disapproval/approval from neutral peers.

As can be seen in Figure 4, for the girls’ sample only one significant association emerged which belonged to support by consoling the victim. More specifically, in the girls’ model, expected friend reactions for victim consoling emerged as a significant predictor of this subtype of help. This finding demonstrated that this relationship was not only considerably stronger (0.34 significant at p < 0.05) than that observed in the boys’ model (0.21 significant at p < 0.05), but it also turned out to be the strongest association among all the predictions tested in this study. With regard to support solicited by addressing the bully and requesting adult help, the findings revealed that girls are less affected by their friends’ consequences compared to their male counterparts. Interestingly, the victim support prediction pattern observed in the boys’ model did not hold in the girls’ model.

The findings from the gender specific tests have shown that boys and girls do differ substantially in aspects related to perceptions of friend and (partly) peer reactions. The proportion of variance explained by the predictors in the outcome variables regarding the two gender specific models were for boys, 5%for consoling, 9%for addressing the bully, and 24%for getting adult help. The percentages for girls were 17%for consoling, 8%for addressing the bully, and 12%for getting adult help. That is, in the boys’ model the highest proportion of variance accounted for by the predictors was observed for getting adult help support whereas in the girls’ model the largest proportion was found for consoling the victim.

Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to explore whether students’ expected peer and friend reactions to their pro-victim actions would pose a barrier to their future victim helping behaviours, which were specified as three separate types of support (consoling the victim, addressing the bully/ies, and getting adult help).

The findings showed that expected friend reactions to specific subtypes of victim support uniquely predicted intentions to engage in each helping behaviour studied. That is, a clear pattern emerged from the model showing that the proposed associations, between expected friend reactions and victim support, were significant across all three support strategies: consoling, addressing the bully/ies, and getting adult help. The findings suggest that whether bystanders intervene on behalf of the victim may depend on whether they expect approving or disapproving reactions from their friends. In other words, this finding indicates that children who expect positive reactions from friends (e.g., respect), increased liking or friendship consolidation will be more inclined to defend a victimised peer. Conversely, students will be less likely to offer support to victims when they perceive that siding with a ‘weak’ peer may lead to friends’ disapproval and could possibly damage their social standing among their friends. Our findings indicate that if children fear some kind of social costs such as being liked less or being regarded as a ‘weak person’ by friends, or even a loss of friendship, they will most likely deny support to the victim. Prior research suggests that friendship is related to morality and helping, particularly when the victim happens to be a friend (Forsberg et al., 2014), and friends have been found to serve as moral role models which then leads to adaptation processes to match one’s friend’s behaviour (Caravita et al., 2014) including his/her bullying attitudes (Pozzoli & Gini, 2013). The present findings show that friendship is an important factor which can influence bystanders’ victim support behavioural intentions as well.

The findings on expected peer reactions revealed a significant effect for ‘getting adult help’ support. The outcome suggests that perceived negative peer reactions predicted weaker intentions in students to approach a teacher for help. This result confirms previous findings by Pöyhönen et al. (2012) who reported that students who anticipate a negative outcome from peers (if supporting the victim) such as a decline in reputation refrain from helping, consoling and addressing the bully. Conversely, those who expected approval from the peer group and a boost in their social standing would engage in victim support behaviours. By subdividing ‘generic help’ in the present study, analyses generated more detailed information about the beliefs that students hold towards each subtype of help. In other words, with the current model we were able to elucidate that expected peer reactions did not predict victim support by consoling and addressing the bully. Why these two pathways did not reach statistical significance in the proposed model remains unanswered and we offer suggestions for why that might have been the case.

It is possible that pupils fear being ridiculed by peers if they seek teacher support, as this may bring about the reputation of a tell-tale among classmates. This can then lead to additional, aggravated consequences such as subsequent exclusion from the peer group. For example, Thornberg (2010) found that reporting peer aggression to a teacher was associated with social consequences by bystanders since this was regarded as squealing. Another possible explanation is that students tend to refrain from requesting adult support as they might believe they are capable enough and should therefore deal with disagreements among peers autonomously (e.g., Nucci & Nucci, 1982). Indeed, it has been suggested that early adolescent development implicates an increased desire for autonomy and peer orientation, and it seems that concerns about peer approval/disapproval peak at this developmental stage (Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Our results are important and confirm that a person’s intent to act may be motivated by perceived expectations of significant people in the environment (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). They corroborate one of the key components in Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behaviour, which highlights the role of normative beliefs that an individual holds and which ultimately contributes to his/her actions.

That one of the three peer related pathways (getting adult help) in the model was significant and the other two (consoling, addressing the bully) were not, is a key finding in this study. It provides support for the present theoretical approach to consider each subtype of help as a conceptually separate construct, instead of amalgamating help into one single generic factor. ‘Getting adult help’ seems to evoke greater salience in the current participant sample than the other two strategies of victim support tested. These results are important as they raise further questions about why getting adult help appears to stand out from other types of support. In contrast to the three dimensions of victim support in the present study, Reijentjes and colleagues (2016) included the option of seeking adult help together with consoling in one factor which they conceptualised as ‘victim-oriented defending’. The present findings highlight that adult help plays a significant role in the victim support context. For example, in incidents where the perpetrators are extremely aggressive, consoling (i.e., ‘victim-oriented’ defending) and stopping the bully (i.e., ‘bully-oriented’ defending) may be unsafe to pursue, so asking an adult for help becomes crucial for victims and bystanders, alike. Not only will the victim be helped (Smith et al., 2004) but it can also be a relief for bystanders, who may feel distressed by an inner conflict when they would like to help but feel unable to act upon their empathy or moral attitude. Therefore, turning to an adult for support can help resolve this moral dilemma and perhaps motivate passive bystanders to become defenders.

With regard to the comparison between expected consequences from friends and expected consequences from general peers, expected friend reactions was a stronger predictor of victim help than expected peer reactions, irrespective of type of support. Even for the most salient helping strategy, which was “getting adult help”, and where both factors emerged as significant predictors of this behaviour, the friend path (path f in the model, Figure 2) was stronger than that for peers (path e in the model, Figure 2). This result is not surprising from a relationship status point of view as friendships are generally valued more highly than general peer relationships. The present findings are consistent with the idea that motivation to sustain friendship is likely to yield favouritism toward friends versus non-friends (Hoffman, 2000) as an individual may feel a greater moral obligation to a friend than to other peers. In the specific context of bystander engagement in victim support, the superiority of friends over general peers is an important new insight.

Overall, the general pattern of our results corroborates the influential role of friends by showing that the importance of friends exceeds that of ordinary peers. For the pupils in the current study, this suggests that a friend’s opinion if they anticipate consequence matters more than that of a typical peer. This means that with regard to the victim defending context, students seem more concerned about being disliked or rejected by their friends than by their peers. Researchers must be aware that victim defending cannot solely be explained by an individual’s perceived friends’ consequences. Prior research has emphasised the importance of quality relationships for victim defending in general, irrespective of the relationship status (friends or non-friends; Thornberg et al., 2017). Thornberg et al. (2017) reported that in classrooms where student-student relationship quality was high (characterised for instance by kindness and caring attributes) pupils were more inclined to engage in victim defending even when their moral disengagement was high.

To investigate whether gender would moderate the initially generated outcomes, the theoretical model was tested for boys and girls separately. As expected, the gender specific analyses revealed variation between boys’ and girls’ intentions to intervene on behalf of a victimised peer. Irrespective of the three types of support tested, boys’ expected friend reactions was predictive of the corresponding support behaviours. In other words, the outcome suggested that boys who expected that supporting a victim may lead to decreased liking by one’s friends, were significantly more likely to disengage from all three sub-types of support. The same was true for the relationship between expected peer reactions and getting adult help. This particular helping strategy stood out in the boys’ model (see Figure 3) as the only path to reach statistical significance. For boys, the findings from the moderation test mirror precisely the pattern of results obtained initially for the whole participant sample in the original model (see Figure 2). This pattern, however, did not hold for the girls’ results (see Figure 4) where only one significant association emerged, namely, expected friend reactions significantly predicted victim consoling.

This finding is important as it highlights the heterogeneity among pupils, and raises our awareness about substantial differences between boys’ and girls’ perceptions of friend and peer consequences in the victim defending context. The moderation effect evident in the girls’ sample for ‘consoling the victim’ is consistent with trends in the extant literature which evidenced that girls are more likely to engage in emotional victim support than boys (Reijntjes et al., 2016). For instance, among the victim-oriented defenders (included consoling and getting adult help) Reijntjes et al. found that over 80%were girls. This tendency has been attributed to girls’ gender specific norms, and stronger nurturing and psychological caring characteristics (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989). Conversely, in the bully-oriented subgroup (stop the bully/ies’ harassment) the majority of defenders were boys, who tend to primarily confront the perpetrators and refrain from comforting the victim. These explanations tie in with other evidence which emphasised both girls’ higher inclination to defend victims (Thornberg & Jungert, 2014) and their higher degree of basic moral sensitivity which contrasts boys’ higher moral disengagement (Thornberg & Jungert, 2013). Based on the present findings, it generally seems that boys are more concerned about potential negative consequences from friends and peers if they anticipate victim support, than girls.

Taken together, the findings of the present study contribute to the broader knowledge on students’ complex decision-making processes by underscoring Boulton et al.’s (2017) research that yielded the first understanding on how adolescents trade off the anticipated personal costs (in their case, peer disapproval) against the most valued collective outcome, which is stopping bullying perpetration in school.

Limitations

Some limitations of the current study need to be noted. The current findings are based on cross-sectional data which do not allow causal relations between the predictors and the outcome variable even though the interpretation of the direction of effects is logically consistent with the underpinning theory (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). In addition, the issue of self-report measures needs to be addressed. While self-reports are viewed as inexpensive, least obtrusive and most efficient, the data can easily be inflated by social desirability bias as individuals tend to make self-favouring attributions (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010). It is also important to note the results reflect intentions, and therefore should be considered on the basis that they may not actually translate into action. Nevertheless, given that participants were asked to provide their subjective perceptions which they may not necessarily express publicly, self-reports are a valuable method that seems appropriate for the assessment of the constructs studied (Newman, 2008). Future research should provide a replication of the current research via a longitudinal design. Researchers could investigate how students perceived negative consequences would manifest over time in actual (un-) favourable behaviours. This would also allow elaboration on whether, and how, victim support (or non-support) experiences encountered across time may affect students’ initial perceptions in this regard.

Another shortcoming of the present research was that the proposed model did not account for age moderating effects. It is possible that the fear of friend/peer disapproval varies as a function of age. So far, the past evidence has been inconclusive. While some studies have shown that victim defending decreases with increasing age (Pozzoli et al., 2012; Pöyhönen et al., 2012), other research did not confirm a link between age and defending (Reijntjes et al., 2016). Hence, further theoretical and empirical work is warranted in order to elaborate the original model and include age as an additional factor.

Implications

The findings of this study have implications for the development of anti-bullying prevention and intervention programmes that, in turn, may guide future practice in schools. They clearly highlight the importance of friends in the victim defending context. They suggest the inclusion of measures in intervention programmes that foster friendship bonds among peers in general, but also with victims. This may also be accomplished, for example, through increased daily teamwork throughout the academic year, not only as ‘a one-off session’ aimed to facilitate social relationships among classmates. The current findings also have implications for general moral values education in schools, as friend loyalty has to be challenged if it conceals personal responsibility and reinforces anti-social behaviour. In addition, assertiveness training on a whole class basis can encourage passive bystanders to stand up for the victim, overcome the fear of potential negative consequences, and resist pressure from friends (or significant others) if they disapprove helping. Past research has shown that initially passive bystanders who were trained in the role of peer supporters can act as a valuable resource for victims of bullying (Cowie, 2000).

Further attention on why the disclosure of bullying and help-seeking is so problematic for students to endorse given that victims (in particular) experience such high levels of distress (Hawker & Boulton, 2000; Reijntjes et al., 2010) is needed. Hence, encouraging bystanders to help disclose witnessed bullying to a trusted teacher, who has more resources per se, is essential. Victims often refrain from speaking out because they feel helpless and ashamed about their humiliating experiences (Hunter et al., 2004). Therefore, future intervention could stress the importance of disclosing bullying incidents and emphasise multiple types of victim support to cater for a diverse bystander audience.

In summary, our findings revealed the perceived superior role of friends over general peers in predicting victim support. More specifically, the findings indicated that perceived negative consequences from friends can pose a barrier to children’s willingness to engage in victim help, irrespective of the three sub-types of support studied.

References

1 | Ajzen, I. ((1991) ). The theory of planned behaviour, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: (2), 179–211. https://10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T |

2 | Ajzen, I. , Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall. |

3 | Archer, J. , Parker, S. ((1994) ). Social representations of aggression in children, Aggressive Behavior 20: (2), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:2%3C101::AID-AB2480200203%3E3.0.CO;2-Z |

4 | Bellmore, A. , Ma, T. L. , You, J. I. , Hughes, M. ((2012) ). A two-method investigation of early adolescents’ responses upon witnessing peer victimization in school, Journal of Adolescence 35: (5), 1265–1276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.012 |

5 | Bentler, P. M. ((1990) ). Comparative fit indexes in structural models, Psychological Bulletin 107: (2), 238. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 |

6 | Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. BMDP Statistical Software. |

7 | Boduszek, D. , Debowska, A. ((2016) ). Critical evaluation of psychopathy measurement (PCL-R and SRP-III/SF) and recommendations for future research, Journal of Criminal Justice 44: , 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.11.004 |

8 | Boulton, M. J. ((1993) ). Aggressive fighting in British middle school children, Educational Studies 19: (1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569930190102 |

9 | Boulton, M. J. ((2013) ). The effects of victim of bullying reputation on adolescents’ choice of friends: Mediation by fear of becoming a victim of bullying, moderation by victim status, and implications for befriending interventions, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 114: (1), 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.05.001 |

10 | Boulton, M. J. , Boulton, L. , Down, J. , Sanders, J. , Craddock, H. ((2017) ). Perceived barriers that prevent high school students seeking help from teachers for bullying and their effects on disclosure intentions, Journal of Adolescence 56: , 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.11.009. |

11 | Boulton, M. J. , Trueman, M. , Chau, C. A. M. , Whitehand, C. , Amatya, K. ((1999) ). Concurrent and longitudinal links between friendship and peer victimization: Implications for befriending interventions, Journal of Adolescence 22: (4), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0240 |

12 | Boulton, M. J. , Trueman, M. , Flemington, I. ((2002) ). Associations between secondary school pupils’ definitions of bullying, attitudes towards bullying, and tendencies to engage in bullying: Age and sex differences, Educational Studies 28: (4), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569022000042390 |

13 | Browne, M. W. , Cudeck, R. ((1989) ). Single sample cross-validation indices for covariance structures, Multivariate Behavioral Research 24: (4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr24044 |

14 | Caravita, S. C. , Sijtsema, J. J. , Rambaran, J. A. , Gini, G. ((2014) ). Peer influences on moral disengagement in late childhood and early adolescence, Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43: (2), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9953-1 |

15 | Chen, L. M. , Chang, L. Y. , Cheng, Y. Y. ((2016) ). Choosing to be a defender or an outsider in a school bullying incident: Determining factors and the defending process, School Psychology International 37: (3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0143034316632282. |

16 | Cornell, D. G. , Bandyopadhyay, S. (2010). The assessment of bullying. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer,&D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective, Routledge, pp. 265–276. |

17 | Cowie, H. ((2000) ). Bystanding or standing by: Gender issues in coping with bullying in English schools, Aggressive Behavior 26: (1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:1%3C85::AID-AB7%3E3.0.CO;2-5 |

18 | Eccles, J. S. , Midgley, C. (1989). Stage/environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for early adolescents. In R. E. Ames,&C. Ames, (Eds.), Research on motivation in education, Academic Press, Vol. 3, pp. 139–181. |

19 | Eisenberg, N. , Mussen, P. H. (1989). The roots of prosocial behavior in children. Cambridge University Press. |

20 | Forsberg, C. , Thornberg, R. , Samuelsson, M. ((2014) ). Bystanders to bullying: Fourth-to seventh-grade students’ perspectives on their reactions, Research Papers in Education 29: (5), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.878375 |

21 | Hawker, D. S. , Boulton, M. J. ((2000) ). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 41: (4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629 |

22 | Hektner, J. M. , Swenson, C. A. ((2012) ). Links from teacher beliefs to peer victimization and bystander intervention: Tests of mediating processes, The Journal of Early Adolescence 32: (4), 516–536. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0272431611402502 |

23 | Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implication for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press. |

24 | Hunter, S. C. , Boyle, J. M. , Warden, D. ((2004) ). Help seeking amongst child and adolescent victims of peeraggression and bullying: The influence of school-stage, gender, victimisation, appraisal, and emotion, British Journal of Educational Psychology 74: (3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099041552378 |

25 | Kanetsuna, T. , Smith, P. K. , Morita, Y. ((2006) ). Coping with bullying at school: Children’s recommended strategies and attitudes to school-based interventions in England and Japan, Aggressive Behavior 32: (6), 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20156 |

26 | Macaulay, P. J. , Betts, L. R. , Stiller, J. , Kellezi, B. (2022). An introduction to cyberbullying. In A. A. Moustafa, (Ed.), Cybersecurity and cognitive science, Academic Press, pp. 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90570-1.00002-4 |

27 | Macaulay, P. J. , Boulton, M. J. , Betts, L. R. ((2019) ). Comparing early adolescents’ positive bystander responses to cyberbullying and traditional bullying: The impact of severity and gender, Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science 4: (3), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-018-0082-2 |

28 | Menesini, E. , Eslea, M. , Smith, P. K. , Genta, M. L. , Giannetti, E. , Fonzi, A. , Costabile, A. ((1997) ). Crossnational comparison of children’s attitudes towards bully/victim problems in school, Aggressive Behavior 23: (4), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1997)23:4%3C245::AID-AB3%3E3.0.CO;2-J |

29 | Menesini, E. , Salmivalli, C. ((2017) ). Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions, Psychology, Health&Medicine 22: (sup1), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740 |

30 | Muthén L. K. , Muthén, B. O. (1998-2010). MPlus user’s guide: Sixth Edition. Muthén & Muthén. |

31 | Newman, R. S. ((2008) ). Adaptive and nonadaptive help seeking with peer harassment: An integrative perspective of coping and self-regulation, Educational Psychologist 43: (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701756206 |

32 | Nucci, L. P. , Nucci, M. S. ((1982) ). Children’s social interactions in the context of moral and conventional transgressions, Child Development 53: (2), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128983 |

33 | Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullying and whipping boys. Hemisphere. |

34 | Olweus, D. , Limber, S. P. , Breivik, K. ((2019) ). Addressing specific forms of bullying: A large-scale evaluation of the Olweus bullying prevention program, International Journal of Bullying Prevention 1: (1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00009-7 |

35 | Perren, S. , Ettekal, I. , Ladd, G. ((2013) ). The impact of peer victimization on later maladjustment: Mediating and moderating effects of hostile and self-blaming attributions, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 54: (1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02618.x |

36 | Pöyhönen, V. , Juvonen, J. , Salmivalli, C. ((2010) ). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying? The interplay between personal and social factors, Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 56: (2), 143–163. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23098039 |

37 | Pöyhönen, V. , Juvonen, J. , Salmivalli, C. ((2012) ). Standing up for the victim, siding with the bully or standing by? Bystander responses in bullying situations, Social Development 21: (4), 722–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00662.x |

38 | Pozzoli, T. , Gini, G. ((2010) ). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 38: (6), 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9 |

39 | Pozzoli, T. , Gini, G. ((2013) ). Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? A multidimensional model, The Journal of Early Adolescence 33: (3), 315–340. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0272431612440172 |

40 | Pozzoli, T. , Gini, G. , Vieno, A. ((2012) ). The role of individual correlates and class norms in defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: A multilevel analysis, Child Development 83: (6), 1917–1931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01831.x |

41 | Reijntjes, A. , Kamphuis, J. H. , Prinzie, P. , Telch, M. J. ((2010) ). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies, Child Abuse&Neglect 34: (4), 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009 |

42 | Reijntjes, A. , Vermande, M. , Olthof, T. , Goossens, F. A. , Aleva, L. , van der Meulen, M. ((2016) ). Defending victimized peers: Opposing the bully, supporting the victim, or both, Aggressive Behavior 42: (6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21653 |

43 | Rigby, K. , Johnson, B. ((2006) ). Expressed readiness of Australian schoolchildren to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied, Educational Psychology 26: (3), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500342047 |

44 | Sainio, M. , Veenstra, R. , Huitsing, G. , Salmivalli, C. ((2011) ). Victims and their defenders: A dyadic approach, International Journal of Behavioral Development 35: (2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0165025410378068 |

45 | Salmivalli, C. , Lagerspetz, K. , Björkqvist, K. , Österman, K. , Kaukiainen, A. ((1996) ). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group, Aggressive Behavior 22: (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1%3C1::AID-AB1%3E3.0.CO;2-T |

46 | Salmivalli, C. , Voeten, M. ((2004) ). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations, International Journal of Behavioral Development 28: (3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488 |

47 | Schultze-Krumbholz, A. , Göbel, K. , Scheithauer, H. , Brighi, A. , Guarini, A. , Tsorbatzoudis, H. , Smith, P. K. ((2015) ). A comparison of classification approaches for cyberbullying and traditional bullying using data from six European countries, Journal of School Violence 14: (1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.961067 |

48 | Smith, P. K. ((2016) ). Bullying: Definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention, Social and Personality Psychology Compass 10: (9), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12266 |

49 | Smith, P. K. , Talamelli, L. , Cowie, H. , Naylor, P. , Chauhan, P. ((2004) ). Profiles of non-victims, escaped victims, continuing victims and new victims of school bullying, British Journal of Educational Psychology 74: (4), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099042376427 |

50 | Sokol, N. , Bussey, K. , Rapee, R. M. ((2015) ). The effect of victims’ responses to overt bullying on same-sex peer bystander reactions, Journal of School Psychology 53: (5), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.07.002 |

51 | Steiger, J. H. ((1990) ). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach, Multivariate Behavioral Research 25: (2), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr25024 |

52 | Thornberg, R. ((2007) ). A classmate in distress: Schoolchildren as bystanders and their reasons for how they act, Social Psychology of Education 10: (1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-006-9009-4 |

53 | Thornberg, R. ((2010) ). A student in distress: Moral frames and bystander behavior in school, The Elementary School Journal 110: (4), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1086/651197 |

54 | Thornberg, R. , Jungert, T. ((2013) ). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement, and defender self-efficacy, Journal of Adolescence 36: (3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003 |

55 | Thornberg, R. , Jungert, T. ((2014) ). School bullying and the mechanisms of moral disengagement, Aggressive Behavior 40: (2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21509 |

56 | Thornberg, R. , Wänström, L. , Hong, J. S. , Espelage, D. L. ((2017) ). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in Sweden: A multilevel analysis, Journal of School Psychology 63: , 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002 |

57 | Tisak, M. S. , Tisak, J. ((1996) ). Expectations and judgments regarding bystanders⪢ and victims ⪡ responses to peer aggression among early adolescents, Journal of Adolescence 19: (4), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1996.0036 |

58 | Tisak, M. S. , Turiel, E. ((1988) ). Variation in seriousness of transgressions and children’s moral and conventional concepts, Developmental Psychology 24: (3), 352. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.24.3.352 |

59 | Trach, J. , Hymel, S. , Waterhouse, T. , Neale, K. ((2010) ). Bystander responses to school bullying: A cross sectional investigation of grade and sex differences, Canadian Journal of School Psychology 25: (1), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0829573509357553 |

60 | Tucker, L. R. , Lewis, C. ((1973) ). Areliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis, Psychometrika 38: (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291170 |

61 | van der Ploeg, R. , Kretschmer, T. , Salmivalli, C. , Veenstra, R. ((1973) ). Areliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis, Psychometrika 38: (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.002 |

Bio Sketches

Hedda Marx, PhD., is a counsellor at the Psychotherapeutic Outpatient Clinic of the Alfred-Adler-Institute Cologne. Her interests are in social and individual psychology, focusing mainly on the evaluation of impact factors in psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Michael J. Boulton, PhD., is an Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Chester, UK. He has research interests in bullying related issues, is recognised as an international expert on bullying among school pupils and has published numerous papers on the topic over 25 years.

Peter J. R. Macaulay, PhD., is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Derby, UK. His main research interests are in social developmental psychology, focusing specifically on teacher’s perceptions towards cyberbullying, children’s bystander behaviour in the online/offline domain, and children’s knowledge of online risks and safety.