Extremist Thinking and Doing: A Systematic Literature Study of Empirical Findings on Factors Associated with (De)Radicalisation Processes

Abstract

The aim of the present literature review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the empirical literature on radicalisation leading to extremism. Two research questions are asked: (1) Under what conditions are individuals receptive to extremist groups and their ideology? (2) Under what conditions do individuals engage in extremist acts? A theoretical framework is used to structure the findings. A systematic literature search was conducted including peer-reviewed articles containing primary qualitative or quantitative data. A total of 707 empirical articles were included which used quantitative or qualitative research methods. The findings clearly indicate that no single factor in itself predicts receptiveness to extremist ideas and groups, or engagement in violent behaviour. Rather, factors at different levels of analysis (micro-, meso- and macro-level) interplay in the radicalisation process.

Introduction

Radicalisation leading to violent extremism has posed pressing societal challenges for decades as it involves human suffering and comes at high financial costs (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2019). This has resulted in a fast-growing number of research publications addressing the questions on how and when radicalisation occurs and under which conditions it results in violence (Schuurman, 2019). We see radicalisation as a process through which individuals - or groups, or institutions - become increasingly motivated to use violent means against members of an out-group or symbolic targets to achieve behavioral change and political goals (Doosje et al., 2016, p. 79). Violent extremism, when individuals have a distinct willingness to use ideology-based violence, is the endpoint of this process (Schmid, 2013, p. iv). From this perspective, radical individuals are not necessarily violent extremists, but violent extremists have all gone through a process of radicalisation. In the present research we provide an overview of the factors which have thus far been shown to play a role in the (de)radicalisation process and violent extremism.

We know that no single profile exists of the person who radicalises to the point of using violence (Horgan, 2017; King & Taylor, 2011). Structural root causes which have been identified (such as poverty, inequality, discrimination) are important, but not sufficient explanations (Horgan, 2008; Schmid, 2013). Indeed, a range of systematic reviews on radicalisation factors have now been published including reviews of protective factors against extremism and violent radicalisation (Lösel et al., 2018, including 17 publications), push, pull and and personal factors leading to behavioural and cognitive radicalisation (Vergani et al., 2020, including 148 publications) factors related to radical attitudes, intentions, and behaviours (Wolfowicz et al., 2020, including 57 publications), risk factors for violent radicalisation among adolescents and young adults (Emmelkamp et al., 2020, including 30 publications); political violence outcomes with a focus on young people below age 30 (Jahnke et al., 2022, including 67 publications).

Notably, these reviews focus on empirical research including quantitative primary empirical data. In the present research we focus on both quantitative and qualitative primary empirical data and thereby aim to provide an overview of all the available empirical primary data. In addition, an increasing number of peer-reviewed publications consist of re-analyses of existing databases. We also include these analyses in our research, which should yield a greater number of research reports.

The Present Study

In order to provide a better understanding of which factors play a role in the radicalisation process and violent extremism, the present research aims to answer the following two research questions:

1. Under what conditions are individuals receptive to extremist groups and their ideology?

2. Under what conditions do individuals engage in extremist acts?

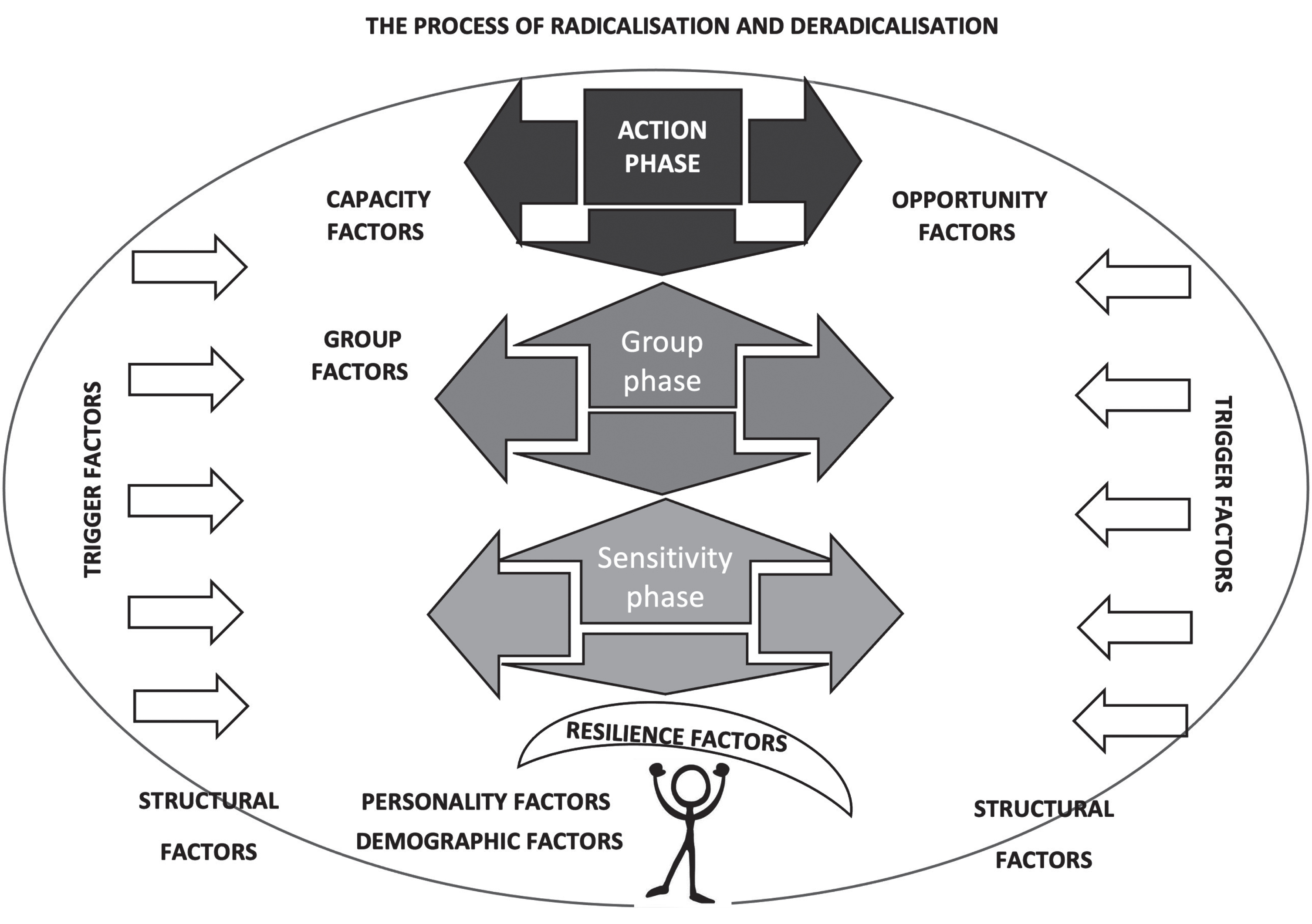

In Figure 1, which is based on Doosje et al. (2016), three phases of radicalisation are shown. The sensitivity phase refers to the period in which a person is receptive for extremist ideology. The group phase takes place after a person joins a radical group, and the action phase is when a person is willing to act on behalf of the group’s ideology. We consider the radicalisation process to be a dynamic, non-linear process. Hence, the arrows indicate that a person can move towards or away from a phase. In addition, various factors are shown that contribute towards further radicalisation or towards deradicalisation. The shield above the person symbolises resilience against radicalisation.

Figure 1

Theoretical Model of (De)radicalization.

Note. Based on Doosje et al. (2016), with three phases (the sensitivity, group and action phase), and various factors that can contribute to an upward movement (towards further radicalisation) and a downward or sideways movement (towards deradicalisation or disengagement). The shield above the individual symbolises resilience against (de)radicalisation.

The two research questions are reflected in this model as the question of susceptibility to extremist ideas and groups coincides with the sensitivity phase and group phase of the model. The question regarding the move to extremist violence concerns (the transition towards) the action phase, either from the group phase. In the model, demographic factors are included, as well as factors at the level of the individual (micro-level, e.g., personality), the group (meso-level, e.g., us vs. them thinking) and societal level (macro-level, e.g., repression by state authorities).

Method

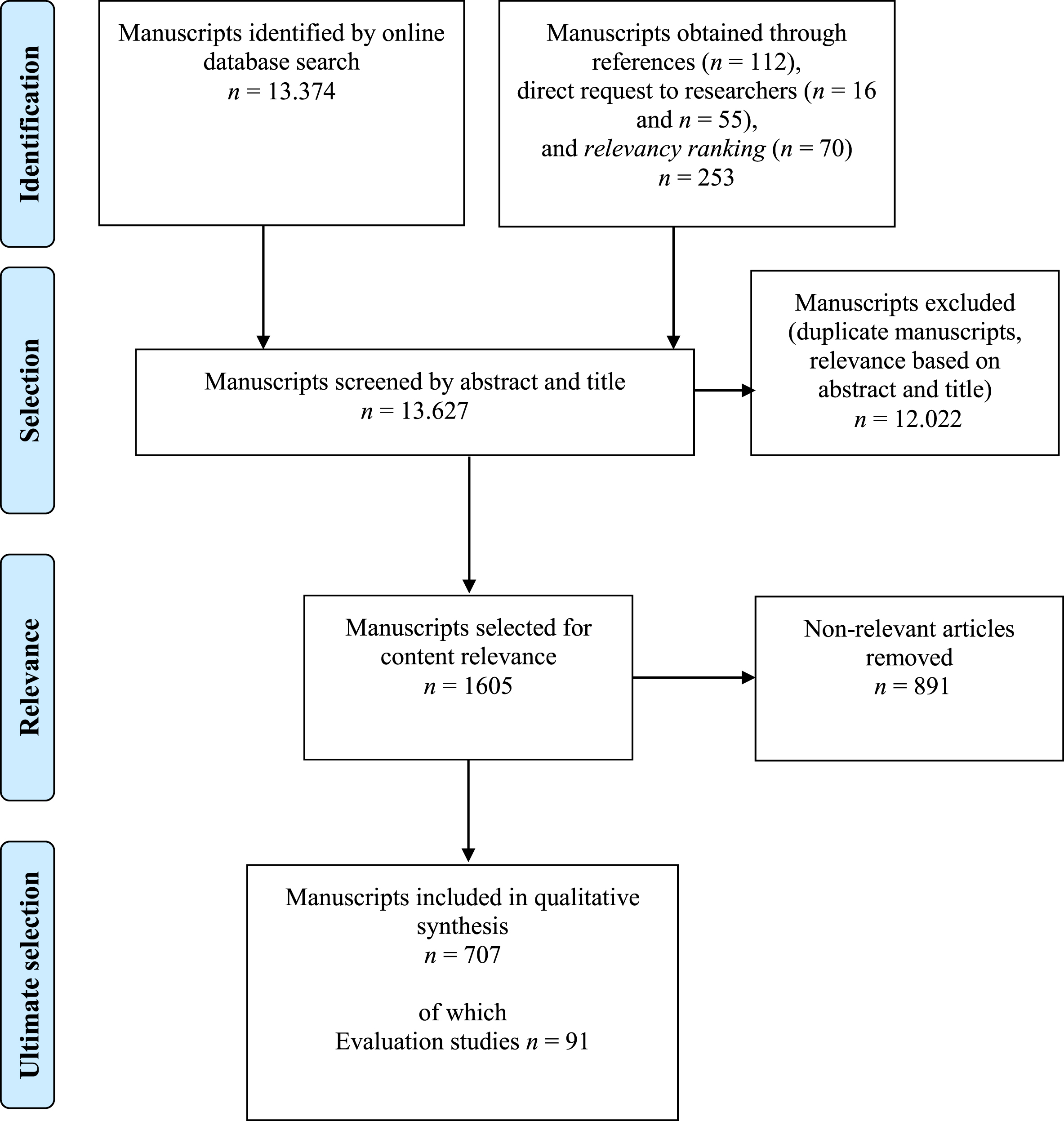

A systematic literature review was conducted focusing on empirical articles containing primary data in peer-reviewed journals. Publications in Dutch, English, and German language were included. The PRISMA procedure was followed (Moher et al., & the PRISMA Group, 2009; see Figure 2). Manuscripts were selected through a digital database search, supplemented by citation tracking in reference lists and expert consultation. A search was conducted in Google Scholar as well through which the first 200 search results were sorted by relevance.

Figure 2

PRISMA Model, Selection Procedure of Manuscripts in the Systematic Literature Review

Digital Data Sources: Two online databases were used: PsycINFO (the main database for behavioural studies) and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). The SSCI includes social science disciplines of psychology, criminology, political science and social work studies. The search was conducted on March 3, 2020.

Criteria of Inclusion and Exclusion: The inclusion criteria of literature were: peer re-viewed manuscripts including primary quantitative or qualitative empirical data describing radicalisation or deradicalisation leading to extremism. Dissertations and book chapters were not included. With regard to the methodology, for quantitative analyses we included correlational, longitudinal, timeseries, and (quasi-experimental) laboratory and field research. Studies in which existing data sources were (re-)analysed were also included. Qualitative methods included archive studies, case studies, focus group studies, interviews, participatory reseach, and analyses of video’s, text and websites.

Search Strategy: First, the search terms for the literature review were determined (see supplementary material). There were four series of search terms. The first series focused on studies on the topic of radicalisation and deradicalisation and included terms related to names of extremist groups. The second series covered methodology in order to find manuscripts with primary data. The third series focused on psychological factors related to extremism. The fourth series included terms related to intervention programs to counter radicalisation.

Citation Tracking: Citation tracking was also carried out. Reference lists of the manuscripts which were not included but were of potential interest (i.e., books) were scanned for possible additional articles containing primary data. A total of 257 manuscripts were examined for relevant references. A total of 112 manuscripts were included for further identification.

Expert Consultation: Fellow researchers, in total 55, were contacted in April 2020. The researchers hailed from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. They shared 16 studies and recommended 55 studies from peers.

Relevancy Ranking: Relevancy ranking was conducted in Google Scholar on March 9, 2020, to find cited articles published in journals without an impact factor. The search terms used for relevancy ranking are presented in the supplementary material as well. The first 200 results were examined and 70 manuscripts were selected for further screening.

De-duplication: The digital source database search resulted in a total of 13,374 manuscripts. The relevance ranking (in Google Scholar) resulted in an additional 70 studies. Duplicates were removed using the programme Zotero (https://www.zotero.org/). After de-duplication, a total of 11,397 manuscripts remained.

Selecting Manuscripts: In the first phase the authors, together with eight student research assistants, inspected the title and abstracts of 100 manuscripts for relevance. Manuscripts were identified which would be ‘included’, ‘excluded’ or ‘possibly included’. Next, the manuscripts which were categorized in the latter category were discussed. There were disagreements in assessment in 29 out of the 100 studies. The remaining titles and abstracts were divided over the research team. To get an impression of the reliability of judgments, each senior researcher judged 100 studies from each of the eight sets of student assistants. The percentage of agreement was high, ranging from 81% to 92% with an average of 84.6%. Conflicts were discussed to reach a unanimous decision for inclusion or exclusion resulting in a total of 1,605 manuscripts.

Content Relevance Screening and Qualitative Synthesis: The 1,605 studies were read and categorized by the researchers with the support of two research assistants. The articles were uploaded in the programme Mendeley (http://www.mendeley.com) and a systematic record was kept for each study in regard to the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 707 studies were included for further qualitative synthesis. The references of these 707 studies are documented in the supplementary material.

Results

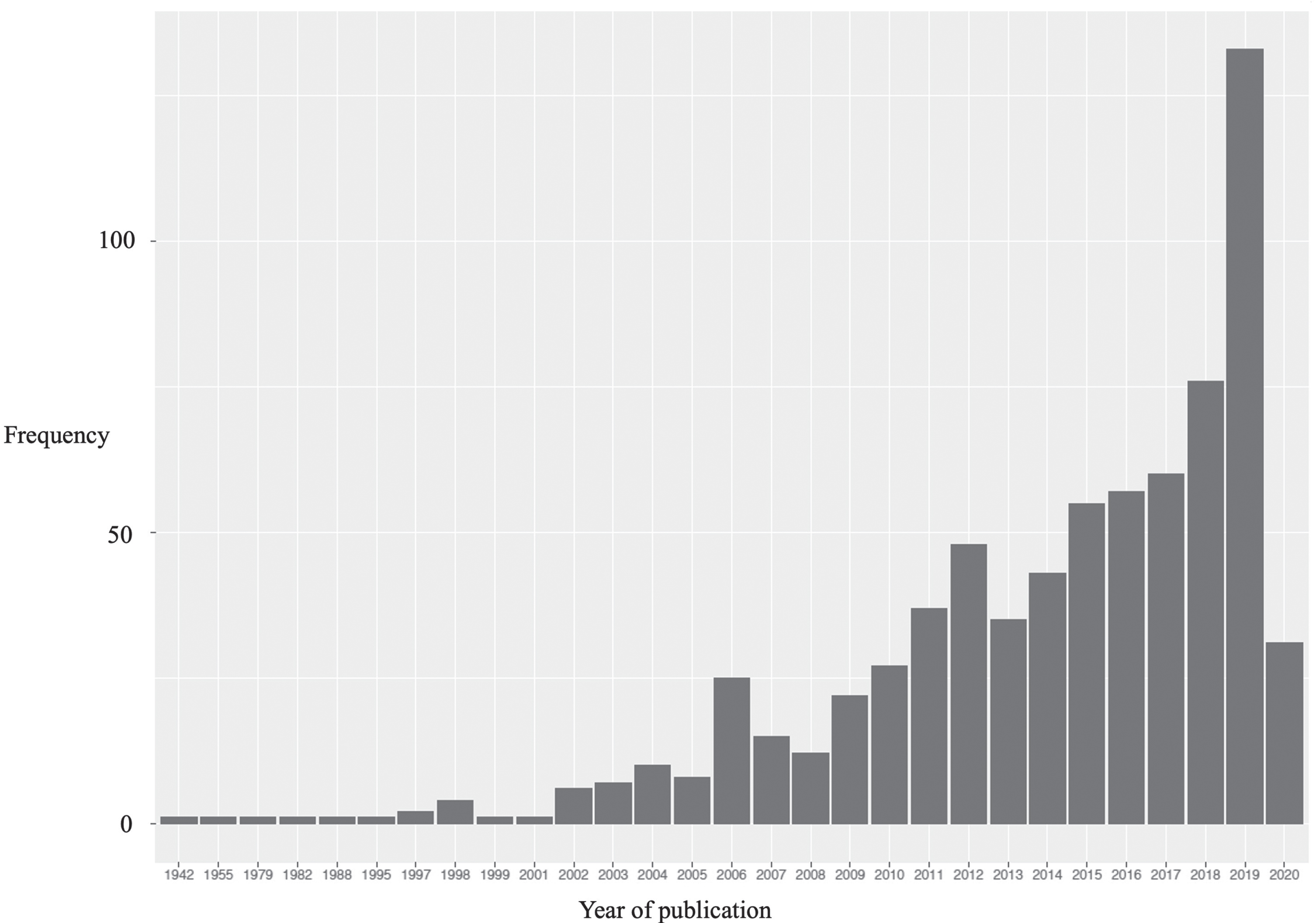

As can be seen in Figure 3, there has been a strong increase in the number of published empirical articles containing primary empirical data. In Table 1, the most frequently used quantitative and qualitative methods are given. Re-analyses of existing databases (such as the Global Terrorism Database; START, 2022), survey studies, cross-sectional and correlational study methods are most often applied. There is relatively little experimental and longitudinal work available. In regard to qualitative methods, most work involves interview studies, case studies and analyses of text, video, and archives. In the following, we discuss the different factors shown in Figure 1 which have been investigated in regard to radicalisation leading toward violent extremism.

Figure 3

Overview of the Number of Studies Published Until March 3, 2020

Table 1

Overview of the Most Frequently Used Quantitative and Qualitative Methods with the Number of Research Reports Using the Respective Method(s)

| Quantitative methods | Number of | Qualitative methods | Number of |

| research reports | research reports | ||

| Re-analysis of existing databases | 188 | Interview study | 98 |

| Survey study | 116 | Case study | 62 |

| Correlational study | 73 | Analysis of video, text, photo or webpage | 37 |

| Timeseries study | 54 | Archive study | 33 |

| Cross-sectional study | 24 | Focus group study | 10 |

| Randomized controlled trial | 13 | Participatory and ethnographic field research | 8 |

| Experimental laboratory study | 11 | ||

| Quasi-experimental study | 9 | ||

| Simulation study | 9 | ||

| Cohort study | 7 | ||

| Validation study | 7 | ||

| Longitudinal study | 6 | ||

| Field experiment | 5 |

Note. Some research reports included multiple study methods.

Demographic Factors

Of the studies that documented age, the majority (25 studies) show that violent extremists are predominantly adolescents and young adults, aged between 16 and 30 years (i.e., De Bie et al., 2015). However, in some cases older individuals are also found to be member of extremist groups, such as in the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict (Fair et al., 2017). In regard to gender, it turns out that predominantly men are receptive to extremist ideas (15 studies, i.e., Roussea et al., 2019) and that mostly males turn to violent extremism (19 studies, i.e., Meloy et al., 2015). But this does not mean that females are absent in extremist groups (Fair & Shepherd, 2006; Hanif et al., 2019; Nuraniyah, 2018).

Eleven studies show that individuals who are susceptible to extremist ideas tend to have a lower income or consider themselves relatively poor compared to their fellow citizens (i.e., Sirgy et al., 2019) and three studies report that lower income is related to extremist violence (i.e., Alkhadher & Scull, 2019b). However, three studies show the opposite pattern, pointing out that extremists have higher income (i.e., Berrebi, 2007) and six studies show no clear relationship between income and extremist actions (i.e., Schuurman et al., 2018).

Ten studies report that individuals with extremist views tend to have lower levels of education (i.e., Pedersen et al., 2018). Two studies contradict this finding and show that those with higher education levels are more likely to turn to violent extremism (Bhui et al., 2014; Kavanagh, 2011). Six studies report no link between education level and violent extremism (i.e., Mousseau, 2011).

Structural Factors

Structural factors refer to factors at the societal level. Most of the research on structural factors focused on the association with extremist violence (n = 142), whereas a lower number focused on receptiveness for extremist ideas (n = 21). A first structural (macro) factor is a lack of economic development and a low average income at the country level. The results are ambiguous: 22 studies report a negative association between poverty and extremist violence, 14 studies show a positive association and 15 studies report no association. The complexity (or relativity) is illustrated by a study of Blomberg et al. (2004) who find that a deteriorating economy results in more terroristic activities, particularly in democratic countries with relative high incomes. Furthermore, 12 studies show a positive relationship between income inequality on the country level and the number of terrorist attacks (i.e., Krieger & Meierrieks, 2019). Fourteen studies show a positive association between youth unemployment in particular on the country level and number of terrorist incidents (i.e., Gouda & Marktanner, 2019).

A more diverse picture arises in regard to education at the country level. While eight studies show a negative relationship between education level and terrorism (the lower the education level, the more terrorism; i.e., Ali & Li, 2016), three studies suggest a positive association (i.e., Weber, 2019).

Other structural factors which have been found to be clearly related to the use of extremist violence are the amount of extremist violence that is already taking place in a given country (n = 23; i.e., Frounfelker et al., 2019) and the occurrence of state repression (n = 16; i.e., Asal & Philips, 2018).

Personality Factors

In regard to personality traits (relatively stable patterns of behaviour, thoughts and emotions; McCrae & Costa, 2003), we found three studies focusing on introversion. Two studies showed a positive association between introversion and receptiveness for extremist ideology (i.e., Litman & Jimerson, 2004). Another interview study among Palestinian suicide terrorists reported no conclusive association between introversion and violent extremism (Merari et al., 2009).

Personality factors also include values. People who typically have a high Social Dominance Orientation see the world as a competitive place in which only the fittest can survive. A link between Social Dominance Orientation and susceptibility to violent extremism has been shown in several studies (i.e., Bai, 2020; Reeve, 2019). Rightwing authoritarianism, an ideology whose adherents are strongly willing to conform to authorities they see as legitimate, was shown to be associated to radical right-wing extremist ideology (i.e., Canetti & Pedahzur, 2002; Faragó et al., 2019). Religious beliefs are also inextricably tied to the values that a person possesses. A few studies show that religiousity is related to greater support for extremist ideology (Araj, 2012; Beller & Kröger, 2018).

Besides values, basic needs have been shown as predictors of radicalisation to violent extremism. First, a higher need for significance was the focus in 26 studies and has been associated with more support for extremist ideology (i.e., Kruglanski et al., 2009; Troian et al., 2019). Seventeen studies found an association between a higher need for justice and receptiveness for extremist ideology (i.e., Nilsson, 2019). Other needs which have been found to be associated with violent extremism is the need for sensation and adventure (Schumpe et al., 2018) and the need for identity (Bérubé et al., 2019).

Nineteen studies focused on mental health as personality factor in relation to radicalisation. Bhui et al. (2014) found that depressive symptoms were associated with extremist violence, but other studies showed no association (Brym & Araj, 2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder has been associated with extremist violence (i.e., Ellis et al., 2015; Rolling & Corduan, 2018). Behavioural problems have also been found to be related to extremist violent behaviour (i.e., Pedersen et al., 2018; Rolling & Corduan, 2018; Simi et al., 2016).

Group Factors

As various studies show, many members of radical groups connect to that group through family, friends or acquaintances. In the sensitivity and group phase, an individual’s own social environment can provide information about the radical group and its ideology and can therefore be a precursor for joining an extremist group. This can occur both offline and online (Bastug et al., 2018). The group also plays an important role in the action phase. Most terrorist attacks are carried out in groups (Spaaij, 2010). The appreciation an individual receives from the group has also been shown to be an important factor which can drive an individual to radicalise further. This appreciation can be in terms of the tasks the individual performs, but also the feeling of belonging to a greater whole through this group membership (“from zero to hero”). In this way, the group can fulfil the “quest for significance” (Webber et al., 2018), meeting the earlier need for significance, but also a need for a positive identity.

Another important group factor is us-versus-them thinking. Extremist groups are often tight-knit and members feel a distance to those outside of the group, as this statement by a former member of a far-right group in Germany illustrates: “The aim of the extreme-right scene is to form a popular community, and it is relatively closed. We see ourselves as a scene, as a body, we feel connected” (Baugut & Neumann, 2019, p. 705). An important group factor related to extremist ideology concerns perceived group threat (Doosje et al., 2012, 2013). Perceived group threat goes a step further than us-against-them thinking. There is the notion that other groups threaten the current status of the own group according to members of the extremist group. Such perceived group threat may cause people to become (even) more supportive of their group in the sensitivity and group phase (Riek et al., 2006). Perceived threat has also been related to engagement in violent extremist behaviours (Beller & Kröger, 2018).

Relative deprivation refers to a ‘deficit relative to something’. People may experience a deficit in different areas (e.g., economic, or social). They can conclude this from comparisons such as comparisons with other groups, or compared to one own standard of living in the past. Experiencing more so-called relative deprivation has been associated with greater susceptibility to violent extremism (Decker et al., 2013; Doosje et al., 2012, 2013). Other group-related factors related to violent extremism include high group cohesion (Mullen & Copper, 1994; Price, 2012), a strong group ideology (Cook & Lounsbery, 2011; Ferguson & McAuley, 2020), and group size (i.e., large groups commit more attacks than small groups; Cook & Lounsbery, 2011).

Trigger Factors

Trigger factors are concrete events which are the cause of further radicalisation - functioning as catalysts - or which reverse the process - and thereby function as turning points (Feddes et al., 2016, 2020). Trigger factors can be found at the micro-, meso-, and macro-level. At a micro-level, stress triggering events have been found to be related to violent extremism (Gill et al., 2014; Böckler et al., 2018). These events include experiences of discrimination and events related to social exclusion, negative events in the family context (Rink & Sharma, 2018; Kortam, 2017; Klausen et al., 2016), losing a job or dropping out of education can also serve as a catalyst, which have been argued to increase susceptibility to violent extremism (Corner et al., 2019; Gill et al., 2019; Rink & Sharma, 2018). Jasko et al. (2017) call the loss of a job, or failure to complete an education, a major achievement failure which is related to violent extremism.

A confrontation with death has been associated with increased receptivity to extremist ideology in several studies (i.e., Speckhard & Ahkmedova, 2006; Gill et al., 2014; Nilsson, 2019). Experimental research among non-radical participants, however, yields mixed findings related to the terror management hypothesis. This hypothesis is derived from Terror Management Theory and states that a confrontation with death (mortality salience) leads to increasing support for ideology-based violence. For example, whereas Pyszczynski et al. (2006) found evidence for this hypothesis in two experimental studies (with students in Iran and with students in the United States), Vergani et al. (2019) did not find this effect.

Experiencing (extreme) violence is considered to be an important trigger factor (Knight et al., 2017; Isaacs, 2016) as are negative experiences with authorities (Winter & Muhanna-Matar, 2020; Soibelman, 2004) and encountering a recruiter (Ilardi, 2013).

The participation in an extremist group’s training can act as a catalyst in the transition to the action phase of radicalisation as it may increase the individual’s willingness to use violence. For example, performing a dry run (a simulation of a planned attack) is considered an important factor that preludes the actual attack (Gill et al., 2014). A farewell message has also been associated with the move towards the use of ideology-based violence (Nesser, 2006).

Finally, at a macro-level, events at the local, national or global level that lead to a sense of disregard or perceived threat to one’s own group have been assocated with greater willingness to use violence (Simi et al., 2017; Hwang & Schulze, 2018).

Capacity and Opportunity Factors

Capacity factors refer to the question whether someone is capable of extremist behaviour. Learning through imitation is considered to be a capacity factor (Knight et al., 2017; Mullins & Young, 2012). Sometimes it relates to role models such as family members or friends (Pfundmair et al., 2019). At a macro-level, it appears that more attacks take place in countries with higher levels of violence, which could possibly indicate desensitisation through exposure (in addition to imitation - Mullins & Young, 2012). Another capacity factor is dehumanisation of targets, which results in a reduced empathy making it easier for people to commit violence (Pfundmair et al., 2019). An ideology that prescribes violence is also mentioned as an important capacity factor (Böckler et al., 2015). Research among far-right extremists in Finland (Ekman, 2018) and in Germany (Baugut & Neumann, 2019) has shown that social media can play an important role in spreading this ideology. People also need to be physically prepared for violence which often happens through training and instruction (Knight et al., 2017). Other factors include obtaining funding and weapons (Novikov & Koshkin, 2019).

Besides capacity, opportunity factors have also been considered in the literature. Opportunity factors refer to the question what can encourage extremist behaviour. For example, the presence of attractive targets (which are attractive because of their status or symbolic value) is related to violent extremism (Clarke & Newman, 2006). But also proximity to the target matters, such that successful attacks take place closer to where terrorists live than unsuccessful attacks (Klein et al., 2017). At a macro-level, an unstable political state is also an opportunity factor as was earlier discussed in relation to the structural factors. Relatively many attacks take place in politically unstable countries (Fahey & Lafree, 2015). Finally, a negative relationship is found between the presence and strength of security agencies and violent extremism (e.g., Bejan & Parkin, 2015; Klein et al., 2017). So the greater the security measures, the smaller the number of terrorist attacks.

Resilience Factors

Resilience answers questions such as “Why is one person susceptible to violent extremism but not another?” and “Why does one person turn to violence but not the other?”. A distinction is made between cognitive, affective and behavioural resilience. An example of a cognitive resilience factor is more knowledge of democracy, which was associated with lower levels of support for violent extremism (Feddes et al., 2019). Critical thinking refers to being open to diverse perspectives (Ali et al., 2017). Many counter terrorism, extremism and radicalisation (CTER) interventions focus on this factor. The empirical evidence suggests it is effective in lowering susceptibility to violent extremism (Aiello et al., 2018; Spalek & Davies, 2012). Being able to self-reflect is also considered to be an important cognitive resilience factor. It can be taught, for example, by writing one’s own life story to gain insight into one’s own past (Gielen, 2018). Religion can also serve as a cognitive resilience factor according to Rousseau and colleagues (2019). In an online survey of nearly 1,900 Canadian students, they found that students who reported negative life experiences showed more sympathy for violent extremism. This effect was moderated by religious belief. Religious students supported radical violence less than non-religious students. Another cognitive resilience factor is wanting to avoid negative consequences. A greater motivation to do so was found to be related to lower support for violent extremism (Ilardi, 2013).

Emotional resilience factors such as emotion regulation also emerge from the literature. People who can cope well with negative emotions arising from setbacks are less susceptible to violent extremism (Rousseau et al., 2019). Also, intervention studies aimed at emotion regulation skills reported increased emotional resilience (Muluk et al., 2020). Having self-confidence and empathy are other emotional resilience factors related to a lower susceptibility to violent extremism (Feddes et al., 2015; Knight et al., 2017; Van Brunt et al., 2017). However, Dechesne (2012) found that having high self-esteem was actually related to more violent extremism. Other emotional resilience factors are feeling accepted (Murphy et al., 2019) and feeling safe (Van Brunt et al., 2017), as well as having trust in the government (Shanaah, 2019; Doosje et al., 2012, 2013). Feelings of regret, guilt, shame, and disappointment regarding past violent extremist behaviour are associated with lowered support for violent extremsim (Bérube et al., 2019; Simi et al., 2017).

Finally, being able to maintain a social network outside the extremist group is mentioned as a behavioural resilience factor in several studies (Altier et al., 2017; Bérubé et al., 2019; Gielen, 2018).

Discussion

This review shows that a rich variety of methods are being used to study processes of radicalisation and violent extremism. The existing empirical work mainly consists of correlational and cross-sectional work. Relatively little experimental and longitudinal work exists which is in line with the recent systematic reviews conducted by Jahnke et al. (2022) and Lösel et al. (2018). The majority of quantitative studies involve a re-analysis of existing data-bases such as the Global Terrorism Database (START, 2022). The present research also shows that a rich diversity of qualitative research methods is used (interview studies, case studies, investigation of video, online material, and archives) which complements the quantitative work and is an important source of hypothesis generation in earlier stages of research.

Under what conditions are individuals receptive to extremist ideas and groups? Or, in terms of our model of radicalisation, what factors are associated with the sensitivity and (early) group phase? If we interpret the term ‘conditions’ broadly, at the macro-level, some studies point to conditions such as polarisation, repression and experiences with discrimination. Demographic factors include being young, male, religious, low educated and having low income. On the micro (individual) level values such as social dominance orientation, ingroup superiority and (right-wing) authoritarianism emerge, as do personality traits such as introversion. Mental health such as (symptoms of) depression, PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), personality disorders, and traits such as insecure attachment and low empathy are linked with receptivity.

Basic (strongly felt) needs are also frequently associated with receptivity to radical ideas, including a need for significance, identity and/or justice. The importance of the need for significance is also highlighted by Kruglanski and colleagues as a central motivational factor of radicalisation (Kruglanski et al., 2019). In line with the latter two variables, Jahnke et al. (2022) found that stronger identification and higher perceptions of group deprivation (injustice done to the own group) are risk factors of political violence. For the satisfaction of these needs, a person may turn to an extremist group. At this point, various group factors - i.e., conditions at the meso/group level - come into play. For example, a social environment with radical people (in the family or group of friends) can fuel a person’s receptivity to extremist ideas or groups.

In many cases, these factors –needs, mental health, but also one’s (level of) education or labor market position –are inextricabily tied with (or caused by) the concrete events we called trigger factors. Indeed, the social-developmental model of radicalization (Beelmann, 2020) identifies “trigger conditions” or “trigger accelerators” as a key proximal factor in the radicalisation process. In line with this, Feddes et al. (2016, 2020) make a distinction between trigger factors that serve as a catalyst (the cause of further radicalisation) or as a turning point (initiating or reversing the process). From the literature, we identified a range of trigger factors, such as concrete experiences with extreme forms of discrimination and exclusion, (marital) divorces and quarrels in the family, confrontation with death (of a loved one) and the loss of a job or termination of an education, in particular, can make someone susceptible to extremism. This aligns with Beelmann (2020) who proposed that individual crises of contexts within a broader context can lead to identity problems, feeling prejudiced against, development of antisocial attitudes and behaviour, and fuel political and religious ideologies.

Additional research is needed to determine under what conditions a trigger factor is a catalyst or a turning point in the radicalisation process. For example, experiences of discrimination and social exclusion in an intergroup context can increase feelings of humiliation, shame and insecurity. These experiences, in turn, lead to a greater need for closure, which was found to be positively related to greater support for violent extremism. In that respect, these incidents can be considered to be a catalyst in the radicalisation process leading to violent extremism.

In regard to our second research question - when do people turn to actual violence and other extremist acts? - the findings regarding demographic factors showed that people who turn to (violent) action are more often young and male, but we see high diversity in terms of education level and income. Important structural factors are the number of young residents, and contexts of political instability, repression, polarisation, high unemployment rates and great income disparities.

Looking at personality factors, compared to the first research question, we see a more limited number of factors that seem to be associated with the move to violence. These include, for example, the specific value of ingroup superiority (people who see their own group as superior are more likely to resort to extremist violence). In terms of basic needs, the need for sensation and adventure stands out as well as the need for significance. In mental health, we see that, in addition to being linked to mental problems in general, that research also specifically points to a link between extremist violence and PTSD.

Almost all terrorist violence takes place in some kind of group context, and it is therefore not surprising that many of the group factors we found are particularly relevant to research question 2. Thus, the group one belongs to and identifies with is particularly important in the radicalisation process (Doosje et al., in press). A group narrative of strong us-them thinking can make one feel superior as a group, but a threatened superiority has been associated with ideology-based violence.

Our review suggests that the size of the extremist group is also related to committing violence - large groups are relatively likely to commit extremist violence, while the relation with ideology is less clear. And in terms of capacity, we see that it is mainly from within the group that a person is prepared - both mentally and physically - to turn to violence. Finally, the trigger factors associated with violence are also often group-related. These may include, for example, an event at the local, national or global level that leads to a sense of disregard and threat, participation in a training exercise - obviously facilitated by the group - and targeted attacks on leaders of the extremist group in question. In addition, previous (own) experiences of violence are also linked to committing violence, as well as specific ‘points of no return’ such as writing a farewell letter or a will.

Which factors can make someone resilient to radical influences? First, we have identified that this includes cognitive factors such as critical thinking and having relevant knowledge and a stable identity. This aligns with Lösel et al. (2018) who identify education, knowledge of and abiding to democratic values as well as law abidance as protective factors. Secondly, our analysis shows that emotional factors such as being able to express and deal with negative emotions well, having self-confidence and good empathic skills, and feeling accepted and safe in a society also make people more resilient. These findings align with the meta-analytic results of Jahnke (2022). Finally, behavioural factors such as maintaining a diverse social network also contribute to reduced susceptibility to extremism. Having a diverse social network creates greater resilience against joining an extremist group, and it makes it easier to leave an extremist group.

In terms of resilience, there is much less evidence about the step to extremist violence; usually, by that time, in the action phase, this resilience has long since dissipated. The only resilience factor with an unequivocal link in this context is that of moral rules: the rules people have formulated for themselves about what behaviour is right or wrong can form an ‘internal brake’ against extremist violence. A factor like self-esteem is much more difficult to interpret here; on the one hand, low or damaged self-esteem may be related to taking greater risks such as committing violence, but on the other hand, an ‘inflated’ form of self-esteem (narcissism) is also associated with a greater willingness to commit violence.

Finally, even if all internal resistances and obstacles have been removed, and the motivation is crystal clear, there are always the opportunity factors that can stand between the extremist and the perpetration of violence. As described, these include, for example, the availability of attractive and nearby targets, as well as the presence or absence of police and security forces.

A limitation of the present study is that we cannot draw strong conclusions about the relative importance of all factors in regard to susceptibility to extremist ideology and engagement in extremist violence. Methodological differences, as well as differences in social contexts (i.e., studies conducted in areas characterized by high level of conflict are different from those in low level of conflict) could serve as third variables explaining effects. Also, in our review we did not distinguish between different developmental stages and importance of group factors. As argued by Beelmann (2020), different factors may play a different role at different age ranges (i.e., early childhood, adolescence, young adulthood). This ontological approach could help understanding the relative importance of factors, and thereby also provide a valuable avenue for identifying which factors to focus on in counter-radicalisation interventions.

To conclude, radicalisation is a complex and dynamic process, in which a wide range of factors can play a role. In the present research we provided a model in which the different factors were summarised and related to three different phases of radicalisation. There are several reasons why the question of the cause of radicalisation to extremism is difficult to answer, even using this extensive research. First, the studies in our review mostly concerned correlational results. In other words, factors were associated with susceptibility to extremist ideology or with violence, but for which it is not clear whether they actually have a causal influence. Qualitative studies with concrete descriptions of individual radicalisation processes are valuable as these studies complement the correlational studies showing that it is always a combination of factors. There is no single factor that is (always) decisive in the (de)radicalisation process. There are always different possible combinations of factors at different levels (micro-, meso- and macro-level) in combination with structural conditions and incidental trigger events. Future research should focus on identifying which particular combination can explain further (de)radicalisation in the sensitivity, group, and action phase.

Supplementary Material

[1] The supplementary material (the search terms and the index of references of studies included in the literature review) is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/DEV-230345.

References

1 | All references included in the review are listed in the supplementary material. |

2 | Beelmann, A. ((2020) ). Asocial-developmental model of radicalization:Asystematic integration of existing theories and empirical research, International Journal of Conflict and Violence 14: (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-3778 |

3 | Doosje, B. , Moghaddam, F. M. , Kruglanski, A. W. , De Wolf, A. , Mann, L. , Feddes, A. R. ((2016) ). Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11: , 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.008 |

4 | Doosje, B. , Feddes, A.R. , Mann, L. (In press). It’s the group, not just the individual: Social identity and its link to exclusion and extremism. In Pfundmair, M., Hales A.,&Williams, K. D. Exclusion and extremism: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press. |

5 | Emmelkamp, J. , Asscher, J. J. , Wissink, I. B. , Stams, G. J. J. M. (2020). Risk factors for (violent) radicalization in juveniles: A multilevel meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101489 |

6 | Feddes, A. R. , Mann, L. , Nickolson, L. , Doosje, B. (2020). Psychological perspectives on radicalization. Routledge. |

7 | Feddes, A. R. , Nickolson, L. , Doosje, B. ((2016) ). Trigger factoren in het radicaliseringsproces [Trigger factors in the radicalisation process]. Justitiele Verkenningen, 2: , 22–48. https://doi.org/10.5553/JV/016758502016042002003 |

8 | Horgan, J. ((2008) ). From profiles to pathways and roots to routes: Perspectives from psychology on radicalization into terrorism, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618: (1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716208317539 |

9 | Horgan, J. G. ((2017) ). Psychology of terrorism: Introduction to the special issue, American Psychologist 72: (3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.07.008https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000148 |

10 | Kruglanski, A. W. , Bélanger, J. J. , Gunaratna R. (2019). The three pillars of radicalization. Needs, narratives, and networks. Oxford University Press. |

11 | Institute for Economics and Peace (2019). Global terrorism index 2019: Measuring the impact of terrorism. Vision of Humanity. Retrieved from: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/11/GTI-2019-web.pdf |

12 | Jahnke, S. , Abad Borger, K. , Beelmann, A. ((2022) ). Predictors of political violence outcomes among young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Political Psychology 43: (1), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12743. |

13 | King, M. , Taylor, D. M. ((2011) ). The radicalization of home grown Jihadists.Areviewof theoretical models and social psychological evidence, Terrorism and Political Violence 23: (4), 602–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2011.587064 |

14 | Lösel, F. , King, S. , Bender, D. , Jugl, I. ((2018) ). Protective factors against extremism and violent radicalization:Asystematic review of research. International Journal of Developmental Science, 12: (1–2), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-1702418 |

15 | McCrae, R. R. , Costa, P.T. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. Guilford Press. |

16 | Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. ((2009) ). PRISMA Group: Methods of systematic reviews and meta-analysis - preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement, Journal Clinical Epidemiology 62: , 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 |

17 | Riek, B. M. , Mania, E. W. , Gaertner, S. L. ((2006) ). Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review, Personality and Social Psychology Review 10: (4), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4 |

18 | Schmid, A. P. (2013). Radicalisation, de-radicalisation, counter radicalisation: A conceptual discussion and literature review. www.icct.nl. |

19 | Schuurman, B. W. ((2019) ). Topics in terrorism research: Reviewing trends and gaps, 2007-2016, Critical Studies on Terrorism 12: (3), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2019.1579777 |

20 | Schuurman, B. W. , Bakker, E. , Eijkman, Q. (2018). Structural influences on involvement in European homegrown jihadism: A case study. Terrorism and Political Violence, 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2016.1158165 |

21 | START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism). (2022). Global Terrorism Database 1970 - 2020 [data file]. https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd |

22 | Vergani, M. , Iqbal, M. , Ilbahar, E. , Barton, G. ((2020) ). The three Ps of radicalization: Push, pull and personal. A systematic scoping review of the scientific evidence about radicalization into violent extremism. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 43: (10), 854. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1505686 |

23 | Wolfowicz, M. , Litmanovitz, Y. , Weisburd, D. , Hasisi, B. ((2020) ). A field-wide systematic review and meta-analysis of putative risk and protective factors for fadicalization outcomes, Journal of Quantitative Criminology 36: (3), 407–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09439-4 |

Bio Sketches

Allard R. Feddes, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Social Psychology at the Department of Social Psychology of the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. His research focuses on how group membership influences (development of) our thinking (cognition), affect (emotions), and behaviour. He is also interested in the assessment of effectiveness of interventions.

Lars Nickolson, MSc., is PhD-candidate at the department of Political Science of the University of Amsterdam. For more than a decade, he has been involved with counter-radicalisation policy both as a researcher and an advisor, working within and outside of the Dutch government.

Naomi van Bergen, MSC., is a PhD-student in Educational Sciences at the Behavioral Science Institute, Radboud University Nijmegen. Her research focuses on digital reading skills of school children.

Liesbeth Mann, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests are varied and cover topics in the area of (cross-) cultural psychology such as migration and acculturation, intergroup relations, self and identity, political psychology (e.g., radicalisation, genocide and the aftermath of mass conflict and crime) and emotions.

Bertjan Doosje, PhD, is an Associate Professor (previously Full Professor on Radicalisation) at the University of Amsterdam. He has examined and written about attitudes, emotions and behaviour in intergroup relations, including stereotyping, prejudice, discrimination, group-based guilt and collective action. He is also interested in the role of cultural background in shaping processes between romantic partners.