Collaborative competences for agile public servants: A case study on public sector innovation fellowships

Abstract

In times of crisis and with the increase of new ways of working, public sector organisations increasingly include agile practices in their working practices. To successfully transform public sector organisations into agile organisations, public servants require a new set of competences. Informal learning is a key element that helps public servants to build and apply these competences, e.g., through the collaboration with external experts in public sector innovation fellowships. To observe how collaborative competences for agile public organisations can be developed successfully by involving external experts, I conducted a case study on two iterations of a public sector innovation fellowship. My findings show that throughout the fellowships, competences are being developed in a collaborative process on a personal and organisational level. The practical application of the learned methods, personal reflection, and the development of organisational networks transform the collaborative into a learning process, allowing public servants to develop new competences and bring them into their organisation.

1.Introduction

The public sector needs to provide steady structures in politically changing environments and times of crisis (Van der Wal, 2020). Public organisations are dealing with internal challenges, such as demographic change, but are also asked to find short-term, viable, and sustainable solutions to wicked problems (Hofstad & Torfing, 2015; Peters et al., 2011), such as climate change or epidemics. These challenges require agile and proactive organisations (Mills & Keremah, 2020) with personnel who can find innovative solutions to these problems. To achieve this, actors in the public sector need to work together, break down communicational walls, and create these solutions through collaboration. This study examines how public servants can develop the necessary competences for adopting and applying agile practices through the collaboration with external experts in public sector innovation fellowships.

Implementing agile methods in the day-to-day work of a public organisation can contribute to a public service that is able to react to problems and design innovative solutions. The development of collaborative competences helps public servants to work together and apply agile practices to better manage crises (Raut et al., 2022) or react to other developments, e.g., changes in the ways of working. Mergel, Ganapati, and Whitford (2021) state that “agile administrations are open to reforms, adaptation to the changing environment, public values, and public needs” (p. 163).

With its origins in software development (Tripp et al., 2016), agility has become far broader than encompassing specific technical issues (Neumann & Fischer, 2023). The term not only embodies changed working styles and methods, but also the transformation of an organisation’s culture. Neumann et al. (2024) describe agile government as “a form of governance innovation consisting of organization-specific mixes of cultural, structural, and procedural adaptations geared towards making public organizations more flexible in changing environments, ultimately pursuing the goal of increasing efficiency, effectiveness, and user satisfaction” (pp. 235–252).

In the context of this article, I will use the terms agile, agility, and mainly agile practices to refer to the implementation of agile working styles and methods within a public sector organisation. In more specific contexts, I will refer to methods that are used in this context as agile methods. Agile organisations are able to develop solutions and solve complex problems (Mergel, Ganapati, et al., 2021), by applying agile practices (Neumann & Fischer, 2023). An agile public sector is a public sector with fewer hierarchical and bureaucratic barriers, with public servants who are able to collaborate and find innovative solutions to the issues they are facing. The development of collaborative competences can support public servants in gaining trust in and understanding for agile practices and changed organisational structures.

Collaboration with external experts who are already experienced with agile methods and organisations can foster the informal learning processes to develop these competences. So far, the academic literature mainly focuses on this competence development through formal trainings and education (Skule, 2004) or digital skills (Vuorikari et al., 2022). New, informal ways of learning can include more applied approaches, for example public sector innovation fellowships in which public servants collaborate with external experts. Elsen et al. (2022) discuss social informal learning, but with a focus on intraorganisational collaboration with colleagues, not external experts. This study addresses this gap by examining the process of acquiring collaborative competences through an informal learning process with the goal of improving the adoption and application of agile practices within public organisations.

To explore the development of these competences through public sector innovation fellowships, I conducted a case study in the public sector following an embedded single case study design (Yin, 2018). Through interviews and observations, I examine how the collaboration between public servants and internal experts bridges the gap between individual collaborative competences, the process of developing them in informal learning environments with its drivers and barriers, and the effects this has on the application of agile practices in public sector organisations. The findings of this study show that the practical application of the learnings, personal reflection, and the formation of organisational networks were key factors in initiating a learning process. Communication, organisational culture, the availability of resources and hierarchical support can be drivers or barriers for informal learning. This study also contributes to the literature on public sector innovation, especially around agility, by providing unique empirical insights from a central governmental level and a focus on the process of informal learning with external experts. To further explore the research gap and theoretical foundation of this study, the next section delves into the theoretical background, before I present the methodology, findings, and discussion.

2.Theoretical background

In this study I argue that informal learning processes benefit the adoption of agile practices in the public sector by contributing to the development of collaborative competences. These competences provide the basis for public servants to effectively work together, actively apply agile practices and create innovative solutions across organisational boundaries. To provide the theoretical background for these claims and build a basis for the development of my research questions, first, I discuss the need for and definition of collaborative competences for agile public servants. Second, I examine how these collaborative competences can be informally developed, with a particular focus on collaborating with external experts in innovation fellowships. Third and last, drawing from existing literature, I outline the potential impacts of competence development in innovation fellowships on the adoption of agile practices in public organisations.

2.1The need for collaborative competences for agile public servants

The public sector faces many challenges that create the need for openness and reforms. The adoption of agile practices is a key component in paving the way for these changes (Mergel, Ganapati, et al., 2021). With an increased focus on providing more innovative services and improving internal processes, agile practices have become a necessity for the public sector in recent years (see, e.g., Ribeiro & Domingues, 2018). However, the changes that go along with this development often meet resistance by members of public sector organisations (Malik et al., 2021; Moussa et al., 2018). The cross-functional collaboration and the development of competences that are necessary to adopt and apply agile practices can be hindered by rigid bureaucratical and hierarchical structures and traditions, as, e.g., Mergel (2023) suggests.

One factor that stands out in the discussion about agile public servants and proves especially difficult for the public sector, is the need for cross-functional collaboration and open communication (see Mergel, 2023). An agile public service requires new competences to implement these changes (Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2020). Successful collaboration in agile organisations requires competences that go beyond mere technical skills. Chinn et al. (2020) mention agile working as a subcategory of future skills for the public sector, while Mergel et al. (2021) define personal and subject-specific competences for agile public servants. A key aspect of these agile competences is their close connection to the ability to collaborate within the public sector. While some authors like Chinn et al. (2020) or Mergel et al. (2021) refer specifically to agile competences, in my research I highlight the connection between agile practices and the necessary competences and will focus on the broader category of collaborative competences.

For the public sector, Getha-Taylor (2008) breaks collaborative competences down into interpersonal understanding, teamwork and cooperation, and team leadership. Zakrzewska et al. (2020) also focus on competences that involve people, including, among others, self-reflection, communication, relationships and engagement, as well as leadership and teamwork, with the aim of contributing to innovation. For an educational context, Sanojca and Eneau (2016) define collaborative competences for different levels of collaboration, partly based on Morse and Stephens (2012), who allocate competences to different themes, but also highlight a collaborative mindset and openness as meta-competences. Based on these frameworks, self-reflection, teamwork, and openness for innovation are core elements of the competences public servants need. As these competences concern the roles and relationships within the public sector (Suter et al., 2009), their development needs to be built on reflection and interaction.

2.2Informal learning of collaborative competences in public sector innovation fellowships

Both quantitative and qualitative studies have shown that informal learning plays a significant role in developing competences in the workplace (Cunningham & Hillier, 2013; Elsen et al., 2022). Ipe (2003) highlights, that informal knowledge sharing is a significant part of personal development within organisations. Elsen et al. (2022) explain how social informal learning can foster competence development in the public sector. Since informal learning processes do usually not contain fixed learning outcomes and their evaluation, self-reflection is a significant part in sustaining the competences developed throughout the processes. In accordance to Schön (1987), this reflection is more closely related to individual competence development and rational thinking than to any specific discipline (Neumann Jr, 1999). Interactions and learning by doing have the potential to build competences that are relevant for public servants’ daily working life (Jeon & Kim, 2012).

So far, this interaction- and reflection-based development of competences is usually examined in the context of informal learning within the organisation, and is often even thought of as incidental (le Clus, 2011). Agile practices add a new dimension to this discussion, by inviting a deliberate outside perspective into a team. Stemming from software development, agile teams usually imply the involvement of external experts or specialists (Md. Rejab et al., 2015), creating a diverse environment to learn from one another. This is new for the public sector, where the literature so far mainly focuses on learning from service users in co-creation or co-production processes (Bancerz, 2021; Koivisto et al., 2015; Nardelli et al., 2015). External experts are thus often involved in public sector activities in their role as participating users or, as e.g. von Helden et al. (2012) observe, as consultants. Inviting external experts as participants in informal learning processes could provide new perspectives.

Fellowships can be a key format to open the door for such exchanges. In this format it becomes possible to bring external experts into a dedicated project. A growing interest in the role of interprofessional competences in medical research (see, e.g., Smith et al., 2022), for example, has led to research into how innovation fellowships might support the development of these competences, emphasising the connection between knowledge and its practical application (Prado et al., 2018).

So far, many programmes, such as the CoGenerate Innovation Fellowship (Halvorsen et al., 2023) or some Health Innovation Fellowships (Prado et al., 2018) focus on building successful leaders for innovative organisations. Others highlight students as the next generation of creative leaders (Whitney, 2018). Fellows in these programmes can be people from diverse backgrounds and demographic characteristics with a general interest in the respective field (see, e.g., Halvorsen et al., 2023) or professionals who want to further develop their competences (see, e.g., Prado et al., 2018). Fellowship programmes allow participants to connect learnings to organisational needs and practices (Cunningham & Hillier, 2013), while still acknowledging people as the agents of organisational learning. Both the individual and organisational learning processes take time. Fellowships may happen in iterations over two (Whitney, 2018) to three years (Prado et al., 2018) and the real effects might only become visible after 18 months or more (Smith et al., 2022). To truly make the effects of and the informal learning process within these fellowships visible, the public sector requires strategies to account for the long-term effects of inviting external experts into teams and organisations.

2.3Effects of informal learning on the adoption of agile practices in public organisations

Collaborative competences, agile routines, and the involvement of external experts have an impact on the organisational culture of the public sector, an aspect that is still not fully explored in the literature (Vries et al., 2016). Organisational culture and organisational structures in the bureaucratic public sector are often defined as barriers to, and not objects of, projects like public sector innovation fellowships (Cinar et al., 2019; Sørensen & Torfing, 2011; Zasa et al., 2020). Bommert (2010) presents these structures as barriers to be overcome by collaboration. Implementing informal learning processes into these structures may be a challenge, but can have a positive impact on organisational learning as prior literature has shown a complex connection between these processes (Antonacopoulou, 2006) Organisations are heavily influenced by how their members lead, work, and collaborate. That is why initiating learning within organisations and integrating new methods, such as agile practices, has been found to have an impact on job satisfaction, teamwork and management practices (Tripp et al., 2016). Al Saifi (2015) has focused the discussion of organisational culture on the intersection of knowledge creation, sharing, and application. Bringing informal individual and organisational learning together in innovation fellowships includes practical, reflective, and collaborative aspects, mirroring the elements of collaborative competences

While the literature shows these elements, studies tend to focus the categorisation and classification of collaborative competences (Chinn et al., 2020; Getha-Taylor, 2008; Getha-Taylor et al., 2016; Mergel, Brahimi, et al., 2021; Zakrzewska et al., 2020), leaving open how public servants may actually develop them. Aside from Getha-Taylor (2008) many of these studies do not target the public sector. While Morse and Stephens (2012) as well as Sanojca and Eneau (2016) focus on education, other authors (see, e.g., Zakrzewska et al., 2020) highlight the development of competences to enhance innovation in the private sector. Studies that have been looking at agile practices in the public sector so far have mainly examined the implementation of agile methodologies (see, e.g., Ribeiro & Domingues, 2018), not how their prerequisite competences can be developed through informal learning practices. This study can contribute to literature on public sector innovation by highlighting the process of informal learning to develop the competences that are needed for an agile public sector. To address this gap, I ask the following questions:

(RQ1) How can public servants acquire collaborative competences that support agile practices in public organisations? (RQ2) Which drivers and barriers influence successful informal learning in public sector innovation fellowships? (RQ3) How does informal learning in public sector innovation fellowships contribute to the adoption and application of agile practices?

In the subsequent sections, I will answer these questions with insights from a case study, which provides practical perspectives on the informal learning of collaborative competences in the context of public sector innovation fellowships and the adoption of agile practices in public sector organisations.

3.Research design

To explore how public servants can develop competences by collaborating with external experts and how this affects the team and organisation they are working in, I shadowed a public administration in a federal ministry of a European country with a strong bureaucratic tradition for two years, following an embedded single case study design (Yin, 2018) and using abductive analysis to derive detailed insights from the qualitative data (Timmermans & Tavory, 2022). This allows for an in-depth qualitative exploration of two units of analysis, i.e., two innovation fellowships, within one public sector team. In this section I present the background and context of the case before providing insights into how the data was collected and analysed.

3.1Context and structure of the case

The fellowship programme I observed invites experts on agile methods into the public sector to collaborate with public servants on innovation projects for six months at a time. The goal is to bring agile practices into the public sector and help public servants explore them through practical application within a pre-defined setting. The fellowships provide a project format, in which public servants and external experts can learn from each other and test different forms and methods of collaboration that are not typically applied in the public sector.

Yin (2018) suggests presenting a longitudinal case study chronologically. To achieve this, I will present a quick overview of the fellowship’s general outline and its main actors, followed by a chronological structure to show how the collaborative process throughout the two observed iterations of the fellowships worked.

3.1.1The fellowship process and its actors

The participation in the fellowship is a voluntary action that public servants with small projects from their respective ministry could apply for, leading to a preselection of generally open and innovative participants from the public sector. Every project then was assigned to an external expert from the private sector, who was to work together with the public sector in the project and throughout this collaborative process, make the public servants familiar with innovative, especially agile, methods by applying them to problems and processes within their work. Many of the external experts had backgrounds in personal and organisational development with a wide array of expertise from working in start-ups or big companies. They applied privately, either given leave from work, being in-between jobs, or being self-employed, and wanting to enhance their knowledge about agile innovation in the public sector. While familiarity with agile methods was a prerequisite for the participation of the external experts, their regular job and organisation did not play a role in the decision to accept them as participants of the fellowship.

The application and adoption of agile methods were a focus of the fellowship. Depending on the needs of the team, agile methods like Kanban, stand-up meetings, or timeboxing (Diebold & Dahlem, 2014), among others, could be applied. The fellowship followed a broad understanding of agile, which is also a reason why agile practices was chosen as a key term in this research, instead of the more specific agile methods.

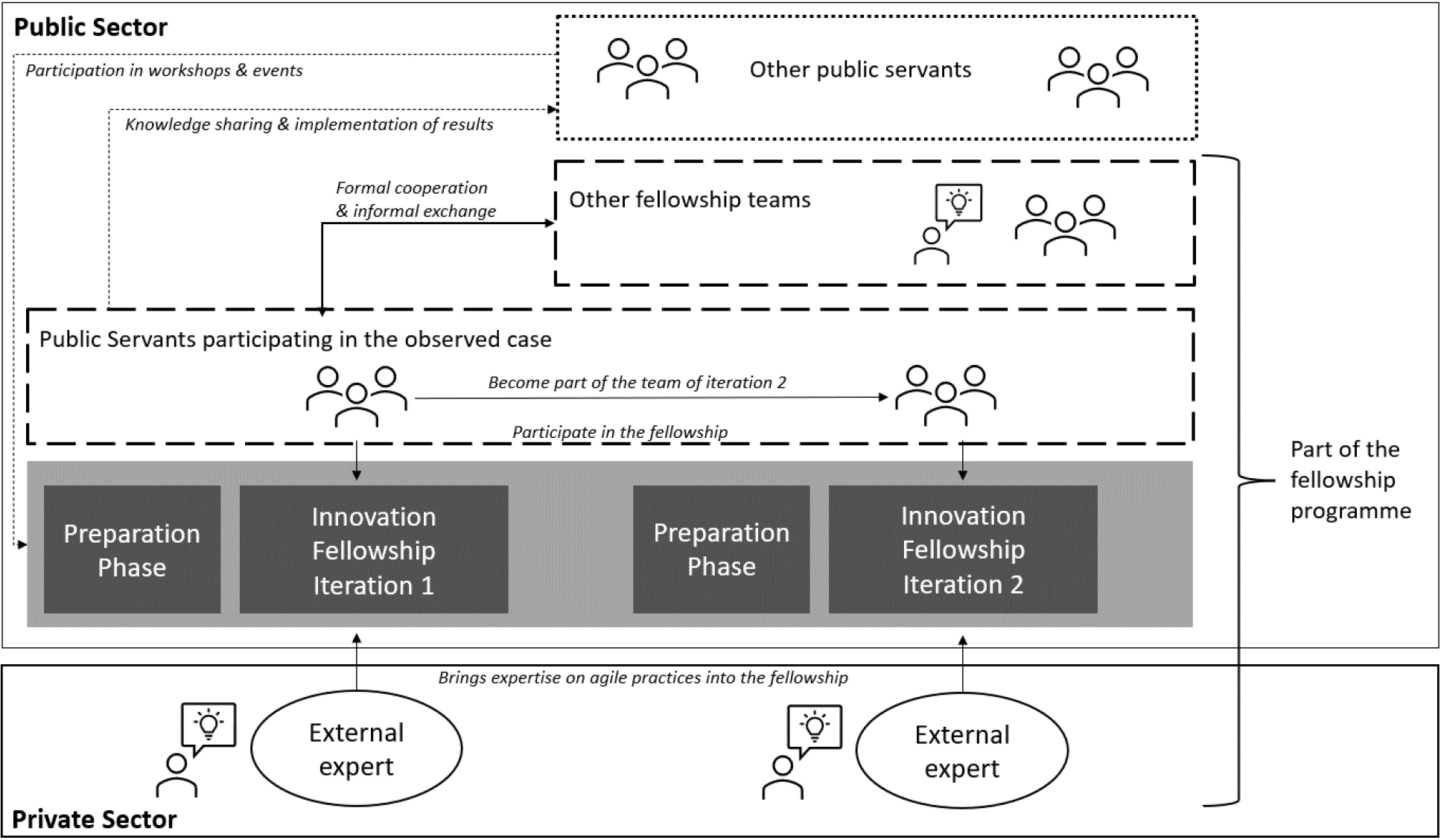

The programme was accompanied by a team from the agency in charge of the fellowship, who not only organised the programme itself, and matched external experts and public servants, but also permanently took feedback and used it to improve the next iteration of the programme. Throughout the six months of the fellowship participants were continually invited to reflect on their process, potential issues arising in the collaboration, and to acquire new skills that helped them conducting a successful project, framed by a kick-off and final presentation with all participants. Figure 1 provides an overview of this process, the actors, and their interactions throughout the innovation fellowship.

Figure 1.

Structure of the case and its participants. Own depiction.

As an external observer I examined two years, i.e., two iterations of the innovation fellowship, in 2021 and 2022 respectively, observing one public sector team in a federal ministry. The public sector team took part in the fellowship two times with different projects and fellows, but the same core team of public servants. The project team worked together with fellowship teams from within and outside their department. To show this process, I will present insights from the first iteration (labelled as year 1) before showing the developments in the second iteration of the fellowship (labelled as year 2).

3.1.2Year 1 of the innovation fellowship

In the first year of the innovation fellowship, the team from the observed case worked to improve the onboarding process within their organisation. Two public servants and one external expert participated in the innovation fellowship. Their primary objective during this period was the enhancement of the onboarding process within their organisational framework.

The public servants’ expectations for the collaboration throughout the fellowship were met and even exceeded. Despite initial difficulties emerging through a change of the external expert, the public servant team reported to have kept a positive attitude. The participation in this new format of bringing innovation into the public sector created a sense of excitement and enthusiasm among the group. As soon as the new external expert entered the team, the collaboration was reported as smooth and enriching. The team particularly appreciated the effectiveness of their collaboration, even though the process was embedded in some organisational challenges.

The fellowship took place in a hybrid setting, a necessity created by partial or full lockdowns throughout the six-month fellowship period as well as the distributed setting of workplaces within the team. While the external expert was situated in the capital, the public servants themselves worked in a different city. Since the department was spread across two different cities, the team faced the unique challenge of working together despite the physical distance. However, they successfully established a robust framework for collaboration, which was enhanced by several in-person meetings throughout the course of the six months.

The efforts of the fellowship team had a defined goal, resulting in a focus on employing user-centric methods. The public servants and the external expert highlighted interviews and focus groups they conducted in a short amount of time. Additionally, the external expert introduced the participants to new tools and methods, like daily stand-up meetings, timeboxing, Kanban and other collaborative practices. These tools and methods became integral parts of their daily work routines.

3.1.3Year 2 of the innovation fellowship

After the successful participation in the fellowship, the public servants applied again, with slight personnel changes in the team and a less concrete goal set for this iteration. The project focused on advancing the personnel development and after contacting another department from a different public sector organisation at the end of the first iteration of the innovation fellowship, it would be a collaborative effort between at least two fellowship teams. Each department hosted one external expert, resulting in three key areas of collaboration:

• collaboration between both public service units and external experts toward a shared objective,

• collaboration within each fellowship team, consisting of one external expert and several public servants each, and

• collaboration with other fellowship teams and public servants not participating in the fellowship programme through workshops and other events.

The initial project goal focused on the development and piloting of strategies to promote an agile mindset and corresponding competences in the context of personnel development. However, at the outset of the innovation fellowship it became evident that the specific goals of the two departments were not entirely aligned and required more precise definition. Both departments expressed the desire to foster an agile mindset and enhance collaboration but additionally decided to work on individual topics in the context of their own departments.

The external experts employed various methods to advance department-specific topics and convey agile competences. Workshops, research, and interviews conducted by the two innovation fellowship teams contributed to the development of content for the two department-specific themes. To achieve the common goal of applying and disseminating agile methods throughout the public service, a series of workshops and informational sessions were organized. These bi-weekly sessions attracted audiences from both departments, with external experts providing suggestions for repeating or institutionalizing this format. Regular weekly meetings facilitated the ongoing communication between external experts and public servants, and supplementary techniques such as Kanban and retrospectives were utilized as needed. Overall, the two external experts had a close collaboration, particularly during the preparation of jointly developed formats. Challenges throughout the process were addressed through improved communication and a clearer definition of goals.

3.2Data collection

The data was collected in the form of observations and interviews. The different methods allow a qualitative explorative approach with deep narrative insights into the topic at hand (Scholz & Tietje, 2002; Yin, 2018). At the start of every iteration of the fellowship programme the participants gave their informed consent to the study.

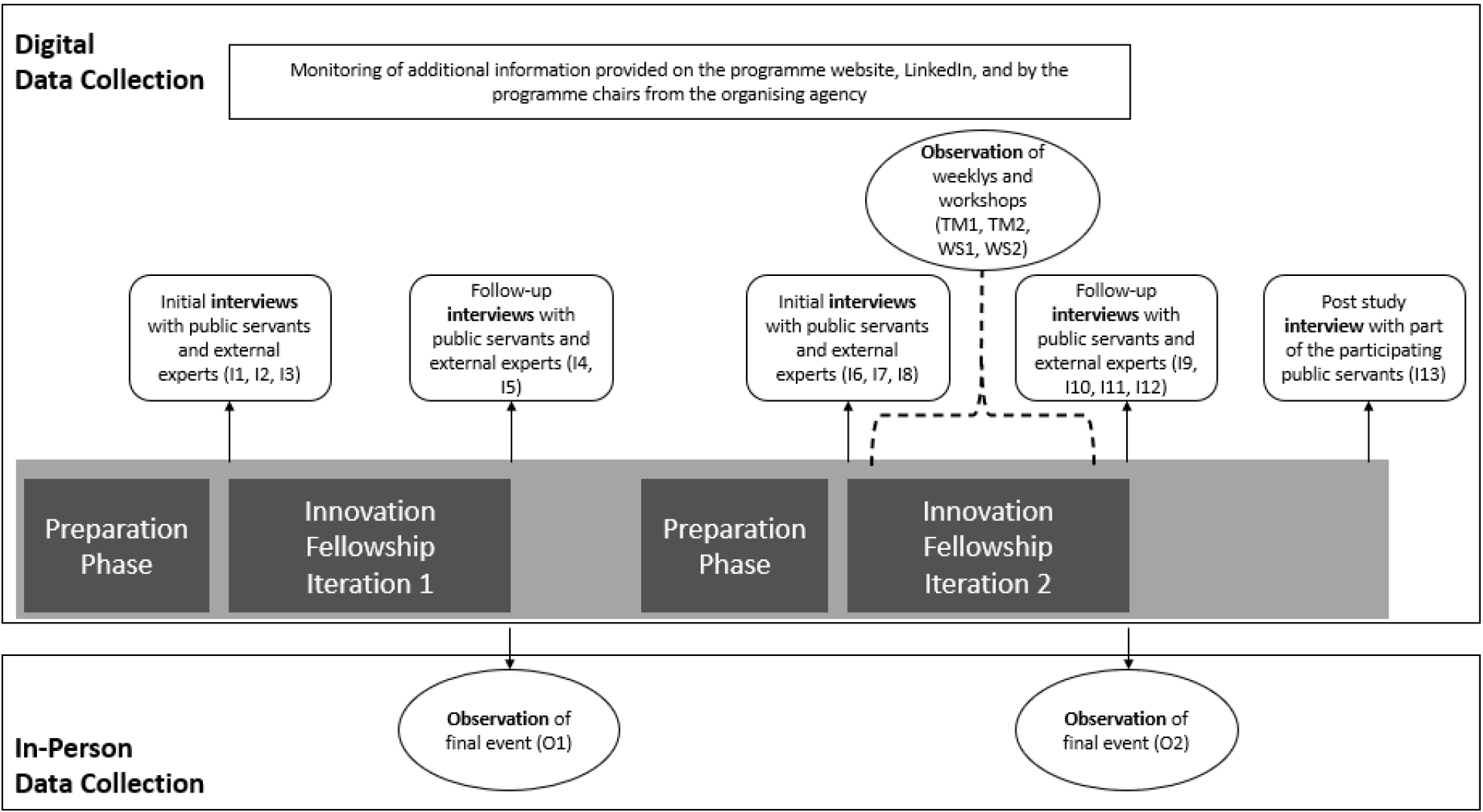

The active observation through participation in meetings and workshops is an essential part of public sector case studies in practice (Medina & Medina, 2017). Within my research I was able to observe two team meetings, two workshops as well as the two final presentations as a direct observer (Lüders, 2004; Yin, 2018). I attended the final presentation in person. All other observations were conducted online, via the digital platform the public service organisation used for their video communication. These observations were documented through observation protocols and additional field notes for the final presentations, handwritten notes were digitised after the observations. Altogether this resulted in six observation protocols with various lengths, dependent on the observed situation. The four observation protocols of team meetings and workshops documented formal aspects, such as the setting, duration, moderation, and number of participants, a description of the situation as well as content-related and atmospheric observations. The two observations of the final presentation described the overall setting and event in detail, with a special emphasis on the results and presentation of the observed fellowship team.

Interviews as a method often employed in qualitative public sector research and especially case studies can provide insights into explanations and personal understandings (Yin, 2018). Structured interviews with a duration between 25 to 75 minutes were mainly used to ask for the expectations, experiences, and learnings of the participants, following the tradition of Medina and Medina (2017) as well as Ferguson and Blackman (2019). These interviews took place at the start and end of the programme. Interviews with the external experts and public servants took place separately to allow for an open discussion. In the second year, the interviews were extended to another fellowship team who collaborated with the team from the studied case and also had prior experiences with the fellowship. Altogether, I conducted thirteen interviews over the two years, six of them with the public servants and seven with the external experts. Figure 2 shows an overview and timeline of the observations and interviews throughout the observational period.

Figure 2.

Overview of data sources throughout the examination period. Own depiction.

3.3Data analysis

To analyse the contents of the interview transcripts and observation protocols, I chose an abductive analysis approach. Abductive analysis allows to find surprises and generate theoretically useful insights from rich qualitative data (Timmermans & Tavory, 2022). It provides the opportunity for an explorative approach that allows for creative insights, mirroring the applied way of learning within the fellowship programme (Earl Rinehart, 2021). To achieve this, I followed Timmermans and Tavory’s (2022) approach of focused coding. Based on initial codes derived from the literature, a first overview of the data during the collection process, followed by a thorough reading of transcripts, I was able to derive and cluster themes within the data as qualitative codes. The codes were continually adapted throughout the coding process to account for new and surprising insights provided in the interviews. Table 1 shows the themes and codes used to analyse the interviews and observations.

Table 1

Overview of codes and their adaption throughout the process of analysis. Own Depiction

| Category (in relation to research question) | Concept | Code | Childcode |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1: | Agile competences | Self-reliance | |

| collaborative | Social competences | ||

| competences | Knowledge | ||

| Skills | |||

| Transformation competences | |||

| Other competences for the fellowship | Creativity | ||

| Openness | |||

| User-centricity | |||

| Communication | |||

| RQ2: informal | Challenges | Dealing with uncertainty | |

| learning process | New requirements for public servants | Developing new competences Applying new ways of working | |

| Organisational culture | |||

| Organisational framework | Organizational support | Support from team | |

| Support from management | |||

| Resources | Time | ||

| Personnel | |||

| Other resources | |||

| Learning process | Agile methods applied in fellowship | ||

| Learnings for public servants | Learnings mentioned explicitly | ||

| Learnings mentioned implicitly | |||

| RQ3: effect on the organisation | Long-term implementation of results | Application of agile practices | Outside the fellowship context After end of the fellowship |

| Implementation of results | Implementation of finished outcome | ||

| Further development of outcome | |||

| Collaboration | During the fellowship | In the team/department | |

| Outside the team/department | |||

| Outside the ministry | |||

| After the fellowship | In the team/department | ||

| Outside the team/department | |||

| Outside the ministry |

The structure comprising initial interviews, observations, and follow-up interviews not only clarified certain observations but also tracked shifting perceptions and methodological knowledge. The analysis was conducted with analogue modes (sticky notes for noteworthy themes and their clustering) and with the help of digital tools (NVIVO for coding, Obsidian for documenting context and connections) to harness the full potential of the coding process.

4.Findings

Throughout the interviews the participants of the programme provided evidence on the competences they developed and the framework conditions for the competence development. In this section I present the findings of the case study, including insights on the collaborative competences in the fellowship, drivers and barriers for the informal learning process, and finally the fellowship’s effects on the adoption of agile practices in the public sector.

4.1Developing collaborative competences throughout the fellowship

One of the central goals of the innovation fellowship programme is the development of methodological competences. However, public servants and external experts also defined certain skills as a prerequisite for participating in the fellowship: “Communication skills, curiosity, or openness to new things” (I5)11 together with a “willingness to learn, (…) a bit of courage” (I10), and long-term thinking were deemed competences that a public servant participating in the fellowship should have. External experts should especially bring openness and understanding towards the public sector as well as curiosity and proactivity. This was highlighted by the public servants, who expected a negative bias of the external experts towards the public sector. Overall, they perceived an impact of their learnings on the individual mindset and organisational culture: “And perhaps one must also have the courage, it ultimately involves a bit of a cultural shift, a change in attitude and such, which is difficult to measure and doesn’t happen overnight” (I11). Reflecting on which competences they developed was a difficulty for the public servants, since measuring competences like openness and communication is generally a difficult task (Heckman & Kautz, 2012), and explicitly articulating their learnings in the interviews posed a challenge for the public servants.

Still, due to their repeated participation in the fellowship, the public servants and their extended team were familiar with agile practices in the second year. Despite stating that not many new methods were learned or competences enhanced throughout the second iteration of the fellowship, the description of follow-up activities made it clear that the public servants (unconsciously) applied agile methods and processes within their work “and [that] the foundation for this has been laid with the fellowship” (I11). Additionally, participants were able to establish a long-term relationship and the basis for a better cross-departmental communication and collaboration: “One learning is indeed that the [fellowship] or any kind of collaboration is always beneficial because you simply have someone who can suddenly look at things from an external perspective” (I5).

4.2Drivers and barriers of informal learning in the fellowships

Especially in the first iteration, public servants involved in the fellowship reported that they acquired a solid understanding of and proficiency in the use of the tools and methods they were introduced to, such as Kanban, daily and weekly stand-ups or timeboxing. However, there were challenges in adopting some methods, especially in managing the flow of information and sticking to strict time schedules. Nevertheless, these challenges were seen as valuable learning experiences, as public servants highlighted the opportunity and need to put these learnings into action: “[I would like] to simply emphasise: try it out. Test, test, test” (I11).

Drivers. A key aspect the public servants highlighted was the active participation in the fellowship process: “I believe one must also take the time every now and then” (I12). Sufficient resources in the form of time and personnel, a positive perception of innovation and openness towards cultural change have been identified as success factors by the public servants. They mentioned the need for a different working culture and more openness for new methods and procedural changes among their colleagues. At the same time, the public servants perceived their own role of participants as multipliers in the organisation, which is supported by the far greater outreach of the activities in the second iteration of the programme.

The research has focused on individual experiences in the collaboration between the public servants and the external experts. But another driver mentioned was the support public servants received from within their organisation. Participants of the fellowship had an inherent motivation to partake in the process and implement their project. But to achieve this they needed support from superiors, which could range from general verbal support or sharing the project, to active advancement of the project. In the hierarchical public sector even a visible positive attitude of leaders could help embed the fellowship in the organisation and legitimise its results.

Barriers. Despite the prevailing success of the projects, they encountered a variety of barriers when trying to learn from each other:

• Communication, unclear goals, and different understandings: Most identified barriers stemmed from discrepancies in comprehension and communication. These challenges manifested in two distinct categories: external factors, such as vacations, holidays, differences in physical workplace locations, and other obligations complicated the exchange between public servants and external experts; and internal factors, characterised by variations in understanding or interpretation of key concepts, differences in individual backgrounds, and diverse cultural perspectives, which impeded the learning process.

• Organisational culture and perceived resistance to change: The public servants and the external experts repeatedly referred to the organisational culture as a potential threat to a successful innovation fellowship. Public servants mentioned the fear of resistance from other entities in the public sector. This perception, whether real or perceived, influenced decision-making and hindered the progress of the fellowships.

• Lack of time and other resources: The demands of day-to-day operational tasks constituted an additional barrier. These routine work responsibilities competed for time and resources with the innovation fellowship objectives. Conflicts could emerge when external experts were brought full-time into a collaborative project, while participating public servants might only be available for a few hours every week. At the same time, personnel changes might also disrupt a successful collaboration. In the second year the public servants tackled this by building a small team for their fellowship project, demonstrating the learning process in-between the fellowships. They highlight the need to dedicate resources to active participation: “So that’s really the most important point, more time. More time and more presence” (I5).

Table 2

Drivers and barriers for innovation fellowships. Own depiction

| Category | Drivers | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Communication | Communication of the fellowship throughout the organisation | Lack of communication, unclear goals, and different understandings |

| Culture | Organisational change and openness for new methods | Rigid organisational culture and perceived resistance to change |

| Resources | Formation of teams and networks around the fellowships | Lack of time and other resources and conflicts with daily operational demands |

| Support | Support throughout organisational hierarchies Collaboration with non-participants | Organisational hurdles for change and implementation of results |

Table 2 shows an overview of drivers and barriers of the informal learning process in the fellowship. Recognizing and addressing these barriers is essential for making successful collaboration and learning throughout the fellowships possible.

4.3Effects of the fellowships on the agility of the organisation

This project marked the first formal cross-sectoral cooperation within the fellowship programme. This cooperation was still ongoing and was being further developed at the end of the fellowship: “yes, we definitely want to continue working together and we now meet virtually every two weeks, and beyond that, we exchange updates on the current status [of our projects]” (I12). By inviting external experts into the public sector, the fellowship contributed to the understanding and adoption of agile practices and increased collaboration. Public servants highlight the increasing openness of their organisation as a key aspect of the fellowship: “So what’s also exciting for me is that we truly have a new approach here in the realm of administration, which is usually a very closed system and that we’re actually bringing in fresh ideas from the outside, trying to establish them” (I11).

In contrast to the understanding of these tools they showed in subsequent interviews and the optimism they portrayed throughout the second iteration of the fellowship, public servants expressed concern about the sustainability of implementing these new methods, especially in their regular work. They had reservations about how well these methods would work in the long term but at the same time highlighted the need for “what is always very important in public administration, an organisational sustainment” (I11).

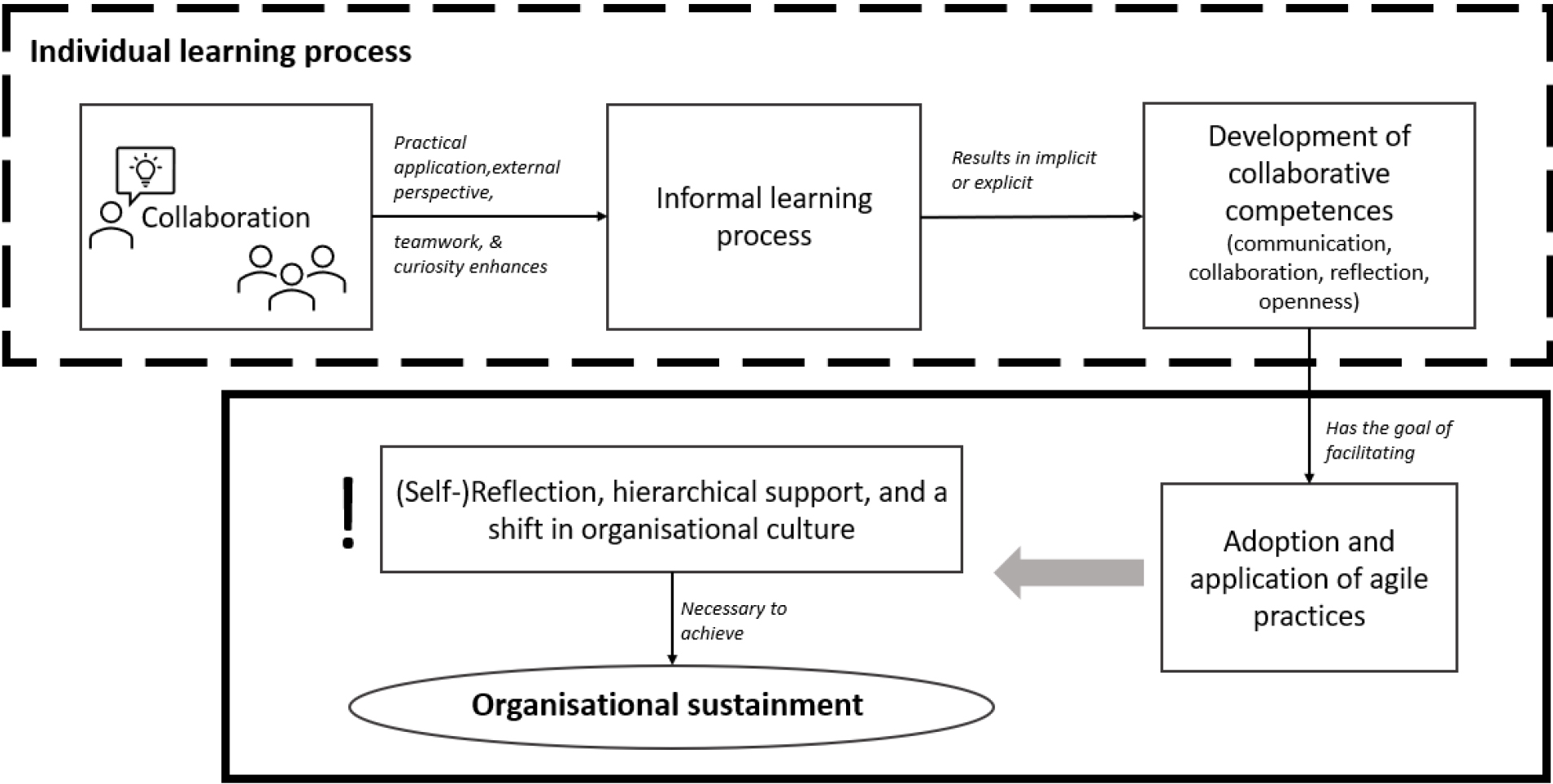

Figure 3.

Overview of the findings. Own depiction.

The consolidation of this process requires time, patience, and organisational networks. Figure 3 shows how collaboration in innovation fellowships fosters practice-oriented, reflected, and connected public servants, leading to individual learning, which again has positive effects towards a learning organisation. The felllowships make this application, reflection, and the formation of new networks possible, which leads to a learning process (Antonacopoulou, 2006; Prado et al., 2018), allows the development of new competences and, as a result, the implementation of agile practices.

5.Discussion

This study has shown the impact and dispersive effects of public servants’ participation in innovation fellowships. The presence, respectively absence, of certain drivers and barriers have the potential to create a collaborative process through which public servants can learn how to employ agile methods and develop collaborative competences. Especially the iterative participation in this process enables the creation of networks between teams within one public sector organisation and even the collaboration with other public sector organisations, a practice that can be new to many public servants.

So, how can public servants acquire collaborative competences that support agile practices in public organisations? The results of this case study show effects in three dimensions: the practical application of the learnings, in this case agile methods, in collaboration with external experts, the room for personal reflection, which is embedded into the structure of the innovation fellowships, and the formation of organisational networks, supported by a collaboration with other departments and events or informal exchange organised by the external experts. These factors are the basis for collaborative competences for agile organisations with the external experts as the central actors who bring in the expertise for change.

Collaboration with and learning from external experts are key elements for informal ways to develop collaborative competences in the public sector (Prado et al., 2018). Formats such as innovation fellowships can play an important role in creating these opportunities (le Clus, 2011), by providing a framework in which this collaboration may take place. The findings of this case study confirm the importance of informal formats to acquire competences in the public sector that has been suggested by Elsen et al. (2022). Within the fellowships, public servants got introduced and became used to formats and methods like stand-ups, Kanban, and iterative, user-centric project work. Openness, communication, and proactivity can prepare public servants to employ these agile practices.

One factor that stood out has been the implicitness of informal learning, which this case suggests. Public servants showed a constant reflection of their progress that has been facilitated by the framework of the fellowships, but also emerged through the application of agile methods. While the role of personal reflection for practitioners has been discussed in the literature before (Schön, 1987), the results show room for growth in this area. Public servants throughout the fellowship were able to critically reflect and improve issues arising in the communication and collaboration within the fellowship teams. They acknowledged the need for open communication and collaboration (Jeon & Kim, 2012). However, public servants did not report their own usage of methods acquired throughout the fellowship, even when the description of their work processes shows that they actively apply these methods after the end of the fellowships. Making this implicit knowledge explicit is a challenge for the public sector that needs to be tackled to provide a better understanding and application of the collaborative competences public servants possess and develop. Strengthening their ability to reflect not only on the collaborative process, but on individual learnings can become a key aspect in the conscious development of competences public servants need to adopt agile practices.

The process of developing collaborative competences leads to the second research question: Which drivers and barriers influence successful informal learning in public sector innovation fellowships? The fellowship teams encountered both drivers and barriers throughout the fellowship programme, concerning either the lack of or an improvement in communication, culture, resources, and organisational support. The specific nature of these drivers and barriers changed throughout the course of the fellowship iterations, showing that the participants were able to overcome and adapt to these conditions, providing the best framework for the innovation fellowship. The process of overcoming these barriers could in itself be a learning experience that enhances competence development. Innovation fellowships can provide a protected outlet for this process, allowing the public servants to make these experiences in a moderated process that they can later apply to other situations within their regular working environment. This working environment, and especially the organisational culture will often be the most contested point when opening such formats in the public sector (Cinar et al., 2019; Sørensen & Torfing, 2011).

To address the effects of the fellowships on public sector organisations, I asked the question: How does informal learning in innovation fellowships contribute to the adoption and application of agile practices in the public sector? As the findings of this case study have shown, all these aspects, i.e., informal learning, participation in innovation fellowships, and the subsequent adoption of agile practices, have an impact on the public sector and its culture. The implementation of agile practices in the public sector disrupts existing bureaucratic standards and necessitates a fundamental paradigm shift (Mergel, Ganapati, et al., 2021). Public servants participating in the innovation fellowship recognise the need for cultural change and openness in their organisation. These factors are impacted by the development of collaborative competences and the implementation of agile methods, affirming findings by Vries et al. (2016), Tripp et al. (2016), and Al Saifi (2015). They also highlight their own role as multiplicators of agile methods within their organisations, potentially laying the groundwork for new intra- and interorganisational communities of practice. But they show pessimism when talking about the long-term sustainability of integrating agile methods in the work practices of the public sector. External experts, although acknowledging the challenges presented by a bureaucratic hierarchy, seemed less pessimistic, at least in their evaluation of the difficulties emerging by the organisational culture in the public sector. This underlines their contribution not only of subject-specific knowledge, but also as moderators of the collaborative process who provide an outside perspective. Bringing these perspectives together, reflecting on learnings throughout the fellowship process and then sharing these learnings with other units throughout the public sector can contribute to a more reflected and effective adoption of agile practices.

6.Conclusion

In this case study I set out to explore how public servants can acquire collaborative competences through informal learning in an innovation fellowship to facilitate the adoption of agile practices in the public sector. I observed a public sector innovation fellowship, following an embedded single case study design by Yin (2018). My findings show that collaborative competences like communication, openness, and proactivity form the basis for a successful participation in the public sector innovation fellowships, providing relevant insights for practitioners. Collaboration with external experts can proof an essential tool for informal learning, but it requires additional measures to ensure that public servants not only employ their learnings implicitly, but also make them explicit. Additional case studies and ethnographies might be able to provide new insights into how competences developed in informal settings can be formalised.

This study contributes to the existing literature in three principal areas. First, it provides new empirical insights into informal learning through collaboration with external experts in the public sector, thus enriching existing literature that has focused on intraorganisational developments or the private sector. Second, built on Schön’s (1987) reflective practitioner, it highlights the need for reflection in the process of transforming implicit learning into explicit competences. Third, it shows the role of individual public servants as multiplicators within in their organisation. This may concern the individual participants of innovation fellowships or even leaders who show support and thus approval for the broader adoption of agile practices within the public sector. The long-term sustainment of competences has been identified as an important aspect for the success of informal learning in the public sector. This also paves the way for further quantitative and qualitative research to assess the long-term success of adopting agile practices following informal learning activities like innovation fellowships.

Despite these new insights there are also some limitations to this study. A single case study allows for detailed examinations of processual developments and personal experiences (Flyvbjerg, 2012) of public servants. Still, the capacity to generalise the results from this case study is limited. Participants themselves stated that they do not know if their experience and learnings are applicable for other government departments. This pessimistic attitude might also be linked to the self-selection within the fellowship programme. Since public servants, from their own motivation or that of their superiors, needed to apply for participation with their own projects, it can be assumed that the participants of the fellowships have a more open and innovative predisposition toward agile practices in comparison to their colleagues. If they themselves recognise this increased openness within their teams, participating public servants might not think that their less open colleagues would accept the use of new, for the public sector, agile practices, or even be able to reflect their learnings. However, throughout the fellowship the role of the participants as intraorganisational multiplicators has been highlighted, promising a more open and innovative public sector, if public servants are able to personal reflect and then communicate their acquired competences. The dichotomy between personal and communal experiences also raises the question, which effect this competence development has for public sector teams and how teams with the necessary collaborative competences can be created. Collaboration and informal learning processes are key elements in addressing these challenges and creating a more agile and innovative public sector.

Notes

1 For the legend of the interview references please see Fig. 2.

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded through the RTI-Strategy 2027 of Lower-Austria within the call RTI-Dissertations 2021 (FTI21-D-040) of the Gesellschaft für Forschungsförderung Niederösterreich (GFF). I thank Peter Parycek for his continued support as well as Ines Mergel, Noella Edelmann, and Thomas Lampoltshammer for their valuable feedback on early drafts of this study.

References

[1] | Al Saifi, S. A. ((2015) ). Positioning organisational culture in knowledge management research. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19: (2), 164-189. doi: 10.1108/JKM-07-2014-0287. |

[2] | Antonacopoulou, E. P. ((2006) ). The Relationship between Individual and Organizational Learning: New Evidence from Managerial Learning Practices. Management Learning, 37: (4), 455-473. |

[3] | Bancerz, M. ((2021) ). Exploring Collaborative Innovation Approaches AsCo-Production Policy Tools: Learning From Canada’s Agroecosystem Living LABS. International Public Management Review, 21: , 1-1. |

[4] | Bommert, B. ((2010) ). Collaborative innovation in the public sector. International Public Management Review, 11: (1), 15-33. |

[5] | Chinn, D., Hieronimus, S., Kirchherr, J., & Klier, J. ((2020) ). The future is now: Closing the skills gap in Europe’s public sector. https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20and%20social%20sector/our%20insights/the%20future%20is%20now%20closing%20the%20skills%20gap%20in%20europes%20public%20sector/the-future-is-now-closing-the-skills-gap-in-europes-public-sector-vf.pdf. |

[6] | Cinar, E., Trott, P., & Simms, C. ((2019) ). A systematic review of barriers to public sector innovation process. Public Management Review, 21: (2), 264-290. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1473477. |

[7] | Cunningham, J., & Hillier, E. ((2013) ). Informal learning in the workplace: Key activities and processes. Education + Training, 55: (1), 37-51. doi: 10.1108/00400911311294960. |

[8] | Diebold, P., & Dahlem, M. ((2014) ). Agile practices in practice: A mapping study. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, 1-10. |

[9] | Earl Rinehart, K. ((2021) ). Abductive analysis in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 27: (2), 303-311. |

[10] | Elsen, J., Vermeeren, B., & Steijn, B. ((2022) ). Valence of formal learning, employability and the moderating roles of transformational leadership and informal learning in the public sector. International Journal of Training and Development, 26: (2), 266-284. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12258. |

[11] | Ferguson, S., & Blackman, D. ((2019) ). Translating innovative practices into organizational knowledge in the public sector: A case study. Journal of Management & Organization, 25: (1), 42-57. |

[12] | Flyvbjerg, B. ((2012) ). Five misunderstandings about case study research, corrected. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice, London and New York: Routledge, 165-166. |

[13] | Getha-Taylor, H. ((2008) ). Reconsidering leadership theory and practice for collaborative governance: Examining the U.S. Coast Guard (Vol. 29). doi: 10.1016/S0163-786X(08)29006-3. |

[14] | Getha-Taylor, H., Blackmar, J., & Borry, E. L. ((2016) ). Are Competencies Universal or Situational? A State-Level Investigation of Collaborative Competencies. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36: (3), 306-320. Scopus. doi: 10.1177/0734371X15624132. |

[15] | Halvorsen, C. J., Nichols, E. L., & Oh, J. ((2023) ). The CoGenerate Innovation Fellowship: Supporting Leaders of Intergenerational Initiatives. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 0: (0), 1-8. doi: 10.1080/15350770.2023.2220707. |

[16] | Heckman, J. J., & Kautz, T. ((2012) ). Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics, 19: (4), 451-464. |

[17] | Hofstad, H., & Torfing, J. ((2015) ). Collaborative innovation as a tool forenvironmental, economic and social sustainability in regional governance. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 19: (4), Article 4. |

[18] | Ipe, M. ((2003) ). Knowledge Sharing in Organizations: A Conceptual Framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2: (4), 337-359. doi: 10.1177/1534484303257985. |

[19] | Jeon, K. S., & Kim, K.-N. ((2012) ). How do organizational and task factorsinfluence informal learning in the workplace? Human Resource Development International, 15: (2), 209-226. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2011.647463. |

[20] | Koivisto, J., Pohjola, P., & Pitkänen, N. ((2015) ). Systemic innovation model translated into public sector innovation practice. Innovation Journal, 20: (1-1). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84928942699&partnerID=40&md5=cbf38240a2a7e1d2408f2b2b518d5385. |

[21] | Kruyen, P. M., & Van Genugten, M. ((2020) ). Opening up the black box ofcivil servants’ competencies. Public Management Review, 22: (1), 118-140. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1638442. |

[22] | le Clus, M. ((2011) ). Informal learning in the workplace: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Adult Learning. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.436696242802320. |

[23] | Lüders, C. (2004). 1 From Participant Observation to Ethnography. A Companion to Qualitative Research, 1, 222. |

[24] | Malik, N. K., Khalil, G. I., Al Amoodi, A. Y., Bakhsh, M. A. S., & Sahwan, M. R. ((2021) ). Combatting Resistance to Change during the COVID 19 Pandemic with Design Thinking Approach: Making a Case for the Public Sector. 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), 658-663. |

[25] | Md. Rejab, M., Noble, J., & Marshall, S. ((2015) ). Coordinating Expertise Outside Agile Teams. In C. Lassenius, T. Dingsøyr, & M. Paasivaara (Eds.), Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming (pp. 141-153). Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18612-2_12. |

[26] | Medina, R., & Medina, A. ((2017) ). Managing competence and learning in knowledge-intensive, project-intensive organizations. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 10: (3), 505-526. doi: 10.1108/IJMPB-04-2016-0032. |

[27] | Mergel, I. ((2023) ). Social affordances of agile governance. Public Administration Review, n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1111/puar.13787. |

[28] | Mergel, I., Brahimi, A., & Hecht, S. ((2021) ). Agile Kompetenzen für die Digitalisierung der Verwaltung. Innovative Verwaltung, 10: , 28-31. |

[29] | Mergel, I., Ganapati, S., & Whitford, A. B. ((2021) ). Agile: A New Way of Governing. Public Administration Review, 81: (1), 161-165. doi: 10.1111/puar.13202. |

[30] | Mills, R., & Keremah, O. ((2020) ). Crisis Management And Organisational Agility: A Theoretical Review. 7: . |

[31] | Morse, R. S., & Stephens, J. B. ((2012) ). Teaching collaborative governance: Phases, competencies, and case-based learning. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 18: (3), 565-583. |

[32] | Moussa, M., McMurray, A., & Muenjohn, N. ((2018) ). Innovation in public sector organisations. Cogent Business & Management, 5: (1), 1475047-1475047. |

[33] | Nardelli, G., Jensen, J. O., & Nielsen, S. B. ((2015) ). Facilities management innovation in public-private collaborations: Danish ESCO projects. Journal of Facilities Management, 13: (2), 185-203. doi: 10.1108/JFM-04-2014-0012. |

[34] | Neumann Jr, R. K. ((1999) ). Donald Schon, the reflective practitioner, and the comparative failures of legal education. Clinical L. Rev., 6: , 401-401. |

[35] | Neumann, O., & Fischer, C. ((2023) ). Special Issue on The Future of Agile in Public Service Organizations: Macro, Meso and Micro Perspectives. |

[36] | Neumann, O., Kirklies, P. C., & Schott, C. (forthcoming). Adopting Agile in Public Administration. Public Management Review. |

[37] | Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., & Randma-Liiv, T. ((2011) ). Global Financial Crisis, Public Administration and Governance: Do New Problems Require New Solutions? Public Organization Review, 11: (1), 13-27. doi: 10.1007/s11115-010-0148-x. |

[38] | Prado, A. M., Pearson, A. A., & Bertelsen, N. S. ((2018) ). Management training in global health education: A Health Innovation Fellowship training program to bring healthcare to low-income communities in Central America. Global Health Action, 11: (1), 1408359-1408359. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1408359. |

[39] | Raut, P. K., Das, J. R., Gochhayat, J., & Das, K. P. ((2022) ). Influence of workforce agility on crisis management: Role of job characteristics and higher administrative support in public administration. Materials Today: Proceedings, 61: , 647-652. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.121. |

[40] | Ribeiro, A., & Domingues, L. ((2018) ). Acceptance of an agile methodology in the public sector. Procedia Computer Science, 138: , 621-629. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.083. |

[41] | Sanojca, E., & Eneau, J. ((2016) , January 1). Ambiguities of ‘collaborative competences’ in adult education. Collaborative competences and practices of innovation. 8th Triennial Conference of the European Society for Research on the Education of Adults (ESREA)? https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01681009; 8th Triennial Conference of the European Society for Research on the Education of Adults (ESREA), Sep 2016, Maynooth, Ireland. http://triennial2016.maynoothuniversity.ie/upload/files/Sanojca_E_Eneau_J.pdf, France, Europe. BASE. https://widgets.ebscohost.com/prod/customlink/hanapi/hanapi.php?profile=4dfs1q6ik8Gkxpmi19PnxO2T6eHNp8TblNXnk%2BHE5sfk3JDexevJ45%2FJ3dalx%2BTckKU%3D&DestinationURL=https%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dedsbas%26AN%3dedsbas.880F37CB%26lang%3dde%26site%3deds-live. |

[42] | Scholz, R. W., & Tietje, O. ((2002) ). Embedded case study methods: Integrating quantitative and qualitative knowledge. Sage. |

[43] | Schön, D. A. ((1987) ). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass. |

[44] | Skule, S. ((2004) ). Learning conditions at work: A framework to understand and assess informal learning in the workplace. International Journal of Training and Development, 8: (1), 8-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-3736.2004.00192.x. |

[45] | Smith, K.-A., Morassaei, S., Ruco, A., Bola, R., Currie, K. L., Cooper, N., & Prospero, L. D. ((2022) ). An evaluation of the impact for healthcare professionals after a leadership innovation fellowship program. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 53: (4, Supplement), S137–S144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2022.09.004. |

[46] | Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. ((2011) ). Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Administration and Society, 43: (8), 842-868. doi: 10.1177/0095399711418768. |

[47] | Suter, E., Arndt, J., Arthur, N., Parboosingh, J., Taylor, E., & Deutschlander, S. ((2009) ). Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 23: (1), 41-51. Scopus. doi: 10.1080/13561820802338579. |

[48] | Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. ((2022) ). Data analysis in qualitative research: Theorizing with abductive analysis. University of Chicago Press. |

[49] | Tripp, J., Riemenschneider, C., & Thatcher, J. ((2016) ). Job Satisfaction in Agile Development Teams: Agile Development as Work Redesign. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17: (4-4). doi: 10.17705/1jais.00426. |

[50] | Van der Wal, Z. ((2020) ). Being a Public Manager in Times of Crisis: The Art of Managing Stakeholders, Political Masters, and Collaborative Networks. Public Administration Review, 80: (5), 759-764. doi: 10.1111/puar.13245. |

[51] | van Helden, J., Grönlund, A., Mussari, R., & Ruggiero, P. ((2012) ). Exploring public sector managers’ preferences for attracting consultants or academics as external experts. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 9: (3), 205-227. doi: 10.1108/11766091211257443. |

[52] | Vries, H., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. ((2016) ). Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Administration, 94: (1), 146-166. |

[53] | Vuorikari, R., Kluzer, S., & Punie, Y. ((2022) ). DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens-With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Joint Research Centre (Seville site). |

[54] | Whitney, A. A. F. ((2018) ). Developing Creative Problem Solvers: A Case Study Examining a High-Impact Social Innovation Fellowship Program for Undergraduate Students – ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/openview/79f0608a694e9addfd228049a1b8c1ce/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar&parentSessionId=Mv2DJhH22mB63PbQ8sS4fkuZC3YV4VCqKjUQefi0q7E%3D. |

[55] | Yin, R. K. ((2018) ). Case study research and applications. Sage. |

[56] | Zakrzewska, M., Jarosz, S., & Soltysik, M. ((2020) ). The core of managerial competences in managing innovation projects. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology – Organization and Management Series, 2020: (148), 811-823. doi: 10.29119/1641-3466.2020.148.60. |

[57] | Zasa, F. P., Patrucco, A., & Pellizzoni, E. ((2020) ). Managing the Hybrid Organization: How Can Agile and Traditional Project Management Coexist? Research-Technology Management, 64: (1), 54-63. doi: 10.1080/08956308.2021.1843331 |

Appendices

Author biography

Valerie Albrecht is a PhD researcher at the University for Continuing Education Krems. Her studies focus on the competences public servants need for collaborative innovation. In addition, she works in projects with the public sector in the areas of innovation, future skills, co-creation, and digital strategies, usually employing a practice-oriented qualitative approach. She completed her master’s degree in Political Science, Administration and International Administration at Zeppelin University Friedrichshafen.