The 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment in the Era of a Planetary Crisis: Some Lessons for the Scholars and the Decision-makers

Abstract

The Stockholm+50 Conference (2-3 June 2022) has been perceived as a low-key affair and a missed opportunity. The moral halo that ushered the world into global environmental consciousness, led by the Prime Ministers of Sweden (Olof Palme) and India (Indira Gandhi) at the first UN Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) held in Stockholm (5–16 June 1972) seemed to be missing at the 2022 Stockholm+50 Conference. This historic event coincided with the 30th anniversary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Stockholm+50 event, jointly hosted by Sweden and Kenya, ended as a ubiquitous joint Presidents’ Final Remarks to the Plenary issued by the two host countries. In spite of the call for action by the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to address the “triple planetary crisis” driven by climate emergency, biodiversity loss and pollution and waste, the Stockholm+50 outcome took the shape of ten-point summarized recommendations. It didn’t cause any ripples or resulted in a clarion call that could shake the conscience of peoples and nations to arise for everting the existential planetary crisis. The 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment at best remained a timid acknowledgement of things going terribly wrong in the past fifty years (1972–2022). Yet, no world leader stepped forward to don the mantle “to rescue” the world from the “environmental mess” as urged by the UNSG in his 2 June 2022 inaugural address. The heads of government and delegations seemed to lack the requisite courage befitting the momentous occasion for a decisive course correction in the global environmental regulatory policies, legal instruments and the environmental governance architecture. What would it entail to address the planetary crisis? It brings to the fore some lessons from the 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment that presents an ideational challenge for scholars of International Law and International Relations as well as the UN system, multilateral environmental treaty processes, international institutions and the decision-makers of the sovereign states.

1Introduction

The Stockholm+50 Conference1 (2022 Stockholm Moment)2 was held to commemorate the fifty years of the 1972 Stockholm Conference (1972 Stockholm Moment)3 that “marked the beginning of the modern era of environmental awareness and action” and took the first “decisive step towards identifying the environment as a fundamental asset for the social and economic development of all countries”4. It also set the stage for addressing the global environmental problematique underscored in a series of scholarly studies preceding it.5

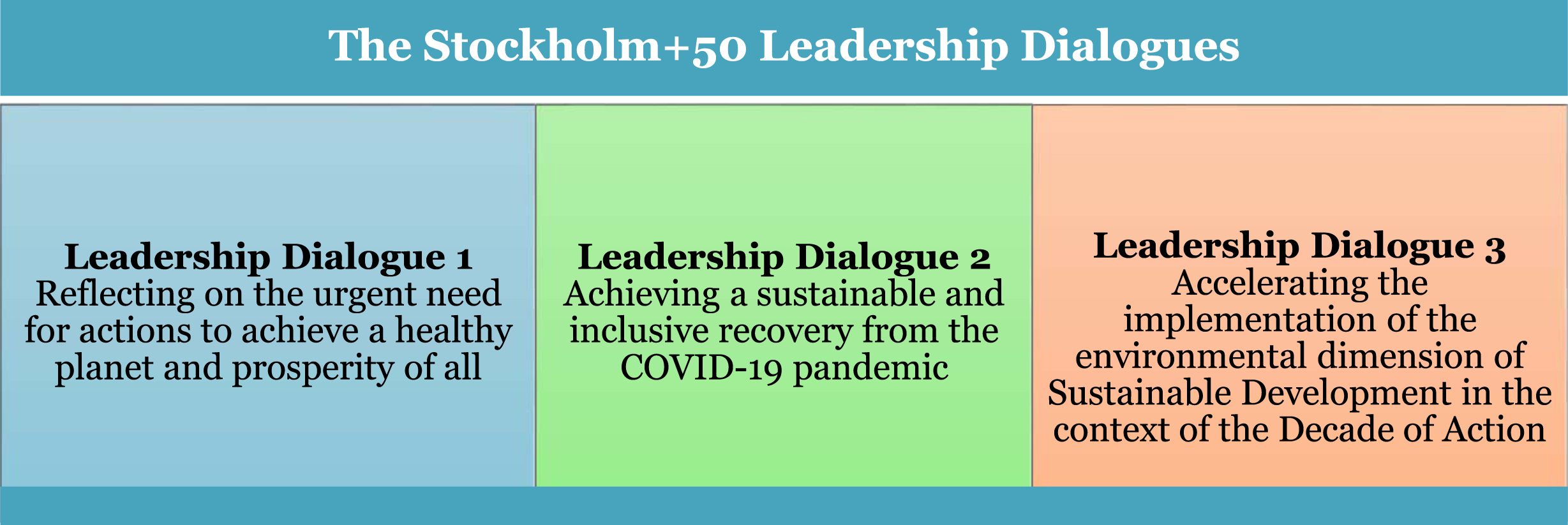

Thus, after a hiatus full 50 years, the world again assembled in the Swedish capital of Stockholm to take stock of the journey hitherto traversed and decide upon the future roadmap. The 2022 Stockholm Moment6 came at a critical juncture of the planetary level environmental crisis. Hence, it was legitimate to probe possibilities for a healthy planet and prosperous future so as to ensure that the human actions do not lead to irreversible consequences for the Earth. The running thread across the three leadership dialogues (Fig. 1)7,8 held in parallel with the plenary meetings, sought to underscore a deep sense

Fig. 1

The Stockholm+50 Leadership Dialogues.

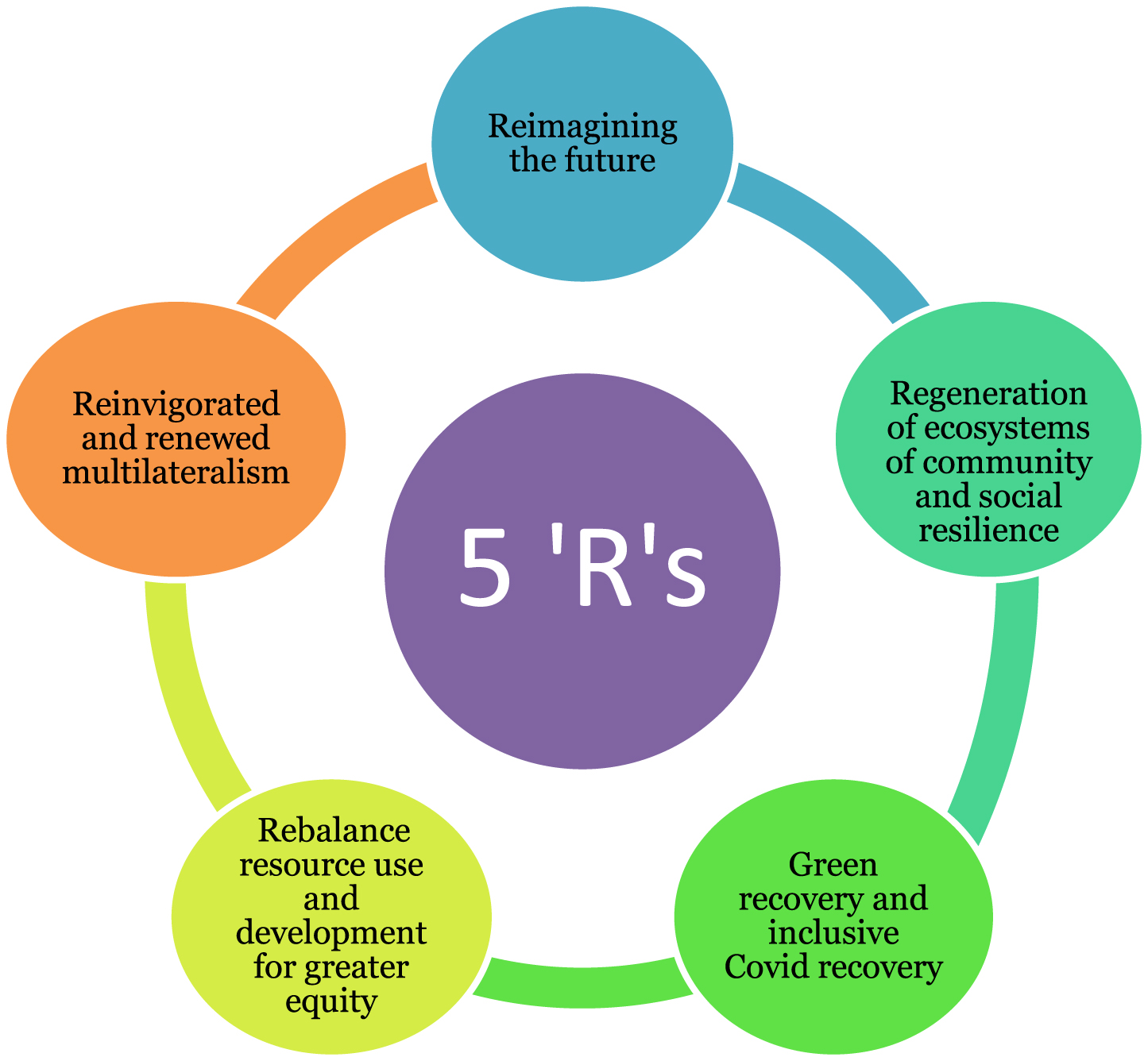

Fig. 2

Showing the Five Pathways for a Healthy Planet.

of urgency to reset our relationship with nature and to accelerate action to achieve all the pillars of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)9. The churning that took place under the banner of these concerted leadership dialogues during Stockholm+50 comprised the world leaders especially from the States, international organizations and other stakeholders including women, youth, older persons, persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and local communities. It provided an opportunity to examine actual working of the global environmental regulatory processes during the 1972–2022 period. For a long time, there have been scholarly concerns10 about threats to the global environment emanating largely from human actions that have now come to be confirmed in some of the authoritative scientific findings.11 The planetary crisis seems to be logical culmination of the human induced disequilibrium caused in the essential ecological processes of the Earth.

2The Stockhom+50 Moment

The stage was set for 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment by the UN General Assembly, through its two enabling12 as well as modalities13 resolutions, to examine as to how to achieve a sustainable and inclusive future for all. The concept note for the Stockholm+50 encapsulated the basis for it as follows:

Fifty years after the Stockholm conference, with increasing environmental challenges and growing inequality affecting development and well-being, the global community comes together to reflect on the urgent need for action to address these interconnections. Climate instability, biodiversity loss, chemical pollution, plastic waste, nitrogen overload, anti-microbial resistance and rising toxicity through reduced and altered ecosystem goods and services are unprecedented challenges for humanity. By harming health, eroding capabilities and limiting present and future development opportunities, these challenges are increasing human insecurity.14

A look back at the ‘act of origin’ (1972 Stockholm Conference) shows that a mammoth global regulatory enterprise has been at work to protect and preserve the environment. Notwithstanding this, there has been gradual environmental deterioration in all spheres. Growing scientific reports indicate signs of a serious planetary level environment crisis at work. The gathering clouds have made it clear that “unless we tackle the planetary crises, human actions will pull the proverbial rug out from under the feet of both society and the economy, which will result in further distress and insecurity”.15 Thus, the 2022 Stockholm Moment came amidst a pall of gloom as well as expectations that the assemblage of the sovereign States will rise to the occasion for a decisive course correction. It raised legitimate questions. What went wrong? Reminiscent of the “predicament”16 of humankind so vividly underscored in the 1972 Club of Rome report (Limits to Growth), the Stockholm+50 concept note also sought to chastise the sovereign states that:

“we can continue down the path of the last 50 years –characterized by unbalanced growth, unequal wealth, and unsustainable consumption and production, resulting in a degrading planet and growing inequity, ill-health, mistrust and hopelessness for the many and a good life for the few –or we can collectively pause and move forward with empathy and solidarity, anticipation and foresight towards collective action for a better future”.17

Thus, the 2022 Stockholm+50 Conference became a moment for a serious reflection as regards the future of humankind and very survival of life on the planet Earth. It also coincided with the 30th anniversary (4 June 2022) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Since global climate change has emerged as a plenary level crisis,18 it further added to the gravity of the situation for the Stockholm+50 event. Both the occasions heightened the expectations for concrete steps for fixing the inadequacies of the global regulatory processes as well as revitalizing the architecture of global environmental institutions. The historic 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment could have ushered the world into a much-needed new push for environmental awareness and decisive action in the next three-quarters of the 21st century, just as the 1972 Stockholm Moment did it five decades ago.

As mandated by the UN General Assembly, the Stockholm+50 event was convened by the Governments of Sweden and Kenya. This could have yielded commensurate responses for an emphatic course correction. The resultant outcome would have unleashed new ideas and new instrumentalities such as the repurposed UN Trusteeship Council19 as a global supervisory organ, working out the nuts and bolts of the circular economy, 20a reparative regime for climate-induced migration,21 finding solutions for climate change risk to the wetland ecosystem services22 and some dimensions of the planetary health challenges.23

3The Era of a Planetary Crisis

(i) The Genesis

It seems the humankind has not yet come to the grips with the predicament of striking a judicious balance between developmental needs and environmental imperatives. Much of the global development, profligate lifestyles, wasteful patterns of production and consumption and excessive natural resources extraction are not sustainable. The conflicting national positions and quest for material wealth litters the pathway in every part of the world. The graphic description of “two different worlds, two separate planets, two unequal humanities” (for the North-South divide) by the economist Mahbub-ul-Haq at the 1972 Stockholm Moment still haunts the world. He observed:

“In your world, there is a concern today about the quality of life; in our world, there is concern about life itself which is threatened by hunger and malnutrition. In your world, there is concern today about the conservation of non-renewable resources . . . In our world, the anxiety is not about the depletion of resources but about the best distribution and exploitation of these resources for the benefit of all mankind rather than for the benefit of a few nations. While you are worried about industrial pollution, we are worried about the pollution of poverty because our problems arise not out of excess of development and technology but because of lack of development and technology and inadequate control over natural phenomena”.24

The inherently exploitative developmental models and quest for material progress seems to have left far behind the Gandhian warnings (Hind Swaraj, 1908) about choice between our needs and greed as well as the lament of Tagore (1908) on “progress towards what and progress for whom”.25

As the world assembled again in the Swedish capital in 2022 after five decades, the echo of 6 June 1972 prediction of the then Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme reverberated:

“The decisive question is in which direction we will develop, by what means we will grow, which qualities we want to achieve, and what values we wish to guide our future . . . there is no individual future, neither for people nor for nations”.26

India holds the distinction for being present at the ‘act of origin’ of the 1972 Stockholm Moment, led by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The Indian delegation included three Cabinet Ministers (Karan Singh, C. Subramaniam, and I.K. Gujral). On 27 April 2022, Dr. Karan Singh, only surviving member of the 1972 Indian Delegation, shared his personal recollections with this author as follows:

“Indira Gandhi looked at the environment not from an elitist view point. She did it due to her genuine conviction that destruction of the natural habitat would not only adversely affect wildlife but ultimately the lives of the people living in the area. Her slogan to eliminate poverty, therefore, necessarily included the protection of our natural habitat as ordained in the ancient Indian tradition.”27

In her 1972 Stockholm address, Indira Gandhi drew a realistic global picture of the time by underscoring that the development is “one of the primary means of improving the environment of living, of providing food, water, sanitation and shelter, of making the deserts green and mountains habitable”. She further observed that “We have to prove to the disinherited majority of the world that ecology and conservation will not work against their interest but will bring an improvement in their lives.”28 She also drew attention to the ancient earthly wisdom from the Atharva Veda, thus:

What of thee I dig out, Let that quickly grow over, O Purifier, let me not hit thy vitals, Or thy heart29

Apart from the host country Prime Minister, the Indian Prime Minister was the only foreign head of government present out of 113 national delegations at the 1972 Stockholm Conference. The essence of Indira Gandhi’s Stockholm speech linked environmental conservation with poverty reduction. No wonder that it is now enshrined as Goal 1 (end poverty in all its forms everywhere)30 in the 2030 SDGs. It is also significant to recall the prophetic words of Olof Palme in his 06 June 1972 address. It was recalled by the Swedish PM Magdalena Andersson’s address on 02 June 2022:

“In relation to the human habitat, there is no individual future, neither for people nor for nations. Our future is common. We must share it together. We should shape it together”.31

It seems, the world has paid a heavy price in not taking Olof Palme as well as Indira Gandhi’s prophetic words seriously.

(ii) The Depleting Time

As mentioned in Section 2 above, the month of June 2022 came with a rare ‘environment week’ as it witnessed two back-to-back global environmental milestone events prior to the World Environment Day (05 June 2022)32 (i) 50th anniversary (2-3 June) of the 1972 UNCHE and (ii) 30th anniversary (04 June)33 of the UNFCCC. What did it portend for our common environmental future? In his inaugural address (02 June) at the Stockholm+50, the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres lamented about the “global wellbeing is in jeopardy”34, 02 June 2022; Rescue us from our environmental ‘mess’, UN chief urges Stockholm summit | UN News especially since “we have not kept our promises on the environment”, and graphically underscored the planetary crisis in these words:

Earth’s natural systems cannot keep up with our demands. We are consuming at the rate of 1.7 planets a year. If global consumption were at the level of the world’s richest countries, we would need more than three planet Earths. We face a triple planetary crisis. A climate emergency that is killing and displacing ever more people each year. Ecosystems degradation that are escalating the loss of biodiversity and compromising the well-being of more than 3 billion people. And a growing tide of pollution and waste that is costing some 9 million lives a year. We need to change course –now –and end our senseless and suicidal war against nature.35

Ironically, the UNSG’s call to the sovereign states to “lead us out of this mess” almost remained a cry in the wilderness. The “triple planetary crisis” referred by the UNSG comprises the climate induced migration and deaths, the loss of biodiversity threatening some three billion people and the global pollution and wastes that yearly costs some nine million lives. A commissioned UN study has candidly admitted that the planetary crisis of such a proportion “could not have been imagined in 1972”.36 Taking a cue from the UNSG’s anguish, Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN General Assembly’s environmental subsidiary organ (UNEP), minced no words to remind the Stockholm+50 audience about the inability to find answers to the global environmental problematique. Recalling the presence of only two heads of government at the 1972 UNCHE –India and Sweden –Andersen herself chose to pose a lingering question on what went wrong in five decades of the global regulatory enterprise:

“If Indira Gandhi or Olof Palme were here today, what excuses would we offer up for our inadequate action? None that they would accept. They would tell us that further inaction is inexcusable”.37

As Secretary-General of the 2022 Stockholm+50 Conference, Inger Andersen played the same role that Maurice Strong played at the 1972 Stockholm Conference. The above chastisement of Andersen became a somber and cathartic moment even as the state delegations looked back at the last fifty years (1972–2022) of the marathon global environmental regulatory enterprise. Prior to the actual event, the UN member states and other stakeholders met in New York in March 2022 to solidify the agenda and overall vision for the 2022 Conference. Apart from reiterating and reaffirming the ‘act of origin’ at the 1972 UNCHE, the Stockholm+50 process sought to further build upon the outcomes of all the previous major global conferences including the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and Agenda 21 (1992 UNCED)38., the Johannesburg Declaration and Plan of Action on Sustainable Development (2002 WSSD)39 and the “future we want” outcome document (2012 UNCSD).40 Thus, at least in letter, the Stockholm+50 event notionally swore that we must achieve a healthy planet for everyone, everywhere. The UNSG’s high pitched alarm “triple planetary crisis” did not cause any earth-shaking response from the Stockholm+50 gathering; still at the subterranean level none was oblivious to the grim reality of impending crisis that imperils the Earth and threatens the livelihoods and lives of billions of people.

Notwithstanding the gauntlet thrown by the feisty UNSG, ironically, no world leader stepped forward to go down in history by showing the courage to seize the moment.

In fact, the UNSG warned that “we are already perilously close to tipping points that could lead to cascading and irreversible climate effects.” The 2022 reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) validate that we’re running out of time to secure a sustainable future even as the global warming levels are more than double the 1.5°C limit above preindustrial levels. Hence, the Stockholm+50 could have been appropriately designed to accelerate processes for compliance with relevant MEAs so as to accomplish the goals of the 2030 SDGs, Paris Agreement, and Global Biodiversity Framework. As the aftermath of the 1972 Stockholm proved, if the world continues to work in silos, solution to environmental and climate challenges will become much more difficult. The only way to save the planet and ourselves from climate disaster is to look back while looking ahead together.41

(iii) The Climate Chaos

In this backdrop, the annual ritual of the UNFCCC COP27 (6–20 November 2022) at Sharm el-Sheikh (Egypt) also remained a low-key event. With 197 Parties, the UNFCCC has been designed as a ‘framework convention’. It became one of the first global instruments that designated climate change as a common concern of humankind. With subsequent two instruments, 1997 Kyoto Protocol and 2015 Paris agreement, the climate change regime now comprises three legal instruments that seek to address the global climate problematique. Yet there have been warning signs about shifting weather patterns that threaten food production, to rising sea levels that increase the risk of catastrophic flooding. The impacts of climate change are also unprecedented and on a planetary scale. Even as the stalemate continued past the last day of the COP27 and thousands of assembled delegations petered out of the conference venue, on 19 November 2022, the feisty UNSG again stepped in to renew his call for an urgent action and nudged the negotiators that:

“Climate chaos is a crisis of biblical proportions. The signs are everywhere. Instead of a burning bush, we face a burning planet. this conference has been driven by two overriding themes: justice and ambition. Justice for those on the frontlines who did so little to cause the crisis . . . Ambition to keep the 1.5-degree limit alive and pull humanity back from the climate cliff.”42

COP27 witnessed calls for payment overdue, sharp divisions, posturing and haggling among the different groups of countries to attain national interests rather than common interest. Even as the UNFCCC process completed 30 years (1992–2022) of its existence, the annual cycle of COP meeting left nagging questions as regards the evolution of the global climate change regime, the in-built law-making process, sincerity of the state parties in taking seriously the growing scientific evidence of human imprint for the climatic changes and effectiveness of the tools and techniques employed to address the challenge.

These scenarios and designation by the UNSG of the “triple planetary crisis”43, virtually elevated the UNFCCC’s raison d’être of a common concern to the level of a planetary concern. However, the current regulatory approach has been afflicted by the developed countries reneging from taking an effective lead due to their historical responsibility for the GHG emissions. The play of narrow national interests came to the fore in the hold-out flip-flops by the largest emitter –the United States of America –in withdrawal (2019)44 and rejoining (2021)45 of the 2015 Paris Agreement.46 It reflects vulnerability of a multilateral treaty process even as the climate crisis has assumed the form a planetary concern. The global regulatory framework appears floundering due to the (i) side-tracking of the UNFCCC’s sacrosanct principle of CBDR&RC (ii) grounding of the Kyoto Protocol applecart of Annex I legal obligations and (iii) the legal trick of pushing the developing countries into the NDC trap through the 2015 Paris Agreement. Ironically, as argued by some veteran negotiators, the developed countries have been “backtracking on almost every commitment made by them at the various Conference of Parties.”47

The 2022 IPCC48 sixth assessment report has shown that the world is not yet ready for measures to meet 1.5°C greenhouse gas (GHG) targets of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The 2022 Emissions Gap Report49 also confirmed that altogether, the latest Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) reduce the expected emissions in 2030 under current policies by only 5% whereas 30 or 45% reduction is required for 2.0°C or 1.5°C targets, respectively. The report suggested that if the climate action by countries is not scaled up, the world is likely to become warmer by 2.6°C by the end of the 21st century. What went wrong? 50

It has also been established that climate change has exacerbated sexual and gender-based violence against women. It is clear that heightened effects of SGBV due to climatic changes impose double economic burden on the States. In an ominous sign, in some countries, the cost of SGBV is staggering and it accounts for up to 3.7% of the GDP. Women bear the brunt of adverse effects of climate change induced violence during and after all the disasters, extreme events and conflicts. They are doubly victimized especially due to their gender. It calls for an urgent international (and national) legal and institutional mechanism to squarely address this emerging challenge.51

4The Stockholm+50 Outcome

The Stockholm+50 Conference remained a low-key affair. The outcome raised questions among the observers: “will it be remembered as little more than a nostalgic moment that will be overwhelmed by the weight of the 1972 Stockholm Conference’s struggle to bring something new into the world?”52 This comparison emanated in view of the moral halo that ushered the world into global environmental consciousness at the 1972 Stockholm Moment seemed to be missing at the 2022 Stockholm Moment. The UN meeting, jointly hosted by Sweden and Kenya, ended with a listless statement issued by the two host countries. Instead of the much-expected uplifting Stockholm+50 declaration, it took the shape of a strange ten point “Presidents’ Final Remarks to Plenary.”53 A key recommendation arising from the dialogues merely stated:

“Healthy planet is a prerequisite for peaceful, cohesive and prosperous societies; restoring our relationship with nature by integrating ethical values; and adopting a fundamental change in attitudes, habits, and behaviors, to support our common prosperity”.54

The 2022 Stockholm+50 outcome didn’t cause any ripple or issued a clarion call that could shake the conscience of peoples and nations to arise for everting the existential planetary crisis. The 2022 Stockholm Moment at best remained a timid acknowledgement of things going terribly wrong in the past fifty years. Yet it lacked the courage for a decisive course correction. The time seemed to stand still with the “world problematique”55 diagnosed in the 1972 Club of Rome report (Limits to Growth). Reminiscent of a routine conference statement, it came nowhere to the powerful call that arose from the 1972 Stockholm Declaration. The fact that the statement had to bank upon moral fabric speaks volumes about inability for “envisioning our environmental future”56 beyond the Stockholm+50 Conference. In this 2022 ideational work, an action-oriented outcome was envisioned that highlighted the future key actions that needed to be taken seriously by the governments and stakeholders. The ‘leadership dialogues’ were expected to sharpen and spell out in detail the targeted outcomes and the goals enlisted for the Stockholm+50. It was also suggested that outcomes of various global and regional processes could be brought together through five interconnected pathways (Figure 2)57 to chart a course in the post-Covid 19 pandemic (2020–2022) world beyond the Stockholm+50. That would possibly provide a framework for a healthy planet through regeneration of ecosystems, of community and social resilience; to address a green recovery and inclusive Covid recovery; to rebalance resource use and development.

After 50 years, the world has come a long way since the 1972 Stockholm Moment. Now, there are plethora of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs)58 > that cover most of the major sectoral environmental problems.

The 1972 Stockholm Conference had been organized at the 1968 initiative of Sweden to focus on human interactions with the environment. The UN Economic and Social Council adopted a resolution 1346 (XLV)59 It was duly endorsed by the UN General Assembly resolution 2398 (XXIII) of 3 December 1968 “to convene in 1972 a United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.”60 The choice of the UN system as the fulcrum was obvious since it is the only institutionalized global forum encasing political organization of the sovereign states. Over the years, the UN has put into practice the global conferencing technique. As a result, the Stockholm 1972 was followed by environmental confabulations in Rio de Janeiro (1992)61, Johannesburg (2002)62, Rio de Janeiro (2012)63 and now Stockholm (2022).64

On the one hand, celebrations of these environmental anniversaries show the penchant for the hypothesis that ‘global problems need global solutions’. Yet the global environmental conditions have only worsened over the years notwithstanding all the mega global conferences, regulatory processes, creation of institutional maze and spending of a staggering amount of funds. Was it really worth it? The world seems to be in dire straits as the 2030 SDGs65 are now set to go haywire, 2021 Global Hunger Index shows alarming situation of chronic hunger and the 2021 FAO report shows 842 million people suffering from chronic hunger and 2.37 billion people without access to adequate food.

As a consequence, the prognosis of the world we live in shows mindless quest for progress at the cost of foundational requirements for existence. Thus, the crisis at stake concerns not only wellbeing of the humankind but also the very survival of life on this only one Earth. The perilous pathways hitherto followed have only worsened the proverbial human predicament. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the stark reality emerged when this author’s audacious prediction in 1992 (published just prior to the Rio Earth Summit) became a vivid reality: “if the current pace persists, people will be forced to move with gas masks in some of the mega-cities in the not-too-distant future”.66 With 7.9 billion (2022)67 world population expected to reach frightening levels of 10 billion (2050), one can only imagine the kind of life the future generations will inherit. The words of late Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, expressed poetically in Hindi, amply show as to what ails us: “Human being has reached the moon but does not know how to live on the earth”! It was only logical culmination especially of the last fifty years journey that the UN SG gave a clarion call in his inaugural address (2 June 2022)68 at the Stockholm+50, for addressing the “triple planetary crisis” of climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste.

5Envisioning Our Future: Beyond Stockholm+50

It seems, the only two heads of government of Sweden (Olof Palme) and India (Indira Gandhi) present at the 1972 Stockholm Moment were ahead of their times. However, their warnings have been ignored at great peril to the humankind. After 50 years, as we look back, it is pertinent to assess the trajectory hitherto followed, what went wrong and how the world needs to move forward. An ideational book curated in 2022 for Stockholm+50 by this author, Envisioning Our Environmental Future69, painstakingly brought together futuristic ideas of outstanding scholars from around the world to look beyond the Stockholm+50. It has presented prognosis and prospects for ideas to extricate the world from the current global environmental morass for a better future in the 21st century and beyond. It is a sequel to another ideational work curated by the author in 2021: Our Earth Matters70. In the scholarly realm, we need to continue reflections upon the solutions for our better common environmental future in the era of a planetary crisis.

Incidentally, the address of the Indian Prime Minister, at the 75th anniversary of the UNGA (September 2020) emphasized that “we cannot fight today’s challenges with outdated structures.”71[dspd/2020/09/unga75/] He underscored the need for comprehensive UN reforms. An explicit reference to the trusteeship towards planet Earth72 in the address of the Indian Prime Minister at G-20 Riyadh virtual summit (2020)73 also provided one such indication in the realm of possibilities for much awaited restructuring of the UN. In fact, the UNSG’s 2021 report74 alluded to such reforms for the repurposed UNTC that was mooted in this author’s 15 January 1999 lecture75 at Legal Department of the World Bank DC. Will the UN member states embrace this idea to make the Trusteeship Council the principal instrumentality for the trusteeship of the planet?76. Hopefully, the Summit of the Future77 mandated by the UNGA to be held in New York (22-23 September 2024), and its proposed action-oriented outcome document –A Pact for the Future –would provide a concrete pathway for the UN to reinvent itself for the difficult times in the era of a planetary crisis.

There are difficulties in attaining consensus on future approaches and pathways for humankind’s predicament to address the existential crisis. In this wake, the best course of action would be soft international instrument that would still be taken seriously in the global decision-making processes. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights78 and the 1972 Stockholm Declaration79 provide the best two examples that ushered the world into a new era. In all such cases, the modality of the General Assembly resolutions provides the primary instrument for a defining moment. This is notwithstanding the big old scholarly debate on the legal character of the UNGA resolutions. As Asamoah explained the rationale:

The General Assembly, like other organs of the United Nations, interprets the Charter and other international agreements from day to day in connection with the performance of its functions. It also applies the principles of the Charter and other principles of international law when required by circumstances. In the absence of a compulsory adjudicatory process in the international legal order, political organs of the international organizations have to perform quasi-judicial service in discharging their functions.80

It is in this context that one needs to view the outcomes of the global conferencing techniques invoked by the UNGA. What is the normative value of the outcome of the Stockholm+50 meeting? The General Assembly had decided, in its resolution 75/326, that the rules relating to the procedure and the established practice of the General Assembly apply, mutatis mutandis, to the procedure of the international meeting.81 It was explicitly stated that the international meeting will have before it for adoption the provisional agenda (A/CONF.238/1), as recommended by the General Assembly in its resolution 75/326.82 The President’s Final Remarks to the Plenary highlighted to:

Reinforce and reinvigorate the multilateral system, through ensuring an effective rules-based multilateral system that supports countries in delivering on their national and global commitments, to ensure a fair and effective multilateralism; strengthening environmental rule of law, including by promoting convergence and synergies within the UN system and between Multilateral Environmental Agreements; strengthening the United Nations Environment Programme, in line with the UNEP@50 Political Declaration.

Take forward the Stockholm+50 outcomes, through reinforcing and reenergizing the ongoing international processes, including a global framework for biodiversity, an implementing agreement for the protection of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction, and the development of a new plastics convention; and engaging with the relevant conferences, such as the 2022 UN Ocean Conference, High Level Political Forum, the 27th Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the Summit of the Future.83

The 2022 Stockholm+50 highlighted the need for strengthening international environmental law. Still, it did not specifically come out with any hard instrument or concrete action plans to attain its agenda. Since the preparatory process itself did not have any enthusiasm for a concrete instrument and there was no big expectation for a splash to commemorate 50 years of the 1972 Stockholm Moment, the normative value of the outcome at best remained very low.84 Notwithstanding this, it matters most that the entire deliberative process was organized by the plenary organ of the UN, the General Assembly, the global conferencing technique was used as an instrumentality to address the planetary level environmental problematique and the Stockholm+50 had an explicit manmade of the UNGA [through enabling (75/280 of 24 May) and modalities (75/326 of 10 September) resolutions of 2021]. The underlying reasoning was to ensure that the “Stockholm+50 can be a moment for peace: it should demonstrate that multilateralism brings us together and can end conflicts that have set the world back for far too long. It must set the tone for equality, equity and respect in every area”.85 Hence, it was multilateralism at its best resulting in an inspirational outcome through a politically ordained process even if it was grossly inadequate in view of the gathering clouds of an existential planetary crisis.

The Stockholm+50 Moment could have at least helped in galvanizing the world for the implementation of the 2030 SDGs. Except formality of ritualistic statements by the delegations of the sovereign States, nothing transpired. At the same time, the stakeholders did much of the churning through the UNGA ordained three leadership dialogues. Thus, as mentioned earlier, the 2022 Stockholm Moment became a missed opportunity to come out with a clarion call for a decisive course correction “to rescue”86 the humankind from the planetary crisis. On 13 February 2023, it was testified again in the warnings of the UN Secretary-General in his address to the UNGA. He vividly showed the mirror to the UN member States on the SDGs that “halfway to 2030, we are far off track” as well as “on climate, on conflict, on inequality, on food insecurity, on nuclear weapons –we are closer to the edge than ever.”87 Even in the absence of any concrete hard or soft instruments, the 2022 Stockholm Moment could be said to embody the importance of multilateral cooperation and collaborative action in addressing the global environmental crisis of our times. In fact, the greatest strength of the resultant outcome of Presidents’ Final Remarks to Plenary88 (a ubiquitous statement comprising non-legally binding and inspirational or exhortatory expressions or phrases) is that it provided vital lubricant for functional cooperation between the sovereign states as well as reflected the views and concerns of some of the conscientious scholars and other stakeholders.

6The Lessons from Stockholm+50 Moment

Since 1972, the UNGA has played a crucial role in international environmental law-making as well as institution-building processes89. At each of the momentous occasions, at least in the environmental matters, the UNGA took crucial decisions that included convening of the major global conferences (1972, 1992, 2002, 2012 and 2022), established institutional structures (UNEP, CSD, HLPF and UNFF), took initiatives for launching inter-governmental negotiations (climate change, biodiversity, desertification) and provided mandates on several occasions for high-level informal consultations. As the plenary organ with all the UN member states, the Assembly has played its vanguard role to address the world environmental problematique with varied amount of successes. The fact that the UNGA provides a springboard for the UN member States for deliberations, records the needs, aspirations and concerns of the time and comes out with consensual outcome of resolutions (recommendatory) itself needs to be considered a blessing for the humankind. There is no other global forum at our disposal commanding such reach, trust and legitimacy.

(i) The Sleepwalking?

The 1972 Stockholm Moment was an outcome of the initiative of the Swedish Government and the resultant outcome, though under the UN auspices, had a strong Stockholm imprint. In contrast, the 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment was enabled by the UNGA through resolution 75/280 (“Sweden to host and assume the cost” and “with the support of Kenya”) as well as mandated by resolution 75/326 (“Sweden to host and assume the cost”; “with the support of Kenya”; “two Presidents, one from Sweden and one from Kenya”). These resolutions explicitly made the Swedish Government share the credits with the Kenyan Government. It was also expected that the “international meeting should be mutually reinforcing with UNEP@50, avoiding overlap and duplication”. Moreover, the UNGA required “the United Nations Environment Programme to serve as the focal point for providing support to the organization of the international meeting” and suggested to the Secretary-General “to appoint the Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme as the Secretary-General of the international meeting”. It was also curious that commemoration of the 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment was parceled into two parts for a mere two-day event across two continents: (i) UNEP@50 in Nairobi, 3-4 March 2022 and (ii) Stockholm+50 in Stockholm, 2-3 June 2022.

Cumulatively, in essence, the stage set inherently was robbed off the luster as regards the historical significance of the 2022 Stockhom+50 Moment. Possibly, keeping in mind the ground reality of the much-divided world, it showed that the effort was to be ‘politically correct’ rather than seize the Stockholm+50 Moment to ordain a rigorous review of the international environmental legal instruments as well as the international environmental governance architecture including structure, performance and location of UNEP. At the ‘act of origin’ (1972 Stockholm Moment), the deliberations were spread over 5–16 June whereas only two days were given for the 50-year commemorative event (2022 Stockholm+50). Hence, nothing concrete could be expected except ritualistic sermons and inspirational statements. The UNSG’s repeated laments at Stockholm+50 and the UNGA speak volumes about the unpreparedness (and possibly even fatigue effect) of the member States that were far removed from any seriousness to grapple with a planetary crisis staring at the humankind and the Earth. Yet the sheer presence of the feisty UNSG has been a silver lining, almost akin to the plight of the lonely House Sparrow who ran from the pillar to the post by sprinkling little drops of water when her own forest was on fire! Is the world slowly sleepwalking into the unimaginable planetary crisis?

(ii) The UNGA Needs to Takes the Charge

It now appears, in the aftermath of the outcome of the 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment and in view of the gravity of a planetary crisis, the UNGA needs to rise to the occasion to take charge of the situation. The UNGA has already set the stage for Summit of the Future90 (UNGA resolution 76/307 of 8 September 2022) to be held in New York during 22-23 September 2024. As a corollary, the Assembly needs to chart the future roadmap to institutionalize the review, establish synergy and inter-linkages as well as determine the trajectory of some of the principal MEAs (with universal membership, such as UNFCCC, UNCCD and CBD) as well as determine the design of the environmental governance architecture that is warranted for the challenges of our times. At the minimum, to begin with, the UNGA needs to address at least three processes that would be least-cost and not require any de novo institutional changes as follows:

(a) Since 1988, the UNGA has been the principal conductor of the grand climate-change orchestra, invoking the normativity of ‘common concern’ (resolution 43/53 of 8 December 1988) which brought into being the UNEP-WMO joint mechanism of IPCC (UNGA resolution 43/53 of 1988, paragraph 5) and triggered the process for negotiations (1990–1992) for the UNFCCC. Therefore, it is high time for the UNGA to rise to the occasion and elevate that common concern to the higher pedestal of a planetary concern. In view of the gravity of the climatic challenge, the UNGA needs to take charge by adopting an appropriate normative resolution during the 77th session and beyond to provide future direction to the 1992 UNFCCC and 2015 Paris Agreement processes. Even though COP27 (2022) adopted the decision on ‘loss and damage’ funding for those vulnerable countries hit hardest by climate disasters, it will take years to flesh out the mechanism and ensure the requisite funding would be provided by the concerned countries. However, the previous experiences of such climate funding commitments do not augur well. As we look ahead, the future trajectory of the climate-change regulatory process remains uncertain. It presents an ideational challenge for the international law scholars, the UN General Assembly and the UNFCCC regulatory process to earnestly make it work by elevating the normative ambit of climate change regulation as a planetary concern.91, 14 February 2023; Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-makers — Green Diplomacy

(b) A product of the 1972 Stockholm Moment, UNEP has been working as a subsidiary organ of the UNGA as an environmental program. There has been much discussion among the scholars and the decision-makers to elevate the current programmatic format of UNEP. Since the 1998 Klaus Toepfer Task Report, several exercises have been undertaken to boost its institutional status within the UN system. This author, in an invited talk on 15 January 1999 at Legal Department of the World Bank, called for UNEP’s upgradation as UN Environment Protection Organization (UNEPO)92. Notwithstanding change in nomenclature as UNEA (in place of the Governing Council) and universal membership, UNEP remains trapped in the quagmire of a program and its location has often posed practical challenges. Since, UNEP is still not a full-fledged international organization, it is high time to finally confer on it the status of a UN ‘specialized agency’. Such an entity, as an international environmental organization, would be better equipped to address the global environmental challenges, contribute to international environment law-making processes and bring other institutional actors on board.

(c) Along with the final up-gradation of UNEP as a ‘specialized agency’ (UNEPO), UNEP, there is a need to revive and repurpose the UNTC to look after the need and actions of the present and future generation for the conservation and protection of the global environment and the ‘global commons.’93 In 2021, the UNSG Antonio Guterres suggested in his report Our Common Agenda94 that the UNTC needs to be repurposed as a deliberative forum on behalf of the present and the future generations. The UNSG report has provided a fresh impetus to the long pending demand for revival and repurpose of the UNTC. It came at a time when the world was getting ready for the 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment. The UNTC could be entrusted with the task of supervising the scattered legal regimes for environmental protection as well as the global commons. In fact, it could share the tasks of the other two overburdened principal UN organs — the UNGA and the ECOSOC. It would serve as the UN system’s in-house global supervisory organ for environment, commons and sustainable development. It will also obviate the need for new funding demands and creation of a de novo institutional structure.

7Conclusion

As already seen, notwithstanding all the pious declarations, international instruments and institutional maze, the global environmental conditions have reached a perilous state. The UN Secretary-General António Guterres described the triple planetary crisis as “our number one existential threat” that needs “an urgent, all-out effort to turn things around.”95 Similarly, Inger Andersen, UNEP executive director and the Secretary-General of Stockholm+50,96 underscored that “If we do not change, the triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste will only accelerate.” The General Assembly President Abdulla Shahid also reminded at 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment that the policies we implement today will shape the world we live in tomorrow since the “human progress cannot occur on an earth that is starved of its own resources, marred by pollution, and is under relentless assault from a climate crisis of its own making.”97

Therefore, the Stockholm+50 as a missed opportunity, provides vital lessons for the scholars of international law and international relations to think aloud and ahead for our better common environmental future. In order to save the humankind and the planet from a planetary crisis, we will need cutting-edge ideational solutions. In the realm of such possibilities, it was a humbling experience for this author to reach out during the most difficult Covid-19 pandemic period (2020–2022) to the outstanding thought leaders from around the world. Through back-to-back three special issues of EPL [(i) vol.52 (5-6) 2022; (ii) vol.52 (1-2-3-4) 2022; (iii) vol. 51 (1-2) 2021 and vol. 50 (6) 2020], the harvesting of the ideas yielded rich corpus of 55 research papers that have also been separately published in the book form by IOS Press98. It amply underscores that at a time of such a planetary crisis, it is possible for the conscientious scholars to seed ideational solutions to save us from the brink. The onus remains on the decision-makers of the sovereign States, the UN system, multilateral treaty frameworks and other international institutions to translate these timely ideas into action to save the humankind from a planetary crisis. On the road to the 2024 Summit of the Future, there would still be room for terrain mapping so as to engage in greater scholarly churning.

There is an urgent need for radical overhaul of the UN’s environmental architecture. In spite of the scholarly audacity for ideas such as final upgradation of the UNEP into a ‘specialized agency’ called UNEPO as well as the revival and repurpose of the UNTC at this critical juncture, one is alive to the need for crucial political support from the UN member states. Due to lack of appetite for radical changes unless there is an imminent risk forced by a trigger event, the sovereign States may be wary of such ambitious futuristic processes even if they do not require any additional costs or de novo institutions.

In the past, states have been generally unwilling to build powerful institutions and give them stronger repurpose due to perceived fears about their national interests. The UN itself has often witnessed motivated bashing, the squeezing of annual contributions and pressures for ‘restructuring’ to suit the interests of some countries and even threats for withdrawals. Notwithstanding this, sovereign states, as primary subjects of international law, continue to be the final arbiters of the strength and authority of international environmental institutions and the global commons areas since ‘the action gap’ appears to be very significant.99

The 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment provided a unique opportunity to all the heads of government to go down in history. Unlike the leadership of Olof Palme and Indira Gandhi at 1972 Stockholm Moment, ironically, no world leader stepped forward at 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment to don the mantle to lead the planet out of the crisis of survival. As we saw during the grueling spell of Covid-19 pandemic (2020–2022), Nature has her own ways of drawing the ‘limits’ to our existence on this beleaguered planet. Maybe it was a wakeup call. As the countdown to the forthcoming 2024 New York Summit of the Future100 has began, onus remains on the scholars and the decision-makers to prepare and make the best use of that opportunity for a decisive course correction to avert a planetary crisis.101 Time is the essence. We can only hope that “peoples and nations come to the senses before the rapidly ‘depleting’ Time itself runs out”.102

Notes

1 Stockholm+50 (2022), Stockholm+50: A Healthy Planet for the Prosperity of All –Our Responsibility, Our Opportunity, Stockholm, Sweden 2-3 June 2022; Stockholm+50 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

2 At the Stockholm+50 Conference (2-3 June 2022), a commemorative moment was officially dedicated to the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE), held in Stockholm from 5 to 16 June 1972. It was held at 9 a.m. on 2 June 2022 in the plenary hall of Stockholmsmässan (located at Mässvägen 1, Älvsjö, Stockholm), prior to the official opening of the Stockholm+50 Conference; see UN (2022), Organizational and procedural matters, Doc. A/238/2 of 27 April 2022; A/CONF.238/2 (undocs.org)

3 UN (1972), Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, 5-16 June 1972; A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1; United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm 1972 | United Nations.

4 UN (2022), Report: Stockholm+50, Stockholm, 2-3 June 2022; UN Doc. A/CONF. 238/9, 1 August 2022; A/CONF.238/9 (undocs.org).

5 The pioneering scholarly studies include: Rachel Carson (1962), Silent Spring (Houghton Mifflin); Richard A Falk (1971), This Endangered Planet: Prospects and Proposals for Human Survival (New York: Vintage Books); Donella H Meadows et al. (1972), The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome on the Predicament of Mankind (New York: Universe Books); Barbara Ward and Rene Dubos (1972), Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet (New York: W.W. Norton).

6 Bharat H Desai (2022), “The Stockholm Moment”, Preface, Environmental Policy and Law 52 (2022) 171–172; available at: The Stockholm Moment - IOS Press

7 UN (2022), Stockholm+50 Documents: Organizational and Procedural; 27 April 2022: A/CONF. 238/2; Documents | Stockholm+50

8 UN (2022), Stockholm+50 Leadership Dialogues: Emerging recommendations and key messages to achieve a healthy planet and prosperity for all; available at: Documents ∥ Stockholm+50.

9 UN (2015), Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; General Assembly resolution 70/1 of 25 September 2015; available at: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs (un.org)

10 Bharat H Desai (1992), “Threats to the world eco-system: A Role for the Social Scientists”, Social Science & Medicine (Elsevier), vol. 35, no. 4, 1992, pp. 589-96; available at: Threats to the world eco-system: A role for the social scientists - ScienceDirect. Also see Bharat H Desai (1986), “Destroying the Global Environment: We are all Potential Environmental Refugees”, International Perspectives (Ottawa), Department of External Affairs, Canada, November-December, 1986, pp. 27-29.

11 IPCC (2022), Sixth Assessment Report: Working Group I (9 August 2021); Working Group II (28 February 2022); Working Group III (4 April 2022); available at: Sixth Assessment Report — IPCC

12 UN (2021), “International meeting entitled “Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all –our responsibility, our opportunity", General Assembly resolution 75/280 of 24 May 2021; available at: Resolutions of the 75th Session - UN General Assembly

13 UN (2021), “Modalities for the international meeting entitled “Stockholm+50: a Healthy Planet for the Prosperity of All - our Responsibility, our Opportunity”, General Assembly resolution 75/326 of 10 September 2021; Resolutions of the 75th Session - UN General Assembly

14 UN (2022), Concept Note: Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all –our responsibility, our opportunity, paragraph 5, p.2; UN Doc. A/CONF./238. 3, 31 March 2022; A/CONF.238/3 (undocs.org)

15 Ibid, paragraph 6, p.3.

16 The foreword to the 1972 report of the Club of Rome –Limits to Growth –by William Watts, President of Potomac Associates to famously stated: “It is the predicament of mankind that man can perceive the problematique, yet, despite his considerable knowledge and skills, he does not understand the origins, significance, and interrelationships of its many components and thus is unable to devise effective responses. This failure occurs in large part because we continue to examine single items in the problematique without understanding that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, that change in one element means change in the others”; see Donella H Meadows et al. (1972), p. 5, n.5.

17 UN (2022), n.14, paragraph 8, p.3.

18 Bharat H. Desai (2023), “Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-up Call for the Decision-makers”; EPL Blog, 05 January 2023; Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-makers | Environmental Policy and Law; Bharat H Desai (2022), “Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern”, Environmental Policy and Law vol. 52, no. 5-6, 2022, pp.331-347; Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern - IOS Press.

19 Bharat H Desai (2022), “The Repurposed UN Trusteeship Council for the Future”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol.52, no.3-4, pp.223-235; The Repurposed UN Trusteeship Council for the Future - IOS Press

20 Chris Backes and Marion Boeve (2022), “Envisioning the Future of the Circular Economy: A Legal Perspective”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no.3-4, pp.253-263; Envisioning the Future of the Circular Economy: A Legal Perspective - IOS Press

21 Kirk W. Junker et al. (2022), A Question of Trust: Building a Reparative Legal Regime in the Face of Climate-Induced Migration”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no.3-4, pp.265-276; A Question of Trust: Building a Reparative Legal Regime in the Face of Climate-Induced Migration - IOS Press

22 Shailesh Nayak (2022), “Factoring Climate Change Risks in the Wetland Ecosystems Governance: A Policy Look Ahead”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no.3-4, pp.277-288; Factoring Climate Change Risks in the Wetland Ecosystems Governance: A Policy Look Ahead + - IOS Press

23 Philippe Cullet et al. (2022), “The Regulation of Planetary Health Challenges: A Co-Benefits Approach for AMR and WASH”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no.3-4, pp.289-299; The Regulation of Planetary Health Challenges: A Co-Benefits Approach for AMR and WASH - IOS Press

24 Bharat H Desai (2013), “Environment and Development: Making Sense of Predicament of the Developing Countries”, World Focus, May 2013, p.4; (7) (PDF) ENVIRONMENT & DEVELOPMENT: MAKING SENSE OF PREDICAMENT OF THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES ENVIRONMENT & DEVELOPMENT: MAKING SENSE OF PREDICAMENT OF THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES (researchgate.net). Also see, Mahbub ul Haq (1976), The Poverty Curtain: Choices for the Third World, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 82.

25 Soares Anthony X. (1928), “Lectures and Addresses Rabindra Nath Tagore Selected from the Speeches of the Poet,” Macmillan: London, available at: Lectures and Addresses Rabindranath Tagore | INDIAN CULTURE Excerpts: Lectures and Addresses by Rabindranath Tagore and Anthony Xavier Soares (ed) (iitk.ac.in).

26 Anna Sundstrom (2021), “Looking through Palme’s Vision for the Global Environment” in Bharat H Desai, Ed., Our Earth Matters: Pathways to a Better Common Environmental Future (Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2021), pp.175-182; Our Earth Matters | IOS Press

27 Karan Singh (2022), “Looking through Indira Gandhi’s Vision: Some Personal Recollections” in Bharat H Desai, Ed., Envisioning Environmental Future: Stockholm+50 and beyond (Amsterdam, Berlin, Washington DC: IOS Press, 2022), Chapter 4, pp.29-33; Envisioning Our Environmental Future | IOS Press

28 UNEP (2022), “India is key to the success of Stockholm+50, as it was in 1972”; https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/opinion/india-key-success-stockholm50-it-was-1972

29 The original full Sanskrit sloka runs as:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , Atharva Veda, Book XII, Hymn 1.

, Atharva Veda, Book XII, Hymn 1.

30 UN (2015), n.9.

31 Swedish Delegation (1972), Statement by Prime Minister Olaf Palme in the Plenary Meeting of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, 06 June 1972, pp.3-4; quoted in Anna Sundstrom, pp. 180-181, n. 26.

32 Bharat H Desai, “Big ideas needed to envision environment safety,” The Tribune, 8 June 2022; Big ideas needed to envision environment safety: The Tribune India:

33 On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the UNFCCC, the Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa drew attention of the states’ parties that “Because despite all of our work, our memories and our successes, science makes one thing clear: nations are not currently on track to achieve their collective goals on climate change”; UNFCCC (2022), “UNFCCC 30th Anniversary - Tough Decisions Are Needed by All,” 9 May 2022; https://unfccc.int/news/unfccc-30th-anniversary-tough-decisions-are-needed-by-all

34 UN (2022), “Secretary-General’s remarks to Stockholm+50 international meeting”, Stockholm, Sweden, 02 June 2022; available at: Secretary-General’s remarks to Stockholm+50 international meeting [as delivered] | United Nations Secretary-General. Also see, UN (2022), “Rescue us from our environmental ‘mess’, UN chief urges Stockholm summit”, UN News

35 Ibid.

36 UN (2022), The Impact of the Stockholm Conference on the UN System: Reflections of 50 Years of Environmental Action, Environment Management Group, p.11; available at: Resources | Stockholm+50.

37 UN (2022), n. 34.

38 UN (1992), Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3–1 4 June 1992, vol. I, Resolutions Adopted by the Conference (United Nations publication, 1993), Resolution 1, Annex I

39 UN (2022), Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August–4 September 20 0 2, Chap. I, Resolution 1, Annex

40 UN (2012), “The Future We Want”, General Assembly resolution 66/288, Annex of 27 July 2012; UN Doc. A/66/288 of 11 September 2012; UN General Assembly - Resolutions

41 Bharat H. Desai (2023) and Bharat H Desai (2022), n. 18. Also see, Christina Borst (2022), “The Stockholm+50 Conference: What You Need to Know and Why it Matters”, UN Foundation Blogpost, 13 April 2022; The Stockholm+50 Conference: What You Need to Know and Why It Matters | unfoundation.org.

42 UN (2022), Statement by the Secretary-General at the conclusion of COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, 19 November 2022; Statement by the Secretary-General at the conclusion of COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh | United Nations Secretary-General; United Nations Secretary-General | United Nations Secretary-General

43 UN (2022), n. 34.

44 US Department of State (2019), “On the US Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement”, Press Statement of Secretary of State, Michael R. Pompeo, 4 November 2019; On the U.S. Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement - United States Department of State

45 US Depart of State (2021), “The United States Officially Rejoins the Paris Agreement”, Press Statement of Secretary of State, Antony J. Blinken, 19 February 2021; The United States Officially Rejoins the Paris Agreement - United States Department of State

46 UNFCCC (2015), Paris Agreement; ADOPTION OF THE PARIS AGREEMENT - Paris Agreement text English (unfccc.int)

47 Tirumurti, T.S. (2022), Backtracking on Climate Action by the Developed Countries: Some Reflections of a Negotiator”, Environmental Policy and Law 52, 5-6 (2022). Also see, “Backsliding on climate action”, The Hindu, 26 July 2022; The West is backsliding on climate action - The Hindu

48 IPCC (2022), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; available at: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability | Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (ipcc.ch)

49 UNEP (2022), Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window, Nairobi, available at: https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2022

50 Bharat H. Desai (2023), “Global Climate Change as A Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call For The Decision-Makers”, Global Diplomacy, 13 February 2013; available at: Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-makers — Green Diplomacy; Bharat H Desai (2022), “The Climate Change Conundrum”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no. 5-6, pp. 327-328, 2022; available at: The Climate Change Conundrum - IOS Press

51 Bharat H. Desai and Moumita Mandal (2022), “The Cost of Climate Change Heightened Sexual and Gender-based Violence: A Challenge for International Law”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol.52, no.5-6, 2022, pp.413-427; available at: https://content.iospress.com/articles/environmental-policy-and-law/epl219049(accessed on 05 February 2023)

52 IISD (2022), “Summary of Stockholm+50”, Earth Negotiations Bulletin, vol.13, no.14, 6 June 2022, p.10

53 Stockholm+50 (2022), “Programme”; https://www.stockholm50.global/events/programme

54 Ibid.

55 Donella H Meadows et al. (1972), p.5, n.5.

56 For a detailed ideational work enshrined in 22 chapters, released on 03 June 2022 at the time of the 2022 Stockholm+50 Conference see, Bharat H Desai, Ed. (2022), Envisioning Our Environmental Future: Stockholm+50 and Beyond(Amsterdam: IOS Press); available at: Envisioning Our Environmental Future | IOS Press

57 UN (2022), Stockholm+50: Summary of Stakeholders Contributions to Stockholm+50, Doc. A/CONF.238/INF/3 of 2 August 2022; available at: A/CONF.238/INF/3 (undocs.org). Also see Stockholm+50 (2022), Synthesis Report of the Five Regional Multi-Stakeholders Consultations for the Stockholm+50, April/May 2022; available at: Resources | Stockholm+50

58 Bharat H. Desai (2010, 2013), Multilateral Environmental Agreements: Legal Status of the Secretariats (New York: Cambridge University Press); Multilateral environmental agreements legal status secretariats | Environmental law | Cambridge University Press; Also see UNEP, “Global Multilateral Environmental Agreements,”< https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/oceans-seas/what-we-do/working-regional-seas/partners/global-multilateral

59 ECOSOC (1968), Resolution 1346 (XLV), 30 July 1968. of 30 July 1968.

60 UN (1968), General Assembly resolution 2398 (XXIII), “Problems of the human environment”, 3 December 1968; Problems of the human environment (un.org)

61 UN (1992), United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992; United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992 | United Nations

62 UN (2002), World Summit on Sustainable Development, 26 August-4 September 2002, Johannesburg, World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg 2002 | United Nations

63 UN (2012), United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20); United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio+20.:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. At this 2012 UNCSD, the UN Member States decided to launch a process to develop a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which would build upon the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs 2000-2015) and converge with the post-2015 development agenda. The Conference also adopted ground-breaking guidelines on green economy policies. The Governments also agreed to strengthen the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) on several fronts with action to be taken during the 67th session of the General Assembly.

64 Stockholm+50 (2022), n.1. The international meeting featured four plenary sessions in which leaders made calls for bold environmental action to accelerate the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals.

65 UN (2015), n. 9.

66 Bharat H Desai (1992), n. 10, p.593.

67 Bharat H Desai (2022), “Stockholm+50 and Beyond: Envisioning Our Environmental Future,” SIS Blog Post, 7 June 2022; https://sisblogjnu.wixsite.com/website/post/blog-exclusive-stockholm-50-and-beyond-envisioning-our-environmental-future

68 UN (2022), n. 34.

69 Bharat H Desai, Ed. (2022), n. 56.

70 Bharat H Desai (2021), Our Earth Matters:Pathways to a Better Common Environmental Future(Amsterdam: IOS Press):Our Earth Matters | IOS Press

71 UN (2020), “In Focus: The 75th session of the UN General Assembly”, 15 September 2020; https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/2020/09/unga75/

72 Bharat H Desai (2020), “Our planet needs trusteeship to meet challenges”, The Tribune, 02 December 2020; Our planet needs trusteeship to meet challenges: The Tribune India

73 PM India (2020), “15th G20 Leaders’ Summit,” 21 November 2020; 15th G20 Leaders’ Summit | Prime Minister of India (pmindia.gov.in)

74 UN (2021), UNSGSA 2021 Annual Report to the Secretary-General; available at: UNSGSA-Annual-Report-2021.pdf

75 Bharat H Desai (2000), “Revitalizing International Environmental Institutions: The UN Task force Report and beyond”, Indian Journal of International Law, vol.40, no.3, pp.455-504 at 455; available at: (7) (PDF) Revitalizing international environmental institutions: The UN Task Force Report and beyond (researchgate.net)

76 Ibid.

77 UN (2021), “Modalities for Summit of the Future”, General Assembly resolution 76/307 of 8 September 2022; Modalities for the Summit of the Future: (un.org)

78 UN (1948), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted through the General Assembly resolution (entitled International Bill of Human Rights) 217 (III) A of 10 December 1948; available at: Universal Declaration of Human Rights | United Nations

79 UN (1972), n.3

80 For example, Obed Y Asamoah (1966), The Legal Significance of the Declarations of the General Assembly of the United Nations (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff), p.30.

81 UN (2022), Stockholm+50: Organizational and Procedural Matters; UN Doc. A/CONF.238/2, 27 April 2022; available at: Documents | Stockholm+50

82 Ibid, paragraphs 3 and 4.

83 Stockholm+50 (2022), Presidents’ Final Remarks to Plenary: Key recommendations for accelerating action towards a healthy planet for the prosperity of all, paragraphs 8 and 10; available at: Presidents’ Final Remarks to Plenary: Key recommendations for accelerating action towards a healthy planet for the prosperity of all | Stockholm+50

84 UN (2022), “Ministerial declaration of the United Nations Environment Assembly of the United Nations Environment Programme at its fifth session Note by the Secretariat”; UN Doc. A/CONF.238/7, 14 April 2022. The United Nations Environment Assembly UNEA) of the UNEP, in its ministerial declaration adopted on 2 March 2022 at its resumed fifth session, requested the Executive Director of the UNEP, in her capacity as Secretary-General of the international meeting entitled “Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all –our responsibility, our opportunity”, to forward the declaration as the input of the Assembly to the international meeting. The declaration was issued under the symbol UNEP/EA.5/HLS.1.

85 UNEP (2022), Stockholm+50: Reflecting on global environmentalism, Speech delivered by Inger Andersen: Preparatory meeting for the Stockholm+50 International Meeting: A healthy planet for the prosperity of all –our responsibility, our opportunity, Location: New York, 28 March 2022; available at: Stockholm+50: Reflecting on global environmentalism (unep.org)

86 UN (2022), n. 34.

87 UN (2023), Turn words into action to get world back on track for 2030 goals, UN Secretary-General address to the General Assembly, 13 February 2023; available at: Turn words into action to get world back on track for 2030 goals | UN News

88 Stockholm+50 (2022), n. 83.

89 For a detailed scholarly exposition on this see, Bharat H Desai (2004), Institutionalizing International Environmental Law (Ardsley, New York: Transnational Publishers), Part II, Chapters 3, 4 and 5.

90 UN (2022), “Modalities for the Summit of the Future”, General Assembly resolution 76/307 of 8 September 2022; A/RES/76/307, 12 September 2022; N2258747.pdf (un.org)

91 For a detailed analysis and case for elevating climate change action as a planetary concern see, Bharat H. Desai (2022), “Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern”, Environmental Policy and Law 52, 5-6 (2022), pp.331-347. Also see Bharat H Desai (2023), “Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-up Call for the Decision-makers”, Green Diplomacy

92 Bharat H. Desai (2014), International Environmental Governance: Towards UNEPO? (Boston: Brill Nijhoff); “The Quest for a United Nations Specialized Agency for the Environment”, The Roundtable (Routledge, London), vol. 101, no. 2, 2012, pp.167-179; The Quest for a United Nations Specialised Agency for the Environment: The Round Table: Vol 101, No 2 (tandfonline.com); “UNEP: A Global Environmental Authority?” Environmental Policy and Law, vol.36, no.3-4, 2006, pp.137-157; “Revitalizing International Environmental Institutions: The UN Task Force Report and Beyond”, Indian Journal of International Law, vol.40, no.3, 2000, pp.455-504.

93 Bharat H Desai (2022), “Repurposed UN Trusteeship Council for the Future” in Bharat H Desai (Ed.), Envisioning Environmental Future: Stockholm+50 and beyond (IOS Press: Amsterdam, Berlin, Washington DC, 2022), pp.53-65. Also see, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no. 3-4, 52 (2022) 223–235; available at: epl219039 (iospress.com); “On the Revival of the UN Trusteeship Council with a New Mandate for the Environment and the Global Commons,” Environmental Policy and Law 48(6):333-344; https://content.iospress.com/articles/environmental-policy-and-law/epl180098; “The Repurposed UN Trusteeship Council for the Future”, Green Diplomacy, 25 January 2023; https://www.greendiplomacy.org/article/the-repurposed-un-trusteeship-council-for-the-future/

94 UN (2021), Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary-General (New York: UN); Secretary-General’s report on “Our Common Agenda” (un.org)

95 UN (2022), n. 1

96 UN (2022), “Stockholm+50 issues call for urgent environmental and economic transformation,” https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/06/1119732

97 UN (2022), UN News, 02 June, n. 34.

98 Bharat H. Desai, Ed. (2021), Our Earth Matters:Pathways to a Better Common Environmental Future(Amsterdam: IOS Press):Our Earth Matters | IOS Press; Bharat H. Desai, Ed. (2022), Envisioning Our Environmental Future: Stockholm+50 and Beyond(Amsterdam: IOS Press):Envisioning Our Environmental Future | IOS Press; Bharat H Desai, Ed. (2023), International Environmental Law: UNFCCC@30 and Beyond (Amsterdam: IOS Press; forthcoming).

99 Stockholm Environment Institute (2022), “Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future,” Stockholm Environment Institute, 18 May 2022; Stockholm+50: unlocking a better future - SEI. As per this report: The ‘action gap’ is significant. We do not have a gap in policies and aspirations, rather in actions. Since 1972, only around one-tenth of the hundreds of global environment and sustainable development targets agreed by countries have been achieved or seen significant progress; it is not enough. The knowledge and the means of solving our problems are known and available; implementation is missing.”

100 UN (2022), “Modalities for the Summit of the Future”, General Assembly resolution 76/307 of 8 September 2022; A/RES/76/307, 12 September 2022; N2258747.pdf (un.org)

101 Bharat H Desai (2022), “The Climate Change Conundrum”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 52, no. 5-6, pp. 327-328; https://content.iospress.com/articles/environmental-policy-and-law/epl219054

102 Bharat H. Desai (2022), “The Stockholm Moment”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol.52, no.3-4, pp.171-172; The Stockholm Moment - IOS Press (accessed on 18 February 2023).