Space, story, and solidarity: Designing a Black MLIS student organization amidst crisis and tumult

Abstract

According to LIS research, the U.S. library and information science field reflects more than 135 years of white racialized, monocultural pedagogy. Critical race theory helps us understand why Blacks remain on the margins of the LIS profession. Armed with critical racial knowledge, the Black Caucus of the American Library Association embarked on a three-year project to assert Black culture in a profession that has historically overpowered other ways of knowing. This article chronicles how BCALA leaders gleaned from Black-centered pedagogical traditions, data on Black MLIS students’ needs, and the critical race theory tenet of counterstorytelling to scaffold a national, online Black MLIS student organization that exists autonomously from mainstream U.S. LIS programs.

Ongoing racist violence, health disparities, and political demagoguery substantiate the premise upon which critical race theory (CRT) rests: in the U.S., white racial dominance manifests throughout legal, political, and other public systems (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017; Crenshaw, 2019). The U.S. LIS field is enveloped in this reality, what with mounting strategic anti-CRT and/or anti-Black racist censorship efforts. Attempts to suppress non-dominant ways of knowing have long implicated the LIS field. The call to contribute to a special issue on critical race theory motivated us to build on our (Ndumu & Walker, 2021) Education for Information Black Lives Matter special issue article on “Adopting an HBCU-inspired framework for Black educational success in U.S. LIS education”. Black-centered, HBCU11 – derived knowledge systems can advance library and information science education. Critical race theory helps us understand why Black counterstories are necessary for redressing the U.S. library profession’s implicit and explicit whiteness.

In this article, we will explain how Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA) leaders gleaned from Black-centered pedagogical traditions, data on Black MLIS students’ needs, and the critical race theory concept of counterstorytelling to scaffold a national, online Black MLIS student organization. Founded in 1970 by Dr. E.J. Josey, Effie Lee Morris and other African American leaders, BCALA is an independent nonprofit that advocates for the development, promotion, and improvement of library services and resources for the nation’s African American or Black communities. Like so many African American endeavors, BCALA was born of frustration and necessity. As far back as the 1930s, Black librarians would gather in hotel rooms at ALA Conferences to commiserate about the injustices and lack of opportunities throughout the library profession. Black library leaders decided that ALA was not serving the needs of Black library professionals (BCALA, 2022). BCALA’s 50th anniversary milestone in 2020 presented an opportunity to gauge ways to connect with emerging librarians. In what follows, we describe the rationale and process leading to the Breaking Barriers grant project designed to launch the iBlackCaucus student organization.

1.Premise

Libraries are testaments of lived experience. In the U.S., Blacks’ educational aspirations have historically been devalued. Few domains demonstrate a white racial skew as profoundly as library and information science. This is to say, a white mainstream monocultural standard encompasses library heritage and continues to uphold white racialized ideals and interests. Racist LIS educational exclusion is well-documented. Blacks are overlooked on account of power imbalances that rely on anti-Black racism and all of its attendant social harms: perceptions of Black intellectual inferiority; the exclusion of Blacks from higher education; the resistance to Black advancement within public-facing institutions; and, in LIS, career gatekeeping. Patin (2020) writes of epistemic violence that silences topics by and about minoritized, especially Black information scholars; Ndumu and Chancellor (2021) write about the strategic icing out of four library schools at historically Black colleges and universities; Johnson (2019), Walker (2015; 2017; 2020), and Gray (2020) write about the defiant measures Blacks took to build their own libraries and archives; Evans (2021) reflects on W.E.B. DuBois’ advocacy on behalf of New York City public librarians; Cooke (2017) recounts the slights that African American Carnegie Scholars endured while matriculating through the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign’s library school. Cooke later edited a 2019 Journal of Education for Library and Information Science Education special series on the microaggressions that Black and other racially minoritized library faculty regularly face. BCALA also published the latest (2022) iteration of the Black Librarians in America series. These publications represent a sliver of works built on the contributions of early Black library pioneers. Black-centered knowledge flies in the face of white normativity in LIS.

It stands to reason, then, that Black students enrolled in master’s LIS programs (who, axiomatically, are afforded even less agency given academia’s rankist nature) face similar underestimation and indignities. Such oppression has culminated in librarianship being out of touch or access for Blacks. Once white racialized elitism is made clear, librarianship’s assimilative, civilizing agenda within the LIS field becomes discernible. Hatchcock’s (2015) description of “white librarianship in Blackface” critiques white racial assimilation. Whether explicitly or unconsciously, people of color know that “if one is not a member of the [U.S.] ruling class, epistemic supremacy creates an ontological crisis that forces them to either assimilate … or go in search of liberatory frameworks” (Morales & Williams, 2020, p. 78). While whites in power historically regarded library settings and work as mechanisms for cultural remediation, their Black counterparts and BCALA, specifically, have approached libraries as vehicles for emancipation. In Fugitive Pedagogy: Dr. Carter G. Woodson and the legacy of Black education Jarvis Givens describes Dr. Woodson’s clandestine, radical Black-centered education that insists on Black humanity. Givens revises the depiction of “Black teachers as mere accommodationists” by asserting that:

Black people’s political clarity meant they understood their teaching and learning to be perpetually taking place under persecution, even as they created learning experiences of joy and empowerment (p. 10).

Given’s premise is transferable to LIS. Black librarianship presents a rebuttal to socioracial indoctrination that positions white society as the authority.

Critical race theory provides constructs to grasp the power structures at play in U.S. LIS. Among the earliest scholars to engage with critical race theory in the LIS context, Dunbar argued that the theory’s relevance to the LIS field lies in its reframing of information flows – that is, “every aspect of information including its form, use, structure, and infrastructure can be analyzed in order to understand the ways in which it reflects and represents the beliefs, values, practices, and politics of our society” (p. x). A long line of LIS scholarship (including but not limited to Honma, 2005; Furner, 2007; Brook et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2018; Hall, 2012; Hudson, 2017; Johnson, 2016; Kumasi, 2012; Leckie et al., 2010; Walker, 2015) subsequently unpacked how a racial caste system makes whiteness a political privilege, social power, and economic property.

The post-2020 global unrest inspired other critical race theoretical LIS works, notably Stauffer’s (2020) critique of LIS’s propensity toward “educating for whiteness” in which they applied a revisionist historical and critical race theoretical methodological lens to LIS research along with Leung and Lopez-McKnight’s edited, open access book on “Knowledge justice: Disrupting LIS through critical race theory.” In it, forty-five writers confront LIS norms by critiquing social constructions of race. Addressing the U.S. LIS field’s white racialization requires opposing narratives. Delegado, an initial advancer of counterstorytelling as a social justice tool, suggests that “oppressed groups have known instinctively that stories are an essential tool to their own survival and liberation. Members of out-groups can use stories in two basic ways: first, as means of psychic self-preservation, and second, as means of lessening their own subordination” (1989; p. 2436). More closely to LIS, Dunbar (whose dissertation committee included another leading counterstorytelling theorist, Daniel G. Solorzano) submits that storytelling entails subversive chronicles that both cast doubt on information norms and expose information bureaucracies (2008, p. 25). From a pedagogical standpoint, counterstorytelling can inject non-white, humanizing, and experiential knowledge (Walker, 2015; Cooke, 2016). Counterstorytelling is neither new nor exceptional to the Black librarian experience. For more than a century, Black librarians cultivated their own paths and stories to defiantly enter and persist in a domain that was never intended for people of color. Even when opportunities in libraries and librarianship were extended to people of color, such concessions principally materialized to deepen dominant society’s power. This “interest convergence,” as Derrick Bell (1980) coined it, relies on the vested interests of White elites. It follows, then, that Black social progress has relied on buy-in from the mainstream white political and economic establishment. The same goes for the library and information science field which has depended especially on white corporate industrial investment and approval.

Counterstories, on the other hand, call white endorsement into question. It eschews permission; it seeks no invitation. This very premise is what inspired the need for a by-us, for-us BCALA-sponsored student organization. We are especially drawn to Honma’s (2021) summation that “counterstorytelling unearths the contradictions inherent within American liberal democracy as a racial onto-epistemological project that has worked as much to exclude as it has to include” (p. 46). We fully understand that LIS educators and leaders would do well to combine anti-racist, evidence-based context to establish socially empowering partnerships, pathways, and curricula (Ndumu & Chancellor, 2021). Hence, the BCALA Breaking Barriers team set out to launch the iBlackCaucus student organization by combining counterstorytelling, an HBCU-inspired framework, and comprehensive data on Black MLIS student realities.

2.Space: understanding Black MLIS students’ needs

Designing a nationwide space uniquely for Black MLIS students calls for knowing their needs. The Breaking Barriers team employed a triangulated approach by analyzing varied data on Black MLIS students’ representation and experiences. First, the Association of LIS Education’s (ALISE) 2018 Statistical Report revealed that out of 8,455 MLIS students, 725 (8.5%) identified as Black. Next, the team turned to BCALA’s membership records and learned that of those 725 Black MLIS students across North America, only 90 (8%) were BCALA members. Next, the Breaking Barriers team analyzed findings from a 2018 BCALA comprehensive membership survey. Of the 248 survey respondents, just 12.93% (

Further, the Breaking Barriers team gathered a wider response by surveying Black/MLIS students enrolled in ALA-accredited MLIS (or equivalent) programs. One hundred twenty-seven Black (

Regarding their social experiences, respondents overwhelmingly agreed that non-instructional support enhances librarian careers. Notwithstanding, most indicated that they lacked or were unaware of opportunities for non-instructional student engagement (i.e., meet-ups, webinars, socials) at the MLIS programs that they were enrolled in (Table 2). A large portion of respondents did not participate in student organizations at their institutions, nor were there groups for students of color such as BCALA and REFORMA (the National Association to Promote LIS to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking). The majority of respondents (

Many respondents expressed that MLIS programs foster positive and rewarding environments (

As a final step, the Breaking Barriers team gleaned from LIS literature to grasp the characteristics of meaningful MLIS student engagement. The team reviewed LIS publications on effective LIS student support with an eye for indicators of Black student success, as put forward in Gasman and Arroyo’s (2014) HBCU-inspired framework. The collective effectiveness of HBCU institutions lies in their supportive environment – or, “positive power motives” and feelings of safety and recognition (p. 64); flexible entry points – or, educational visibility, accessibility, and affordability;

Table 1

Black MLIS student involvement

| Non-instructional support or enrichment is important to becoming a librarian. ( | There are opportunities for non-instructional student engagement (i.e., meet-ups webinars, | ||||

| socials) at the MLIS | |||||

| program that I am | |||||

| enrolled in. | |||||

| ( | I participate in various student organizations (i.e., ALA, SLA) at the MLIS program that | ||||

| I am enrolled in. | |||||

| ( | There are organizations for students of color (i.e., REFORMA, APALA, BCALA) at the MLIS | ||||

| program that I am | |||||

| enrolled in. | |||||

| ( | I engage with other librarians and MLIS students on social media or digital platforms. ( | ||||

| True | 92 | 40 | 37 | 33 | 68 |

| False | 1 | 53 | 57 | 26 | 26 |

| Unsure | 7 | 8 | 6 | 42 | 7 |

Table 2

Black MLIS student learning experiences

| The MLIS program and courses foster a positive and rewarding environment. | |||||

| ( | I feel safe and accepted in the MLIS program that I attend, and can fully express my | ||||

| viewpoints in courses. | |||||

| ( | There is racial representation and inclusion among the faculty and staff at the program that I attend. | ||||

| ( | My MLIS courses adequately address issues pertaining to race, ethnicity, and social equality within the curriculum. | ||||

| ( | In my MLIS courses, I learn about organizations for librarians of color (i.e., the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, REFORMA). ( | ||||

| True | 69 | 57 | 36 | 49 | 31 |

| False | 8 | 14 | 43 | 25 | 47 |

| Unsure | 23 | 29 | 22 | 25 | 23 |

broad, iterative interpretation of student achievement rooted in culturally relevant pedagogy, identity formation, and values cultivation (p. 68); and a holistic view of career success that makes room for social consciousness and change-oriented leadership (p. 70).

Based on available LIS scholarship, a virtual cohort approach appeared promising and viable for engaging with Black LIS students. An interactive, innovative online platform would align with current LIS educational norms. As Robinson and Hullinger (2008) put it, “there is no change in higher education more sweeping than the transformation brought about by the advent of the Internet.” (p. 62) The shift in LIS education from on-campus to distance-learning delivery means that student involvement must also change (Dare et al., 2005). For instance, Al-Daihani’s study (2009) on social media use among University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee MLIS students showed that social networking is favorable for student professional growth. Similarly, Dow (2008) found that social presence and interactivity are predictors of LIS student satisfaction. Examples of technology-enhanced LIS student organizations include the University of Maryland’s iDiversity student group (Jardine & Zerhusen, 2015). In light of online education’s ubiquity within LIS graduate education, new librarians seek camaraderie online, as reflected by virtual groups such as Libraries We Here, Hack Library School, WoC

Extracurricular socialization has been found to support librarian professionalization. In their study of LIS student experiences and motivations, Caidi and Dali (2017) suggest that “people-related factors” such as “sense of community and inclusivity” greatly influenced LIS students’ professional outcomes. Creating “robust networks of educational resources and technological platforms” is one of their recommendations, underscoring the centrality of the Internet. Indeed, these connections can grant solidarity, cultural identity, and resilience. Students flourish when afforded with developmental activities such as mentorship and group dialogue.

Yet, the presence of online extracurricular organizations within LIS schools is fleeting. Online LIS education has resulted in fewer affinity student groups across MLIS programs – for example, student chapters of BCALA and cognate organizations that can enhance students’ professional growth and involvement. Educational isolation among LIS graduate students necessitates strident investment in their social and professional growth. A sense of belonging is vital when thinking about racially underrepresented LIS graduate students, particularly in light of growing knowledge of how librarians of color experience low morale (Kendrick & Damasco, 2019) and microaggressions (Arroyo-Ramirez et al., 2018; Sweeney & Cooke, 2018).

BCALA saw the potential for a virtual student organization to bolster connections beyond graduate school, ones that boost racially relevant camaraderie and LIS program-independent recruitment. Inattention to recruitment negates efforts to foster a supportive space for Black MLIS students. Stated differently, BCALA’s outreach to students must be cyclically sustained through both community-building and fervent promotion. This essential work cannot be left to LIS programs alone.

3.Story: designing a Black-centered MLIS student organization

Armed with multifaceted evidence, the BCALA Breaking Barriers team set out to create a dedicated, intentional setting for current and potential Black MLIS students. To amend Black MLIS students’ white racialized educational experiences, BCALA leaders envisioned a new online student engagement model. Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services supported the Breaking Barriers National Forum to ideate and launch a BCALA-sponsored online, Black student organization that operates independently from MLIS programs.

After the initial environmental scan, the team set out to plan and execute the Breaking Barrier National Forum, a community-driven, participatory pre-conference dialogue to establish iBlackCaucus. The forum’s intended outcome entailed creating the iBlackCaucus student organization’s structure (e.g., formal, stand-alone group with a governing committee or an informal, dialogic and periodic group) and recruitment material. The forum was originally planned as a pre-conference workshop at the 2020 National Conference for African American Librarians (NCAAL) that was postponed as a result of the COVID-19. Coincidentally, the NCAAL theme rested on the principle of Sankofa, or “go back and get” (san – to return; ko – to go; fa – to fetch, to seek and take) in the Kan Twi and Fante languages of Ghana. In the same vein, the Breaking Barriers project sought to present a counterstory, to again evoke critical race theory, and reclaim Black librarianship from a marginal place to the forefront of LIS education.

Selected students received conference sponsorships through the Breaking Barriers grant project. In response to gradually improved public health conditions, the Breaking Barriers forum was eventually offered as a two-part initiative starting with a virtual symposium followed by an in-person meeting. Both events centered Black MLIS students’ stories.

3.1Breaking Barriers virtual symposium

The virtual symposium allowed the Breaking Barriers team to execute the types of activities that might inject community-building and critical racial thought within Black MLIS students’ educational experiences. Throughout the Breaking Barriers project, the team prioritized experience and meaning rather than outcome and function. Intentionality undergirded this work, and care was put into each element.

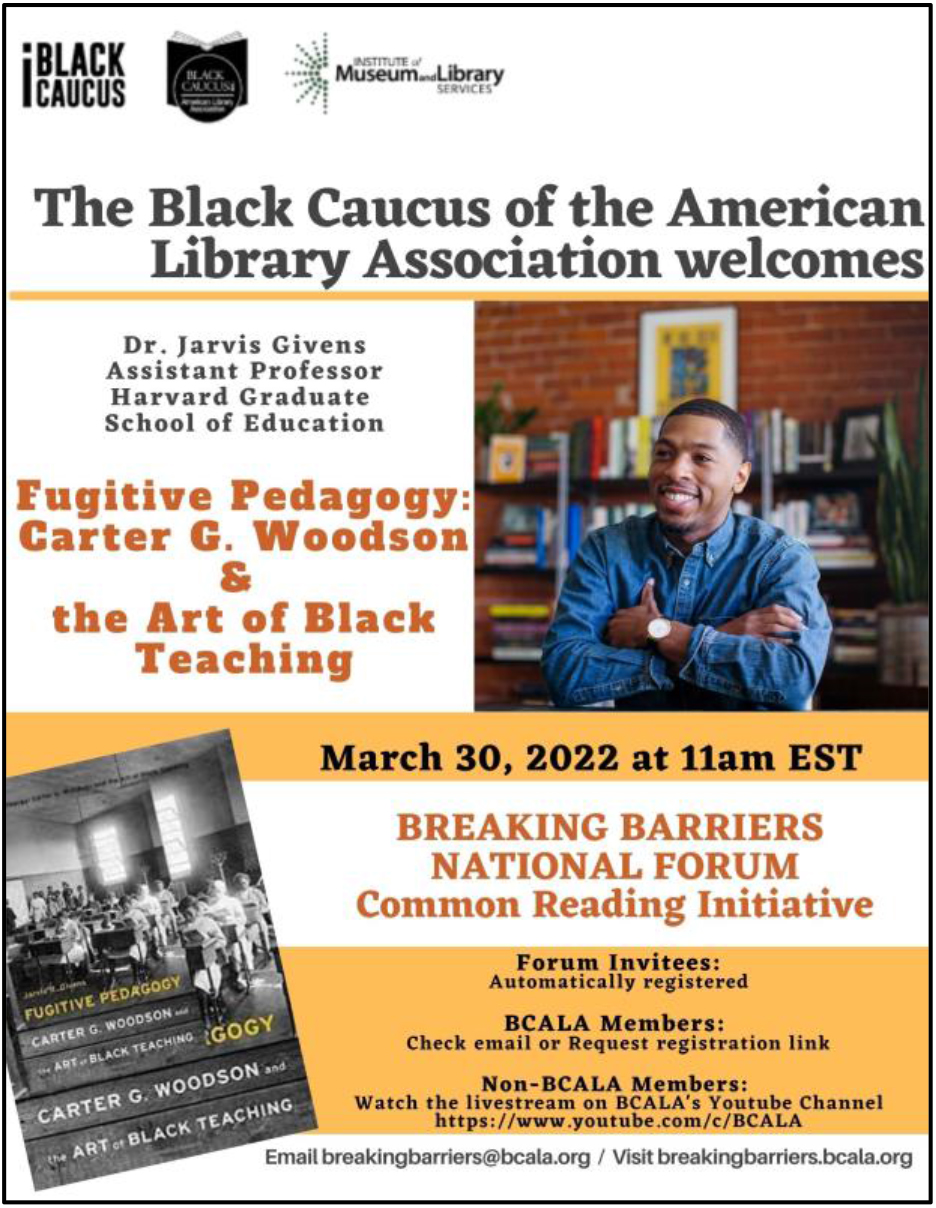

On March 30, 2022, forty students participated in a day-long virtual working meeting in which they co-created iBlackCaucus. Figures 1 and 2 show the Breaking Barriers project website and virtual symposium workbook. The symposium opened with introductions followed by breakout meet-and-greet sessions led by the Breaking Barriers Advisory Committee. As explained earlier, the team was stretched by Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s example of persistent anti-racist teaching. Dr. Jarvis Givens accepted the Breaking Barrier Team’s invitation to deliver a keynote address on Dr. Woodson’s transgressive educational agenda as presented in Fugitive Pedagogy: Dr. Carter G. Woodson and the legacy of Black education (Fig. 3) Givens’ notion of fugitive education challenged symposium attendees (and, since it was broadcasted live on Youtube, BCALA members and allies) to consider the persistent tactics by which African American teachers customized their teaching. Breaking Barriers symposium attendees were asked to consider how a BCALA student organization can insert Black interests and ideology into white-aggrandizing library settings. Givens’ talk set the tone for the subsequent brainstorming session. Attendees were asked to apply Givens’ points on Woodson’s fugitive pedagogical approach to rethinking LIS education.

Figure 1.

BCALA Breaking Barriers website.

Figure 2.

BCALA Breaking Barriers virtual symposium workbook.

Figure 3.

Dr. Jarvis Givens keynote speech flyer.

Next, Breaking Barriers attendees participated in an ideation workshop led by a Breaking Barriers team followed by an LIS equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) consultant. In the first activity, participants were asked to draw their information worlds (Jaeger & Burnett, 2010) as Black MLIS students. To do so, participants utilized Jenna Hartel’s (2014) iSquares (information squares) technique to portray their MLIS educational journeys. The iSquares technique is an LIS adaptation of the popular draw-and-write technique. In our application, participants used autodraw.com rather than a 4-by-4 inch paper to respond to the questions: “What is the dominant message throughout my MLIS journey? and “Does my MLIS program reflect a white racial metanarrative?” Participants then captured and emailed their image to the Breaking Barriers team.

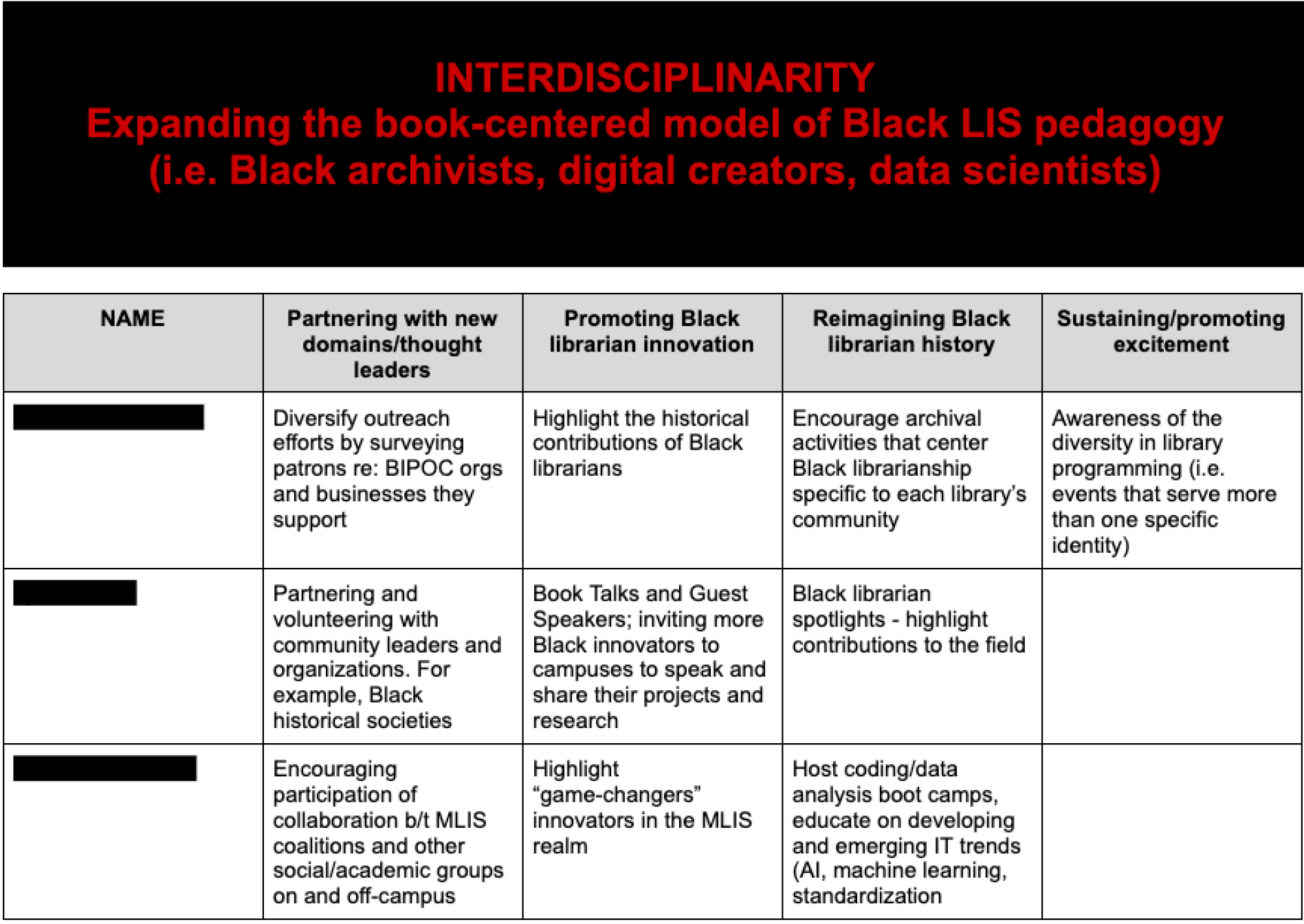

The second activity involved brainstorming whereby students synchronously added their thoughts to a shared document. This time, they answered the prompt: “How can Black MLIS students leverage their experiences to address information inequities and exclusion?” and “How can Black/MLIS students continue to thrive and grow in Library & Information Science programs?” Students weighed in on several areas of concern raised by critical race theoretical and/or LIS scholarship: relevance, agency, transformation, intersectionality, and interdisciplinarity. The themes elicited detailed participant responses on MLIS pedagogical realism for Black MLIS students; how Black MLIS students can assert their expertise into the learning process; methods of building and strengthening radical Black MLIS recruitment; the need to recognize the range of Black students’ backgrounds and expertise; and tactics for expanding beyond the book-centered model of Black-centered LIS pedagogy.

Figure 4.

Sample ideation session – activity 2.

The symposium transitioned to a panel discussion featuring Trevor Dawes (assistant director at the University of Delaware, a research-intensive university, as well as past president of the Association for College & Research Libraries), Dr. Amelia Gibson (then associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who theorized the concept of information marginalization), and Shannon Bland (Charles County, Maryland library system branch manager and founder of the Black Librarians Network, an online and social media platform to foster Black librarian solidarity). The panel shared accounts and guidance for thriving in various LIS spheres. The Breaking Barriers symposium concluded with a wellness workshop and closing remarks.

3.2Breaking Barriers workshop at the 2022 ALA Annual Conference

The Breaking Barriers project also supported participant registrations, accommodations, and travel to attend the 2022 ALA Annual Conference in Washington, D.C. This in-person workshop allowed students the rare opportunity to meet face-to-face with LIS students from across the country and, in doing so, foster an offline sense of belonging. On June 26, 2022, Break Barriers participants engaged in the hour-long “Envisioning iBlackCaucus: An interactive, working session to strengthen MLIS student engagement.” The purpose of this second event, structured as a design thinking session, was to address the questions, “What is the best structure for a virtual Black/MLIS student organization independent of MLIS programs?” and “What types of infrastructure and support are necessary for sustaining a virtual Black/MLIS student organization that is independent of MLIS programs?” In contrast to the first session’s all-day dialogic and reflective in scope, this workshop was faster-paced, condensed, and design-oriented.

Through guided, interactive activities such as round-robin cardsorting and turn-and-talk discussions, attendees were invited to have a say in the iBlackCaucus student organization’s purpose, governance, and activities. The session was open to all BCALA members and approximately 50 people attended. The thirty-three MLIS students who received Breaking Barriers program sponsorships were invited to a post-workshop reception (that coincided with the Black Librarian in America book launch) followed by a semi-annual BCALA Membership Meeting.

3.3Findings

Themes from both the virtual symposium and in-person workshop revolved around the need for open, honest and democratic discussions (e.g., “willingness to have tough conversations,” “lack of input from folks you’re trying to serve”), a desire for lively social activities that contrasts the often formal, impersonal online graduate education (e.g., “not boring”, “not enough fun,” “no camaraderie so it feels like another job”) but does not strain members’ time and energy.

The Breaking Barriers program team recognizes that Black MLIS students bring with them tremendous vocational expertise since many worked in other sectors and earned other graduate degrees prior to pursuing LIS careers. Recognizing participants’ professional agency is yet another component of emancipatory and liberative education. When asked about successful LIS organizational models, participants noted easy, consistent but balanced communication and meetings; emotional support and psychological safety; clear mission and vision; and, of course, diversity and representation. Participants described unsuccessful organizational models as those that lack either strategy and purpose; trust, transparency, and respect for members’ privacy; or welcoming, warm environments, or adequate support and resources. When asked about factors that might prevent students from taking part in a virtual, national student group, participants primarily noted structural impediments such as time availability (e.g., “balancing work, grad school, and family”, “being stretched too thin”), inadequate support (e.g., “time release,” “supervisor buy-in”; “funding to attend events or join groups”); or simply too few opportunities for serendipitous, unforced bonding (e.g., “Support circles where students can simply vibe. Sometimes you need a space to just be able to talk safely, within your own community to build support.”) Making the most of one’s limited time was a recurring theme.

The iSquares virtual symposium activity suggests that Black MLIS students’ information worlds are multifaceted, dynamic, and, at times, overwhelming. Perhaps this is because of the expected knowledge and pressures of mastering new information tools and sources as emerging information professionals. This vocational expectation might explain why participants appear to seek in iBlackCaucus consistent, highly engaging, and meaningful educational opportunities. Desired structure and tools varied from monthly online sessions, shared living documents, and even recorded sessions offered through multiple platforms, whether web-conferencing, social media, and learning management systems. The virtual symposium elicited other high-level themes such as the need to better demonstrate the elasticity of the MLIS degree. For example, on the topic of interdisciplinarity one participant wrote:

“Not many people understand the potential and flexibility of the [MLIS] degree and the ‘nontraditional’ things that can be accomplished. The worth of the degree is often challenged. That comes with pushing through the stereotype as well.”

Feedback from the in-person workshop corroborated this point, and participants also opined on fostering pedagogical relevance through curricular co-ownership (e.g., “students have to be proactive. They must act as creators and agitators to bring up discussions related to their interests”) along with creating streamlined, ready-to-use support material (e.g., “strengthen national platform; one common space for students to seek resources and information”).

All told, customizing information-oriented research techniques such as iSquares and design thinking appeared to be effective in inviting students to envision what space and solidarity in MLIS education means to them, and what iBlackCaucus can be. In keeping with the spirit of reframing LIS, these methods were adapted to Black-centered ideation wherein attendees were welcomed to embrace and share their stories. We then put this collective narrative to action.

4.Solidarity: launching iBlackCaucus and fostering student support

4.1iBlackCaucus structure and scope

A thorough environmental scan coupled with carefully gleaned stakeholder input evinced that there’s promise in a cohort approach. This paper was finalized just before iBlackCaucus launched in the fall of 2022 during the 2022–2023 U.S. higher education academic calendar. In September, iBlackCaucus began to offer robust support for Black MLIS students through community-building, resource sharing, and racially relevant training – all components of HBCU-derived, Black-centered, and fugitive pedagogical praxis.

We honed in on two powerful takeaways: simplicity and impact. Throughout the four data-gathering exercises across two events, it was apparent that students call for lean commitments – ones that respect their time, labor, and know-how – that bring high yield in resources, connection, and belonging.

Content and resources

Based on copious feedback, iBlackCaucus offers monthly informal “Real Talk Brunch” talks. These low-stakes, casual 45-minute virtual meetups center on agreed-upon themes, virtual games, or common reading selections designed with Black MLIS students in mind. The sessions alternate between social and learning activities all intended to enrich students’ educational experiences beyond the LIS curricula. These student-led meetings provide opportunities for peer knowledge-sharing and community-building. Students also have access to a network channel along with abbreviated lessons and readings, which are described further on. These resources augment engagement and dialogue.

In addition to these casual meetings, iBlackCaucus hosts standardized semester training lectures on topics that affirm Black librarians’ racial professional, intellectual, and cultural distinctions. The speaker series consists of roundtable, panel, and keynote talks or teach-ins with experts on a range of topics that probe LIS professionalization and practice. Critical dialogue is, again, innate to BCALA, iBlackCaucus, and Black librarianship more broadly. As we note later, asynchronous discussions through a shared network application will enhance the iBlackCaucus Seminar and iBlackCaucus Real Talk Brunch conversations. Black LIS graduate students will be able to connect with peers who share similar interests, attend the same MLIS programs, and/or reside in the same region.

Finally, students will maintain a semester newsletter that curates LIS happenings, spotlights Black MLIS students across the country, and allows them to elaborate on their coursework such as papers and theses. The iBlackCaucus newsletter is yet another chance to center Black MLIS students’ stories. In addition to strengthening belonging and community, the iBlackCaucus newsletter grants Black MLIS students an opportunity to publish.

Governance and sustainability

Student involvement at the master’s level runs the risk of cessation due to the degree’s brevity (two years in the U.S. context). Distance or online education compounds this threat. Further still, iBlackCaucus is unique in that it has no formal affiliation with MLIS programs and/or iSchools. In other words, this endeavor is itself distant to LIS education, though, in some regards, its autonomy strengthens its overall prospects, we argue. iBlackCaucus is intended to eschew MLIS bureaucratic norms that impede Black interests.

To sustain iBlackCaucus and ensure that student representation remains a core part of BCALA’s operations, the student organization is steered by a Student Advisory Group composed of five to seven Black LIS graduate students who meet once per semester to plan events. The iBlackCaucus Advisory Committee is chaired by an iBlackCaucus Fellow. This de facto student organization’s president organizes and facilitates iBlackCaucus events for one year. The iBlackCaucus Fellow receives a $1500 stipend – or $500 per semester – plus free registration and accommodations to attend either the BCALA Leadership Institute and the National Conference for African American Librarians. The fellow also serves on the BCALA Executive Board, thereby ensuring that student interests are prioritized, and is mentored by two faculty advisors who guide iBlackCaucus. Fellows may reapply once. This structure is intended to create a leadership feeder pattern within BCALA – from student involvement to mid-level (committee, task force, or conference) chairing and eventual executive leadership within and beyond BCALA.

On a related note, a consistent point entailed strengthening organizational knowledge. Suggestions ranged from holding a student membership orientation, granting leadership development, or otherwise offering immersion in BCALA’s culture, infrastructure, and future. Hence, student members will receive a welcome video explaining the organization’s history, impact, governance, and opportunities. In iBlackCaucus’ inaugural year, all students who join BCALA will receive free memberships. Thereafter, student memberships will cost $10.

Platforms and tools

Students expressed interest in or familiarity with a range of online tools. To ensure that this student group is exclusive to BCALA student members, access to resources and opportunities is limited to those who join BCALA and thereby create a YourMembership (YM) account. The YM portal facilitates members’ access to all available resources. Student participants noted Zoom, Slack, and liveable documents as popular tools. Synchronous discussions are offered through Zoom, though some students cautioned against its overuse. Hence, iBlackCaucus programming is limited to the monthly Real Talks, semesterly iBlackCaucus Seminar talks, and quarterly Advisory Group meetings. To encourage informal, asynchronous connection, students can post questions, comments, or interesting news via a dedicated Slack channel.

Finally, beginning in January 2023, iBlackCaucus participants or BCALA grad student members will have access to Black-centered educational content through Google Classroom, a free and easily accessible learning management system. It will comprise learning modules on, for example, the popular, crowd-sourced “Black Excellence in LIS Syllabus”. The iBlackCaucus Classroom will also function as a repository of student newsletters along with photographs of past iBlackCaucus events. The latter are especially important for Black MLIS student recruitment, which we will touch on.

To summarize, BCALA’s YM portal is the gateway to iBlackCaucus resources: the Slack channel, iBlackCaucus Classroom, the monthly Real Talks, plus the semesterly guest talks and newsletters. The Breaking Barriers team was mindful of students’ request for substance without complexity. Our goal is to make iBlackCaucus content streamlined and available but not compulsive. iBlackCaucus participants will define their level of involvement.

4.2Student support

The Breaking Barriers virtual symposium and ALA workshop made it abundantly clear that MLIS students need assistance beyond a student organization. If Black students are to truly see themselves represented in LIS education, there must be deep support–the kind that reflects “Black American’s pursuit to enact humanizing and affirming practices of teaching and learning” (Givens, 2021, p. 11). The following represents other BCALA endeavors designed to strengthen Black MLIS student experiences beyond but adjacent to iBlackCaucus.

MLIS student of color commencement

Since Black MLIS students remain disproportionately underrepresented within U.S. LIS graduate programs, their successful matriculation is worthy of recognition. Beginning in 2020, the Black Librarians Network in partnership with BCALA organized an annual Black MLIS Students of Color Commencement held each spring. More than 100 students have taken part to date and Tracie D. Hall, ALA Executive Director, delivered the inaugural commencement address. Online graduation ceremonies grew in popularity during the pandemic and presented an opportunity to celebrate all students of color who persisted through LIS programs. The 2021 Virtual Commencement expanded to a partnership among several LIS organizations.

This event is significant considering, to echo Jarvis Givens’ description of pedagogical fugitivity, the ongoing need to rebut the “devaluing of Black educational strivings in this country’s history” which calls for “constant seeking of an outside to white supremacy that might be understood as Black freedom” (Givens, 2021, p. 11). Black MLIS educational joy and accomplishment is a counterstory that is worthy of celebration.

Figure 5.

MLIS student commencement flyer.

LEVEL UP mentorship program

Perhaps because of the remote and, at times, transactional scope of many MLIS programs, Black MLIS students reliably seek mentorship through the BCALA listserv. As described earlier, intergenerational, same-race mentorship contributes to identity formation, values cultivation, and a holistic view of career success; these indicators are key components of Black-centered, HBCU-derived pedagogy. The Breaking Barriers team worked together with the BCALA Professional Development Committee and Membership Committees to design a robust mentorship program that launched in March 2022. The outcomes were a mentorship program rooted in simplicity, heritage, and community. The BCALA LEVEL UP mentorship program (1) rejects Anglo-conformist librarian professionalization by affirming the Black experience in LIS (2) draws from a rich history of Black and Pan-African librarianship to foster career success, and (3) promotes Black librarian leadership through an easy, self-select, and mentee-driven mentorship structure.

Figure 6.

BCALA LEVEL UP mentorship program flyer.

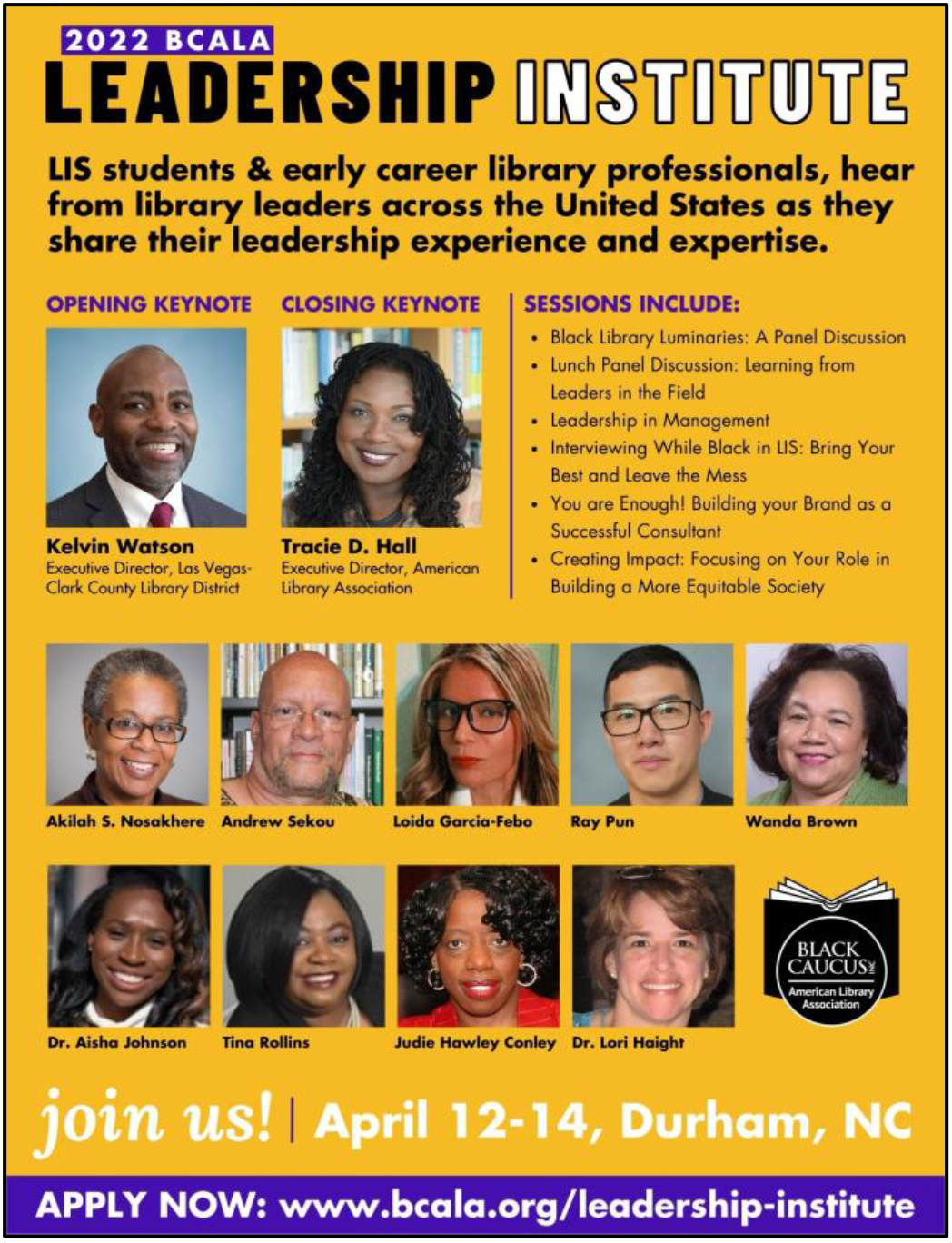

Leadership institute

Change-oriented leadership is germane to the Black librarian experience. Black librarian leadership directly counters historical racial subservience within the library sector. Despite nearly 100 years of African Americans being denied entry into white-dominated libraries, white library schools, and white library associations, African American library leaders such as Librarian of Congress Carla D. Hayden, ALA Executive Director Tracie D. Hall, and ALA Past President Wanda K. Brown have reached the highest levels of the profession. There remains a distinct vocational imperative to change the conditions and create pathways for future Black library leaders.

Given this, funding from the Breaking Barriers grant also supported an inaugural BCALA Leadership Institute. Fifty BCALA members took part in a day-and-a-half intensive training to increase their executive, communication, and decision-making skills. The leadership institute centered on Black librarian excellence and was hosted in Durham, North Carolina was sponsored in part by the historic North Carolina Central University, the only remaining HBCU-based library and information science program.

Figure 7.

BCALA leadership institute flyer.

HBCU open house

Finally, the BCALA Breaking Barriers team would be remiss not to revitalize the connection between HBCU undergraduate programs and MLIS education. At one point, there were five historically Black college/university library science programs (Ndumu & Chancellor, 2020). Varied archival evidence shows that American Library Association (ALA) bureaucrats strategically excluded most HBCU-based LIS programs, leaving just one at North Carolina Central University. Specifically, the ALA accreditation process was weaponized to enact uniquely but unjustifiably punitive measures upon HBCU-based LIS programs.

Black library leaders must reclaim the relationship between LIS and HBCUs. Through a partnership with HBCU librarians, BCALA will host an inaugural HBCU Student Open House in the spring 2023 to attract and orient HBCU undergraduate students majoring in humanities and information-oriented fields. The virtual half-day symposium will include panels, breakout sessions, and an MLIS Program Fair.

Additionally, the Breaking Barriers team is designing ready-to-use, freely downloadable promotional material to showcase LIS careers. Items include brochures, flyers, questionnaires, and short videos for one-on-one engagement with prospective MLIS students, particularly HBCU students and alumni. The material will also include iBlackCaucus newsletters and photographs. To date, there has been no centralized, open repository of Black MLIS recruitment material.

To summarize, the Breaking Barriers national project furthers BCALA’s commitment to fostering an LIS field that reflects the U.S.’s demographic plurality. Fashioning a positive LIS learning environment and supporting the next generation of Black librarians underscores BCALA’s mission and values. Considering the significant changes in U.S. LIS education – specifically, the physically and socially remote nature of delivery – it was necessary to create multifaceted support and infrastructure to sustain student engagement through and beyond iBlackCaucus. In executing the iBlackCaucus student organization, the Breaking Barriers project made certain to identify dynamic ways of creating meaningful systems, positive initial impressions, healthy environments, and flexible opportunities for career growth.

5.Conclusion

A Black student group that operates entirely independent of MLIS programs and is instead stewarded by the largest U.S. Black library association fits squarely in this thread of contrarian education, thus presenting a counterystory to the idea that information or knowledge work is reserved for the white status quo. This biased line of thinking kept Blacks out of libraries and librarianship for much of U.S. history. BCALA’s core message, which was again set ablaze during its 50th commemoration in the grim 2020 year, is that Blacks belong in libraries, librarianship, and U.S. society. If libraries nationwide are to function as community anchors and social equalizers, the visibility of librarians of color remains paramount. In addition to radically Black-centered library facilities, educational programs, organizations, and publications, there is a need for an autonomous, vibrant and national Black MLIS student organization.

iBlackCaucus can very well be a blueprint for Black student advocacy in the profession. iBlackCaucus is at its core is an act of resistance that grants attention to Black librarians whose stories have been overlooked. Research substantiates that minoritized people are more likely to work as library support staff and custodial workers than librarians. At last count, there were less than 15,000 MLIS-holding African Americans/Blacks throughout the U.S. despite there being 166,000 librarians overall (ALA Diversity Counts, 2017). This racial disparity within the LIS field is not by happenstance. Rather, it is the outcome of an imposed racial hierarchy enacted through information systems, including libraries. The lack of Black racial representation among LIS faculty, students, professionals, and association leaders results from whiteness as the library professional norm. We witness this same hegemony throughout the information sector broadly. White racialized dominance manifests in a bureaucratic, embattled publishing industry that lacks diverse books and authors; anti-Black software and algorithms; the mass criminalization and surveillance of Blacks through data violence; and the weaponization of state-sanctioned information-gathering such as the census. These conditions are not one-off occurrences but, on the contrary, symptoms of structural, deep-seated anti-Black racism throughout the U.S. information ecosystem. Combatting such inequities requires intention, care, and healing. For this very reason, iBlackCaucus affords space, story, and solidarity to a new generation of Black librarians.

Notes

1 In the U.S., historically Black colleges and universities are higher education institutions that were founded to educate African Americans prior to the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

References

[1] | Al-Daihani, S. ((2009) ). The knowledge of Web 2.0 by library and information science academics. Education for Information, 27: (1), 39-55. |

[2] | Arroyo, A.T., & Gasman, M. ((2014) ). An HBCU-based educational approach for Black college student success: Toward a framework with implications for all institutions. American Journal of Education, 121: (1), 57-85. |

[3] | Arroyo-Ramirez, E., Chou, R.L., Freedman, J., Fujita, S., & Orozco, C.M. ((2018) ). The reach of a long-arm stapler: Calling in microaggressions in the LIS field through zine work. Library Trends, 67: (1), 107-130. |

[4] | Bell, D.A., Jr. ((1980) ). Brown v. Board of Education and the interest-convergence dilemma. Harvard Law Review, 93: (3), 518-533. |

[5] | Black Caucus of the American Library Association (2022). Mission. Available at Crenshaw, K.W. ((2019) ). 3. Unmasking colorblindness in the Law: Lessons from the formation of Critical race theory. In Seeing Race Again, pp. 52-84. University of California Press. |

[6] | Brook, F., Ellenwood, D., & Lazzaro, A.E. ((2015) ). In pursuit of antiracist social justice: Denaturalizing whiteness in the academic library. Library Trends, 64: (2), 246-284. |

[7] | Brown, J., Ferretti, J.A., Leung, S., & Méndez-Brady, M. ((2018) ). We here: Speaking our truth. Library Trends, 67: (1), 163-181. |

[8] | Dali, K., & Caidi, N. ((2017) ). Diversity by design. The Library Quarterly, 87: (2), 88-98. |

[9] | Cooke, N.A. ((2017) ). The GSLIS Carnegie Scholars: Guests in someone’s house. Libraries: Culture, History, and Society, 1: (1), 46-71. |

[10] | Crenshaw, K.W. ((2019) ). Unmasking colorblindness in the Law: Lessons from the formation of Critical race theory. In Seeing Race Again, pp. 52-84. University of California Press. |

[11] | Dare, I.A., Zapata, L.P., Thomas, A.G. ((2005) ). Assessing the needs of distance learners: A student affairs perspective. New Directions for Student Services, 2005: , 112. |

[12] | Delgado, R. ((1989) ). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Michigan Law Review, 87: (8), 2411-2441. |

[13] | Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. ((2017) ). Critical race theory. In Critical Race Theory (Third Edition). New York University Press. |

[14] | Dow, M.J. ((2008) ). Implications of social presence for online learning: A case study of MLS students. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 231-24. |

[15] | Dunbar, A.W. ((2008) ). Critical race information theory: Applying a Critical race lens to Information Studies. University of California, Los Angeles. |

[16] | Evans, R. ((2022) ). In Burns-Simpson, S., Hayes, N.M., Walker, S., & Ndumu, A. Black librarians in America: Reflections, resistance, reawakening. Rowman & Littlefield, 2022. |

[17] | Gibson, A., Hughes-Hassell, S., & Threats, M. ((2018) ). Critical race theory in the LIS curriculum. In Re-envisioning the MLS: Perspectives on the Future of Library and Information Science Education, pp. 49-70. Emerald Publishing Limited. |

[18] | Givens, J.R. ((2021) ). Fugitive pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the art of Black teaching. Harvard University Press. |

[19] | Gray, L. ((2020) ). Empowered collective: Formulating a black feminist information community model through archival analysis. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 57: (1), e425. |

[20] | Hall, T.D. ((2012) ). The black body at the reference desk: Critical race theory and black librarianship, pp. 197-202. In Jackson, A.P, Jefferson, J., & Nosakhere, A. (2012). The 21st-century Black Librarian in America: Issues and Challenges, Rowman & Littlefield. |

[21] | Hathcock, A. ((2015) ). White librarianship in blackface: Diversity initiatives in LIS. In the Library with the Lead Pipe, 7: . |

[22] | Hartel, J. ((2014) ). An arts-informed study of information using the draw-and-write technique. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65: (7), 1349-1367. |

[23] | Honma, T. ((2005) ). Trippin’over the color line: The invisibility of race in library and information studies. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, 1: (2). https://escholarship.org/content/qt4nj0w1mp/qt4nj0w1mp.pdf. |

[24] | Honma, T. ((2021) ). Introduction to Part 1. In Leung, S.Y. & López-McKnight, J.R. (Eds.) Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies through Critical Race Theory, pp. 45-48. The MIT Press. |

[25] | Hudson, D.J. ((2017) ). On “diversity” as anti-racism in library and information studies: A critique. Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1: (1). http://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/6. |

[26] | Jardine, F.M., & Zerhusen, E.K. ((2015) ). Charting the Course of Equity and Inclusion in LIS through iDiversity. The Library Quarterly, 85: (2), 185-192. |

[27] | Jaeger, P.T., & Burnett, G. ((2010) ). Information worlds: Behavior, technology, and social context in the age of the Internet. Routledge. |

[28] | Kendrick, K.D., & Damasco, I.T. ((2019) ). Low morale in ethnic and racial minority academic librarians: An experiential study. Library Trends, 68: (2), 174-212. |

[29] | Kumasi, K.D. ((2012) ). Roses in the concrete: A critical race perspective on urban youth and school libraries. Knowledge Quest, 40: (5), 32-37. |

[30] | Leckie, G.J., Given, L.M., & Buschman, J. ((2010) ). Critical theory for library and information science: Exploring the social from across the disciplines. ABC-CLIO. |

[31] | Leung, S.Y., & López-McKnight, J.R. (Eds.) ((2021) ). Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies through Critical Race Theory. MIT Press. |

[32] | Ndumu, A., & Chancellor, R. ((2021) ). DuMont, 35 Years Later: HBCUs, LIS education, and institutional discrimination. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 62: (2), 162-181. |

[33] | Ndumu, A., & Walker, S. ((2021) ). Adapting an HBCU-inspired framework for Black student success in US LIS education. Education for Information, (Preprint), 1-11. |

[34] | Robinson, C.C., & Hullinger, H. ((2008) ). New benchmarks in higher education: Student engagement in online learning. Journal of Education for Business, 84: (2), 101-109. |

[35] | Stauffer, S.M. ((2020) ). Educating for whiteness: Applying critical race theory’s revisionist history in library and information science research: A methodology paper. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 61: (4), 452-462. |

[36] | Sweeney, M.E., & Cooke, N.A. ((2018) ). You’re so sensitive! How LIS professionals define and discuss microaggressions online. The Library Quarterly, 88: (4), 375-390. |

[37] | Walker, S. ((2015) ). Critical race theory and the recruitment, retention and promotion of a librarian of color: A counterstory. In Hankins, R. & Juarez, M., (Eds.) Where Are All the Librarians of Color?: The Experiences of People of Color in Academia, pp. 135-160. Library Juice Press. |

[38] | Walker, S.P. ((2017) ). “A revisionist history of Andrew Carnegie’s library grants to Black colleges.” In Schlesselman-Tarango, G., Ed. Topographies of Whiteness: Mapping Whiteness in Library and Information Science. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press. |

[39] | Walker, S. ((2021) ). Ann Allen Shockley: an activist-librarian for Black special collections. In Leung, S.Y. & López-McKnight, J.R. (Eds.) Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies through Critical Race Theory, pp. 159-175. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. |