Characterization of the Contribution of Genetic Background and Gender to Disease Progression in the SOD1 G93A Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

Background: The SOD1 G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the most frequently used model to examine ALS pathophysiology. There is a lack of homogeneity in usage of the SOD1 G93A mouse, including differences in genetic background and gender, which could confound the field’s results.

Objective: In an analysis of 97 studies, we characterized the ALS progression for the high transgene copy control SOD1 G93A mouse on the basis of disease onset, overall lifespan, and disease duration for male and female mice on the B6SJL and C57BL/6J genetic backgrounds and quantified magnitudes of differences between groups.

Methods: Mean age at onset, onset assessment measure, disease duration, and overall lifespan data from each study were extracted and statistically modeled as the response of linear regression with the sex and genetic background factored as predictors. Additional examination was performed on differing experimental onset and endpoint assessment measures.

Results: C57BL/6 background mice show delayed onset of symptoms, increased lifespan, and an extended disease duration compared to their sex-matched B6SJL counterparts. Female B6SJL generally experience extended lifespan and delayed onset compared to their male counterparts, while female mice on the C57BL/6 background show delayed onset but no difference in survival compared to their male counterparts. Finally, different experimental protocols (tremor, rotarod, etc.) for onset determination result in notably different onset means.

Conclusions: Overall, the observed effect of sex on disease endpoints was smaller than that which can be attributed to the genetic background. The often-reported increase in lifespan for female mice was observed only for mice on the B6SJL background, implicating a strain-dependent effect of sex on disease progression that manifests despite identical mutant SOD1 expression.

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons, muscular atrophy, functional deficits, paralysis, and death. ALS is frequently studied with the aid of animal models. In particular, the superoxide dismustase-1 glycine 93 to alanine mutation (SOD1 G93A) transgenic mouse model is widely utilized [36, 37] as it emulates the associated SOD1 mutations in human familial ALS [38] and exhibits pathological progression similar to that which is seen in human forms of the disease [39]. In fact, a PubMed search returns at the end of the 2014-year over 1,200 different articles containing “G93A” and “ALS”. Despite all of the numerous publications in this popular ALS mouse model, there remains controversy as to how genetic background, sex, and different experimental measures of disease onset and end point may or may not affect the outcomes of studies examining the SOD1 G93A pathophysiology or potential ALS treatments within this model.

Experimentally, the efficacy of a potential therapeutic treatment for ALS is evaluated on the basis of its effect on the parameters governing disease progression in the SOD1 G93A transgenic mouse, including age at onset, lifespan, disease duration, and motor performance. However, these parameters have been found to differ on the basis of transgenic copy number [40–42], genetic background [26–28], and sex [25, 43, 44] of the mice, all of which tend to vary in usage between studies. Additionally, the disease onset may be qualified through a variety of measures including gait abnormalities [45], limb tremors [46], electromyography [47], body weight declines [48], or deficits in motor performance tests, such as the rotarod [49] or grip [50] tests, each of which may differ from the others due to some difference in sensitivity of the test or through a variation in the underlying physiological mechanism being measured.

Prior studies commonly report delayed onset and progression of disease in females in both human [51] and mouse [43, 44, 47] variants of ALS. However, there have been conflicting reports in the literature as to the effect of sex and genetic background on SOD1 G93A disease onset and lifespan. Some studies report that female mice experience longer lifespans [44] in addition to delayed onset, while other studies find no difference in disease endpoint [47]. Additionally, the magnitude of the female-associated neuroprotective effect may vary on the basis of genetic background. In particular, Mancuso et al. [26] observed the female-associated protective effect on lifespan in mice bred on the C57BL/6 background, but not in B6SJL mice, which conflicts with the results of Heiman-Patterson [27] that report a sex-related effect on lifespan for mice on the B6SJL mice but not for those on the C57BL/6 background. As there is an inconsistency in the results reported by individual studies, it is of interest to resolve the conflicting results so the SOD1 G93A mouse model is better understood and potential therapeutics may be better predicted.

The lack of homogeneity in methodology between studies complicates comparative analysis in the SOD1 G93A field’s wealth of published data. The precise effect of genetic background, sex, and experimental measures of progression (rotarod, tremor, etc.) must be characterized to better assess the true impact of underlying disease mechanisms and potential therapeutics in both previous and future SOD1 G93A experimental studies. In this meta-analysis utilizing data from 97 studies, we characterize the disease progression parameters of onset, survival, and disease duration for the SOD1 G93A mouse and determine the effect of sex and genetic background on those parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion criteria

Data recapture was completed per previously published methodology [1]. Briefly, PubMed and Medline were searched in March 2013 for inclusion of articles based on the appearance of a combination of the following terms in the article title or abstract: “G93A”, “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis”, “ALS”, and “transgenic mouse”. That set was constrained by searching for the appearance of one or more of the following terms in the title, abstract, or figure caption: “onset”, “survival”, “lifespan”, “rotarod”, “motor performance”. The viability of each potential study was then manually determined. Included studies were those containing unique experimental data and citing the use of the high copy SOD1 G93A mouse from Jackson Laboratories (note that the overwhelming majority of studies do not quantitatively cite the actual number of transgene copies but rather only qualitatively state transgene copy number as being either “high” or “low”). Additional reported information required for study inclusion consisted of: mean mouse age at disease onset, mean mouse age at death, defined measures for calculation of disease progression, and clearly defined sample size information.

Data organization

Within each study of interest, independent groups of mice were defined as groups of mice used experimentally that exhibited a unique set of the following parameters: number of mice in the group, sex of the mice, genetic background, mean age at onset, and mean age at death. For each independent group of SOD1 G93A mice used experimentally within a study, the mean age at disease onset and death were tabulated. The disease duration was taken as the within-group difference between the mean survival and the mean onset. Additionally, the particular indicator used in the study for determining the time of disease onset was recorded and categorized.

Definitions of terms and categories

All included data are for the high copy number SOD1 G93A mouse model of ALS in the absence of treatment effects. Mice were categorized based on their genetic background as either originating from the B6SJL-Tg (SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J or the B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J lines. For the ease of discussion, mice of B6SJL-Tg(SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J and B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J lines will be referred to as “B6SJL” and “C57BL/6”, respectively. A group of mice was considered to be either male or female if that qualification fit all mice in the group and was considered mixed otherwise.

A diverse set of onset determination methodologies were broadly grouped in to four categories. Studies that defined onset through any sort of deficit in the rotarod test were deemed “Rotarod Decline”. Any mention of using tremors in the hindlimb as an indicator was deemed “Hindlimb Tremor” and references to tremors in the forelimb or non-specific locations were grouped as “Non-Hindlimb Tremor”. Onsets qualified through declines in bodyweight, gait abnormalities, limb paralysis, deficits in grip strength, and were grouped with articles without a specific definition of onset in to a catch-all category called “General”, due to the low overall usage of each of those methods.

Analytical methods

The disease progression parameters of age at onset, survival, and disease duration for the SOD1 G93A mouse were analyzed independently as the response variables of multiple ordinary least squares regression models in Stata (StataCorp, LP) with the genetic background and sex of the mice included as categorical predictors with full interaction. Each observation used in the calculation corresponds to an independent group of mice as defined by a unique combination of grouping factors and disease progression parameters with values for the disease progression parameters equal to the mean value of the parameter reported by the particular study. Observations were weighted in Stata on the basis of the group sample size and were factored as analytic weights [52], which are proportional to the inverse of the variance of the measure and normalized to the total number of points, giving results comparable to models weighted with the inverse variance directly [53]. Additional regression models were generated with the age at onset or survival included as an interacting continuous predictor when the response variable was survival or disease duration, as appropriate. The model with the largest R2 value was used for analysis. Post-estimation for the predicted mean value for specific combinations of covariates was computed with the “margins” command in Stata. The computed means are taken as the estimation on the interaction terms for the included groups and the results are plotted as categorical bar charts with significance between categories of mice determined through multiple comparisons, with the Bonferroni correction, on the margins output. In cases where continuous covariates were included as an interaction term, the estimation uses the integrated mean value for that particular categorization.

Analogous Cox proportional hazard regression models [54] were generated for each of onset, survival, and disease duration with the mean value from the study entering the model as count-time data with a frequency corresponding to the mice used in that study. Like the linear regression models, the regression was performed with full interaction of the categorical predictors. Predicted hazard ratios were obtained from the model and groups compared through multiple comparisons on the hazard ratios.

All statistical tests and models were computed in Stata (StataCorp LP). Graphics and tables were created in IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics). The significance level was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Data overview

The literature search returned 97 articles (Table 1) and 150 independent groups of mice with sufficient detail to fully characterize the data. The data is fully characterized if the article reports the mean onset, mean time of death, and sample size for each independent group and there must be enough information in the paper to categorize the groups in terms of genetic background, sex, and onset determination criteria. Of the articles surveyed, 85 groups of mice were classified as mixed sex, 37 groups were comprised solely of male mice, and 28 groups had only female mice. 91 groups were bred on the B6SJL background and 59 on the C57BL/6 (Table 1). Among mixed sex B6SJL articles, 12 report even distributions of males and females [2–13], 3 report uneven distributions without an overall bias [14–16], and the remainder report nothingconcerning sex distribution. Of the mixed sex C57BL/6 articles, 5 report balanced sex distributions [17–21], 4 have unbalanced groups with a slight overall bias towards male mice among the studies [22–25], while the remainder of the articles report nothing concerning the number of males and females. To determine onset of the disease, 34 articles used deficits in the rotarod test, 8 articles used the onset of hindlimb tremors, 9 articles looked at forelimb or non-specific tremors, and 46 articles fell into the miscellaneous “General”category.

Onset

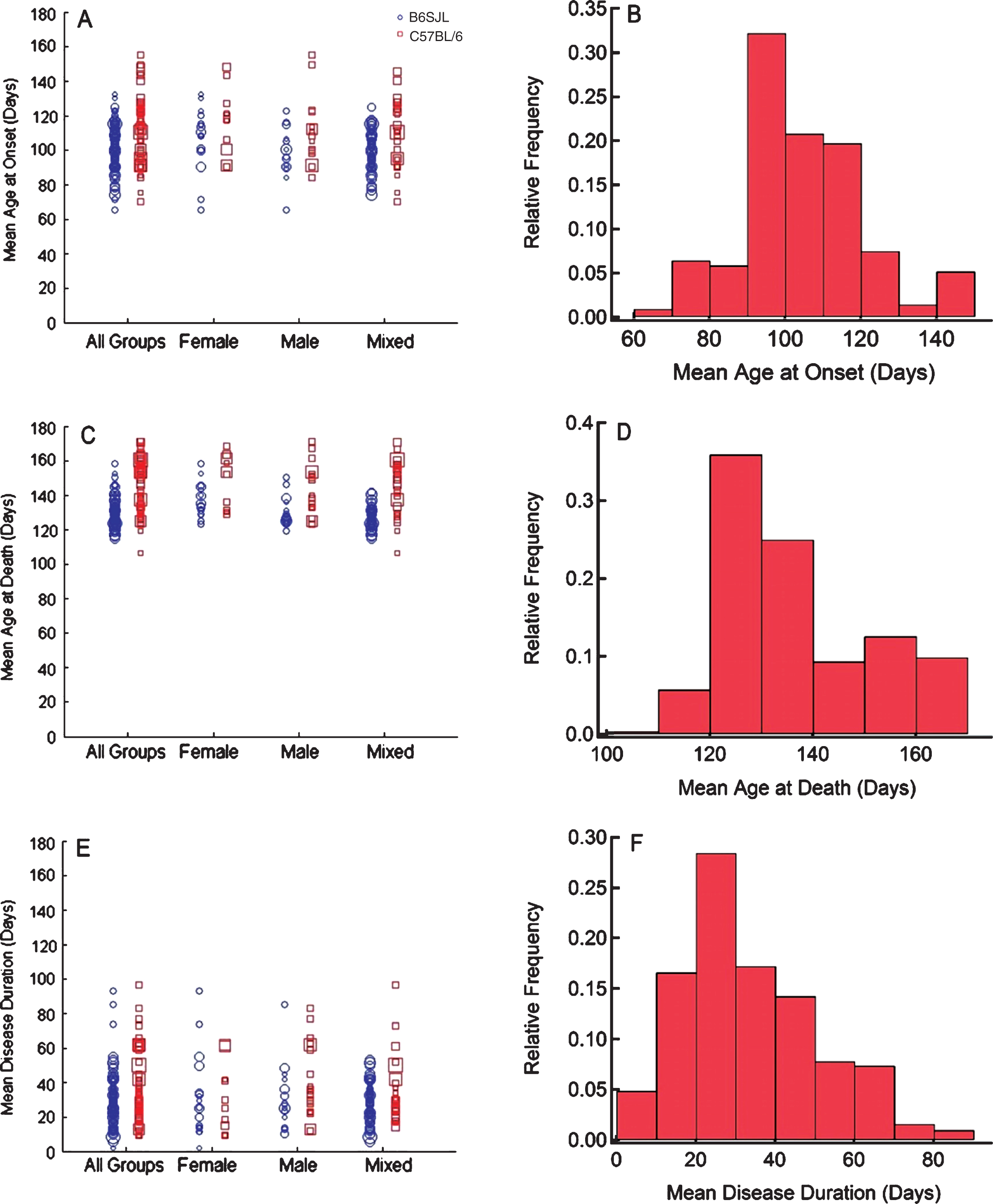

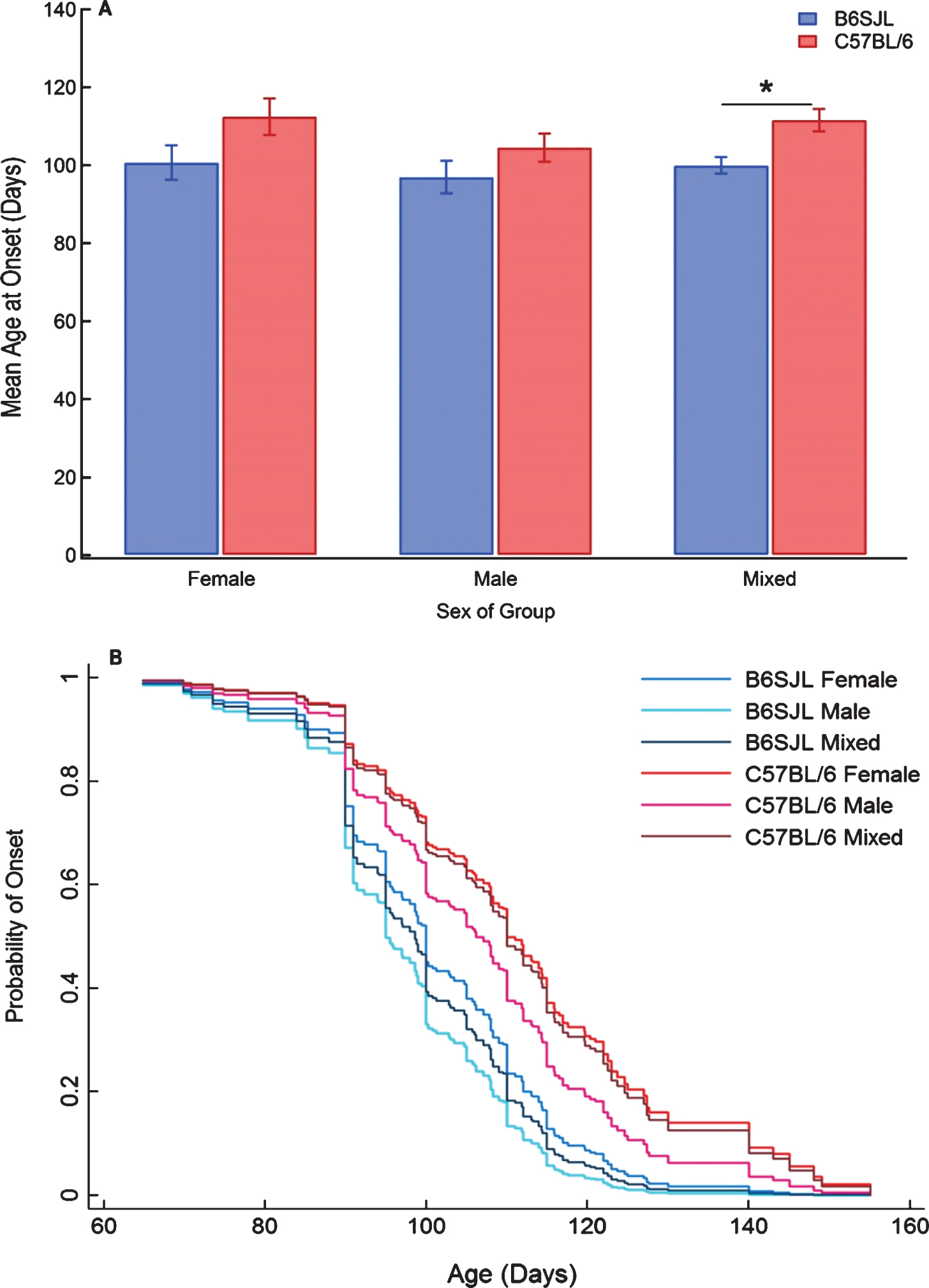

The raw data distributions show that the mean age at onset reported by the articles is most frequently in the range of 90 to 100 days (Fig. 1B) and the raw data plot qualitatively suggests that mice on the C57BL/6 background have later onsets than their B6SJL counterparts (Fig. 1A). When linear regression is run with onset as the response, genetic background strain is found to significantly impact the regression output (p = 0.002) and the effect of sex is found to be insignificant as a regression term and in subsequent multiple comparisons. The mixed sex mice were the only sex category to significantly differ on the basis of the genetic background (p = 0.002). The predicted mean onset was 99.86 ± 2.161 days for mixed sex B6SJL groups and 111.4 ± 2.857 days for the mixed C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2A). If strain is taken as the independent covariate, the main effect estimates onset as 99.27 ± 1.79 days for the B6SJL mice and 109.9 ± 2.063 days for the C57BL/6. It should be stated that although the mean onset is found to differ by the genetic background it is overall a poor sole predictor of onset as the adjusted R2 for this regression fit is low at 0.0776.

When the onset data are modeled as a Cox-proportional hazards, the predicted survival curve for disease onset shows a difference (p < 0.001) between the mice on the B6SJL and C57BL/6 genetic backgrounds (Fig. 2B). In contrast to the linear regression, this model predicts some difference in onset due to sex. Within the B6SJL group, female mice showed later onsets than male mice (p = 0.001) and the male C57BL/6 mice showed onsets earlier than both the mixed and female C57BL/6 mice (p < 0.001). No other comparisons were statistically significant.

Onset category

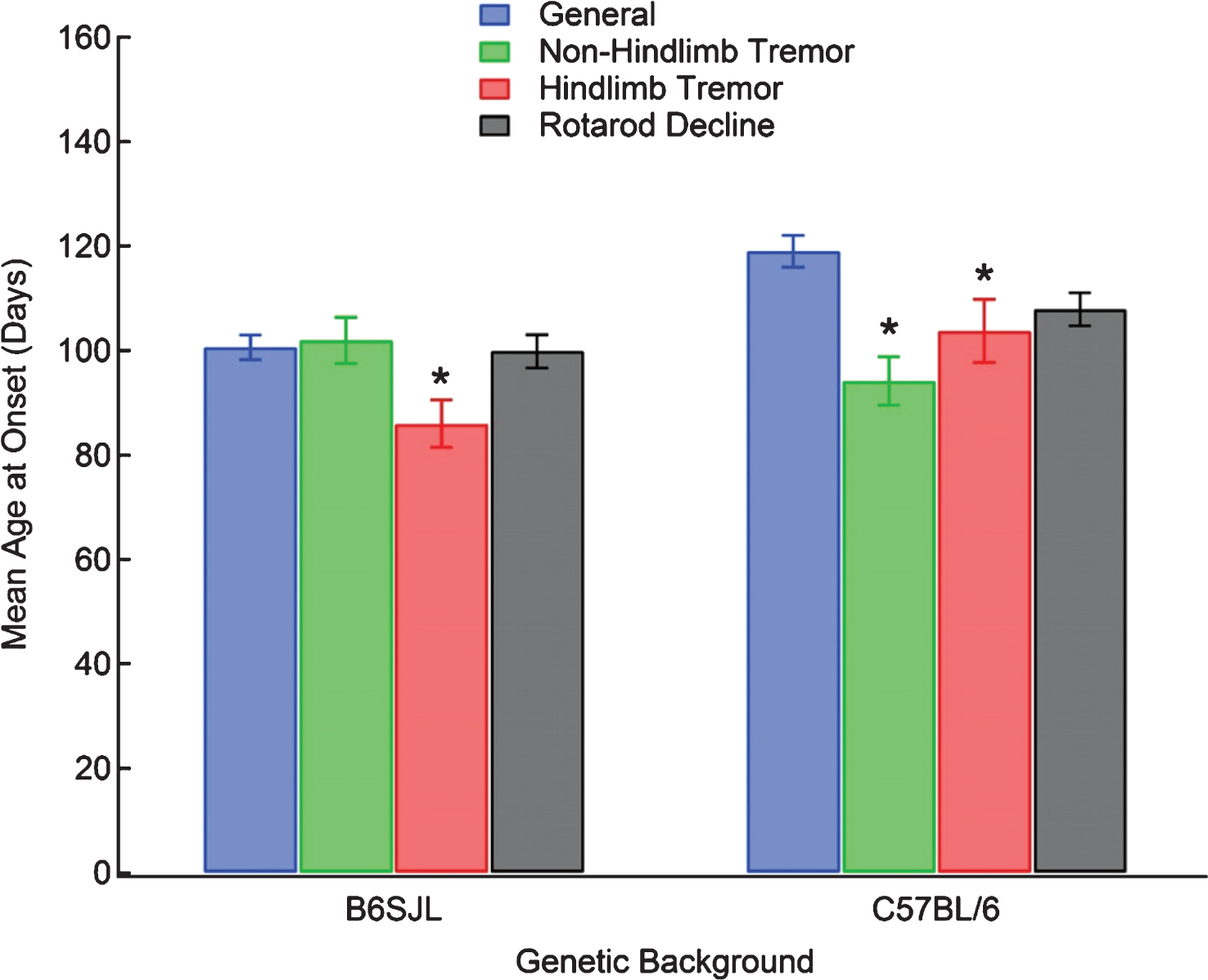

Differences in reported mean onsets between articles that defined their onset determination criteria were evaluated through regression with genetic background strain and the onset category included as categorical predictors (Fig. 3). The adjusted R2 for the model was 0.23. Within the B6SJL background, only hindlimb tremor with a mean onset of 85.93 ± 4.527 days was significantly different from the General category with a mean onset of 100.6 ± 2.330 days (p = 0.005). Within C57BL/6, the onsets determined by both hindlimb tremors and non-hindlimb tremors, with mean onsets of 103.7 ± 5.994 days and 94.06 ± 4.657 days, were found be significantly earlier than those of the General category with a mean onset of 118.9 ± 3.055 days (p = 0.025 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Survival

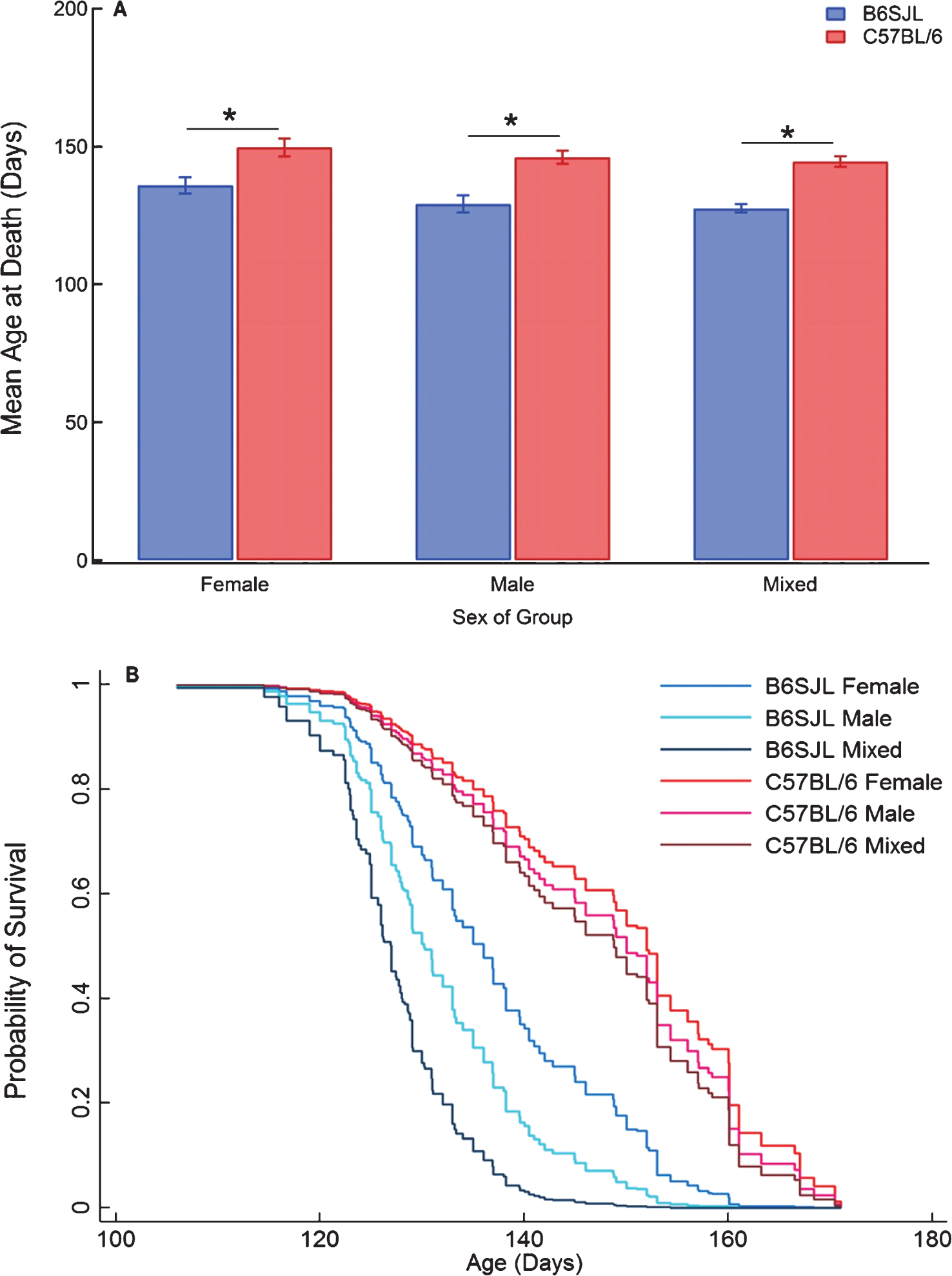

The histogram for the mean survival appears somewhat bimodal with one peak in the range of 120 to 130 days and another between 150 and 160 days (Fig. 1D). It follows from the raw data plot (Fig. 1C) that the first peak likely corresponds to the mean survival distribution for the B6SJL samples while the second peak fits more closely to the distribution of survival times for the C57BL/6, and the difference in magnitude is, in part, a product of the lower prevalence of C57BL/6 samples in the dataset. The regression output with survival as a response finds a significant difference between the two genetic background strains within each sex group (p < 0.05) with an adjusted R2 of 0.4867 when onset is included as a predictor (Fig. 4A). The predicted mean lifespans for each category with a representative onset were as follows: female B6SJL 135.77 ± 2.93 days, female C57BL/6 149.53 ± 3.30 days, male B6SJL 129.01 ± 3.1 days, male C57BL/6 145.95 ± 2.33 days, mixed sex B6SJL 127.39 ± 1.46 days, and mixed sex C57BL/6 144.4 ± 1.97 days. As in the case of linear model for onset, there were no within-strain differences due to sex after Bonferroni correction for this model. However, the survival curves generated from the analogous Cox model show a sex difference within the B6SJL background with the females surviving longer than the males or mixed groups (p < 0.001), with no sex differences found within C57BL/6 background mice (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the survival curves clearly show prolonged lifespan for the C57BL/6 background mice compared to their B6SJL counterparts (p < 0.001).

The result that the B6SJL mixed group survival is lower than both the male-only and female-only group is peculiar, as the onset results for the same data show what one would expect with respect to mixed mice (Fig. 2). To investigate this result, we iterated the model with subsets of the original data and with altered weights and found the separation of the mixed sex survival curve from the male and female curves to be a robust result. Given that greater than two-thirds of the mixed sex studies do not comment regarding gender bias or distribution (see Data Overview and Table 1), we cannot rule out unintended gender bias, which combined with statistical variation, could possibly account for the unexplained lower survival curve of the mixed sex groups, especially in B6SJL.

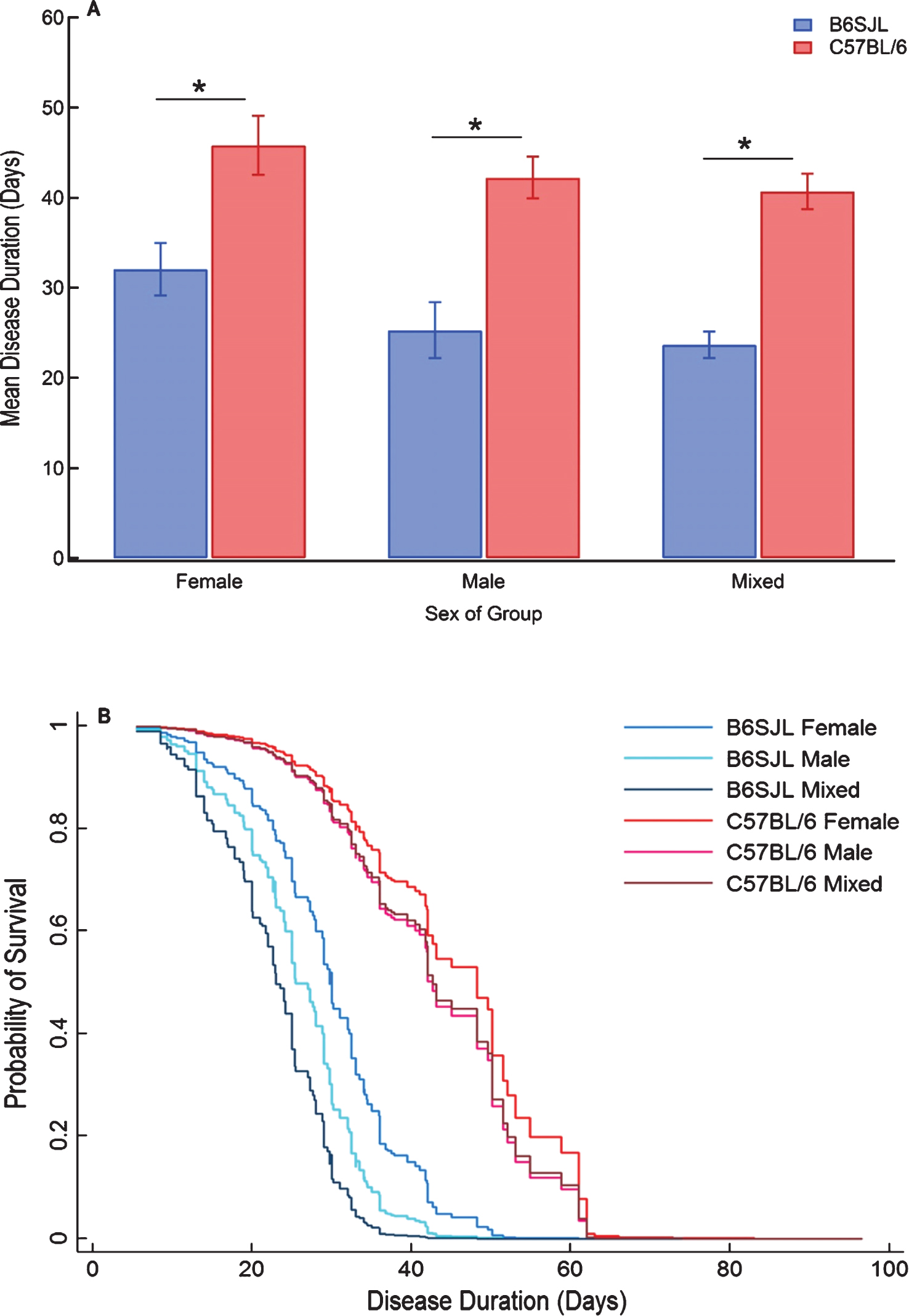

Disease duration

The disease duration data are distributed roughly normally with the majority of the data falling between 10 and 40 days (Fig. 1E). Three options for linear regression are available when duration is the response: onset or survival can be included as continuous interacting covariates or duration can be treated solely as a function of the categorical predictors. In the case of only categorical predictors, the adjusted R2 for the model is extremely low at 0.056. The addition of onset as a predictor in that model returns an adjusted R2 of 0.642 and the replacement of the onset term with survival gives an R2 of 0.225. The predicted mean outputs for the high fit model that includes onset as a predictor are shown in Fig. 5A. Within each sex group, the mice on a C57BL/6 background showed lengthened disease duration. There were no significantdifferences in disease duration due to sex within genetic background groups after Bonferroni correction. The predicted mean disease durations for the B6SJL and C57BL/6 mice were 25.49 ± 1.22 days and 41.95 ± 1.40 days, respectively. The Cox proportional hazards model with the probability of survival factored as the response at a particular day post-onset (Fig. 5B) shows a similar pattern to that which is seen when the age is used as the time point (Fig. 4B). Comparisons on the output imply that female mice in the B6SJL category exhibit longer disease duration than mixed mice (p = 0.009) and male groups (p = 0.054, Bonferroni corrected). Analogous to the survival model, this sex difference is not apparent within the C57BL/6 background groups, with no statistically significant differences between any of the C57BL/6 sex groups (p > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected) while overall the C57BL/6 mice show extended disease duration compared to the B6SJL mice (p = 0.001).

DISCUSSION

As the SOD1 G93A mouse is the primary animal model for ALS research, it is important that the diseaseprogression characteristics of commonly used variants of the model are known so that researchers may be better equipped to interpret their results. The results of this analysis confirm the existence of sex and genetic background related effects on disease endpoints. We find that the mice bred on the C57BL/6 background mice show delayed onset of disease, extended lifespan, and extended disease duration compared to their B6SJL counterparts. The often reported female-related neuroprotective protective effect on lifespan was only observed for B6SJL mice and not for those on C57BL/6 background, in corroboration with the results of Heiman-Patterson [27, 28] who reports a similar background-dependent effect of sex on disease, but these results conflict with the results of Mancuso [26]. However, the noted difference in result is not troubling, as the Heiman-Patterson study reports a larger colony size than Mancuso study. Overall, genetic background and sex had a smaller effect on measures of disease onset than they did on the lifespan or disease duration. This warrants further investigation, as our preliminary analysis into onset qualification methodology (Fig. 3) indicates that the variation in methodology used to determine onset is a large contributor to numerical variation in disease onset. As the experimental record expands in size, future comprehensive aggregate analysis that integrates quantitative measures of body weight, gait, motor performance tests, muscular size, EMG, and neuron counts in conjunction with genetic background and sex information has the potential to give insight into the mechanisms through which genetics affect the various systems associated with disease progression.

Sex

Overall, the expected difference in sex groups was not observed to a large degree when the mean predicted values in onset, lifespan, and disease duration are compared for the various linear models in that the difference is not statistically significant (p > 0.05 after Bonferroni correction). However, the subsequent survival analysis with Cox proportional hazards regression reveals the linear modeling technique to be conservative, as the minute qualitative difference observed between sex groups (Figs. 2A, 4A, 5A) becomes statistically significant when the hazard functions are compared (Figs. 2B, 4B, 5B), suggesting that the sex difference does exist, but is overshadowed by the larger effect due to genetic background when the data are modeled linearly. That comparison of hazard ratios suggests a small but significant effect of the female sex compared to males in terms of the onset for mice in both groups (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the magnitude of the sex difference is larger for the survival data (Fig. 4B), but only within the B6SJL group. Additionally, there are no differences in lifespan due to sex within the C57BL/6 group. Female mice in the B6SJL category showed longer disease duration than their mixed (p = 0.009) and male (p = 0.054 after Bonferroni correction) counterparts, but the effect was smaller than when the overall lifespan was compared. The existence of a strain-dependent effect of sex on the progression of disease implies that the inherent genetic differences observed between backgrounds have some interactive effect on the manifestation of the female hormone-related protective effect [43] and further investigation of this relationship may provide insight into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of ALS. For example, given that ALS is considered a multi-factorial disease, sex-dependent differences in disease progression and overall duration may only be present with certain types of underlying ALS etiologies rather than homogenously across all ALS phenotypes.

Genetic background

The results of this analysis imply that mice bred on the C57BL/6 genetic background experience disease onset and death at a later age than B6SJL mice and that the duration of disease in C57BL/6 mice is significantly extended. Survival and disease duration varied on the basis of genetic background within each sex group independently, but onset varied on the basis of genetic background only within the mixed sex group and when the results were aggregated. Without regards to sex, the mean onset and lifespan was found to be 99.27 ± 1.79 days and 130.23 ± 1.22 days for B6SJL background mice and 109.9 ± 2.06 days and 146.67 ± 1.42 days for C57BL/6 mice. The estimate for the B6SJL survival corresponds fairly well to the 128.9 ± 9.1 days [30] reported by Jackson Laboratories; however, the estimate for C57BL/6 survival poorly aligns with the 157.1 ± 9.3 days reported by Jackson Laboratories [30]. Previously, it has been shown that C57BL/6 background mice show deficits in motor neuron counts, compound muscle action potentials, and motor potentials two to four weeks earlier than their B6SJL counterparts [26] without a difference in onset measured by rotarod performance. As our results show a later onset and longer lifespan for the C57BL/6 mice, this implies that those mice experience milder symptoms despite a potentially more severe underlying pathology.

The mechanism through which the genetic background affects disease progression is unclear, but previous studies have shown that various mouse models exhibit phenotype variation that may affect ALS progression. These differences may manifest as variation in microglia-mediated neuro-inflammation [28, 29] and/or the progression or affect of hyperactivity of metabolic processes [30] inherent in ALS progression [31]. In particular, Jackson Laboratories reports hyperactivity of metabolism in terms of increased oxygen consumption, decreased circulating insulin levels, abnormal energy expenditures, etc. in the B6SJL mice but not for C57BL/6 mice [30], potentially explaining the more rapid progression of disease in the B6SJL mice.

On a similar note, a recent study of non-familial clinical ALS patients showed that antecedent disease is substantially less prevalent among ALS patients, including metabolic disturbances like diabetes, obesity and thyroid disease, which suggests the possibility of neuroprotection— either “other disease is protective of ALS” or “ALS is protective of other disease” [32]. In fact, the pathophysiological process oscillations seen in models examining the SOD1 G93A underlying pathophysiology, suggest the possibility of “hypervigilant regulation” (in control theory a too-high feedback gain). Regulatory delays combined with the too-high feedback gain(s) of hypervigilant regulation, could ultimately result in system instabilities identified in the SOD1 G93A model that dramatically impact the onset and progression of ALS [32–34]. In short, genetic differences underlying cellular and systemic regulation could result in different ALS phenotypes, both in transgenic mouse models and in humans. Further assessment of pathology dynamics will help to distinguish phenotypic characteristics [32, 33, 35].

Onset category

It is of interest to the field to characterize the time course of the onset of various symptoms for each mouse variant so that individual results can be better understood and gauged in the context of other studies. There are differences in the sensitivities of various measures of onset to detect specific aspects of the underlying pathophysiology [25, 55]. Some researchers utilize a graded motor score that accounts for visualized gait impairments, limb tremors, and motor deficits [56, 57], but those systems are not standardized between studies. The linear modeling method used to investigate sex and genetic background is easily extended to allow for onset characterization to be analyzed as a categorical covariate. Within both the B6SJL and C57BL/6 background groups, onsets due to tremors were developed at an earlier age than the control grouping, which is consistent with reports that tremors develop prior to outright motor deficits [58]. Bodyweight declines are often cited as developing prior to or in sync with the development of tremors [59], but we were unable to test this directly due to the low prevalence of bodyweight onsets in the dataset.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the analysis of data from 97 articles confirmed that the SOD1 G93A mouse lifespan, disease duration, and onset vary largely between the two most widely used genetic backgrounds, with those bred on the C57BL/6 background showing a milder delayed onset of disease with increased lifespans and longer disease duration when compared to the B6SJL mouse. The expected delayed onset and extended lifespan typically reported in female mice was observed only in SOD1 G93A mice on the B6SJL background, and the effect was altogether small compared to the strain difference. The existence of a strain-dependent effect of sex on the progression of disease demonstrates the importance of the proper identification of group-specific characteristics and their potential relationships to the underlying pathophysiology. Finally, different onset determination protocols (general, rotarod, tremor, etc.) can result in notably different mean onsets. Based on the initial analysis of this study, it appears that tremors or grasping protocols are more sensitive for onset determination whereas motor function protocols like rotarod are better for determining motor deficit progression and endpoint; however, further analysis is needed to confirm this finding. Like all fields, the SOD1 G93A transgenic mouse field would benefit from greater consistency and documentation in experimental methodology to assist in consolidating conflicting pathophysiology assessment and/or treatments and lessen the impact of confounding variables [33, 60].

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding provided by National Institute of Health grants NS081426 and NS069616 to CSM.

REFERENCES

1 | Mitchell CS, Halicek M, Kim R, Tilva K, Lee RH(2013) in Society for NeuroscienceSan Diego, CA |

2 | Turner BJ, Lopes EC, Cheema SS(2003) The serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan delays neuromuscular disease in murine familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisAmyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord4: 171176 |

3 | Wu AS, Kiaei M, Aguirre N, Crow JP, Calingasan NY, Browne SE, Beal MF(2003) Iron porphyrin treatment extends survival in a transgenic animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurochem85: 142150 |

4 | Fischer LR, Culver DG, Tennant P, Davis AA, Wang M, Castellano-Sanchez A, Khan J, Polak MA, Glass JD(2004) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: Evidence in mice and manExp Neurol185: 232240 |

5 | Kaspar BK, Frost LM, Christian L, Umapathi P, Gage FH(2005) Synergy of insulin-like growth factor-1 and exercise in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisAnn Neurol57: 649655 |

6 | Petri S, Kiaei M, Damiano M, Hiller A, Wille E, Manfredi G, Calingasan NY, Szeto HH, Beal MF(2006) Cell-permeable peptide antioxidants as a novel therapeutic approach in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurochem98: 11411148 |

7 | Solomon JN, Lewis CA, Ajami B, Corbel SY, Rossi FM, Krieger C(2006) Origin and distribution of bone marrow-derived cells in the central nervous system in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisGlia53: 744753 |

8 | Towne C, Raoul C, Schneider BL, Aebischer P(2008) Systemic AAV6 delivery mediating RNA interference against SOD Neuromuscular transduction does not alter disease progression in fALS miceMol Ther16: 10181025 |

9 | Neymotin A, Petri S, Calingasan NY, Wille E, Schafer P, Stewart C, Hensley K, Beal MF, Kiaei M(2009) Lenalidomide (Revlimid) administration at symptom onset is neuroprotective in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisExp Neurol220: 191197 |

10 | Sekiya M, Ichiyanagi T, Ikeshiro Y, Yokozawa T(2009) The Chinese prescription Wen-Pi-Tang extract delays disease onset in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model mice while attenuating the activation of glial cells in the spinal cordBiol Pharm Bull32: 382388 |

11 | Knippenberg S, Thau N, Dengler R, Petri S(2010) Significance of behavioural tests in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)Behav Brain Res213: 8287 |

12 | Calvo AC, Moreno-Igoa M, Mancuso R, Manzano R, Olivan S, Munoz MJ, Penas C, Zaragoza P, Navarro X, Osta R(2011) Lack of a synergistic effect of a non-viral ALS gene therapy based on BDNF and a TTC fusion moleculeOrphanet J Rare Dis6: 10 |

13 | Genestine M, Caricati E, Fico A, Richelme S, Hassani H, Sunyach C, Lamballe F, Panzica GC, Pettmann B, Helmbacher F, Raoul C, Maina F, Dono R(2011) Enhanced neuronal Met signalling levels in ALS mice delay disease onsetCell Death Dis2: e130 |

14 | Liebetanz D, Hagemann K, von Lewinski F, Kahler E, Paulus W(2004) Extensive exercise is not harmful in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisEur J Neurosci20: 31153120 |

15 | West M, Mhatre M, Ceballos A, Floyd RA, Grammas P, Gabbita SP, Hamdheydari L, Mai T, Mou S, Pye QN, Stewart C, West S, Williamson KS, Zemlan F, Hensley K(2004) The arachidonic acid 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor nordihydroguaiaretic acid inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha activation of microglia and extends survival of G93A-SOD1 transgenic miceJ Neurochem91: 133143 |

16 | Hamadeh MJ, Rodriguez MC, Kaczor JJ, Tarnopolsky MA(2005) Caloric restriction transiently improves motor performance but hastens clinical onset of disease in the Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant G93A mouseMuscle Nerve31: 214220 |

17 | Corti S, Locatelli F, Donadoni C, Guglieri M, Papadimitriou D, Strazzer S, Del Bo R, Comi GP(2004) Wild-type bone marrow cells ameliorate the phenotype of SOD1-G93A ALS mice and contribute to CNS heart and skeletal muscle tissuesBrain127: 25182532 |

18 | Corti S, Locatelli F, Papadimitriou D, Del Bo R, Nizzardo M, Nardini M, Donadoni C, Salani S, Fortunato F, Strazzer S, Bresolin N, Comi GP(2007) Neural stem cells LewisX+ CXCR4+ modify disease progression in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis modelBrain130: 12891305 |

19 | Turner BJ, Ackerley S, Davies KE, Talbot K(2010) Dismutase-competent SOD1 mutant accumulation in myelinating Schwann cells is not detrimental to normal or transgenic ALS model miceHum Mol Genet19: 815824 |

20 | Dibaj P, Zschuntzsch J, Steffens H, Scheffel J, Goricke B, Weishaupt JH, Le Meur K, Kirchhoff F, Hanisch UK, Schomburg ED, Neusch C(2012) Influence of methylene blue on microglia-induced inflammation and motor neuron degeneration in the SOD1(G93A) model for ALSPLoS One7: e43963 |

21 | Ringer C, Buning LS, Schafer MK, Eiden LE, Weihe E, Schutz B(2013) PACAP signaling exerts opposing effects on neuroprotection and neuroinflammation during disease progression in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurobiol Dis54: 3242 |

22 | Chiba T, Hashimoto Y, Tajima H, Yamada M, Kato R, Niikura T, Terashita K, Schulman H, Aiso S, Kita Y, Matsuoka M, Nishimoto I(2004) Neuroprotective effect of activity-dependent neurotrophic factor against toxicity from familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant SOD1 in vitro and in vivo J Neurosci Res78: 542552 |

23 | Chiba T, Yamada M, Sasabe J, Terashita K, Aiso S, Matsuoka M, Nishimoto I(2006) Colivelin prolongs survival of an ALS model mouseBiochem Biophys Res Commun343: 793798 |

24 | Crosio C, Casciati A, Iaccarino C, Rotilio G, Carri MT(2006) Bcl2a1 serves as a switch in death of motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisCell Death Differ13: 21502153 |

25 | Hayworth CR, Gonzalez-Lima F(2009) Pre-symptomatic detection of chronic motor deficits and genotype prediction in congenic B6.SOD1(G93A) ALS mouse modelNeuroscience164: 975985 |

26 | Mancuso R, Olivan S, Mancera P, Pasten-Zamorano A, Manzano R, Casas C, Osta R, Navarro X(2012) Effect of genetic background on onset and disease progression in the SOD1-G93A model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisAmyotroph Lateral Scler13: 302310 |

27 | Heiman-Patterson TD, Deitch JS, Blankenhorn EP, Erwin KL, Perreault MJ, Alexander BK, Byers N, Toman I, Alexander GM(2005) Background and gender effects on survival in the TgN(SOD1-G93A)1Gur mouse model of ALSJ Neurol Sci236: 17 |

28 | Heiman-Patterson TD, Sher RB, Blankenhorn EA, Alexander G, Deitch JS, Kunst CB, Maragakis N, Cox G(2011) Effect of genetic background on phenotype variability in transgenic mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A window of opportunity in the search for genetic modifiersAmyotroph Lateral Scler12: 7986 |

29 | Nikodemova M, Watters JJ(2011) Outbred ICR/CD1 mice display more severe neuroinflammation mediated by microglial TLR4/CD14 activation than inbred C57Bl/6 miceNeuroscience190: 6774 |

30 | Mouse Genome Database (MGD) at the Mouse Genome Informatics website, The Jackson Laboratory, http://www.informatics.jax.org, Accessed December 7 |

31 | Dupuis L, Pradat P-F, Ludolph AC, Loeffler J-P(2011) Energy metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The LancetNeurology10: 7582 |

32 | Mitchell CS, Hollinger SK, Goswami SD, Polak M, Lee RH, Glass JD(2015) Antecedent disease is less prevalent in Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisNeurodegener Dis14: (Accepted 11/11/ Issue not yet assigned) |

33 | Mitchell, C. S., Lee, R. H. In Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis InTech, 2012. http://www.intechopen.com/books/amyotrophic-lateral-sclerosis/dynamic-meta-analysis-as-a-therapeutic-prediction-tool-for-amyotrophic-lateral-sclerosis |

34 | Mitchell CS, Lee RH(2012) Cargo distributions differentiate pathological axonal transport impairmentsJ Theor Biol300: 277291 |

35 | Mitchell CS, Lee RH(2008) Pathology dynamics predict spinal cord injury therapeutic successJ Neurotrauma25: 14831497 |

36 | Gurney ME(1997) Transgenic animal models of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurol244: Suppl 2S15S20 |

37 | Gurney ME(1994) Transgenic-mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisN Engl J Med331: 17211722 |

38 | Siddique T, Deng HX(1996) Genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisHum Mol Genet5 Spec No: 14651470 |

39 | Synofzik M, Fernandez-Santiago R, Maetzler W, Schols L, Andersen PM(2010) The human G93A SOD1 phenotype closely resembles sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry81: 764767 |

40 | Acevedo-Arozena A, Kalmar B, Essa S, Ricketts T, Joyce P, Kent R, Rowe C, Parker A, Gray A, Hafezparast M, Thorpe JR, Greensmith L, Fisher EM(2011) A comprehensive assessment of the SOD1G93A low-copy transgenic mouse, which models human amyotrophic lateral sclerosisDis Model Mech4: 686700 |

41 | Ripps ME, Huntley GW, Hof PR, Morrison JH, Gordon JW(1995) Transgenic mice expressing an altered murine superoxide dismutase gene provide an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisProc Natl Acad Sci U S A92: 689693 |

42 | Wooley CM, Sher RB, Kale A, Frankel WN, Cox GA, Seburn KL(2005) Gait analysis detects early changes in transgenic SOD1(G93A) miceMuscle Nerve32: 4350 |

43 | Bame M, Pentiak PA, Needleman R, Brusilow WS(2012) Effect of sex on lifespan, disease progression, and the response to methionine sulfoximine in the SOD1 G93A mouse model for ALSGend Med9: 524535 |

44 | Choi CI, Lee YD, Gwag BJ, Cho SI, Kim SS, Suh-Kim H(2008) Effects of estrogen on lifespan and motor functions in female hSOD1 G93A transgenic miceJ Neurol Sci268: 4047 |

45 | Steinacker P, Hawlik A, Lehnert S, Jahn O, Meier S, Gorz E, Braunstein KE, Krzovska M, Schwalenstocker B, Jesse S, Propper C, Bockers T, Ludolph A, Otto M(2010) Neuroprotective function of cellular prion protein in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisAm J Pathol176: 14091420 |

46 | Li W, Brakefield D, Pan Y, Hunter D, Myckatyn TM, Parsadanian A(2007) Muscle-derived but not centrally derived transgene GDNF is neuroprotective in G93A-SOD1 mouse model of ALSExp Neurol203: 457471 |

47 | Miana-Mena FJ, Munoz MJ, Yague G, Mendez M, Moreno M, Ciriza J, Zaragoza P, Osta R(2005) Optimal methods to characterize the G93A mouse model of ALSAmyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord6: 5562 |

48 | Shimojo Y, Kosaka K, Noda Y, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T(2010) Effect of rosmarinic acid in motor dysfunction and life span in a mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurosci Res88: 896904 |

49 | Kiaei M, Kipiani K, Petri S, Chen J, Calingasan NY, Beal MF(2005) Celastrol blocks neuronal cell death and extends life in transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurodegener Dis2: 246254 |

50 | Schutz B, Reimann J, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Kappes-Horn K, Landreth GE, Schurmann B, Zimmer A, Heneka MT(2005) The oral antidiabetic pioglitazone protects from neurodegeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like symptoms in superoxide dismutase-G93A transgenic miceJ Neurosci25: 78057812 |

51 | McCombe PA, Henderson RD(2010) Effects of gender in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisGend Med7: 557570 |

52 | (2013) StataCorp LP, College Station, TX |

53 | Cruz-Sanchez FF, Moral A, Rossi ML, Quinto L, Castejon C, Tolosa E, de Belleroche J(1996) Synaptophysin in spinal anterior horn in aging and ALS: An immunohistological studyJ Neural Transm103: 13171329 |

54 | Cox D(1992) Regression Models and Life-Tables In Breakthroughs in StatisticsKotz S, Johnson NSpringerNew York527541 |

55 | Lepore AC, O’Donnell J, Kim AS, Williams T, Tuteja A, Rao MS, Kelley LL, Campanelli JT, Maragakis NJ(2011) Human glial-restricted progenitor transplantation into cervical spinal cord of the SOD1 mouse model of ALSPLoS One6: e25968 |

56 | Alves CJ, de Santana LP, dos Santos AJ, de Oliveira GP, Duobles T, Scorisa JM, Martins RS, Maximino JR, Chadi G(1394) Early motor and electrophysiological changes in transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and gender differences on clinical outcomeBrain Res90104 |

57 | Lerman BJ, Hoffman EP, Sutherland ML, Bouri K, Hsu DK, Liu FT, Rothstein JD, Knoblach SM(2012) Deletion of galectin-3 exacerbates microglial activation and accelerates disease progression and demise in a SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisBrain Behav2: 563575 |

58 | Kasai A, Kinjo T, Ishihara R, Sakai I, Ishimaru Y, Yoshioka Y, Yamamuro A, Ishige K, Ito Y, Maeda S(2011) Apelin deficiency accelerates the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisPLoS One6: e23968 |

59 | Matsumoto A, Okada Y, Nakamichi M, Nakamura M, Toyama Y, Sobue G, Nagai M, Aoki M, Itoyama Y, Okano H(2006) Disease progression of human SOD1 (G93A) transgenic ALS model ratsJournal Of Neuroscience Research83: 119133 |

60 | Foley AM, Ammar ZM, Lee RH, Mitchell CS(2015) Systematic review of the relationship between amyloid-beta levels and measures of transgenic mouse cognitive deficit in Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Alzheimers Dis44: 787795 |

61 | Ferrante RJ, Klein AM, Dedeoglu A, Beal MF(2001) Therapeutic efficacy of EGb761 (Gingko biloba extract) in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Mol Neurosci17: 8996 |

62 | Azari MF, Lopes EC, Stubna C, Turner BJ, Zang D, Nicola NA, Kurek JB, Cheema SS(2003) Behavioural and anatomical effects of systemically administered leukemia inhibitory factor in the SOD1(G93A G1H) mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisBrain Res982: 9297 |

63 | Pompl PN, Ho L, Bianchi M, McManus T, Qin W, Pasinetti GM(2003) A therapeutic role for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisFASEB J17: 725727 |

64 | Zheng C, Nennesmo I, Fadeel B, Henter JI(2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of ALSAnn Neurol56: 564567 |

65 | Schutz B(2005) Imbalanced excitatory to inhibitory synaptic input precedes motor neuron degeneration in an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurobiol Dis20: 131140 |

66 | Ito H, Wate R, Zhang J, Ohnishi S, Kaneko S, Ito H, Nakano S, Kusaka H(2008) Treatment with edaravone initiated at symptom onset, slows motor decline and decreases SOD1 deposition in ALS miceExp Neurol213: 448455 |

67 | Rohde G, Kermer P, Reed JC, Bahr M, Weishaupt JH(2008) Neuron-specific overexpression of the co-chaperone Bcl-2-associated athanogene-1 in superoxide dismutase 1(G93A)-transgenic miceNeuroscience157: 844849 |

68 | Smittkamp SE, Brown JW, Stanford JA(2008) Time-course and characterization of orolingual motor deficits in B6SJL-Tg(SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J miceNeuroscience151: 613621 |

69 | Stam NC, Nithianantharajah J, Howard ML, Atkin JD, Cheema SS, Hannan AJ(2008) Sex-specific behavioural effects of environmental enrichment in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisEur J Neurosci28: 717723 |

70 | Gianforcaro A, Hamadeh MJ(2012) Dietary vitamin D3 supplementation at 10x the adequate intake improves functional capacity in the G93A transgenic mouse model of ALS, a pilot studyCNS Neurosci Ther18: 547557 |

71 | Knippenberg S, Thau N, Schwabe K, Dengler R, Schambach A, Hass R, Petri S(2012) Intraspinal injection of human umbilical cord blood-derived cells is neuroprotective in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurodegener Dis9: 107120 |

72 | Gianforcaro A, Solomon JA, Hamadeh MJ(2013) Vitamin D(3) at 50x AI attenuates the decline in paw grip endurance, but not disease outcomes, in the G93A mouse model of ALS, and is toxic in femalesPLoS One8: e30243 |

73 | Chiu AY, Zhai P, Dal Canto MC, Peters TM, Kwon YW, Prattis SM, Gurney ME(1995) Age-dependent penetrance of disease in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisMol Cell Neurosci6: 349362 |

74 | Hamadeh MJ, Tarnopolsky MA(2006) Transient caloric restriction in early adulthood hastens disease endpoint in male, but not female, Cu/Zn-SOD mutant G93A miceMuscle Nerve34: 709719 |

75 | Ohta Y, Nagai M, Nagata T, Murakami T, Nagano I, Narai H, Kurata T, Shiote M, Shoji M, Abe K(2006) Intrathecal injection of epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2 promotes proliferation of neural precursor cells in the spinal cords of mice with mutant human SOD1 geneJ Neurosci Res84: 980992 |

76 | Marcuzzo S, Zucca I, Mastropietro A, de Rosbo NK, Cavalcante P, Tartari S, Bonanno S, Preite L, Mantegazza R, Bernasconi P(2011) Hind limb muscle atrophy precedes cerebral neuronal degeneration in G93A-SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A longitudinal MRI studyExp Neurol231: 3037 |

77 | Zhao Z, Lange DJ, Voustianiouk A, MacGrogan D, Ho L, Suh J, Humala N, Thiyagarajan M, Wang J, Pasinetti GM(2006) A ketogenic diet as a potential novel therapeutic intervention in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisBMC Neurosci7: 29 |

78 | Hottinger AF, Fine EG, Gurney ME, Zurn AD, Aebischer P(1997) The copper chelator d-penicillamine delays onset of disease and extends survival in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisEur J Neurosci9: 15481551 |

79 | Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, Klivenyi P, Beal MF, Bush AI(2000) N-acetyl-L-cysteine improves survival and preserves motor performance in an animal model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeuroreport11: 24912493 |

80 | Li M, Ona VO, Guegan C, Chen M, Jackson-Lewis V, Andrews LJ, Olszewski AJ, Stieg PE, Lee JP, Przedborski S, Friedlander RM(2000) Functional role of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in an ALS transgenic mouse modelScience288: 335339 |

81 | Acsadi G, Anguelov RA, Yang H, Toth G, Thomas R, Jani A, Wang Y, Ianakova E, Mohammad S, Lewis RA, Shy ME(2002) Increased survival and function of SOD1 mice after glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor gene therapyHum Gene Ther13: 10471059 |

82 | Drachman DB, Frank K, Dykes-Hoberg M, Teismann P, Almer G, Przedborski S, Rothstein JD(2002) Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition protects motor neurons and prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of ALSAnn Neurol52: 771778 |

83 | Wang LJ, Lu YY, Muramatsu S, Ikeguchi K, Fujimoto K, Okada T, Mizukami H, Matsushita T, Hanazono Y, Kume A, Nagatsu T, Ozawa K, Nakano I(2002) Neuroprotective effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor mediated by an adeno-associated virus vector in a transgenic animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurosci22: 69206928 |

84 | Guo H, Lai L, Butchbach ME, Stockinger MP, Shan X, Bishop GA, Lin CL(2003) Increased expression of the glial glutamate transporter EAAT2 modulates excitotoxicity and delays the onset but not the outcome of ALS in miceHum Mol Genet12: 25192532 |

85 | Turner BJ, Lopes EC, Cheema SS(2003) Neuromuscular accumulation of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 aggregates in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurosci Lett350: 132136 |

86 | Takahashi S, Kulkarni AB(2004) Mutant superoxide dismutase 1 causes motor neuron degeneration independent of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activation by p35 or p25J Neurochem88: 12951304 |

87 | Day WA, Koishi K, Nukuda H, McLennan IS(2005) Transforming growth factor-beta 2 causes an acute improvement in the motor performance of transgenic ALS miceNeurobiol Dis19: 323330 |

88 | Gilchrist CA, Gray DA, Stieber A, Gonatas NK, Kopito RR(2005) Effect of ubiquitin expression on neuropathogenesis in a mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeuropathol Appl Neurobiol31: 2033 |

89 | Kiaei M, Kipiani K, Chen J, Calingasan NY, Beal MF(2005) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist extends survival in transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisExp Neurol191: 331336 |

90 | Kiaei M, Petri S, Kipiani K, Gardian G, Choi DK, Chen J, Calingasan NY, Schafer P, Muller GW, Stewart C, Hensley K, Beal MF(2006) Thalidomide and lenalidomide extend survival in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurosci26: 24672473 |

91 | Koh SH, Lee SM, Kim HY, Lee KY, Lee YJ, Kim HT, Kim J, Kim MH, Hwang MS, Song C, Yang KW, Lee KW, Kim SH, Kim OH(2006) The effect of epigallocatechin gallate on suppressing disease progression of ALS model miceNeurosci Lett395: 103107 |

92 | Lorenzl S, Narr S, Angele B, Krell HW, Gregorio J, Kiaei M, Pfister HW, Beal MF(2006) The matrix metalloproteinases inhibitor Ro 28-[correction of Ro 26-] extends survival in transgenic ALS miceExp Neurol200: 166171 |

93 | Petri S, Kiaei M, Kipiani K, Chen J, Calingasan NY, Crow JP, Beal MF(2006) Additive neuroprotective effects of a histone deacetylase inhibitor and a catalytic antioxidant in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurobiol Dis22: 4049 |

94 | Weishaupt JH, Bartels C, Polking E, Dietrich J, Rohde G, Poeggeler B, Mertens N, Sperling S, Bohn M, Huther G, Schneider A, Bach A, Siren AL, Hardeland R, Bahr M, Nave KA, Ehrenreich H(2006) Reduced oxidative damage in ALS by high-dose enteral melatonin treatmentJ Pineal Res41: 313323 |

95 | Glas M, Popp B, Angele B, Koedel U, Chahli C, Schmalix WA, Anneser JM, Pfister HW, Lorenzl S(2007) A role for the urokinase-type plasminogen activator system in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisExp Neurol207: 350356 |

96 | Joo IS, Hwang DH, Seok JI, Shin SK, Kim SU(2007) Oral administration of memantine prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Clin Neurol3: 181186 |

97 | Wang H, Guan Y, Wang X, Smith K, Cormier K, Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Huo C, Ferrante RJ, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM(2007) Nortriptyline delays disease onset in models of chronic neurodegenerationEur J Neurosci26: 633641 |

98 | Garbuzova-Davis S, Sanberg CD, Kuzmin-Nichols N, Willing AE, Gemma C, Bickford PC, Miller C, Rossi R, Sanberg PR(2008) Human umbilical cord blood treatment in a mouse model of ALS: Optimization of cell dosePLoS One3: e2494 |

99 | Lev N, Ickowicz D, Barhum Y, Melamed E, Offen D(2009) DJ-1 changes in G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice: Implications for oxidative stress in ALSJ Mol Neurosci38: 94102 |

100 | Shimazawa M, Tanaka H, Ito Y, Morimoto N, Tsuruma K, Kadokura M, Tamura S, Inoue T, Yamada M, Takahashi H, Warita H, Aoki M, Hara H(2010) An inducer of VGF protects cells against ER stress-induced cell death and prolongs survival in the mutant SOD1 animal models of familial ALSPLoS One5: e15307 |

101 | Moreno-Igoa M, Calvo AC, Ciriza J, Munoz MJ, Zaragoza P, Osta R(2012) Non-viral gene delivery of the GDNF, either alone or fused to the C-fragment of tetanus toxin protein, prolongs survival in a mouse ALS modelRestor Neurol Neurosci30: 6980 |

102 | Zhou C, Zhang C, Zhao R, Chi S, Ge P, Zhang C(2013) Human marrow stromal cells reduce microglial activation to protect motor neurons in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neuroinflammation10: 52 |

103 | Van Den Bosch L, Tilkin P, Lemmens G, Robberecht W(2002) Minocycline delays disease onset and mortality in a transgenic model of ALSNeuroreport13: 10671070 |

104 | Pardo AC, Wong V, Benson LM, Dykes M, Tanaka K, Rothstein JD, Maragakis NJ(2006) Loss of the astrocyte glutamate transporter GLT1 modifies disease in SOD1(G93A) miceExperimental Neurology201: 120130 |

105 | Banks GT, Bros-Facer V, Williams HP, Chia R, Achilli F, Bryson JB, Greensmith L, Fisher EM(2009) Mutant glycyl-tRNA synthetase (Gars) ameliorates SOD1(G93A) motor neuron degeneration phenotype but has little affect on Loa dynein heavy chain mutant micePLoS One4: e6218 |

106 | Ebert S, Goos M, Rollwagen L, Baake D, Zech WD, Esselmann H, Wiltfang J, Mollenhauer B, Schliebs R, Gerber J, Nau R(2010) Recurrent systemic infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae do not aggravate the course of experimental neurodegenerative diseasesJ Neurosci Res88: 11241136 |

107 | Hashimoto K, Hayashi Y, Watabe K, Inuzuka T, Hozumi I(2011) Metallothionein-III prevents neuronal death and prolongs life span in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model miceNeuroscience189: 293298 |

108 | Feng X, Peng Y, Liu M, Cui L(2012) DL-3-n-butylphthalide extends survival by attenuating glial activation in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeuropharmacology62: 10041010 |

109 | Sharp PS, Akbar MT, Bouri S, Senda A, Joshi K, Chen HJ, Latchman DS, Wells DJ, de Belleroche J(2008) Protective effects of heat shock protein 27 in a model of ALS occur in the early stages of disease progressionNeurobiol Dis30: 4255 |

110 | Narai H, Manabe Y, Nagai M, Nagano I, Ohta Y, Murakami T, Takehisa Y, Kamiya T, Abe K(2009) Early detachment of neuromuscular junction proteins in ALS mice with SODG93A mutationNeurol Int1: e16 |

111 | Vaknin I, Kunis G, Miller O, Butovsky O, Bukshpan S, Beers DR, Henkel JS, Yoles E, Appel SH, Schwartz M(2011) Excess circulating alternatively activated myeloid (M2) cells accelerate ALS progression while inhibiting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitisPLoS One6: e26921 |

112 | Yoo YE, Ko CP(2011) Treatment with trichostatin A initiated after disease onset delays disease progression and increases survival in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisExp Neurol231: 147159 |

113 | Zhu YB, Sheng ZH(2011) Increased axonal mitochondrial mobility does not slow amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-like disease in mutant SOD1 miceJ Biol Chem286: 2343223440 |

114 | Ralph GS, Radcliffe PA, Day DM, Carthy JM, Leroux MA, Lee DC, Wong LF, Bilsland LG, Greensmith L, Kingsman SM, Mitrophanous KA, Mazarakis ND, Azzouz M(2005) Silencing mutant SOD1 using RNAi protects against neurodegeneration and extends survival in an ALS modelNat Med11: 429433 |

115 | Saito Y, Yokota T, Mitani T, Ito K, Anzai M, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Mizusawa H(2005) Transgenic small interfering RNA halts amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a mouse modelJ Biol Chem280: 4282642830 |

116 | Gould TW, Buss RR, Vinsant S, Prevette D, Sun W, Knudson CM, Milligan CE, Oppenheim RW(2006) Complete dissociation of motor neuron death from motor dysfunction by Bax deletion in a mouse model of ALSJ Neurosci26: 87748786 |

117 | Poesen K, Lambrechts D, Van Damme P, Dhondt J, Bender F, Frank N, Bogaert E, Claes B, Heylen L, Verheyen A, Raes K, Tjwa M, Eriksson U, Shibuya M, Nuydens R, Van Den Bosch L, Meert T, D’Hooge R, Sendtner M, Robberecht W, Carmeliet P(2008) Novel role for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1 and its ligand VEGF-B in motor neuron degenerationJ Neurosci28: 1045110459 |

118 | Turner BJ, Parkinson NJ, Davies KE, Talbot K(2009) Survival motor neuron deficiency enhances progression in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse modelNeurobiol Dis34: 511517 |

119 | Taes I, Goris A, Lemmens R, van Es MA, van den Berg LH, Chio A, Traynor BJ, Birve A, Andersen P, Slowik A, Tomik B, Brown RHJr, Shaw CE, Al-Chalabi A, Boonen S, Van Den Bosch L, Dubois B, Van Damme P, Robberecht W(2010) Tau levels do not influence human ALS or motor neuron degeneration in the SOD1G93A mouseNeurology74: 16871693 |

120 | Crosio C, Valle C, Casciati A, Iaccarino C, Carri MT(2011) Astroglial inhibition of NF-kappaB does not ameliorate disease onset and progression in a mouse model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)PLoS One6: e17187 |

121 | Finkelstein A, Kunis G, Seksenyan A, Ronen A, Berkutzki T, Azoulay D, Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Schwartz M(2011) Abnormal changes in NKT cells, the IGF-1 axis, and liver pathology in an animal model of ALSPLoS One6: e22374 |

122 | Keller AF, Gravel M, Kriz J(2011) Treatment with minocycline after disease onset alters astrocyte reactivity and increases microgliosis in SOD1 mutant miceExp Neurol228: 6979 |

123 | Bhattacharya A, Bokov A, Muller FL, Jernigan AL, Maslin K, Diaz V, Richardson A, Van Remmen H(2012) Dietary restriction but not rapamycin extends disease onset and survival of the H46R/H48Q mouse model of ALSNeurobiol Aging33: 18291832 |

124 | Perez-Garcia MJ, Burden SJ(2012) Increasing MuSK activity delays denervation and improves motor function in ALS miceCell Re2: 497502 |

125 | Ringer C, Weihe E, Schutz B(2012) Calcitonin gene-related peptide expression levels predict motor neuron vulnerability in the superoxide dismutase 1-G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurobiol Dis45: 547554 |

126 | Petri S, Kiaei M, Wille E, Calingasan NY, Flint Beal M(2006) Loss of Fas ligand-function improves survival in G93A-transgenic ALS miceJ Neurol Sci251: 4449 |

Figures and Tables

Fig.1

Representation of raw data from literature. The (A) mean onset, (C) mean survival, (E), mean disease duration for each independent group of mice was plotted with a size proportional to the sample size of that group. Data was stratified by both the sex of the group and genetic background strain. The (B) mean onset, (D) mean survival, and (F) mean disease duration were aggregated across groups and the distributions weighted by group sample size and results accumulated in histograms.

Fig.2

The effect of G93A mouse genetic background strain and sex on the age at disease onset. (A) Linear regression was performed with the mean age at onset for each group modeled as the response with mouse sex and genetic background factored as categorical predictors with full interaction. Data represents the predicted response ± SEM computed at values of the interaction term corresponding to each category. Observations were weighted on the basis of sample size. *p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction. (B) The time until onset was modeled as Cox proportional hazards with mouse sex and genetic background factored as categorical predictors with full interaction. Data represents the survival curve for onset predicted by the Cox model for combinations of categorical predictors. Observations were weighted as frequencies given by the group sample size.

Fig.3

The variation in onset times by onset determination criteria and genetic background strain. Linear regression was performed with the mean age at onset for each group modeled as the response and the onset definition category and genetic background factored as categorical predictors with full interaction. Data represents the predicted response ± SEM computed at values of the categorical interaction term corresponding to each category. Observations were weighted on the basis of sample size. *p < 0.05 for the comparison between the marked column and the “General” group within the strain.

Fig.4

The effect of G93A mouse genetic background strain and sex on the age at death. (A) Linear regression was performed with the mean age at death for each group modeled as the response with mouse sex and genetic background factored as categorical predictors and onset included as a continuous predictor with full interaction between the terms. Data represents the predicted response ± SEM computed at values of the categorical interaction term corresponding to each category at the group-specific mean onset. Observations were weighted on the basis of sample size. *p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction. (B) The age at death was modeled as Cox proportional hazards with mouse sex and genetic background factored as categorical predictors with full interaction. Onset was included as an independent continuous predictor. Data represents the survival curve predicted by the Cox model for combinations of categorical predictors. Observations were weighted as frequencies given by the group sample size.

Fig.5

The effect of G93A mouse genetic background strain and sex on the duration of disease. (A) Linear regression was performed with the disease duration for each group modeled as the response with mouse sex and genetic background factored as categorical predictors and onset included as a continuous predictor with full interaction between the terms. Data represents the predicted response ± SEM computed at values of the categorical interaction term corresponding to each category at the group-specific mean onset. Observations were weighted on the basis of sample size. *p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction. (B) The disease duration was modeled as Cox proportional hazards with mouse sex and genetic background factored as categorical predictors with full interaction. Onset was included as an independent continuous predictor. Data represents the survival curve predicted by the Cox model for combinations of categorical predictors. Observations were weighted as frequencies given by the group sample size.

Table 1

Data source and sample information

| Category | Articles | Groups | Mice | References |

| B6SJL, Female | 15 | 17 | 203 | [11, 47, 56, 61–72] |

| B6SJL, Male | 14 | 16 | 192 | [11, 47, 56, 61, 62, 67, 69, 70, 72–77] |

| B6SJL, Mixed | 43 | 58 | 909 | [2–16, 46, 49, 71, 78–102] |

| C57BL/6, Female | 9 | 11 | 173 | [25, 44, 45, 103–108] |

| C57BL/6, Male | 14 | 21 | 294 | [22, 25, 44, 45, 50, 57, 58, 104, 105, 109–113] |

| C57BL/6, Mixed | 22 | 27 | 472 | [17–20, 22, 23, 25, 45, 48, 104, 114–125] |

| B6SJL, General/Other | 30 | 45 | 628 | [3–5, 10, 11, 13–16, 61, 66–69, 71, 73–79, 82, 84, 85, 87, 88, 95, 98, 99] |

| B6SJL, Hindlimb Tremor | 5 | 9 | 163 | [46, 70, 72, 92, 94] |

| B6SJL, Non-Hindlimb Tremor | 6 | 8 | 171 | [7, 56, 62, 81, 91, 102] |

| B6SJL, Rotarod Decline | 20 | 29 | 342 | [2, 8, 9, 12, 47, 49, 63–65, 80, 83, 86, 89, 90, 93, 96, 97, 100, 101, 126] |

| C57BL/6, General/Other | 16 | 26 | 358 | [19–21, 45, 48, 50, 104–106, 109, 113, 115, 118–120, 123] |

| C57BL/6, Hindlimb Tremor | 3 | 8 | 93 | [57, 58, 108] |

| C57BL/6, Non-Hindlimb Tremor | 3 | 6 | 153 | [17, 25, 110] |

| C57BL/6, Rotarod Decline | 14 | 19 | 335 | [18, 22, 23, 44, 103, 107, 111, 112, 114, 116, 117, 121, 122, 124] |

Number of articles, independent groups, and mice that relate to each category of interest. Categories are named first by the genetic background strain followed by either a sex group label or a label for the onset determination category. Articles may be counted in multiple categories if that article contains information for multiple groups.