A Critical Assessment of Research on Neurotransmitters in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

The purpose of this mini-forum, “Neurotransmitters and Alzheimer’s Disease”, is to critically assess the current status of neurotransmitters in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotransmitters are essential neurochemicals that maintain synaptic and cognitive functions in mammals, including humans, by sending signals across pre- to post-synaptic neurons. Authorities in the fields of synapses and neurotransmitters of Alzheimer’s disease summarize the current status of basic biology of synapses and neurotransmitters, and also update the current status of clinical trials of neurotransmitters in Alzheimer’s disease. This article discusses the prevalence, economic impact, and stages of Alzheimer’s dementia in humans.

INTRODUCTION

In 1906, the German physician Alois Alzheimer, a pioneer in linking symptoms of disease to microscopic brain changes, described the case of Auguste D., a patient who had profound memory loss, unfounded suspicions about her family, and other psychological changes. After her death, in an autopsy, Dr. Alzheimer found dramatic brain shrinkage and abnormal deposits of protein in and around nerve cells in her brain [1]. In 1910, from his efforts in identifying hallmark pathological changes in his patients’ brains, Dr. Alzheimer was bestowed the honor of having Alzheimer’s disease (AD) named after him [1]. By 1984, through biochemical analytical methods, amyloid-β (Aβ), a major pathological hallmark of AD, was identified by Drs. George Glenner and Caine Wong [2]. Just two years later in 1986, Montejo de Garcini and colleagues identified the cytoskeletal protein tau and its phosphorylated form as additional hallmark features of AD [3, 4].

The condition that Dr. Alzheimer first described in Auguste D appears to be AD-related dementia due to the presence of presenilin 1 mutation, which involves memory loss and the loss of other intellectual abilities that are serious enough to interfere with activities of daily living. According to the Center for DiseaseControl, AD is a common cause of dementia that affects as many as 50 to 70% of persons diagnosed with AD. Scientists have found that persons with mild cognitive impairment have an increased risk of developing AD or another dementia.

AD occurs in both early-onset familial and late-onset sporadic forms. Early-onset familial AD affects persons less than 65 years of age. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that in the United States, up to 5% of all persons diagnosed with AD have early-onset familial AD. The World Alzheimer’s Report has reported that, in 2016, over 46.8 million people worldwide had one of the forms of AD, and it projects that this number will increase to more than 131 million by 2050. Also according to the World Alzheimer’s Report, the total estimated annual worldwide health care costs for persons with AD was $818 billion in 2016, and by 2018, AD will become a trillion-dollar disease [5].

Multiple brain sites are affected by AD, including the entorhinal cortex, the temporal cortex, the fronto-parietal cortex, the hippocampus, and the subcortical nuclei [6]. It is in these sites that synaptic loss, synaptic damage, and mitochondrial abnormalities and dysfunction are early events in AD pathogenesis. Major pathological and cellular changes in these brain sites include the formation and accumulation of Aβ and Aβ plaques, and hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofibrillary tangles [7–11]. Loss of synapses and synaptic damage in the brain sites affected by AD are the best correlates of cognitive decline in patients diagnosed with AD [10].

In the early stage of AD, a person may function independently and may still drive, work, and participate in social activities. However, common difficulties early in AD progression include: memory lapses, such as forgetting familiar words and names, and the location of everyday objects having difficulty in performing common tasks at work or at home; forgetting what was just read; losing or misplacing valuable objects; and experiencing problems when trying to plan or organize schedules or physical spaces.

The middle stage of AD progression can last for many years. In the middle stage of AD, persons may exhibit symptoms that become increasingly noticeable to others, such as being excessively moody or withdrawn; being unable to recall their own address or telephone number, or the high school or college from which they graduated; needing assistance in choosing proper clothing for the season or an occasion; and becoming lost or spatially disoriented. Other changes include being suspicious or delusional, and performing repetitive behaviors, like hand-wringing or tissue-shredding.

In the final stage of AD progression, persons cannot adequately respond to their environment, and their memory and cognitive skills continue to worsen. They can no longer carry on a logical conversation or track topics in conversations, and they cannot articulate sentences that reflect what is happening in their immediate vicinity. They have increasing difficulty controlling movements of their fingers, hands, and feet, and their physical abilities to walk, sit, and swallow deteriorate. They become vulnerable to infections, especially pneumonia. They also need assistance with daily activities, such as dressing and bathing. Their memory and cognitive skills also deteriorate, and they typically continue to experience personality changes, such as being more susceptible to temper tantrums and fits of laughing.

According to 2016 statistics from the Alzheimer’s Association, two-thirds of women and one-third of men are at lifetime risk for developing AD. Studies of AD mouse models have found this risk is related to increased levels of Aβ in the brains of mice, and a few studies of postmortem brains from persons with AD have found that female brains have increased levels of Aβ [12]. However, even with women being at greater risk of developing AD, very little research has focused on women with AD. Most research has focused on males (mouse or human). The NIH and other funding agencies worldwide are now trying to rectify this problem through initiatives requiring the study of both males and females with AD. Researchers are currently investigating whether menopause-related hormonal changes play a role in the higher levels of Aβ found in the brains of women with AD. Neurotransmitter levels are also altered in women compared to men, as are depression, anxiety, and co-morbidity rates [13]. It is critically important that AD research includes much higher rates of female participants.

AD is a multifactorial disease, caused by mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1, and presenilin 2 genes, and DNA variants in the sortilin-related receptor 1, clusterin, complement component receptor 1, and particular genes, including CD2AP, CD33, EPHA1, and MS4A4/MS4A6E. Aging is the number one risk factor for both early- and late-onset AD. The ApoE 4/4 genotype is a major contributor tolate-onset AD, but other major contributors to late-onset AD are still unknown [14]. Type 2 diabetes, traumatic brain injury, and stroke are also contributors to late-onset AD [15]. In addition, Down syndrome is associated with AD. Lifestyle activities, including diet and environmental and occupational exposures to chemicals, are other contributing factors impacting the pathogenesis of late-onset AD, but the extent of contribution is not known.

Recent research has found that some risk factors for AD are modifiable, and others are not. Non-modifying risk factors associated with the AD disease process include age, sex, changes in the individual genome, and mutations in the genes APP, PS1, and PS2. Modifying risk factors include health conditions impacted by lifestyle activities, such as smoking, low income, physical inactivity, and low intake of foods having omega-3 fatty acids. Modifying health conditions include diabetes, obesity, hypertension, high blood pressure, depression, high cholesterol, and high blood homocysteine.

The purpose of this special issue is to assess recent developments in neurotransmitter research in relation to AD. Authorities in the fields of AD, aging, neurotransmitters, synapses, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction have summarized recent advancements in the field of AD. Summaries of individual articles are given below.

CURRENT STATUS OF NEUROTRANSMITTERS AND ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

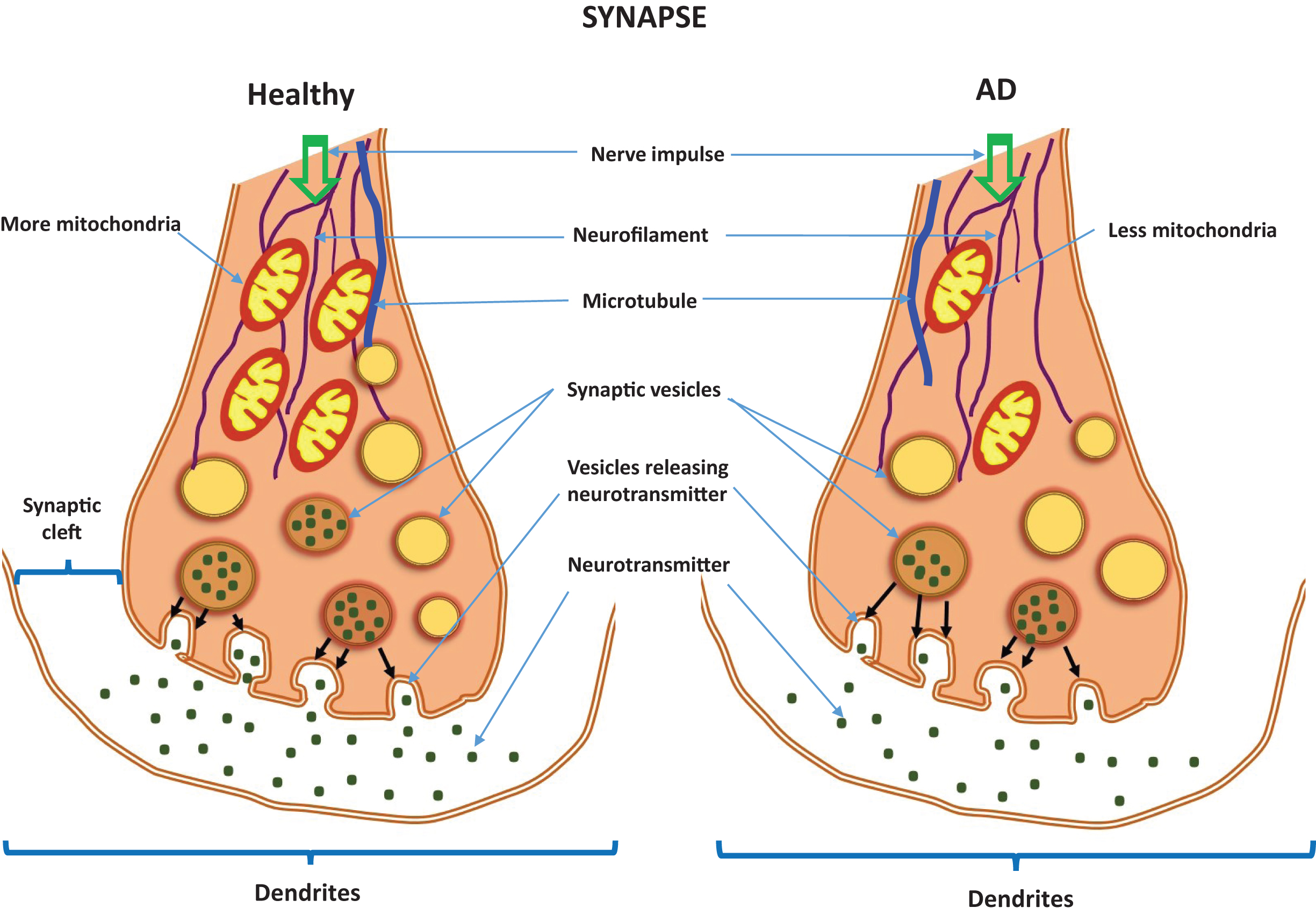

Neurotransmitters play a large role in maintaining synaptic and cognitive functions in mammals, including humans, by sending signals across synapses [16]. Neurotransmitters are usually stored in synaptic vesicles, beneath the membrane in the axon terminal, and are released into the synapse with the appropriate signal from neurons. The released neurotransmitters establish connections through the synaptic cleft and bind to their appropriate receptors.

Neurotransmitters with a known role in AD pathogenesis include acetylcholine, which is synthesized from serine; dopamine, from L-phenyl alanine/L-tyrosine; GABA, from glutamate, a by-product of decarboxylation; serotonin, from L-tryptophan; histaminergic, from L-histidine; and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), from D-aspartic acid and arginine. Neurotransmitters without a significant role in AD pathogenesis include glutamate, glycine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, melatonin, gastrin, oxytocin, vasopressin, cholecystokinin, neuropeptide Y, and enkephalins. However, these neurotransmitters may have a role in causing oxidative stress, which is known to be involved in AD pathogenesis.

Metabotropic and ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors are localized to the postsynaptic membrane. Metabotropic receptors are membrane receptors that act through a secondary messenger, whereas ionotropic receptors are ligand-gated channels (Fig. 1). Included in the group of metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors are acetylcholine receptors (AChRs): muscarinic AChRs are receptors for histamine; GABAB AChRs are receptors for GABA adenosine AChRs, for adenosine; serotonin receptors, G-protein coupled receptors, are for serotonin, and a group of ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors (nicotinic AChRs, GABAA &A - ρ receptors also for GABA, and additionally 5-HT). These are the major therapeutic targets for AD prevention.

Fig.1

Neurotransmitters in a healthy synapse and an Alzheimer’s disease synapse.

Ravi Rajmohan and P. Hemachandra Reddy discuss the involvement of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau in neurotransmitter pathology, in AD [17]. They cover biochemical, cellular, molecular, and pathological studies of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau accumulation in AD neurons, and how Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau lesions directly damage synapses and alter neurotransmission. In vitro evidence suggests that Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau have direct and indirect cytotoxic effects on neurotransmission, axonal transport, signaling cascades, organelle function, and immune response, in ways that lead to synaptic loss and to dysfunction in neurotransmitter release. They conclude that removal of accumulations of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau may reduce the severity of AD symptoms.

Cynthia L. Bethea and colleagues discuss the role of the neurotransmitter serotonin in altering the mood and anxiety levels of persons with overt symptoms of AD [13]. They review recent literature on AD, depression, and serotonin. They present research that points to a link between increased depression in women and a higher prevalence of AD. They discuss serotonin neuron viability in AD progression, the involvement of the caspase-independent pathway, and apoptosis-inducing factors in serotonin-neuron viability, as well as gene expression related to neurodegeneration and neuron viability in AD progression, in adult and aged menopausal macaques. Their article focuses on ovarian steroids, particularly estrogen, which are crucial for the production of serotonin and for neuronal health.

Saurabh Kumar Jha and colleagues discuss stress-induced synaptic dysfunction and neurotransmitter release in AD [18]. They emphasize that communication between neurons at synaptic junctions is an elegant process that facilitates the transmission of various electro-chemical signals in the central nervous system. They discuss mechanisms associated with the alteration of signal transmission across synapses in the neocortex and hippocampus— alterations that lead to insidious cognitive and memory decline in AD. They also provide compelling evidence that soluble Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau are toxins involved in aberrant neurotransmitter release at synapses involved in cognitive decline seen in AD.

Rui Wang and P. Hemachandra Reddy discuss the role of glutamate and NMDA receptors (NMDAR) in AD [19]. Excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission via NMDAR is critical for synaptic plasticity and survival of neurons. However, cell death and excitotoxicity are caused by excessive NMDAR activity; thus, excessive NMDAR may be an underlying mechanism of neurodegeneration in AD. Studies indicate that NMDAR-mediated responses are induced by regionalized receptor activities, followed by different downstream signaling pathways. They report that excessive, extra-synaptic NMDAR activity can be selectively blocked by the drug memantine, an NMDAR antagonist [19].

Ramesh Kandimalla and P. Hemachandra Reddy update research into therapeutics of neurotransmitters in AD pathogenesis and progression [20]. They assess the latest developments in neurotransmitter research that use cell and mouse models of AD. They also review clinical trials studying the impact of neurotransmitter agonists and antagonists in persons with AD. They report on cellular changes that are involved with the AD disease process, including synaptic damage, mitochondrial abnormalities, and inflammatory responses in AD brains exhibiting Aβ accumulation and hyperphosphorylated tau [20].

Lan Guo and colleagues discuss the association between mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic transmission deficits in AD [21]. Impaired mitochondrial energy production, deregulated mitochondrial calcium handling, and excess mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and release play important roles in mediating the deregulation of synaptic transmission in AD. They also explain mechanisms by which synapses are injured in particular AD-related conditions. They suggest that a better understanding of mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic stress in AD may lead to therapeutic strategies that target mitochondrial deficits and that protect synaptic transmission known to be affected in AD [21].

Qian Cai and Prasad Tammineni discuss mitochondrial aspects of synaptic dysfunction in AD. Synaptic damage, an early pathological event in AD, correlates strongly with increased cognitive deficits and memory loss [22]. Mitochondria are essential organelles that supply the nucleuotide adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for several synaptic functions. Neurons utilize specialized mechanisms in which mitochondria buffer Ca2 + and serve as local energy sources by supplying ATP to sustain neurotransmitter release. When this supply is interrupted by mitochondrial alterations caused by Aβ accumulation and hyperphosphorylated tau, synapses do not receive ATP and thus cannot function. This mechanism suggests that mitochondria are the promising targets of new therapeutics inAD [22].

Eric Tönnies and Eugenia Trushina research the role of oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction in AD [23]. In AD-affected brain regions, the loss of synapses correlates the strongest with cognitive impairment and has been identified as an early precursor to neuronal loss. Oxidative stress has also been recognized as a contributing factor to AD progression. Increased production of ROS is associated with age- and AD-dependent losses of mitochondrial function, altered metal homeostasis, and reduced antioxidant defenses, events that in turn directly affect synaptic activity and neurotransmission in neurons and that lead to AD-related cognitive dysfunction. They also focus on molecular targets affected by ROS, including nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, lipids, proteins, calcium homeostasis, mitochondrial dynamics and function, cellular architecture, receptor trafficking and endocytosis, and energyhomeostasis [23].

Shanya Jiang and Kiran Bhaskar address the pathological hallmarks of complementary cytokine and chemokine systems that regulate synaptic function and dysfunction in AD [24]. They report on Aβ accumulation and hyperphosphorylated tau tangles, neuroinflammation, and synaptic and neuronal loss in AD brains from persons with memory loss and cognitive impairment. They report on recent genetic evidence suggesting that the neurotransmitters may link altered immune pathways and synaptic dysfunction in AD. These researchers suggest that immune system-mediated synaptic pruning may initiate AD pathogenesis. They also discuss the importance of crosstalk among neurons, microglia, and astrocytes in the regulation of synaptic functioning in persons with AD [24].

Eric B. Gonzales and Nathalie Sumien discuss the role of acidity and acid-sensing ion channels in normal neurons and in neurons from AD-affected brain regions [25]. A potential avenue of research for new therapies to reduce AD symptoms are protons and their associated receptors in acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs). ASICs play a crucial role in maintaining proper cognitive function and are associated with levels of acidity in the AD brain [25].

IMPORTANT QUESTIONS ABOUT NEUROTRANSMITTERS IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Researchers in AD field are seeking answers to several AD-related questions, including:

1) Do we need more research on neurotransmitter serotonin involved in depression, anxiety and comorbidity in AD?

2) Is there a relationship between neurotransmitters and the amyloid hypothesis, which states that, in AD, oligomeric Aβ is the toxic form responsible for synaptic damage?

3) Also, mitochondrial ATP is essential at synapses, which is where oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction inhibit ATP; to better understand the AD disease process, do we need more research on the relationship between synapses and mitochondria?

4) Do we need more research on neuron-glia and neuron-astrocyte cross-talk in AD neurons in relation to neurotransmitters?

5) Do problems in neurotransmitter function actually impact the pathogenesis of AD?

This mini-forum in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease focuses on the relationship between neurotransmitters and AD. It provides timely resources for students, scholars, clinicians, and basic science researchers who are seeking a basic understanding of neurotransmitters in AD.

Thank you to all of our contributors for their outstanding articles and to our reviewers who provided cogent evaluations of our articles. Special recognition is given to Beth Kumar, Managing Editor of this issue; George Perry, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease; Rasjel van der Holst, publisher at IOS Press; and all of the IOS Press production and printing staff for their professional support.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work presented in this article is supported by the NIH grants AG042178 and AG047812, and the Garrison Family Foundation.

REFERENCES

[1] | Toodayan N ((2016) ) Professor Alois Alzheimer (1864-1915): Lest we forget. J Clin Neurosci 31: , 47–55. |

[2] | Glenner GG , Wong CW ((1984) ) Alzheimer’s disease: Initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 425: , 534–539. |

[3] | Montejo de Garcini E , Serrano L , Avila J ((1986) ) Self assembly of microtubule associated protein tau into filaments rebling those found in Alzheimer disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 141: , 790–796. |

[4] | Avila J ((2006) ) Tau protein, the main component of paired helical filaments. J Alzheimers Dis 9: , 171–175. |

[5] | Alzheimer’s Disease International. ((2016) ) World Alzheimer Report. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2016.pdf |

[6] | Reddy PH , McWeeney S ((2006) ) Mapping cellular transcriptosomes in autopsied Alzheimer’s disease subjects and relevant animal models. Neurobiol Aging 27: , 1060–1077. |

[7] | Mattson MP ((2004) ) Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 430: , 631–639. |

[8] | LaFerla FM , Green KN , Oddo S ((2007) ) Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: , 499–509. |

[9] | Reddy PH , Manczak M , Mao P , Calkins MJ , Reddy AP , Shirendeb U ((2010) ) Amyloid-beta and mitochondria in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for synaptic damage and cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis 20: (Suppl 2), S499–S512. |

[10] | Reddy PH , Tripathi R , Troung Q , Tirumala K , Reddy TP , Anekonda V , Shirendeb UP , Calkins MJ , Reddy AP , Mao P , Manczak M ((2012) ) Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic degeneration as early events in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications to mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822: , 639–649. |

[11] | Selkoe DJ , Hardy J ((2016) ) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 8: , 595–608. |

[12] | Alzheimer’s Association ((2016) ) Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Available from: http://www.alz.org/facts/overview.asp |

[13] | Bethea CL , Reddy AP , Christian FL ((2017) ) How studies of the serotonin system in macaque models of menopause relate to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1001–1015. |

[14] | Mao P , Reddy PH ((2011) ) Aging and amyloid beta-induced oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for early intervention and therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: , 1359–1370. |

[15] | Vijayan M , Reddy PH ((2016) ) Stroke, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: Molecular links. J Alzheimers Dis 54: , 427–443. |

[16] | Soreq H ((2015) ) Checks and balances on cholinergic signaling in brain and body function. Trends Neurosci 38: , 448–458. |

[17] | Rajmohan R , Reddy PH ((2017) ) Amyloid-beta and phosphorylated tau accumulations cause abnormalities at synapses of Alzheimer’s disease neurons. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 975–999. |

[18] | Jha SK , Jha NK , Kumar D , Sharma R , Shrivastava A , Ambasta RK , Kumar P ((2017) ) Stress-induced synaptic dysfunction and neurotransmitter release in Alzheimer’s disease: Can neurotransmitters and neuromodulators be potential therapeutic targets? J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1017–1039. |

[19] | Wang R , Reddy PH ((2017) ) Role of glutamate and NMDA receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1041–1048. |

[20] | Kandimalla R , Reddy PH ((2017) ) Therapeutics of neurotransmitters in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1049–1069. |

[21] | Guo L , Tian J , Du H ((2017) ) Mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic transmission failure in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1071–1086. |

[22] | Cai Q , Tammineni P ((2017) ) Mitochondrial aspects of synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1087–1103. |

[23] | Tönnies E , Trushina E ((2017) ) Oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1087–1103. |

[24] | Jiang S , Bhaskar K ((2017) ) Dynamics of the complement, cytokine, and chemokine systems in the regulation of synaptic function and dysfunction relevant to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1123–1135. |

[25] | Gonzales EB , Sumien N ((2017) ) Acidity and acid-sensing ion channels in the normal and Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Alzheimers Dis 57: , 1137–1144. |